New results from People for Education’s 2023-24 Annual Ontario School Survey show that ongoing staff shortages and increased student needs are having an adverse impact on special education in Ontario schools.

New results from People for Education’s 2023-24 Annual Ontario School Survey show that ongoing staff shortages and increased student needs are having an adverse impact on special education in Ontario schools.

The data are based on responses from 1,030 of Ontario’s publicly funded schools, representing all regions of the province and 70 of Ontario’s 72 school boards.

In Ontario, special education support is offered to students who have a wide range of needs—including, but not limited to, identified learning disabilities, mild struggles in some areas of learning, giftedness, behavioural challenges, and physical exceptionalities. While some students with special education needs require a great deal of support and/or accommodations, others simply need a little day-to-day support from their classroom teacher.

Special education programs and services help to ensure that all students benefit fully from their school experience. For many students, having some special education support early-on can mean they are less likely to require support in later grades.

In 2023-24:

-

100% of elementary schools and 99% of secondary schools have at least some students receiving special education assistance.

-

On average per school, 16% of elementary and 28% of secondary students receive some form of special education support, a proportion that has remained relatively steady over the last decade.

-

94% of elementary schools and 95% of secondary schools have a special education teacher, either full or part-time–this is a decline since 2019/20, when 100% of elementary and 98% of secondary schools reported having special education teachers.

-

On average, the ratio of special education students to special education teachers is 39 to 1 in elementary schools, and 85 to 1 in secondary schools, numbers that have remained fairly stable over the last five years.

-

84% of elementary and 79% of secondary schools have at least one full-time educational assistant. For elementary schools, this has been a steady decline since 2019/20 when 89% of elementary schools had at least one full-time educational assistant.

“Lack of support staff [means] staff who are at school are under extra stress. They are spread too thin.”

Elementary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

In their responses to the survey, many principals commented that daily staff shortages mean that special education teachers must often step in to replace classroom teachers and educational assistants. Nearly half of elementary (42%) and secondary (46%) schools report experiencing shortages of educational assistants every day.

“There are not enough SERTS [special education resource teachers] or EA’s [educational assistants] in the system. And if they are sick, neither position is ever filled by a qualified staff.”

Elementary school principal, Central Ontario

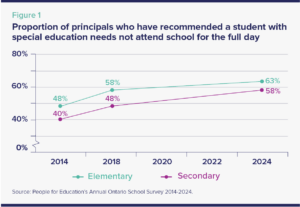

A lack of appropriate staff and support can also result in requests to keep students at home. Periodically over the last ten years, we have asked principals if they have ever had to request that parents keep their child with special education needs home for the day.

The proportion of principals saying yes has increased steadily–from 48% of elementary principals in 2013-14, to 63% in 2023-24. In secondary schools, that number has risen from 40% in 2013-14 to 58% this year.

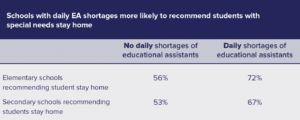

The results were exacerbated by staff shortages: Principals who reported their schools had daily EA shortages were much more likely to report that they have had to recommend students stay home.

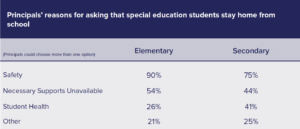

Principals are most likely to name safety issues and a lack of necessary support as the reasons that they are forced to make this request.

“More EAs are needed. Our SERT team is acting as EAs most of the day and cannot get to special education for those who are struggling academically.”

Elementary school principal, GTA

Elementary schools in neighbourhoods with low median family incomes have, on average, a higher proportion of students receiving special education support. In these schools, an average of 20% of students are receiving special education support, compared to 14% of students in high income schools. On the other hand, schools in lower-income neighbourhoods were more likely to provide tutoring programs and de-streaming resources for parents/guardians.

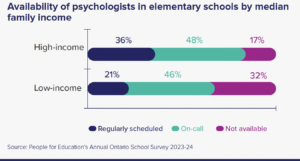

Low-income elementary schools are much less likely to report they have access to psychologists, either regularly scheduled or on-call. This may be partly due to the differences in school size: on average, low-income elementary schools have 302 students each compared to 454 in high-income elementary schools. At the same time, low-income schools have more than double the proportion of students waiting for assessments.

Assessments are important because once a student is assessed and identified with a special education exceptionality, they have a right to a range of special education supports.

While elementary schools in low-income neighbourhoods are less likely to have access to psychologists, they are also much less likely than schools in high-income neighbourhoods (75% vs 92%) to report that at least some families are having their children assessed privately. The costs for private psycho-educational assessments can be as high as $3,000–but once students are assessed and have an identification from the assessment, they can skip the waiting list for services.

On the other hand, elementary schools in low-income neighbourhoods are more likely to provide Individual Education Plans for students waiting for assessment than schools in high-income neighbourhoods (90% vs. 74%). Low-income elementary schools are also more likely to provide special education supports to students who have not yet been identified (94% vs 84%).

“The waiting lists for programs and community supports is too long, so students are not receiving services in a timely manner. There are too few Board Psychologists and the few that we do have are being asked to attend far too many meetings, rather than working to clear the backlog of students that need to be assessed.”

Elementary school principal, Central Ontario

The majority of elementary and secondary schools have students waiting to be assessed to determine whether they have special education needs.

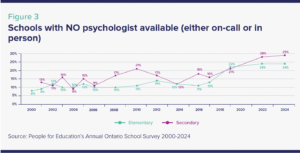

Assessments are, for the most part, delivered by school psychologists, but in 2023-24, only 26% of elementary schools reported they had regularly scheduled access to psychologists, an all-time low since we have been reporting on this number. The percentage of elementary schools reporting they have no access to psychologists has increased fairly steadily from 13% in 2016-17 to 24% in 2023-24.

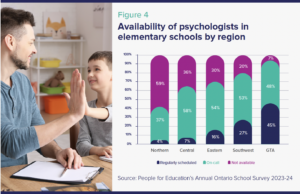

There are significant regional differences in schools’ access to these professionals. Schools in the GTA are much more likely to have access to psychologists either regularly scheduled or on-call, whereas schools in Northern Ontario are more likely to report having no access at all.

Principals have consistently pointed to challenges in providing effective special education supports for their students. For this reason, People for Education continues to recommend that the province convene an Education Task Force–including representatives from teacher, principal, and education support staff associations, school board administrators, faculties of education, special education organizations, provincial policymakers, and students–to provide input on government policy before it is implemented, and to help design new policy and funding models to address a range of issues including staff shortages, and effective and equitable design for special education supports and programs.

Findings from this report are based on 1,030 responses to People for Education’s 2023-24 Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS) collected from principals across 70 of Ontario’s 72 publicly funded school boards. This represents 21% of the publicly funded schools in the province.

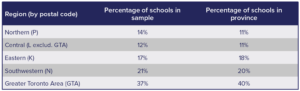

Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and quoted material in this report originate from People for Education’s 2023-24 AOSS, the 27th annual survey of elementary schools, and the 23rd annual survey of secondary schools in Ontario. Surveys from the 2023-24 AOSS were completed online via SurveyMonkey in both English and French in the fall of 2023. Survey responses were disaggregated to examine survey representation across provincial regions (see table below). Schools were sorted into geographical regions based on the first letter of their postal code. The GTA region includes schools with M postal codes as well as those with L postal codes located in GTA municipalities.

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using inductive analysis. Researchers read responses and coded emergent themes in each set of data (i.e., the responses to each of the survey’s open-ended questions). The quantitative analyses in this report are based on descriptive statistics. The primary objective of the descriptive analyses is to present numerical information in a format that is accessible to a broad public readership. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. All calculations have been rounded to the nearest whole number and may not total 100% in displays of disaggregated categories. All survey responses and data are kept confidential and stored in conjunction with TriCouncil recommendations for the safeguarding of data. For questions about the methodology used in this report, please contact the research team at PFE: [email protected].