Over the past few years, Ontario has taken significant steps toward improving education for Indigenous students and engaging all students in learning about the cultures, experiences, and perspectives of Indigenous peoples. But there is still much work to be done.

Over the past few years, Ontario has taken significant steps toward improving education for Indigenous students and engaging all students in learning about the cultures, experiences, and perspectives of Indigenous peoples. But there is still much work to be done.

In terms of Indigenous education, there are two gaps in Ontario’s education system. One is the achievement gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. The second is the knowledge gap that permeates the system—the lack of knowledge about the history, cultures, and perspec-tives of Indigenous peoples in Canada.1 In order to close these gaps, we need targeted programs, resources and professional development. All students will benefit from a deeper understanding of Canada’s history of colonization and its influence on current relationships between Indig-enous and non-Indigenous people.2

In this report, we examine the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, new data from People for Education’s 2015/16 Annual School Survey as it relates to Ontario’s provincial Indigenous Education Policy, and a recently released paper from Dr. Pamela Toulouse outlining the benefits of an Indigenous approach to education and the importance of broader goals for our public education system. Together, these three perspectives begin to articulate a possible way forward that will engender real change for all students.

With the rich number of local First Nations and a willingness to interact with our schools, we are blessed to have…support and opportunities for staff and students to be immersed in FNMI culture, historical and spiritual learning, and to celebrate and foster knowledge-building and ways to address and continue to learn and implement the Ministry of Education FNMI goals and programming.

Elementary school, Peterborough,

Victoria & Northumberland CDSB

THE CALLS TO ACTION

We are governed in our approach to reconciliation with this thought: the way that we have all been educated in this country…has brought us to where we are today—to a point where the psychological and emotional well-being of Aboriginal children has been harmed, and the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people has been seriously damaged… but education holds the key to making things better… if we agree on the objective of reconciliation, and agree to work together, the work we do today, will immeasurably strengthen the social fabric of Canada tomorrow.3

The Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair

Chair, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) was established in 2009 to examine the impact of Canada’s Indian Residential School system, and bear witness to the stories of survivors and those affected by these schools. The Commission released its final report in December, 2015.

In this landmark report, the TRC included several ‘Calls to Action’ related to education.4 If implemented, these actions will help to close both the achievement gap and the knowl-edge gap identified above, an essential part of the reconcilia-tion process.

According to Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the TRC, educa-tion provides one of the greatest hopes for repairing cultural attitudes, redressing the legacy of Indian Residential Schools, and advancing the process of reconciliation.

The Calls to Action specifically related to ‘education for reconciliation’ include:

- Make age-appropriate curriculum on residen-tial schools, Treaties, and Indigenous peoples’ historical and contemporary contributions to Canada a mandatory education requirement for kindergarten to grade 12 students.

- Provide the necessary funding to post-secondary institutions to educate teachers on how to integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms.

- Establish senior-level positions in government, at the Assistant Deputy Minister level or higher, dedicated to Indigenous content in education.

The TRC also calls for the Council of Ministers of Education of Canada to maintain an annual commitment to Indigenous education issues, including:

- Developing and implementing kindergarten to grade 12 curriculum and learning resources on Indigenous peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools.

- Sharing information and best practices on teaching curriculum related to residential schools and Indigenous history.

- Building student capacity for intercultural under-standing, empathy, and mutual respect.

- Identifying teacher-training needs relating to the above.5

MOVING TOWARD RECONCILIATION: WHAT’S HAPPENING IN ONTARIO’S PUBLIC SCHOOLS

The overriding issues affecting Indigenous student achievement are a lack of awareness among teachers of the particular learning styles of Indigenous stu-dents, and a lack of understanding within schools and school boards of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit cultures, histories, and perspectives…It is essential that First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students are engaged and feel welcome in school, and that they see themselves and their cultures in the curriculum and the school community.6

In 2007, Ontario’s Ministry of Education introduced its First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework, which identifies specific goals aimed at closing both the achieve-ment gap for Indigenous students and the knowledge gap experienced by all students. In the framework, 2016 was set as the target date for achieving these goals.7

Since 2014, People for Education has been surveying Ontar-io’s schools to find out about Indigenous education pro-grams, resources and challenges. While the public attention focused on First Nations education on reserves is under-standable, it is less well-known that in Ontario, as in most provinces, the vast majority (82%) of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit students attend provincially-funded schools.8

The First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Frame-work has led to some progress, but data from People for Education’s 2016 Annual School Survey and from Ontario’s

Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) show that the Ministry’s goals are unlikely to be achieved within the established timeline. The last available data from the EQAO (2011/12) shows a gap of more than 20 percentage points on reading, writing and math test scores between First Nations students and all students in English language school boards.9 While People for Education’s data show some improvements, there are still significant gaps in areas such as professional development for teachers and resources for schools with high proportions of Indigenous students.

IMPLEMENTING THE FIRST NATION, MÉTIS, AND INUIT POLICY FRAMEWORK: PEOPLE FOR EDUCATION ANNUAL SCHOOL SURVEY RESULTS SHOW PROGRESS

In 2014, the Ministry of Education introduced an Implemen-tation Plan for the First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework.10 The plan includes strategies and initia-tives to be undertaken by the Ministry and school boards with several identified goals, including:

- improved achievement and graduation rates for Indigenous students;

- increased number of Indigenous teaching and non-teaching staff;

- increased participation of Indigenous parents in their children’s education; and

- integration of educational opportunities so that all children and educators have increased knowledge about the cultures, traditions, and perspectives of Indigenous peoples.

Education provides one of the greatest hopes for repairing cultural attitudes, redressing the legacy of Indian Residential Schools, and advancing the process of reconciliation.

Justice Murray Sinclair,

Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Over the past several years, the province and school boards have been working to integrate Indigenous perspectives and knowledge throughout the K-12 curriculum, making progress toward the TRC’s Call to Action regarding mandatory cur-riculum.11 People for Education’s 2016 survey results show that Ontario schools have made some important gains in providing Indigenous education opportunities.

In 2016:

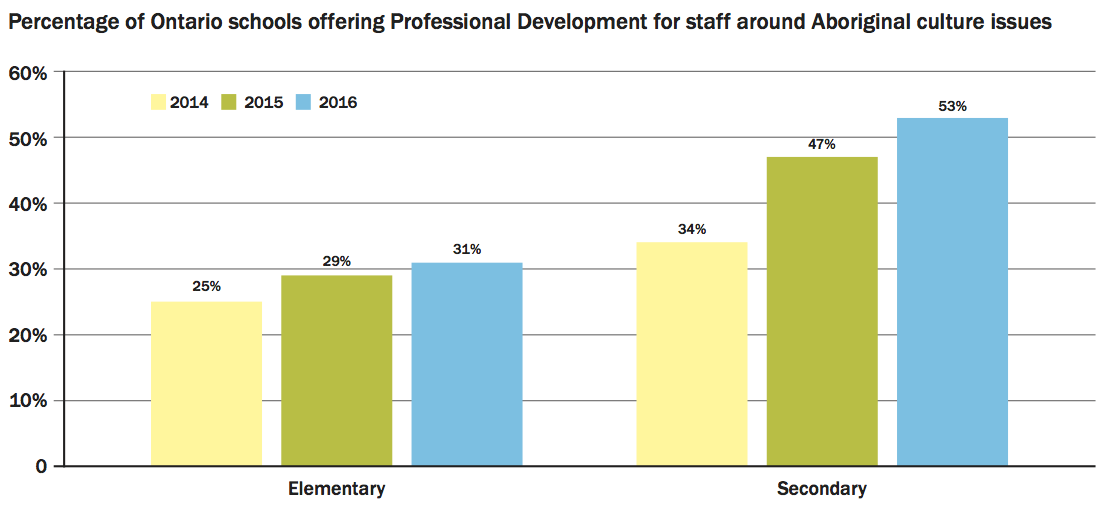

- 31% of elementary schools and 53% of secondary schools report providing professional develop-ment for staff, an increase from 25% and 34% respectively in 2014.

- 29% of elementary schools and 49% of secondary schools report hosting Indigenous guest speakers, an increase from 23% and 39% respectively in 2014.

- 13% of elementary schools and 38% of secondary schools report consulting with Indigenous community members, an increase from 12% and 27% respectively in 2014.

While there has been marked progress toward embedding Indigenous education into Ontario’s schools, there are still challenges to be addressed:

- The majority of schools do not offer Indigenous education activities such as language programs, cultural support programs, guest speakers, and ceremonies.

- Secondary schools have a much higher rate of participation in Indigenous education initiatives than elementary schools.

- Rural areas are more likely to provide Indigenous education and supports than urban communities (this may be a reflection of the higher propor-tions of First Nations, Métis and Inuit students in rural schools).

- Some survey respondents commented that their schools contained too few First Nations, Métis or Inuit students to warrant a specific focus on Indigenous education, illustrating the need to ensure that educators understand that Indig-enous education is important for all

SUPPORTING TEACHERS’ PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The TRC, in its Calls to Action, recognized that teachers need the appropriate skills, knowledge and resources to “integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into their class-rooms”.12 By developing their knowledge of FNMI histories, cultures, perspectives, and approaches to learning, teachers are better able to support Indigenous students and increase awareness and knowledge among non-Indigenous students.

Results from People for Education’s 2015/16 Annual School Survey show a substantial improvement in professional devel-opment opportunities being provided to school staff. Over the past two years, the percentage of elementary schools offering related professional development has increased from 25%

to 31%. Over the same period, the percentage of secondary schools offering related professional development opportuni-ties increased from 34% to 53%. In one program, 2000 teachers in the Toronto District School Board spent a day at the Aborig-inal Education Centre learning about treaties and land rights.13

Additional research will be needed to evaluate the impact of these professional learning opportunities on teaching and learning in the classroom.

One way to ensure that teaching staff have the requisite knowledge to integrate Indigenous education into their class-rooms is to include courses in Indigenous culture and history in teacher education programs, as the TRC recommended. Some universities have taken great strides in this area:

- York University has embedded Indigenous perspectives throughout its Education program, and offers a BEd (Indigenous Teacher Education) Concurrent program designed “to prepare teacher candidates to meet the needs of teaching Indig-enous material in appropriately respectful ways to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.”14

- Lakehead University has made Indigenous-focused courses a degree requirement for all disciplines.15

- Trent University offers an Indigenous Bachelor of Education program for students who self-identify as Indigenous. The program promises to “put Aboriginal knowledge and perspectives at the forefront of teacher training.”16

However, the majority of universities do not require teacher candidates to take any Indigenous-focused courses, even though Ontario’s teacher education program has been extended from one to two years.

The principal shares her knowledge and experiences from the last few years of training. We work in grade teams to provide educational opportunities for all students on Aboriginal perspectives and culture. We have a community member who will be working with the staff on the Medicine Wheel teachings and the Seven Sacred Teachings.

Elementary school, Toronto DSB

FUNDING CHALLENGES

A common concern among this year’s survey participants was a lack of funding to support Indigenous programming.

On the 2016 surveys, some principals commented that they did not receive as much funding for Indigenous cultural opportunities as schools with higher Indigenous popula-tions. This may be a result of targeted funding in the First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Supplement that provides a base amount to all school boards to support implementa-tion of the FNMI Education Policy Framework, plus additional support for boards with higher proportions of First Nations, Métis and Inuit students.

In the 2016/17 school year, school boards will receive $64 million to support First Nations, Métis and Inuit education. The funding is divided into five categories:

- Native Languages Allocation – $9.9 million;

- First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Studies Allocation – $24.8 million;

- Per-Pupil Amount (PPA) Allocation – $23.4 million; and

- Board Action Plans (BAP) Allocation – $6.0 million.17

This year, for the first time, the Ministry has included funding in the basic per-pupil allocation which school boards must use to establish a supervisory officer-level position focused on the implementation of the First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework. Responsibilities will include “working with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit com-munities, organizations, students and families…supporting programs to build the knowledge and awareness of all stu-dents about Indigenous histories, cultures, perspectives, and contributions; and supporting implementation of Indigenous self-identification policies in each board.”18 Boards are not only required to spend at least half of the targeted amount on this dedicated position, but they must also confirm that any remaining amount has been used to support the First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Framework.

This year the Ministry will also begin to phase in data from the 2011 National Household Survey, which will be used to allocate the Per-Pupil Funding Amount. In addition, 45% of the funding for the Board Action Plans will be allocated based on voluntary Indigenous student self-identification. By the end of the phase-in period, it is expected that the 2016 Census data will be available for use in implementing further updates. More accurate demographic data will help to ensure that funding is allocated where it is needed.

Since the person who carries the Aboriginal portfolio also has numerous other responsi-bilities, and our school would not be a priority school, I feel as though we are missing out on many wonderful learning opportunities for the Aboriginal students within our building.

Elementary school, Superior North CDSB

INDIGENIZING EDUCATION: INTEGRATING INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES

There are several signs of progress in Indigenous education in Ontario’s publicly funded schools. Curriculum is being infused with Indigenous perspectives, more related profes-sional development is being provided to educators, and schools are offering more Indigenous education activities for students. However, the biggest challenge ahead may be in achieving true indigenization of education—the integration of Indigenous perspectives and ways of knowing throughout the education system.

According to Dr. Pamela Toulouse, associate professor at Laurentian University, defining success more broadly, and emphasizing a more holistic, interconnected approach to education would benefit both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. The TRC called for integrating Indigenous knowl-edge and teaching methods into classrooms, and a new paper by Dr. Toulouse outlines how this can be done.19

“Indigenous issues, Indigenous pedagogy and respec-tive educational interconnections complement the holistic aspects of student achievement described in Measuring What Matters. Communities of difference share a vision of success that is highly valuable for all students—a vision based on the recognition that identity, culture, language and worldview are equally critical to literacy, numeracy and standardized notions of assessment.20

Dr. Pamela Toulouse

In her paper, What Matters in Indigenous Education: Implementing a Vision Committed to Holism, Diversity and Engagement,21 Dr. Toulouse describes how Indigenous knowl-edge and teaching methods fit within People for Education’s Measuring What Matters initiative, with its focus on broad-ening the definition of school success beyond literacy and numeracy.22

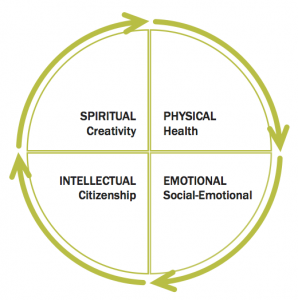

According to Toulouse, the concept of living a good life—a balance between the physical (body and comprehen-sive health), the emotional (relationships to self, others, and the earth), the intellectual (natural curiosity and love of learning), and the spiritual (the lived conscientiousness and footprint that a being leaves in this world) —is an important way of defining success for Indigenous peoples. She frames the competencies and conditions identified in Measuring What Matters within a broader Indigenous worldview through the teachings of the Medicine Wheel.

“The medicine wheel…demonstrates that everything is connected and everything is sacred…Each domain reflects aspects of a human being that makes them whole; the east is the physical, the south is the emo-tional, the west is the intellectual and the north is the spiritual. Balance in each is key.”23

Dr. Pamela Toulouse

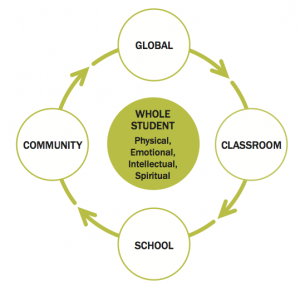

In her paper, Toulouse offers a holistic model of a quality learning environment,with the student in the centre, inter-acting with his or her classroom, school, community, and global environments.

Toulouse identifies and adapts some of the key conditions of quality learning environments identified in the Measuring What Matters framework24 that can have an impact on Indigenous student achievement. These factors are particularly important within the historical context of colo-nialism, racism, social exclusion, poverty, and the many other issues that have an

ongoing effect on Indigenous students:

- A classroom that is welcoming, inclusive of stu-dent voice, and sets high expectations for all stu-dents; where classroom activities are culturally relevant and encourage exploration; and where student learning is expressed in a variety of forms that honour diversity, and challenge stu-dents to try different methods.

- A school environment where leadership is shared and collaboration is valued; where community members with diverse experience work with stu-dents and staff; and where supports are available for students facing challenges.

In examining the conditions in the community that support student success, Toulouse uses an Indigenous definition of ‘community,’ one that is “inclusive of all beings (humans, plants, animals, seen, unseen), and the interconnections that exist amongst them.”25 The key conditions include:

- Meaningful school–community partnerships based in reciprocity, trust, and respect.

- Mental health, anti-bullying, and substance abuse programs that use culturally relevant tools/ resources.

- Support for students to develop enriched definitions of community and engage in action-oriented projects that reflect those expanded descriptions.

- Involvement of Elders, Métis Senators, and knowl-edge keepers in monitoring domain competencies in relation to student learning and school practices.26

In the global context, an Indigenous perspective includes a decolonization focus and “recognizing and living with the earth as our mother.”27 The key competencies include:

- Students understand and “confront the condi-tions and unequal power relations that have created unequal advantage and privilege among nations.”28

- Promotion of Indigenous earth knowledge and sacred connections to land as fundamental to “developing a sense of purpose…[life meaning]… and social existence.”29

- Integrating the “idea of pursuing schooling and education as a communal resource intended for the good of humanity.”30

- Connections with learners across the globe to share experiences and discuss the challenges that these generations face; with creative action as an outcome.

In relation to the other domains in Measuring What Matters— health, creativity, citizenship and social-emotional learning— Dr. Toulouse found alignment with Indigenous beliefs in a holistic approach to education, where education is life-long and focuses on the development of the whole person.

Across Ontario, there is a strong commitment to improving Indigenous education for all students. And real change is evident: this year, for the first time, the Ministry engaged First Nations, Métis, and Inuit education partners in discus-sions on education funding to support equitable outcome for all students; there are improvements in schools’ support for Indigenous learning; and universities are making changes to their programs for future teachers.

In order to ensure that we continue to make progress toward reconciliation:

- The Ministry should establish mandatory curric-ulum on Indigenous education for all Bachelor of Education programs and ensure that all educators receive high quality professional development.

- Currently, Ontario has an Aboriginal Education Office, which falls within the responsibility of the Assistant Deputy Minister for French Language, Aboriginal Learning and Research. The Ministry of Education should appoint a specific Assistant Deputy Minister for Indigenous Education, as called for by the TRC.

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities must be involved at all levels (schools, school boards, and the Ministry) in the development of strategies and professional development for educators to support Indigenous education.

- The Ministry should collect data on Indigenous student achievement in order to be able to mea-sure progress toward closing the achievement gap.

In its Calls to Action, the TRC called for changes that would support teachers in integrating Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into the classroom. People for Educa-tion’s Measuring What Matters initiative provides a potential roadmap for fundamental change in the system. That change may provide a greater chance for success for all students, and for Indigenous students in particular. The measures

of success identified in Measuring What Matters align with the Indigenous belief in a holistic approach to education, where education is life-long and focuses on the development of the whole person. In defining success more broadly, we also make progress toward truly indigenizing the education system and bringing about the reconciliation called for by the TRC.

- Dion, S.D. (2009). Braiding Histories Learning From Aboriginal Peoples Experiences and Perspectives. Vancouver: UBC Press

- Dion, S.D.; Johnston, K.; Rice, C.M. (2010). Decolonizing Our Schools: Aboriginal Education in the Toronto District School Board, p. 35. Retrieved DATE from http://www.tdsb.on.ca/www-docu- ments/programs/aboriginal_voices/docs/Decolonizing%20 Our%20 Schools%203.pdf

- Sinclair, M. (2014). Education: Cause and solution. The Manitoba Teacher 93(3). Retrived from http://www.mbteach.org/library/ Archives/MBTeacher/Dec14_MBT.pdf

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Educa-tion for Reconciliation. In Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Retrieved from http://nctr.ca/assets/ reports/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- Ibid.

- Government of Ontario. (2007). Ontario First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework. Retrieved from https://www. gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/fnmiFramework.pdf. Pg. 6.

- Ibid.

- Ministry of Education, Ontario (2013), A Solid Foundation: Second Progress Report on Ontario’s First Nations, Métis and Inuit Frame-work. Toronto: Government of Ontario, p. 11, citing preliminary data from Statistics Canada’s 2011National Household Survey.

- Ibid. Pg. 28.

- Government of Ontario. (2014). Implementation Plan: Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework. Retrieved from https://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/OFNImplementa-tionPlan.pdf

- Government of Ontario. (2009). Aboriginal Perspectives: A Guide to the Teacher’s Toolkit Retrieved from https://www.edu.gov.on.ca/ eng/aboriginal/Guide_Toolkit2009.pdf; Government of Ontario. (2014). The Ontario Curriculum Grades 1-8 and Kindergarten Program: First Nations, Métis and Inuit Connections. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/ elementaryFNMI.pdf; Government of Ontario. (2014). The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9-12: First Nations, Métis and Inuit Connec-tions. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/ secondary/SecondaryFNMI.pdf

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Educa-tion for Reconciliation. In Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Retrieved from http://nctr.ca/assets/ reports/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf. Pg. 7.

- Brown, L. (2015, December 4). TDSB course mixes art with First Nations studies. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from http://www. thestar.com/yourtoronto/education/2015/12/04/tdsb-course-mixes-art-with-first-nations-studies.html

- York University. (n.d.). Education: General Information. Faculty Rules. Retrieved from http://calendars.registrar.yorku.ca/2012-2013/faculty_rules/ED/gen_info.htm

- Lakehead University (n.d.). Indigenous Content Requirement. Aboriginal Initiatives. Retrieved from https://www.lakeheadu.ca/ faculty-and-staff/departments/services/ai/icr

- Trent University. (n.d.). Indigenous Bachelor of Education. Retrieved from https://www.trentu.ca/futurestudents/program/ indigenous-bachelor-education

- Government of Ontario. (2015) Education Funding: Technical Paper. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Educa-tion, retrieved from https://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/ funding/1617/2016_technical_paper_en.pdf

- Sékaly, G.F. (2016). Grants for Students Needs changes for 2015-16 and 1016-17 [Memorandum]. P.4. Retrieved from http://www. edu.gov.on.ca/eng/funding/1617/2016B06_en.pdf

- Toulouse, P. (2016). What Matters in Indigenous Education: Imple-menting a Vision Committed to Holism, Diversity and Engagement. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: March, 2016.

- Ibid P. 6

- Ibid.

- Cameron, D., Watkins, E., & Kidder, A (2015). Measuring What Matters 2014-15: Moving from theory to practice. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 3, 2015.

- Ibid. P.7

- Bascia, N. (2014). The School Context Model: How School Environ-ments Shape Students’ Opportunities to Learn. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

- Toulouse, P. (2016). What Matters in Indigenous Education: Imple-menting a Vision Committed to Holism, Diversity and Engagement. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: March, 2016. P. 13.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 14

- Sefa Dei, G.J. (2014). Reflecting on Global Dimensions of Contem-porary Education. In D. Montemurro, M. Gambhir, M. Evans & K. Broad (Eds.), Inquiry into Practice: Learning and Teaching Global Matters in Local Classrooms (pp. 9-11). Toronto, ON: Ontario Insti-tute for Studies in Education. Quoted in Toulouse, P. (2016). What Matters in Indigenous Education: Implementing a Vision Com-mitted to Holism, Diversity and Engagement. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: March, 2016. P. 14

- Ibid.

- Ibid.