New data from People for Education show that, despite the widely recognized importance of arts education, equitable access to arts programs and resources is an ongoing challenge for Ontario’s schools. Students in small and rural schools, in schools with higher levels of poverty, and in schools with lower levels of parental education are less likely to have access to learning opportunities in the arts.

- 46% of elementary schools report having a specialist music teacher, either full- or part-time, up from 41% last year

- 98% of secondary schools offer a senior (grades 11/12) Visual Arts class, 92% offer a senior Music class, 86% offer a senior Drama class, and 32% offer a senior Dance class

- Elementary schools with high parental education are twice as likely to have a specialist music teacher than schools with low parental education

- School budgets for the arts range from less than $500 to $100,000

It is hard to understate the benefit derived from an education in the arts. Extensive research on the impact of arts education shows that it supports students’ development in areas ranging from improved spatial reasoning (Hetland & Winner, 2001) to a deepened motivation for learning (Deasy, 2002).

Most significantly, arts education has the potential to enrich students’ creativity and social development (Hunter, 2005). These two qualities are included in the Ministry of Education’s 21st Century Competencies (Ontario, 2015), and make up two of five key learning domains identified in People for Education’s Measuring What Matters initiative (Shanker, 2014; Upitis, 2014; People for Education, 2018).

Despite the widely recognized importance of arts education, equitable access to arts programs and resources is an ongoing challenge in Ontario.

While some schools can offer extracurricular arts activities such as “annual theatre productions,” “monthly coffee houses,” or a “26 week lunchtime program…run by an actor,” their experience is not the norm. Students in small and rural schools, in schools with higher levels of poverty, and in schools with lower levels of parental education, are less likely to have access to learning opportunities in the arts.

Until recently, there was no provincial funding dedicated to the arts. School boards can determine how much funding they allocate to schools for the arts. In some cases, boards allocate money for specific arts initiatives or instructional priorities. For example, some boards provide instrumental music for all students in grades 7 and 8, and will therefore provide some funding to schools for instruments. Other boards provide an instructional budget based on the amount of full-time equivalent (FTE) music specialists at each school.

In addition to board funding, schools can fundraise for things like arts excursions, visiting artists, or musical instruments. Together, the funds raised by the school and allocated by the board contribute to a school’s arts budget for the year.

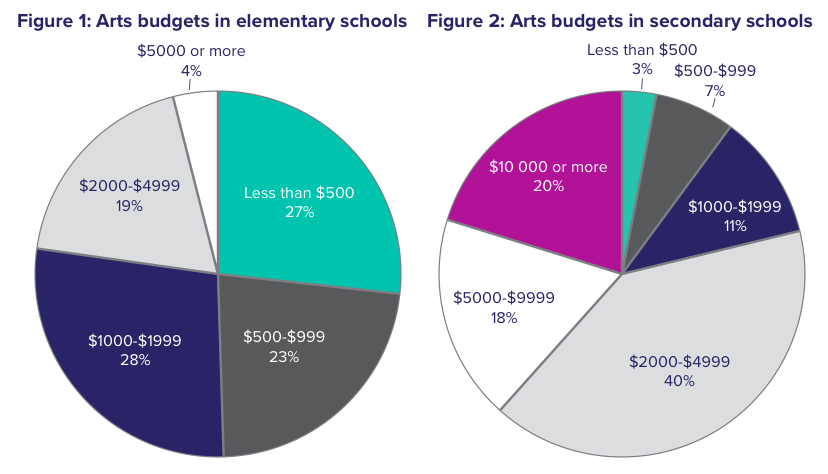

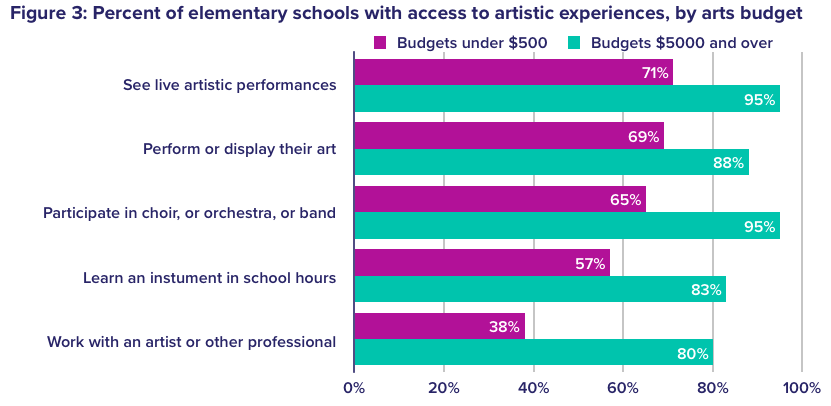

In 2018, People for Education asked elementary and secondary schools about their arts budget. Among elementary schools, these budgets range from under $500 to as high as $20,000 (see Figure 1). At the secondary level, arts budgets can reach as high as $100,000 (see Figure 2).

Both the data and the comments from our survey illustrate the impact of school budgets on access to resources and learning opportunities in the arts. One principal commented that “many instruments sit broken until budgetary bottom lines are determined closer to the end of the year. Even then, not all instruments can be repaired because there is not enough money.”1 Another noted that it is “very difficult to keep up with maintenance and replacement costs”2 associated with their instruments.

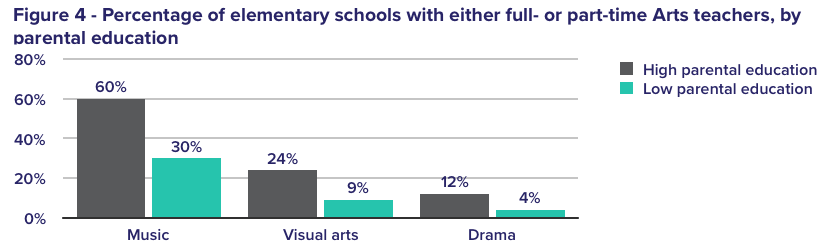

To understand the impact of arts budgets on students’ opportunities to participate in arts enrichment, we examined the difference between elementary schools with the highest and lowest budgets – those under $500 and over $5000. Figure 3 shows that larger arts budgets have a significant impact on arts learning opportunities for elementary students.

Lack of budget to buy musical instruments.

Elementary school,

Conseil scolaire de district catholique de l’Est ontarien

[Translated from French]

In elementary schools, the arts budget also appears to be connected with the availability of arts programming space. Elementary schools with an arts budget of $5000 or greater have, on average, three times as many types of specialty arts rooms as those with arts budgets under $500.

Among secondary schools, there is a correlation between higher arts budgets and the number of senior-level arts courses offered. Furthermore, secondary schools with budgets of $2000 or more are more likely to provide arts-related opportunities than those with budgets under $2000. Secondary schools with budgets of $2000 or more are:

- 11% more likely to be able to display their art

- 15% more likely to see live artistic performances

- 33% more likely to learn an instrument in school hours

- 47% more likely to participate in a choir, orchestra, or band

- 63% more likely to work with an artist or professional from outside the school

1 This comment is from a secondary school in Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB

2 This comment is from an elementary school in Lakehead DSB

There is also a clear link between the amount schools fundraise and the size of their arts budgets. At the secondary level, schools who report fundraising for the arts are 22% more likely to report an arts budget of $5000 or more. At the elementary level, this effect is even more pronounced. Elementary schools who report fundraising for the arts are twice as likely to report a budget of $5000 or more.

When we look at top-decile and bottom-decile fundraising elementary schools, regardless of whether they reported raising money for the arts, the gap widens further. The top fundraising elementary schools are almost three times more likely to have an arts budget of $5000 or more, compared to elementary schools in the lowest fundraising decile.

Much of our arts is funded through our Parent Council, who have prioritized the arts at this school.

Elementary school,

Toronto DSB

Socio-economic status is one of strongest predictors of academic achievement (Davis-Kean, 2005; Sirin, 2005). Many international organizations track socio-economic status through proxies such as parental education, parental occupation, family income, and resources available in the home (e.g. Hooper, Mullis, Martin, & Fishbein, 2017; OECD, 2016).

This year, we used information from Statistics Canada and Ontario’s Ministry of Education to look at the percentage of students from each school whose families’ after-tax income is below the Low-Income Measure. Using our survey sample of elementary schools, People for Education compared the top quartile on this measure — which we refer to as high poverty schools – and the bottom quartile — referred to as low poverty schools. We also looked at the percentage of students from each school whose parents had achieved a university accreditation. Using our sample of elementary schools, we compared the top quartile — schools with high parental education — to those in the bottom quartile — with low parental education.

Low poverty schools are more likely to raise more money per school, more money per student, and more money specifically for the arts, as compared to high poverty schools. Schools with high parental education were 10 times more likely to have an arts budget of $5000 or more, as compared to schools with low parental education.

Individual educators are required to integrate the arts in their classroom instruction, and often they do not have specialized training; therefore, these areas may not receive the attention necessary.

Elementary school,

Sudbury Catholic DSB

Ontario’s arts curriculum covers everything from drama to visual arts, music and dance. It is very detailed, and can pose a challenge for classroom teachers — particularly in elementary schools — if they do not have additional training.

On this year’s survey, many principals commented that their schools struggle with a “lack of specialists” to teach the arts. This concern is supported by the survey data. In 2018, only 46% of elementary schools report having a music teacher, either full- or part-time. While this is an improvement over the 41% of schools reporting music teachers last year, it is still well below the 58% of schools reporting music teachers 20 years ago. Only 16% of elementary schools with grades 7 or 8 report having a specialist visual arts teacher, and just 8% of elementary schools with grades 7 or 8 have access to a specialist drama teacher.

Access to specialist teachers — the impact of school size

One of the factors contributing to the variation in specialist arts staff is enrolment. In this year’s survey, elementary schools with a full-time music teacher average 59% more students than those without any specialist. This is directly connected to funding based on enrolment and teachers’ preparation time.

School boards must provide teachers with preparation time, and that preparation time is usually covered by specialist teachers. Schools with more students have more teachers, which generates more preparation time. As a result, larger schools can hire more specialist teachers to cover that prep time.

The impact of preparation time on access to specialist teachers can be seen in this year’s survey results. As funding for preparation time has increased from the 2016/17 school year to the 2017/18 school year (Ontario, 2016; Ontario, 2017), we are seeing an increase in the overall percentage of elementary schools reporting a music teacher, from 41% in 2017 to 46% in 2018.

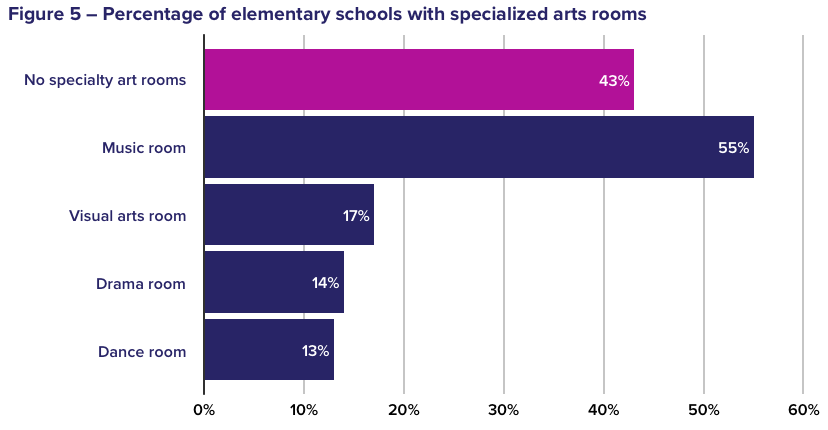

Access to specialist teachers — the impact of parental education

This year’s survey reveals that elementary schools with high parental education were twice as likely to have a music teacher (60% of high parental education schools vs. 30% of low parental education schools), and three times as likely to have a full-time music teacher as those with low parental education. These differences hold even when the data is controlled for region (rural vs. urban) and school size.

This pattern extends beyond music. Schools with grades 7 or 8 in the high parental education quartile are two and a half times more likely to have a visual arts teacher than elementary schools with low parental education. High parental education elementary schools are three times more likely to have a drama teacher than those with low parental education (see Figure 4).

The space will be lost next year as the school board offers the space to provide daycare at the school.

Elementary school, Conseil des écoles catholique du Centre-Est

[Translated from French]

Learning music, drama, dance, and visual arts requires a substantial amount of space – space for instruments and supplies, space for working with different visual arts media, and space to move around. In their comments, survey respondents frequently cite a lack of specialized space as a barrier to providing arts programming. Many principals report that there is no available space because their school is “at capacity,” with one principal commenting that they “barely have storage space, let alone additional space for any learning outside of the normal classroom environment.”3

In this year’s survey, 43% of elementary schools report that they have no specialized rooms for the arts (see Figure 5). Among elementary schools that do have specialized rooms:

- 55% of schools have dedicated space for music

- 17% of schools have dedicated space for visual arts

- 14% of schools have dedicated space for drama

- 13% of schools have dedicated space for dance

Secondary schools are more likely to have specialized arts rooms. Virtually all secondary schools (98%) have at least one room designed for instruction in the arts, and 83% report three or more specialized arts rooms. Visual arts rooms are the most common, with 96% of secondary schools reporting having one. Larger schools are more likely to have more types of specialized rooms.

3 This comment is from an elementary school in Brant Haldiman Norfolk Catholic DSB

At the secondary level, students have access to more specialized arts programs and courses. However, several principals commented that it can be a challenge for students to fit these courses into their timetables.

This year, we asked schools if they offered arts courses in the senior grades (grades 11 and 12). Among the secondary schools participating in the survey:

- 98% of schools offer a senior Visual Arts class

- 92% of schools offer a senior Music class

- 86% of schools offer a senior Drama class

- 63% of schools offer a senior Media Arts class

- 32% of school offer a senior Dance class

- 23% of schools offer Exploring and Creating in the Arts

These senior level courses play a pivotal role for students seeking to develop a career in the arts, and allow all students to continue developing 21st century skills throughout their secondary school experience.

Interest and participation in elective courses (the arts) and art extracurriculars declines as students focus increasingly on graduating in 4 years with 30 credits.

Secondary school,

Waterloo Region DSB

Our school is a small country school with only 8 classrooms. Our teaching staff allotment doesn’t afford us the opportunity to have specialist teachers.

Elementary school,

Lambton Kent DSB

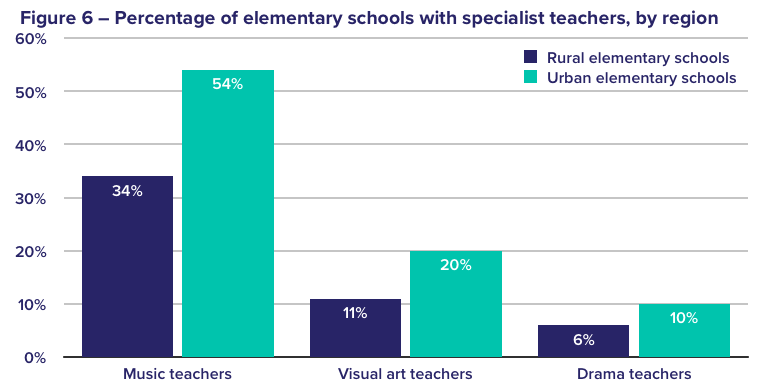

Schools in rural areas face more challenges than their urban counterparts in providing arts education. This year’s survey results show a significant gap between urban and rural elementary schools in the size of their arts budgets; urban elementary schools are three times more likely to have a budget of $5000 or more. Rural schools are also less likely to have specialist drama, visual arts, and music teachers, or specialized arts learning spaces (see Figure 6)4.

While 37% of elementary schools in urban areas report that they do not have any specialized arts rooms, this rises to 53% of elementary schools in rural areas. This pattern holds true even after accounting for the impact of school size, although the gap is not quite as pronounced in similarly-sized schools.

The qualifications held by these educators reveal further disparities:

- Music teachers in rural elementary schools are 9% less likely than those in urban elementary schools to have advanced qualifications

- Drama teachers in rural elementary schools are 68% less likely to have advanced qualifications

This is reflected in the comments on the surveys, with one principal identifying the “recruitment of qualified teachers to come to [their] small rural community”5 as a challenge.

4 Visual arts and drama teachers are calculated among elementary schools that include grades 7 and/or 8 students only.

5 This comment is from a secondary school in Keewatin-Patricia DSB

The cost of arts activities and programs outside of the school day make them inaccessible to many families. This year, using data from student questionnaires completed as part of the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) assessments, we found that overall, 43% of grade three and 39% of grade six students participate in art, music, or drama activities at least once a week when they are not at school.

Unfortunately, the variation in arts resources in schools appears to exacerbate this problem. Both grade three and six students from schools with lower arts budgets were more likely to say they “never” participate in art, music, or drama activities outside of the school day.

Regional disparities in access to specialist teachers and specialized learning spaces also raise concerns about equity in arts education.

Given the significant role that arts education plays in supporting students’ learning and development, our public schools should have equitable access to the resources and programs that support learning in the arts.

Davis-Kean, P.E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294-304.

Deasy, R.J. (2002). Critical links: Learning in the arts and student academic and social development. Washington, DC: Arts Education Partnership.

Hetland, L., & Winner, E. (2001). The Arts and academic achievement: What the evidence shows. Arts Education Policy Review, 102(5), 3-6.

Hooper, M., Mullis, I.V.S, Martin, M.O., & Fishbein, B. (2017). Chapter 3: TIMSS 2019 Context Questionnaire Framework. In I.V.S. Mullis & M.O. Martin (Eds.),TIMS 2019 Assessment Frameworks. Boston, MA: Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center.

Hunter, M.A. (2005). Education and the Arts research overview. Sydney, Australia: Australia Council for the Arts.

Government of Ontario (2015). 21st Century Competencies. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

OECD. (2016). PISA, 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education. Paris, France: PISA, OECD Publishing.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2016). Education Funding: Technical Paper, 2016-17. Toronto, ON: Government of Ontario.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2017). Education Funding: Technical Paper, 2017-18. Toronto, ON: Government of Ontario.

People for Eduation (2018). Beyond the 3R’s. Toronto, ON: People for Education.

Shanker, S. (2014). Broader Measures for Success: Social/Emotional Learning. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014

Sirin, S.R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417-453.

Upitis, R (2014). Creativity; The State of the Domain. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014

Author

Michael Gill

Document Citation

People for Education (2018). Arts education. Toronto: People for Education.

The People for Education tracking survey was developed by People for Education and the Metro Parent Network, in consultation with parents and parent groups across Ontario. People for Education owns the copyright on all intellectual property that is part of this project.

Use of any questions contained in the survey, or any of the intellectual property developed to support administration of the survey, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of People for Education.

Questions about the use of intellectual property should be addressed to the Research Director, People for Education, at 416-534-0100 or [email protected].

Data from the Survey

Specific research data from the survey can be provided for a fee. Elementary school data have been collected since 1997, and secondary school data have been collected since 2000. Please contact [email protected].