30 years with insufficient progress on child well-being

UN report finds Canada behind on implementing Convention on the Rights of the Child

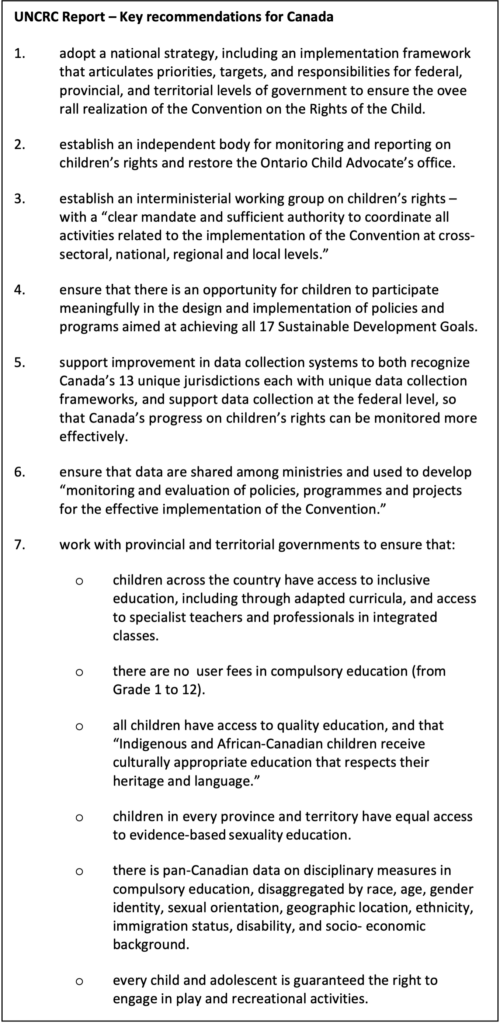

Canada is lagging far behind on implementing the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) – an agreement the country signed onto more than 30 years ago.

Is Canada really the best place in the world to live…for children?

Canada has been called one of the best places in the world to live, but when it comes to the well-being of children and youth, Canada is trailing many other countries. There has been a lack of progress on overcoming disparities for children living in marginalized and disadvantaged situations, such as youth in care, as well as children belonging to Black, Indigenous, and racialized groups, children with disabilities, and migrant children, and in addition, UNICEF’s latest review of child well-being ranked Canada 28 among 38 of the world’s richest countries.

Canada is legally bound to implement the rights and protocols under the UNCRC, but protecting the rights of children, tracking progress, and addressing disparities requires more than simply ratifying international conventions. It requires political will.

Time for pan-Canadian frameworks and monitoring

Without a pan-Canadian monitoring framework to measure education and child well-being outcomes, including comprehensive data collection by age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, national origin, geographical location, and socioeconomic background, it will be impossible to address disparities in access across different areas, or even track targeted measures to address systemic discrimination that affect child well-being.

Progressive realization of rights and People for Education’s Right to Education Framework

Canada is also a signatory to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which committed the governments that signed on, to using the “maximum of [their] available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights.” This model provides a potential accountability structure for monitoring the rights of children and young people in Canada – where goals are articulated, and progress toward those goals is reported on annually.

At the end of November, People for Education will release its Right to Education Framework, which will provide a starting point for this work.

The Right to Education Framework was developed through extensive consultations with experts and with consideration to the salient features of the UNCRC and the many other international conventions, covenants, and agendas that Canada has already signed onto. The Framework defines what a “quality education” should look like in Canada by articulating overarching goals (Access, Accountability, Achievement, Agency), outcomes, and sample indicators that can be developed, measured, and publicly reported by schools, boards, policymakers, and education systems.

Defining what we mean when we refer to quality education in Canada is essential to tracking whether we’re making any progress.

Next review takes place in 2027

The next review of the country’s progress on the Convention on the Rights of the Child will take place in 2027 and if Canada is to take serious action towards protecting the rights of children, including the right of all children to access quality education, there needs to be a transparent and comprehensive monitoring system in place to track education and child well-being, and urgent steps taken to address disparities across population groups.

This can only happen if the rights of all children are both recognized and seen as an essential part of the country’s overall progress. This will take more than making political statements and signing international covenants and conventions. Until such time, Canada is likely to remain a nation, as a recent Unicef report found, “stuck in the middle”.