Calling All Parents

Written by Annie Kidder, Executive Director, People for Education

Article featured in Winter 2020 edition of Principal Connections

Across Ontario and around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in parents being called upon to be teachers, social workers, educational assistants, support staff and mental health professionals. For many families, these added responsibilities are simply impossible to sustain.

It has long been known that a child’s family circumstance is a predictor of their chances for academic success. Children in families struggling to put food on the table, with parents working long hours in precarious employment, and children whose parents did not graduate from high school, are all less likely to do well in school (Pathways to Education). Publicly funded education is supposed to mitigate or at least soften the impact and inevitability of these socioeconomic factors.

But the COVID emergency has exposed – and amplified – deep inequities in the education system. In a time when families are being asked to do more, and often to substitute for the school system itself, the impact of families’ differing capacities is glaringly apparent.

For parents lucky enough to be able to work from home in well-paying jobs that allow some flexibility, who have a high degree of social capital, and a high level of capacity to navigate the education system, the COVID crisis has definitely added to their stress, but ultimately, they – and their children – will manage. On the other hand, parents who were already facing barriers and challenges need more support than they’re currently getting. The big question is: What kinds and what forms of support are needed most?

Parent involvement that makes a difference

It is important to first understand more about the evidence around parent involvement. Whether we’re in a pandemic and kids are learning online, or we’re in “normal times” and kids are attending school in person, what does the research say about the parent involvement that matters most?

In 2011, People for Education decided to take a closer look at the evidence around how parents can make a difference. We looked at studies across thirty years of research, and we were surprised at what we found.

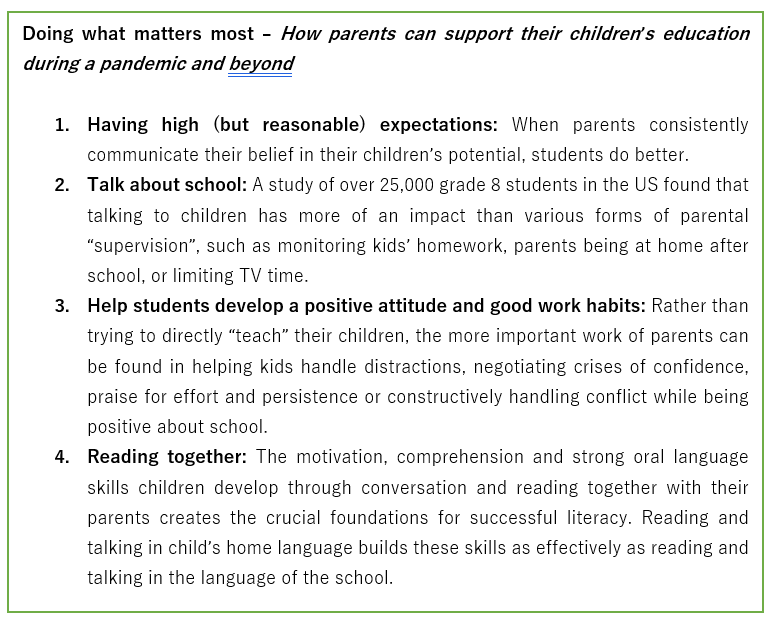

We thought we would read about helping with homework, teaching math by counting things at the grocery store, or volunteering at school. But the evidence was clear. There were four things that parents do that have the greatest impact on helping their children succeed in school, and those four things had nothing to do with being on the school council or finishing children’s projects at two in the morning. The actions with the greatest impact are having high expectations, talking about school, developing students’ work habits, and reading to children. These are things that all families can do, but it is difficult if not impossible to do these things when you are also expected to be your child’s teacher.

So what? Now what?

It may be annoying to suggest that we use this crisis as an opportunity for change, but I am going to suggest it anyway. A group of American researchers who focus on family-school relationships say that the present crisis gives us a chance to stop focusing on the parent involvement we can see (Education Week, October 2020).

Historically, family involvement has been defined narrowly, judged mainly by the physical presence of families in schools – which is impossible during a shutdown. The education profession has rarely asked families how they define “engagement” (or ” family”) and consistently devalues many less visible ways that families support education at home and in the community, such as passing along cultural norms and building educational passion through real-world experiences … COVID-19 can be a catalyst for us to jettison old, school-centred ways of doing things that haven’t worked well.

– Family-School Collaboration Design Research Project, University of Utah

If we know parents can make a difference and we know that the current crisis is amplifying inequities, what does that mean we should do?

First, we must do more to find out what parents themselves say they need. Early in the pandemic, many families were surveyed to find out if they needed laptops and technical support. But have we asked them enough about other needs? Do parents wish they could access human supports such as child and youth workers or tutors? Do they want simple ways to communicate with other parents? Would they like more regular contact with their kids’ teachers? Do they want to know more about what they could be doing at home?

By finding out what parents want, we can then focus on targeting resources, or advocating for structural changes. If parents want to be able to communicate more easily with their kids’ teachers – particularly during the current crisis – then we can advocate for more structured communication time to be built into teachers’ schedules. This will likely require an increase in funding for teachers and other support staff – but the purpose is vital.

If parents say they would like their teenager to have regular support from a child and youth worker, then we can look at what kinds of policies and/or funding need to be in place to make that happen. If parents just want a little more information, then surely a large rich system like Ontario can find a way – through old-fashioned systems like the mail – to get that information to parents, and get it to them in whatever language they speak.

Respecting and supporting parents’ role

Whether students are at home or at school, the world is a stressful place right now. For too long, the education system has either taken parents for granted or been somewhat patronizing toward them. In addition, we have failed to provide dedicated funding for staff to support outreach and engagement with families. Too often this role falls to already over-burdened principals and vice-principals. Results from our 2018 Annual Ontario School Survey show that only 19 per cent of Ontario elementary and 18 per cent of secondary schools have a staff member (other than the principal or vice-principal) acting as a community liaison. And even then, the vast majority have no time allocated to the role (People for Education 2018).

Being a parent is complex. The fact that many, if not most of us have been parents, does not make the role any less significant or any easier. All parents want to do the best for their kids, but they need support. It is up to the system, and those of us working in it, to acknowledge how vital parents’ role is, and to advocate for the structural, policy and funding changes needed to truly recognize parents’ importance.