New study finds relationship between students’ demographics and their Learning Skills marks on report cards

Ontario report cards include more than just marks for subjects like language, math, and science. They also include assessments of students’ Learning Skills and Work Habits.

A recently released report, based on data from the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), found that students with the same levels of achievement on Grade 6 EQAO math tests may have very different assessments of their learning skills, and those assessments differ based on race, gender, and parental education.

Learning Skills are front and centre on report cards

In Ontario, students are evaluated on a four-point scale (Excellent, Good, Satisfactory, Needs Improvement) in six Learning Skills and Work Habits:

- Responsibility

- Independent work

- Initiative

- Organization

- Collaboration

- Self-regulation

While there is an understandable correlation between achieving “Excellent” in Learning Skills and high marks in subject areas, the two areas are supposed to be assessed individually.

“The development of learning skills and work habits is an integral part of a student’s learning. To the extent possible, however, the evaluation of learning skills and work habits, apart from any that may be included as part of a curriculum expectation in a subject or course, should not be considered in the determination of a student’s grades” p. 10 Growing Success (emphasis added)

Although students are given separate marks in each of the six skill areas, TDSB researchers found that there is so much commonality in the marks in the six areas, they act like one variable. This means that if a student receives Satisfactory in the area of Responsibility, for example, it is highly likely that they will be rated Satisfactory in the other five skill areas. For that reason, marks in the six skill areas were collapsed into a single mark for the purposes of analysis.

Comparing learning skills across demographic groups

The study analyzed data from over 7500 students who started junior kindergarten at the TDSB in 2002/03 and graduated from grade 12 in 2015/16. These students also completed the grade 6 EQAO math assessment; had complete Learning Skills data for grade 6; and completed the grade 8 TDSB student census, which collects demographic data from students, including racial identity, gender, parental education, and family status.

For this study, the authors looked at students with the same level of achievement on the grade 6 EQAO math assessment, and then compared the percentage of students who received an Excellent in Learning Skills.

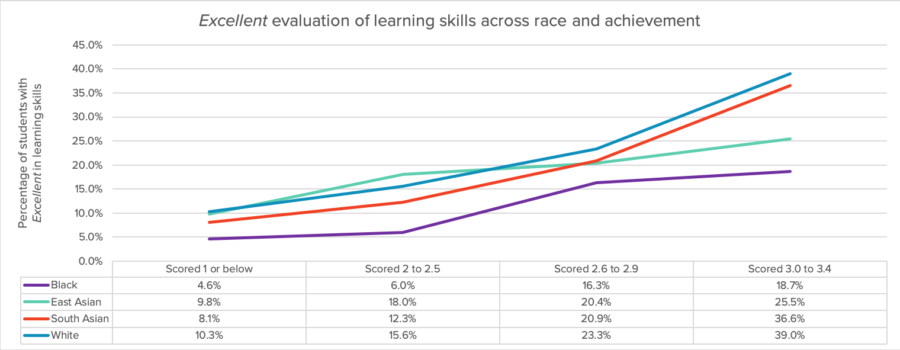

Racial identity

Among students with the same level of achievement on Grade 6 EQAO tests, a higher percentage of students who self-identify as White are rated Excellent in their Learning Skills, compared to students who self-identify as Black. This is true across the four levels of achievement analyzed. Click here to read more about Black student achievement in the GTA.

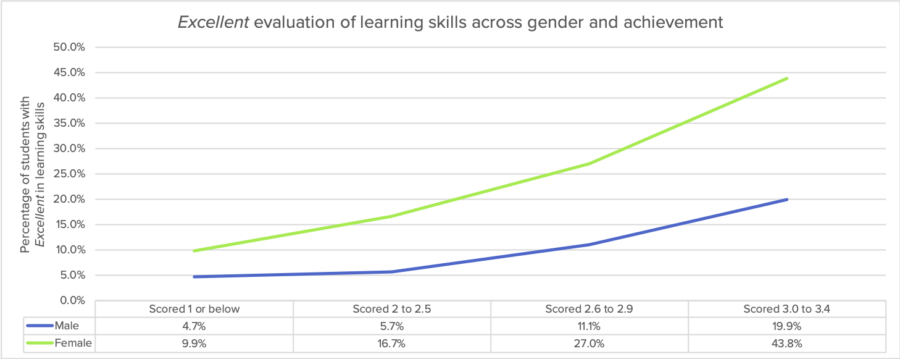

Gender

Females are also more likely than males to receive an Excellent evaluation in learning skills. In fact, looking at those who score at or above the provincial average (3.0 to 3.4), almost half of females were reported to have Excellent skills, compared to one fifth of male students.

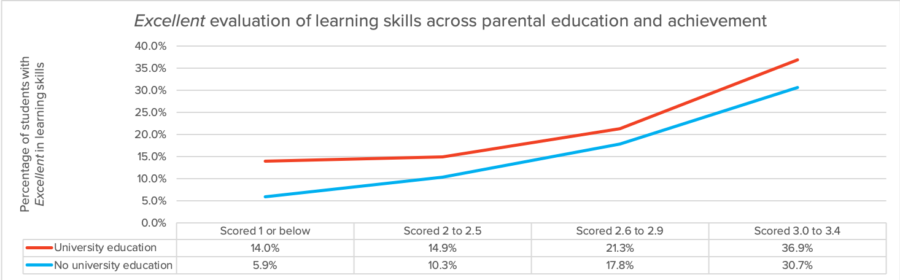

Parental education

Parental education is often used as an indicator of socio-economic status. In this study, students who have at least one parent with university education were more likely to be rated as Excellent in their learning skills across all achievement levels.

Other factors

In the 7,500 cases analyzed, all of the factors above (race, gender, and parental education), as well as special education needs, giftedness, family structure (i.e. living in a two-parent household), and neighbourhood income all influenced the likelihood of a student being assigned Excellent on their report card.

“Trends show that the learning approaches of female students, students self-identified as White, students who have not been identified as having a special education need (excluding gifted), and students who come from historically privileged family contexts (e.g., have access to two parents, parents with university education, and living in higher income neighborhoods) were all perceived to be “better” than the learning approaches of their male, racialized, identified with special education needs, and less socio-demographically privileged counterparts, given the same level of achievement.” p. 19, Parekh, Brown & Zheng, 2018 (emphasis added)

Learning skills matter

Learning Skills and Work Habits are considered a more subjective assessment than marks based on curricular expectations. In Ontario, the Learning Skills are not clearly defined, which makes consistent assessment of the skills more difficult. This may contribute to the finding that they are highly correlated, rather than six separate factors.

The Learning Skills section of the report card can have implications for students’ pathways and futures.

“Whether intentional or not, Learning Skills are used as key indicators by teachers and guidance counsellors in their evaluation of students’ previous and potential achievement as well as in their recommendations for students’ pursuit of academic pathways.” p. 7, Parekh, Brown & Zheng, 2018 (emphasis added)

Overcoming implicit bias

This study casts doubt on the impartiality of Learning Skills assessments and suggests that teachers may be more likely to assign certain groups the label ‘Excellent’.

In Ontario, a large proportion of teachers are White, and 73% of Ontario’s English school teachers identify as female (p. 21). Implicit bias is an unconscious stereotype or belief about certain groups, and it is possible that some teachers see students like themselves as more likely to achieve.

“From the reported Learning Skills’ marks, the results of the study point to a clear bias in favor of students who identify as White, female, nondisabled, and whose parents have university education.” p. 21, Parekh, Brown & Zheng, 2018 (emphasis added)

It can be difficult and uncomfortable for individuals to acknowledge their unconscious bias, but recognizing that this bias exists is an essential step on the road to equity in our publicly funded schools.