Ontario’s publicly funded schools in year two of the COVID-19 pandemic. This year’s Annual Ontario Schools Survey 2021-22 findings show that the issues facing students and educators remain relatively unchanged since last year, and the magnitude, prevalence, and urgency of these issues have only grown.

Last year, People for Education’s (PFE’s) Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS) 2020–21 detailed a story of both challenges and innovation among the province’s publicly funded schools. This year’s AOSS 2021–22 data illuminate a system—and the individuals inside of it—on the brink of breakdown. Students, educators, and school boards across the province have been pushed to their limits, with inadequate resources and little respite. The findings in this report explore the 965 responses PFE gathered from principals across Ontario, representing 70 of the 72 publicly funded school boards in the province. Their perspectives articulate the challenging circumstances facing their school communities.

PFE’s 2020-21 Challenges and Innovations report called for an immediate, clear, and comprehensive recovery plan to enable the education system, its educators, and students to recover from the pandemic and the challenges that came with it. However, this year’s AOSS 2021-22 findings show that the issues facing students and educators remain relatively unchanged, and the magnitude, prevalence, and urgency of these issues have only grown:

- A “fail to fill” staffing situation:

- Stress from the COVID-19 pandemic, compounded by a lack of sufficient funding, and the extension of teacher training in Ontario, have created a staffing crisis in Ontario, with 90% of principals saying that coordinating staffing was a current challenge for their school.

- Insufficient mental health and well-being supports:

- Only 43% of principals agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “My school has the resources necessary to support the mental health and well-being of its students.”

- The challenges posed by hybrid learning models:

- Principals made the challenges associated with hybrid learning clear: increased workloads, stress, and anxiety for educators; a decreased capacity to support students with special needs or disabilities; unrealistic expectations on teachers, as they were asked to be in two places at once; lower rates of student attendance, participation, and engagement; and minimal advance notice provided by the government for planning.

- On top of these challenges, Ontario schools continued to experience disruptions to learning in moving between virtual, in-person, and hybrid models.

- Exacerbated inequities for students on the margins:

- Between trying to meet basic technology needs so that they could participate in their education, and basic needs such as food, shelter, and warm clothing, the pandemic has widened the achievement and engagement gaps for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, racialized students, and students in rural areas.

- Ineffective government support and communication:

- The consistent lack of consultation and communication between the government and school leaders has left many principals feeling overlooked, overworked, and undervalued.

- Principals being pushed to their limits:

- 51% of principals reported that they disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “My recent levels of stress at work feel manageable.”

- Principals reported that an overwhelming lack of support on all fronts—administration, funding, safety resources, and communication from the government—has undermined their capacity to do their jobs.

It is evident that schools need a concise and comprehensive plan to offset the disruptions, stress, and damage that education systems have incurred over the past two years. Ontario needs a clear vision for pandemic recovery, one that will send a strong message to students and educators that they have not been forgotten.

“Where to begin? Staff are completely burned out. Student behaviours are extreme. We have never had the level of challenge we have had this year. Add to this the underlying fear of COVID for staff and their families, and vulnerable loved ones, and there is a perfect storm of stress.” – Elementary and secondary school principal, Northern Ontario

The 2021–22 school year marks the second full school year that students and educators in Ontario’s publicly funded schools have had to navigate constant disruptions, uncertainties, and the above-noted “perfect storm of stress” that built up during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is also the second time that PFE surveyed principals across the province for our AOSS during the pandemic. Last year, we adapted many survey questions to collect preliminary data on how COVID-19 was affecting publicly funded schools in Ontario. Based on the significant challenges highlighted by principals in AOSS 2020–21, principals were asked once again in the AOSS 2021–22 to share their experiences during the second school year affected by COVID-19.

At first glance, the survey data collected in AOSS 2021–22 indicate that Ontario schools continue to face mounting challenges with school staffing and juggling in-person, hybrid, and virtual learning, as well as the growing, urgent need for mental health and wellness supports at school. The most recent findings capture the turbulent reality that Ontario principals, school staff, and students are currently experiencing in an education system pushed to the limits. Early research on the impact of the pandemic on education has already begun to shed light on the growing inequities and potential long-term effects on Ontario students (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2021; Gallagher-Mackay et al. 2021; Tranjan et al. 2022; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 2021; Whitley et al. 2021). Adding to this body of research, this report describes many of the challenges principals are experiencing in Ontario’s publicly funded schools during the 2021–22 school year. Their perspectives best articulate the realities in their school communities.

The staffing shortages have been chronic all fall long: this is definitely an area that I would describe as a crisis. – Elementary school principal, Eastern Ontario

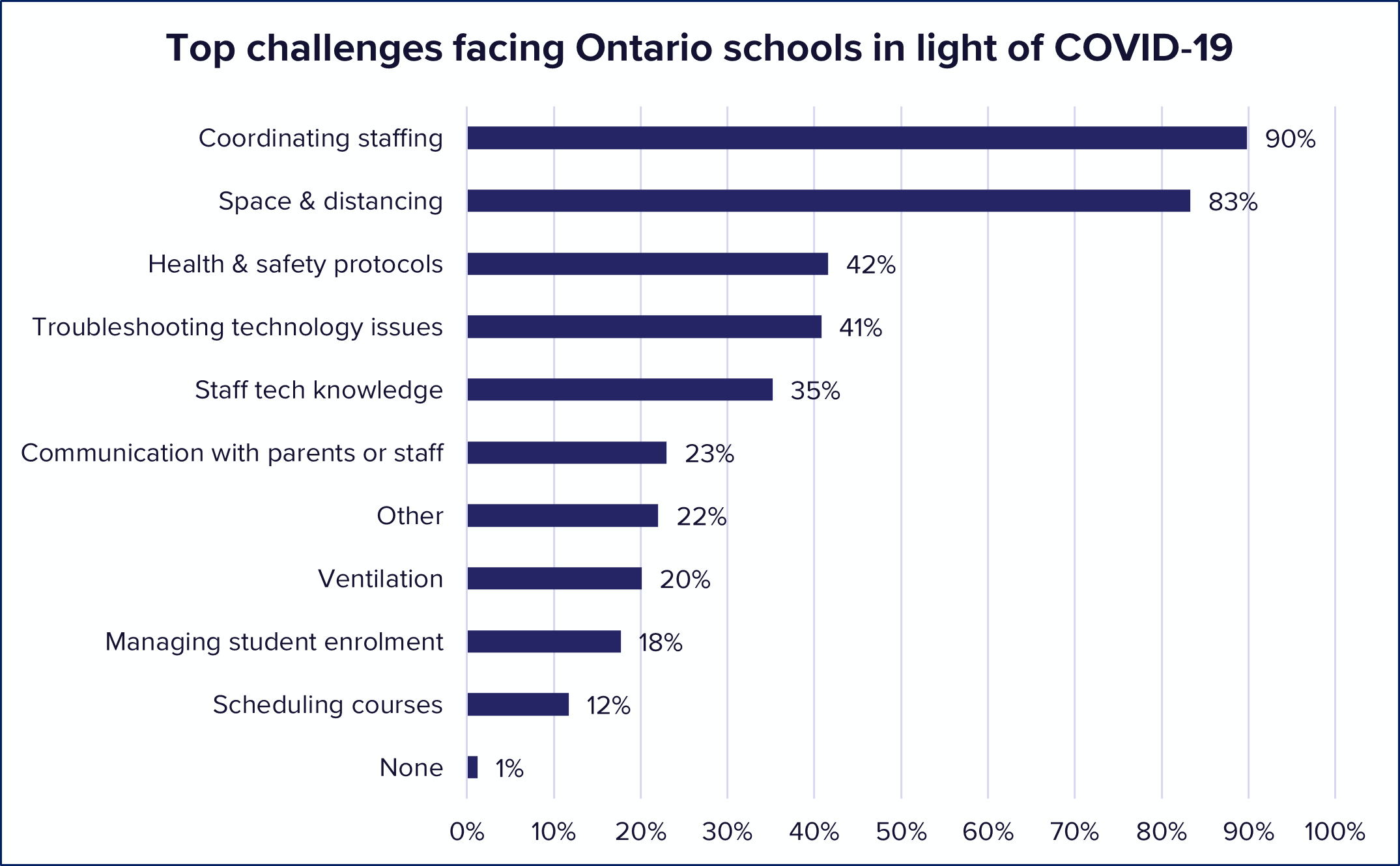

In AOSS 2021–22, principals were asked to indicate the challenges they were facing at their schools in light of COVID-19. The most reported challenge was coordinating staff: 90% of principals said that they faced this challenge, followed by 83% of principals noting space and distancing as challenges (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Top challenges facing Ontario schools in light of COVID-19, AOSS 2021–22

In last year’s AOSS, principals were asked to rank the challenges they were facing because of COVID-19. Principals of both in-person and hybrid schools ranked coordinating staff along with space and distancing as the top three challenges they faced in their schools (People for Education 2021a). More than a year later, principals continue to name coordinating staffing as well as space and distancing as the dominant challenges faced by their schools. Although school staff continues to demonstrate resilience and creativity in facing these obstacles, principals’ responses make it clear that there has been very little progress in addressing the initial challenges brought on by a pandemic that began two years ago.

In last year’s AOSS, principals were asked to rank the challenges they were facing because of COVID-19. Principals of both in-person and hybrid schools ranked coordinating staff along with space and distancing as the top three challenges they faced in their schools (People for Education 2021a). More than a year later, principals continue to name coordinating staffing as well as space and distancing as the dominant challenges faced by their schools. Although school staff continues to demonstrate resilience and creativity in facing these obstacles, principals’ responses make it clear that there has been very little progress in addressing the initial challenges brought on by a pandemic that began two years ago.

The safety and health implications of these staffing shortages were described in a Southwest Ontario elementary school principal’s response:

The number one issue on a daily basis are staff shortages. I cannot emphasize enough how problematic this is for elementary schools, as these students are not old enough to supervise themselves. It is not like in other sectors where others can just compensate by having more patients/clients/customers and it feels busier. This means that children are at risk of being unsafe because there is no one to watch them. We need more supply personnel to keep our schools open and safe. Secondly, we cannot socially distance in classrooms where we have 25+ students. This is especially true of students in portable classrooms. – Elementary school principal, Southwest Ontario

The issues are deeply intertwined. Fewer staff members can lead to larger class sizes, which, in turn, create physical limitations on the amount of distancing possible. In addition to the safety concerns created by these supervision and space dilemmas, principals indicated that these challenges place a heavy burden on teachers and staff, who are asked to give up their preparation time or who find themselves working into the evening and on weekends to catch up on their primary role and responsibilities. This failure to fill staffing vacancies begs the question of why there is a shortage to begin with, and while the answer is complex, there are three contributing factors to note:

- The extension of teacher education from one to two years in Ontario;

- The failure of the Ministry of Education to continue to provide substantial funding increases to support staffing needs for the 2021-22 school year; and

- The compounding impacts of COVID-19 on the public education system.

As early as 1998, Ontario district school boards experienced a shortage of elementary and secondary teachers caused by an uptick in retirements; however, this shortage was short-lived and by 2005, a surplus of new-teacher graduates became the new normal (Ontario College of Teachers 2020). To address this oversupply, the Ontario government expanded teacher education from one to two years beginning in September 2015, reducing student admissions by 50% each year (Ontario Ministry of Education 2013). In 2018, a change in government altered the funding plans for education (Ontario Ministry of Finance 2019; Tranjan et al. 2022). In 2020, the arrival of COVID-19 caused an upheaval in every aspect of people’s lives; for those working in schools, it meant dealing with numerous challenges associated with shifting to virtual learning, followed by the health and safety risks of returning to in-person learning. The logistics of pivoting back and forth also contributed to increased levels of job-related stress, which combined with COVID-related absences to result in a high number of staff absences and leaves. Principals underscored how their staffing shortages were often the consequence of the high rates of absenteeism among their teachers and educational assistants in addition to a lack of available and qualified supply staff.

The compounding impact of a two-year teacher education program, a lack of funding, and the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a staffing crisis across Ontario’s publicly funded schools (Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, 2022). Without sufficient staff, how are schools expected to meet the diverse needs of the student population? These resources, especially school personnel, are potentially more important now than ever before as we address the effects of the pandemic on staff and student mental health and well-being.

While we have been given several online resources it is difficult to use them without sufficient training. It is also difficult for staff to take the time to work through them when they are teaching full time. For myself, it is difficult to take any time off to support the betterment of my mental health as the work never stops and there are limited (to no) personnel to fill in for me. – Secondary school principal, Southwest Ontario

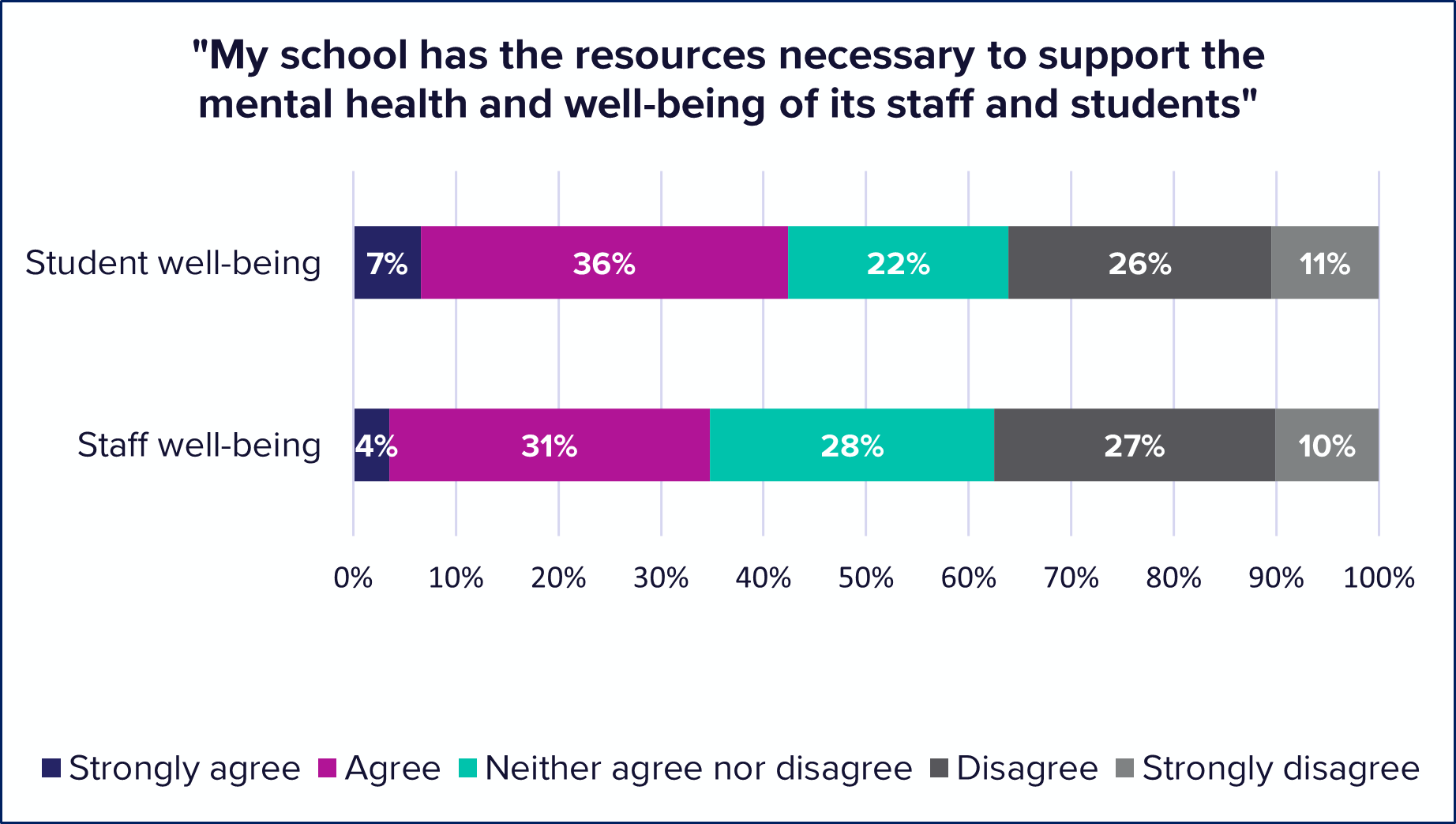

Schools are host to a wide range of staff and child development professionals who are integral to the success and well-being of students. In the best of times, principals noted that these staff—including educational assistants, child psychologists, custodians, early childhood educators, child and youth workers, social workers, administrative assistants, and public health nurses—all work in partnership with teachers to support students’ navigation of their education. However, in AOSS 2021–22, 43% of principals agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “My school has the resources necessary to support the mental health and well-being of its students” (see Figure 2). On the other hand, when asked the same question about support for staff mental health and well-being, only 35% of principals reported that they agreed or strongly agreed. One secondary school principal in Central Ontario elaborated: “The overall impression is that student mental health matters, but staff mental health does NOT matter.”

A smaller proportion of principals agreed or strongly agreed with this latter statement, that they do not have the necessary resources to support the mental health and well-being of their staff, compared with what is available for students. This discrepancy raises important questions about how those working in education have, along with students, been affected by the pandemic and whether appropriate supports have been made available to them.

Figure 2. Principals’ perceptions of the availability of school resources to support staff and student mental health and well-being, AOSS 2021–22

Despite well-documented and studied negative impacts on mental health and well-being from the pandemic, we’ve actually had a DECREASE in school board and community services dedicated to mental health and well-being. – Elementary school principal, GTA

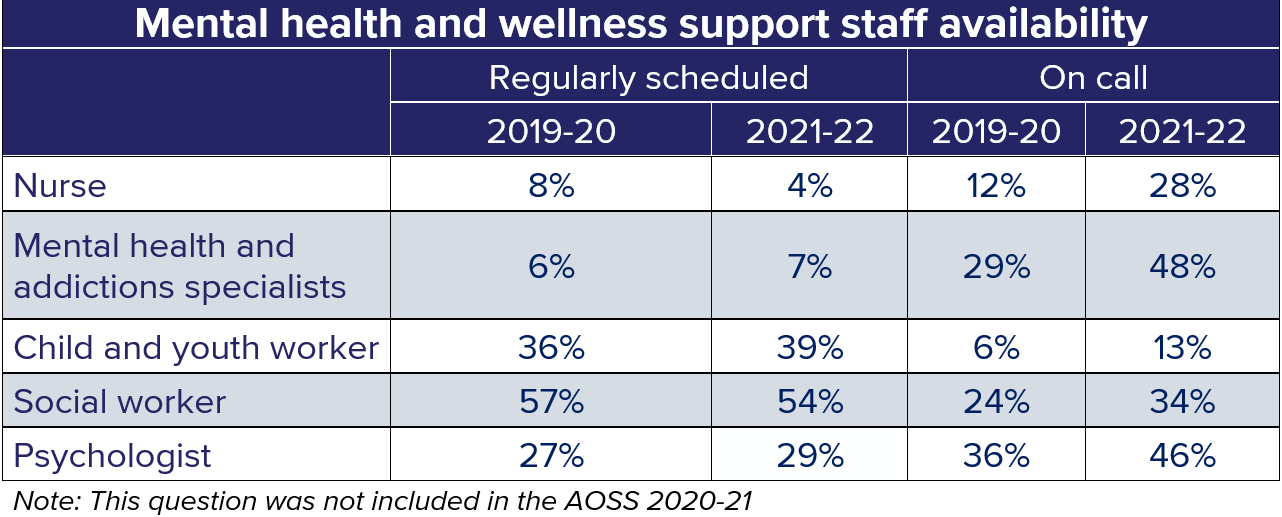

According to

a study from the Mental Health Commission of Canada (2016), more than two-thirds of young adults who live with a mental health problem or illness say that their symptoms first appeared when they were children. Given how much time children spend at school, “the development of the school as a site for the effective delivery of mental health services is essential” (Canada 2006, 138). In AOSS 2019–20, which was conducted before the pandemic, only 6% of Ontario principals noted that mental health and addictions specialists were regularly scheduled in their schools. In AOSS 2021-22, two years into a pandemic that has undoubtedly increased the demand for these supports, the proportion of principals noting that their schools have a regularly scheduled mental health and addictions specialist has increased by just one percentage point (7%). A small increase was also observed in the availability of child youth workers and psychologists. However, decreases occurred in the proportion of principals who had a regularly scheduled social worker (54%) or nurse (4%) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of availability of regularly scheduled and on-call mental health and wellness support workers between the 2019–20 and 2021–22 school years, AOSS 2019–20 and AOSS 2021–22

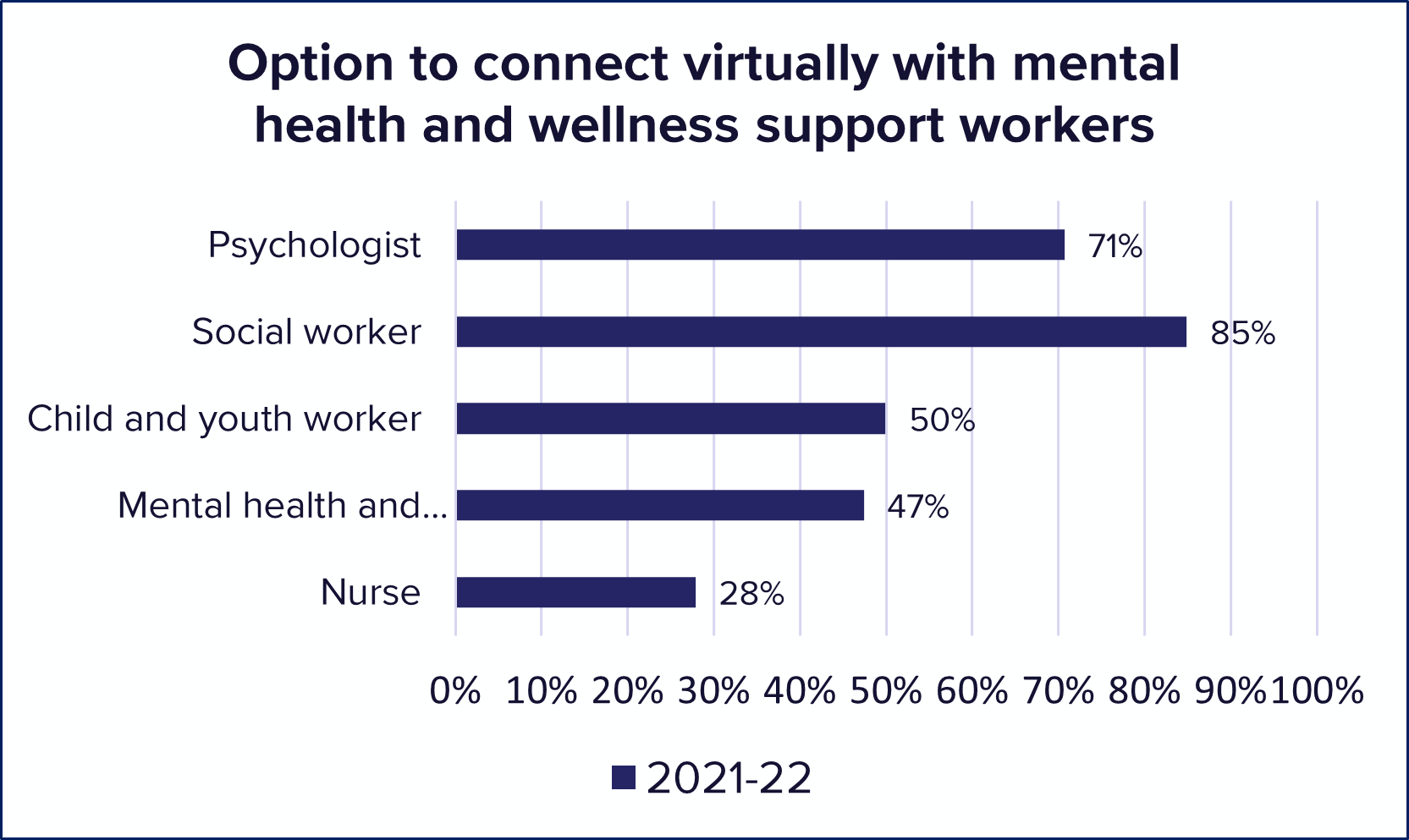

More sizable changes were observed in the on-call availability of mental health and wellness support workers between 2019–20 and 2021–22, which increased for all five of the occupations shown in Figure 3. For the first time, in AOSS 2021–22 principals were provided with the option to indicate whether these support workers offered an option to connect virtually, given how the pandemic has shifted numerous in-person services to an online format (see Figure 4) (People for Education 2020; Whitley et al. 2021).

Figure 4. Proportion of principals reporting an option to connect virtually with mental health and wellness support workers, AOSS 2021–22

Although the option to connect virtually with mental health and wellness support workers can provide flexibility for students and families, principals underscored the drawbacks of this approach. An elementary school principal in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) framed the situation this way: “The biggest challenge is that most of our usual supports have moved to virtual services. This type of model does NOT work for our students and families. Many families experience multiple systemic barriers (e.g., poverty, non-English speaking, health issues, lack of access to tech, etc.).” The increased dependence on technology that has developed due to shifting back and forth between in-person and online learning during the pandemic has instigated important conversations about access and equity in the world of education (Gallagher-Mackay et al. 2021; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2021; Pier et al. 2021; Tranjan et al. 2022; UNESCO 2021; Whitley et al. 2021).

There is not PIVOT as if it were a quick and easy move, it is a staggered crawl. – Elementary school principal, Southwest Ontario

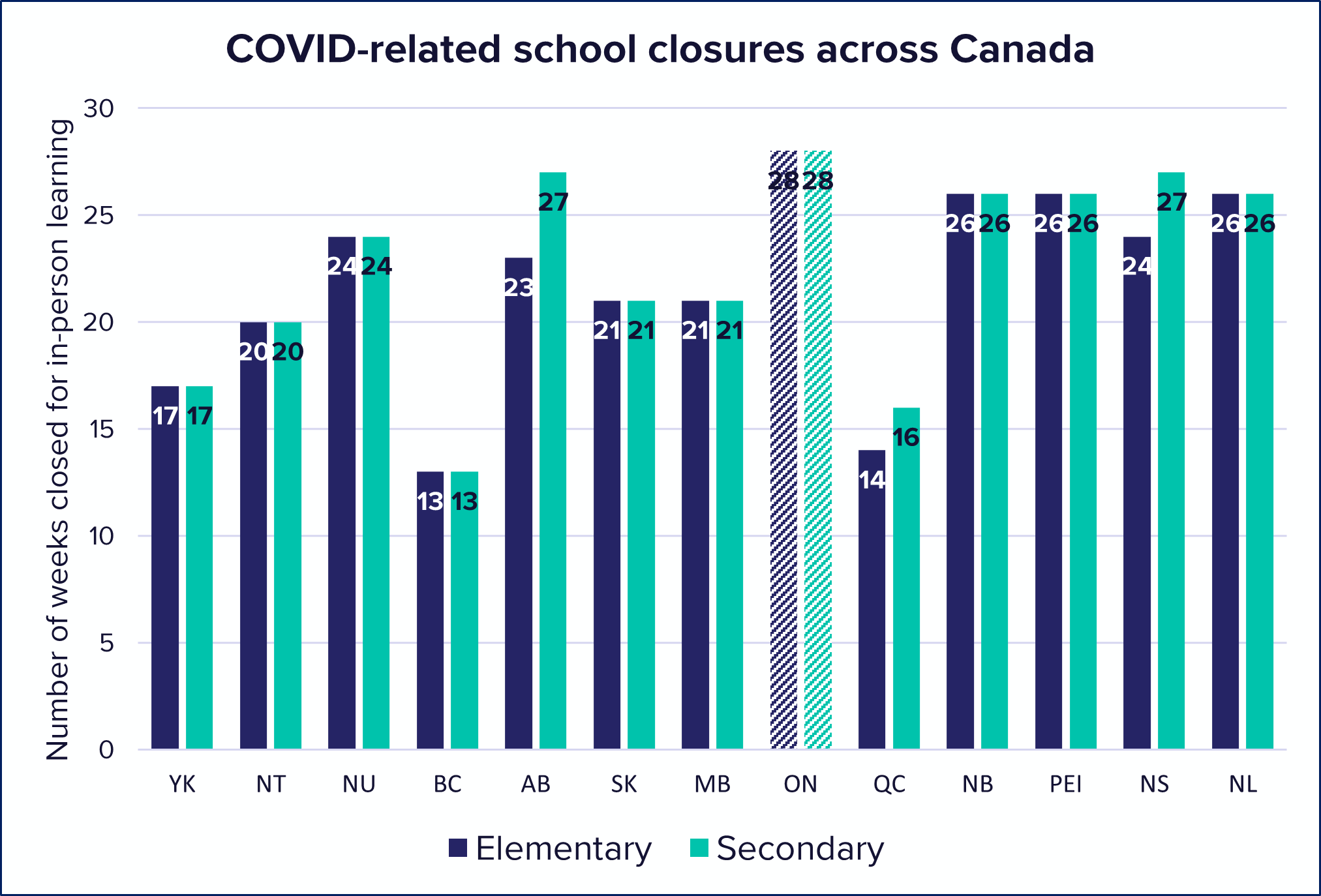

As of February 2022, Ontario led the country as the province with the highest number of weeks of in-person elementary and secondary school closures due to COVID-19 (see Figure 5). The terms “remote learning,” “virtual learning,” and “online learning” could all be used to describe students learning from home via an online platform, either synchronously or asynchronously, as a safety measure due to COVID-19 (Johnson 2021; Gallagher-Mackay et al. 2021). In this report, the term “virtual learning” is used, consistent with the terminology used in the AOSS 2021–22 survey questions.

Figure 5: Weeks of in-person school closures due to COVID-19, elementary and secondary schools, provinces and territories, March 14, 2020 to February 18, 2022

Sources: Values from March 14, 2020 to May 15, 2021 are derived from Gallagher-Mackay et al. 2021; values from January 4, 2022 to February 18, 2022 are calculated from news releases.

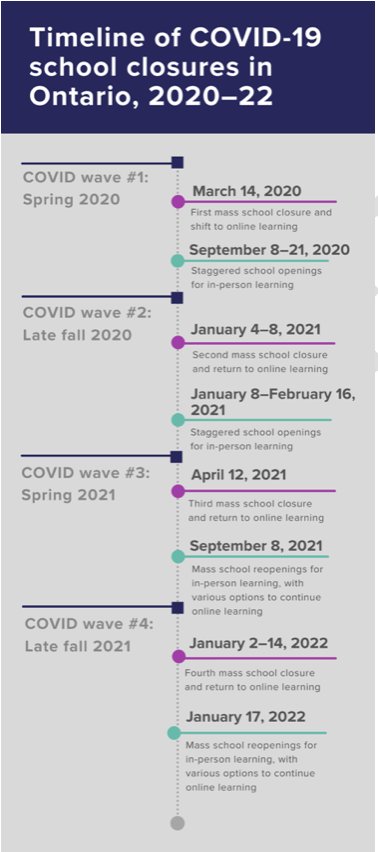

For the past two years, mass school closures in Ontario closely mimicked the fluctuating waves of COVID-19 case counts in the province, causing schools to shift back and forth between in-person and virtual learning on multiple occasions (see Figure 6). Principals responded at length about the challenges created by these changes.

Figure 6: Timeline of Ontario school closures from March 2020 to January 2022

In elementary schools, where students cannot use technology independently and rely on adult support, a shift to virtual learning meant that a significant amount of supervision at home was required; as well, there was an assumption that the supervising adult possessed a certain level of technological literacy. One elementary school principal in Eastern Ontario described the absenteeism that resulted from this situation: “Many of our families are unable to manage or support virtual learning, so when students request virtual, they predominantly request paper packages. We have very high absenteeism…many students have just stopped attending.”

In 2020, the provincial government made it mandatory for school boards to offer full-time online learning as an option for all students in elementary and secondary school (Government of Ontario 2020a). As demonstrated through PFE’s Pan-Canadian Tracker, this is not the case in many other provinces and territories (People for Education 2022). Providing this option added to the complexity of the province-wide shifts between in-person and virtual learning. Although the government and school boards across the province have had a responsibility to be responsive to student need during the pandemic, the decision to mandate virtual learning options for elementary and secondary schools has the potential to permanently alter the quality, control over, and nature of public education across Ontario.

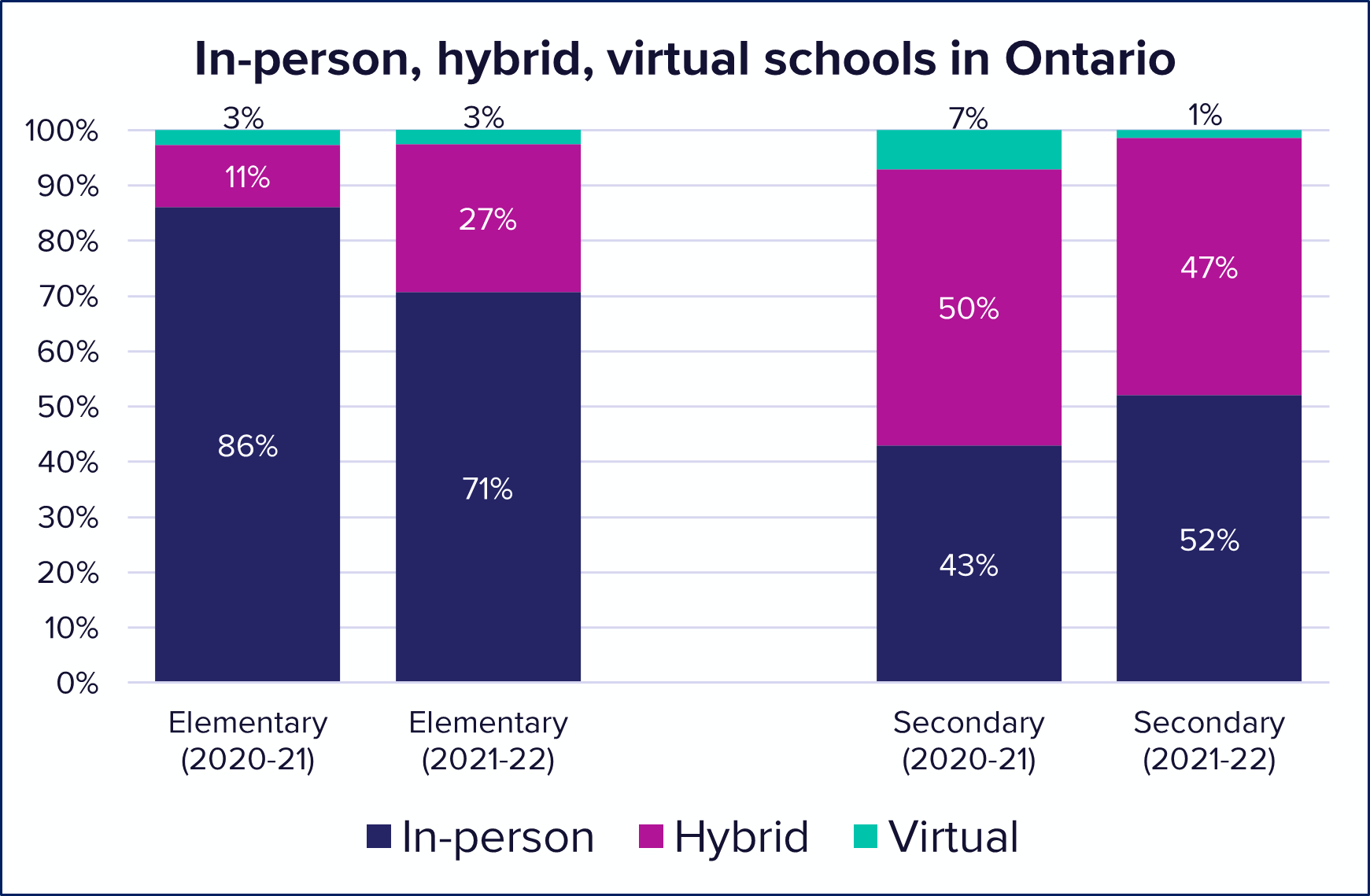

During the 2021–22 school year, the switch between in-person, virtual, and hybrid learning options also created additional administrative demands on educators and divided attention between virtual and brick-and-mortar learning environments (see Figure 7). Principals discussed the disruptive and onerous administrative paperwork that was involved in managing student switches between these modes of schooling. While recognizing the importance of accommodating parents’ desires to be able to change modes throughout the year, principals cited the domino effect on schools that was created each time a student changed their mode of schooling, including coordinating staffing, distributing devices, altering timetables, and tracking attendance.

Figure 7. Type of schooling (in-person, virtual, or hybrid) that principals reported they were responsible for, elementary and secondary schools,2020-21 and 2021–22 school year, AOSS 2020–21 and 2021–22

A comparison of data from AOSS 2020–21 and 2021–22 reveals notable fluctuations in the proportion of elementary and secondary schools that operated in-person, hybrid, or virtual learning. These data were gathered from the question that asked principals to select what type of schooling they were currently responsible for (i.e., at the time of the survey). Although the proportion of schools providing in-person learning decreased for elementary schools, it increased for secondary schools. Moreover, while the proportion of schools providing hybrid learning increased for elementary schools, it decreased for secondary schools. This observation could be explained in part by the COVID-19 vaccine becoming available to youth aged 12–17 as of May 23, 2021. Children aged 5–11 did not become eligible for the vaccine until November 23, 2021 (Government of Ontario 2021). However, hybrid learning remained a common mode of learning in the 2021–22 school year, with 27% of elementary schools and 47% of secondary schools still using this approach.

Hybrid is the most difficult task assigned to teachers to date. – Elementary school principal, GTA

Hybrid learning, sometimes referred to as blended learning, is a combination of online and in-person instruction (Johnson 2021). For educators in Ontario’s publicly funded schools, it is also the approach wherein “students attending face-to-face and students attending remotely will be taught simultaneously by the same educators” via streaming on a technological device (York Region District School Board 2021). Teachers are expected to engage and interact with students in person as well as with students who are learning from home; this expectation includes split-grade classrooms and students with diverse learning needs, and no caps on classroom sizes in grades 4 and up (Government of Ontario 2020b).

The logistics of managing a physical classroom as well as an online learning platform simultaneously are complicated. In AOSS 2021–22, principals were very clear about their perspectives on hybrid learning:

Hybrid learning presents a lot of challenges as each mode of learning requires different planning and full supervision. It is a challenge to keep both meaningfully engaged, especially when we have students with special needs. – Elementary school principal, GTA

Hybrid learning is a disaster. Almost every student who started in it chose to leave and go to full-time virtual or return face to face. The stress it puts on staff and students is disproportionate to any advantages. – Elementary and secondary school principal, Northern Ontario

There are several staff who have risen to the challenge and made their hybrid class very successful. Additionally, the hybrid model does offer a seamless switch in the case of students moving on and offline. However, hybrid, as a model, is not ideal at all. The students who are learning from home are competing for attention with the many students learning in the classroom who, quite naturally, get attention first. Teachers try their best but the students who can move into their direct line of vision can get attention first. At the same time, the students in the classroom are having to wait far longer for individual attention if there are various tech difficulties (happens daily). As well, “teachable moments” that occur throughout the day are far more difficult to share with all of the students—running outside to see how far the rainbow stretches across the sky will naturally leave out the students learning from home. – Elementary school principal, GTA

The challenges of hybrid learning include increased workloads, stress, and anxiety for educators; a decreased capacity to support students with special needs or disabilities; an unrealistic expectation that teachers can be in two places at once; lower rates of student attendance, participation, and engagement; and minimal advance notice provided by the government for planning. Nevertheless, in AOSS 2021–22, 37% of principals reported that teachers in their schools were still teaching via hybrid learning.

Although some benefits of virtual learning have been highlighted since the beginning of the pandemic, very little has been documented about any advantages of hybrid learning (Collins-Nelsen et al. 2021; People for Education 2021a). As one elementary school principal in the GTA noted, “It is like teaching swimming and rock climbing in the same class. Not a valuable way to teach or learn.” As well, the stress, increased workload, and balancing act that are demanded of teachers asked to deliver hybrid learning are difficult to ignore. Another elementary school principal in Southwest Ontario wrote that “Hybrid learning is an unreasonable expectation for a teacher. When you try to be everything to everyone you become nothing to no one.”

It will be critical for both policy-makers and school boards to consider the experiences and expertise of school staff when re-evaluating the use of hybrid learning as well as virtual learning in the future, and the implications of these modes of learning on different populations. For example, an elementary school principal in the GTA noted that, “In a low-income school, flipping to online is not as easily accomplished as it is in more affluent schools as the accessibility to devices is just not the same.”

Because of the low socioeconomic status of my families, when a child is sent home with COVID symptoms, families are challenged to get a COVID test done because of various factors; they don’t own a car, can’t get to a COVID-19 testing facility, and then opt to keep them home for 10 days and don’t have technology to support remote learning. – Elementary school principal, Eastern Ontario

One of the dominant themes of the COVID-19 pandemic has been its exposure of the many inequities in our society (Haeck and Larose 2022; Volante et al. 2021). In education, there is no shortage of examples of how power and privilege are key factors in determining the number, as well as the type, of opportunities or challenges faced by students. For example, in spring 2021, PFE reported on the inequity that students from low-socioeconomic-status backgrounds faced in accessing extracurricular activities during the pandemic (People for Education 2021b). Schools in marginalized and low-income areas across Ontario also had higher incidences of COVID-19 than schools in high-income catchment areas (Srivastava et al. 2022).

Although this example primarily focuses on income as a predictor of inequity, it’s also important to recognize the racialization of poverty in Ontario (Colour of Poverty 2019a, 2019b) and the impact of the pandemic on racialized individuals. The shifts back and forth between in-person and virtual learning are not experienced in the same way by all students. A dependence on virtual learning presupposed that every student had access to technological devices (e.g., tablets, laptops, headphones, etc.), a reliable internet connection, and someone to help them troubleshoot technology. Several principals spoke about the logistical obstacles of acquiring enough technology to deploy to students as well as the varying abilities and availabilities of family members in supporting their children in learning from home. Moreover, an individual’s geographical location can play a key role in their access to an internet connection, a challenge that is only exacerbated by irregular transportation to school when in-person learning is taking place.

In addition to the challenges faced by more remote and rural communities, a few principals at Francophone schools expressed frustration about the lack of resources available in French and how this scarcity has affected the ability of their teachers to develop and evolve their understanding of inclusion.

Another inequity that has underpinned the pandemic both inside and outside of education is the fact that an individual’s socioeconomic status is one of the largest determinants of their health, safety, and access to education (Haeck and Larose 2022; Volante et al. 2021). Numerous principals wrote about not having as much time to manage the deployment of technology because their staff was primarily focused on ensuring that the families in their community had food, warm clothing, and other basic necessities.

COVID has brought to a head all the systemic inequities in our small northern town. Poverty and lack of access to services has been hugely challenging for our school community. Many families count on us to feed and clothe their children, and to provide mental health support. Remote learning is a challenge for many students who cannot learn outside a regular classroom. Staff morale is very low. We are trying as much as possible to implement school spirit activities but are so limited due to COVID restrictions. Student morale is very low. – Elementary and secondary school principal, Northern Ontario

The pandemic has exacerbated the inequities in our society, and access to a quality education is no exception. The principals, teachers, and education support staff working tirelessly to support student learning understand these challenges firsthand; however, it is clear that they do not feel that their expertise and on-the-ground experiences are being taken into consideration.

It would be useful to have admin find out about the latest developments in a different format other than watching it on the news. – Secondary school principal, Southwest Ontario

The AOSS 2020–21 report noted the lack of communication between the Ministry of Education and schools more than one year into the pandemic. The recommendation then was that if changes affecting schools could be communicated in advance—even if only by a few hours—it would help principals immensely to prepare their responses to staff, students, and families. One year later, no progress appears to have been made on this front. When asked about some of the challenges faced in the 2021–22 school year, principals across Ontario wrote statements like the following:

I am watching seasoned, strong teachers burn out after attempting to raise awareness that this would happen last school year when we were first advised about the potential scheduling that we in fact now have. The ministry’s constant last-minute announcements without any consultation with those who are required to implement those announcements [is a challenge]. – Secondary school principal, GTA

More lag time between government announcements to schools and the public. School Boards require time to implement such enormous changes. Also, Boards, Public Health and Government need to share the same messaging and strategies with school administration. Right now, the three organizations have different rules and expectations. – Elementary school principal, Southwest Ontario

Competent leadership from the provincial government. It seems like we as principals have been left to fend for ourselves throughout this pandemic and that every decision that is made is a knee jerk reaction after the fact. Having to figure out what is happening, and next steps based on what CP24 and other news outlets share with us is not a great way to lead. – Elementary school principal, GTA

The lack of clear communication from the Ministry is extremely frustrating. It’s maddening that we find things out at the same time as the general public, with no time to prepare or react. I am proud of our staff, students and families who are making the best of a difficult situation. But it’s extremely challenging to find any joy in school right now. – Elementary and secondary school principal, Northern Ontario

Ontario principals say they have not felt supported throughout this pandemic, despite countless recommendations across not only the province but the country, to consult and engage with education stakeholders before making decisions (Hammond 2022; Catholic Principals’ Council of Ontario 2022; Council of Ontario Drama and Dance Educators 2021; Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario 2022; Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation 2022; Ontario Student Trustees’ Association 2022; People for Education 2021a). The consistent lack of consultation and communication between the government and school leaders has left many principals feeling overlooked, overworked, and undervalued.

I am literally the Jack of all Trades and the Master of None. – Elementary school principal, GTA

Principals reported that the severe staffing shortages in schools resulted in multiple gaps in supports needed in an average school day. These included an insufficient number of lunch-time supervisors, front-desk administrators, educational assistants, and supply teachers. These responsibilities are frequently downloaded to principals, who discussed spending their days scrambling to find replacement staff in addition to covering for replacement staff. It is only at the end of the school day that principals cite being able to “start their second jobs,” including reviewing the emails, memos, and directives that are more typically associated with their jobs.

One secondary school principal in the GTA described the impossible task of balancing the administrative tasks related to issues caused by the pandemic with their regular responsibilities: “The biggest challenge, hands down, is the workload of admin. We work basically all day and on weekends. Even with those hours, I don’t believe we are doing the educational leadership we are capable of, nor supporting students to the best of our abilities.” The balancing act required of principals existed long before the pandemic, of course; PFE reported in 2018 that “This year’s [AOSS] survey results make it clear that it is a challenge for today’s principals to find the time to fulfill their role as curriculum leaders, while also managing all of the administrative tasks involving the school building and staff” (People for Education 2018). Although the pandemic on its own is not responsible for this tension, it is clear from the 2021–22 survey data that COVID-19 increased principals’ administrative responsibilities, taking away from the time needed to support professional learning and instruction, among many other tasks.

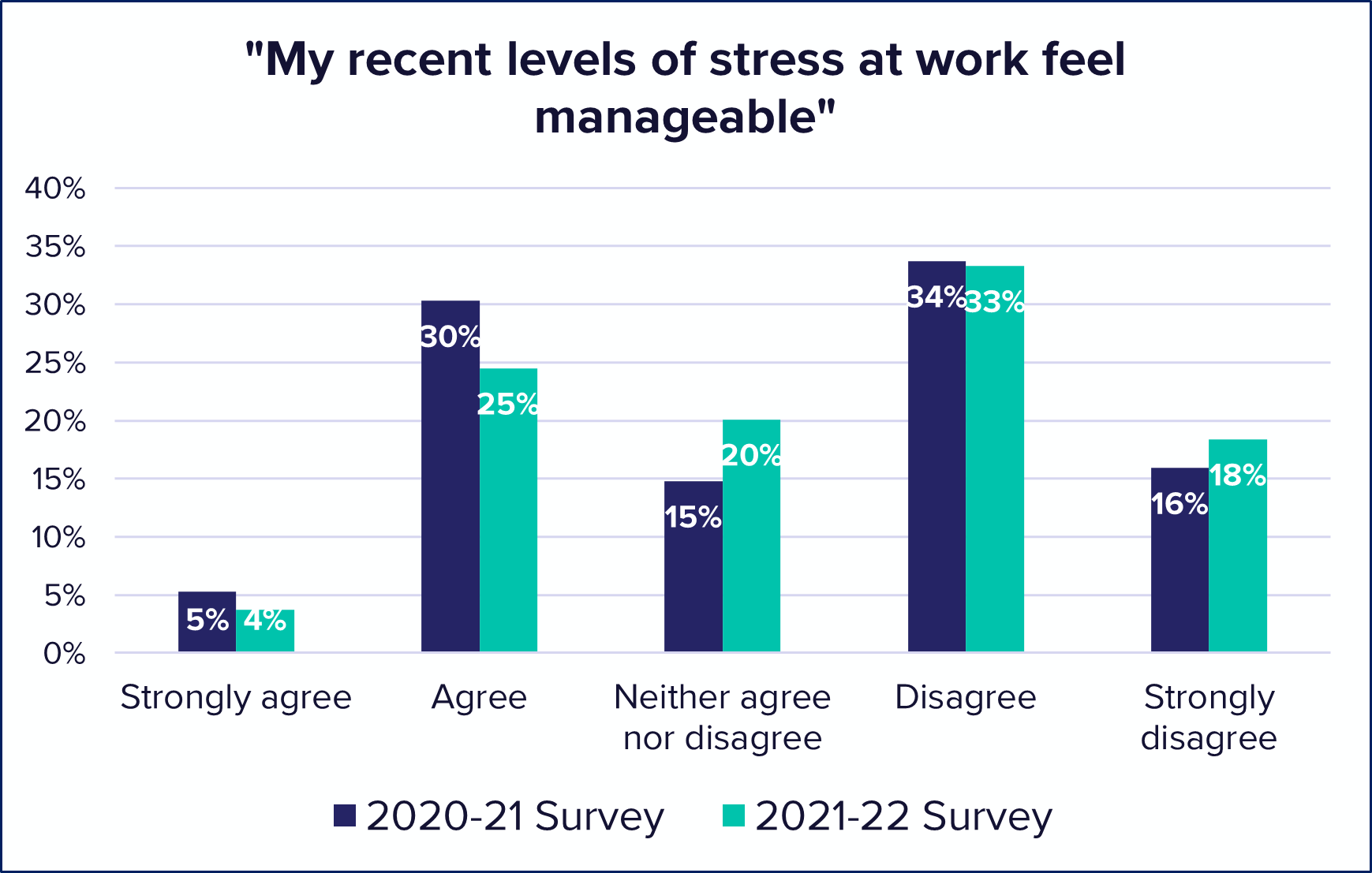

The constant demands involved with managing a school during an ongoing pandemic provide context for principals’ responses to a question from the AOSS 2021–22 that asks about their level of agreement with the statement “My recent levels of stress at work feel manageable” (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Principals’ perceptions of stress at work, AOSS 2020–21 and 2021–22

In this year’s survey, only 29% of principals agreed or strongly agreed that their recent levels of stress felt manageable. This proportion represents a decline of six percentage points from 2020-21, where 35% of principals agreed or strongly agreed with this statement (People for Education 2021a). Moreover, in this year’s survey, 51% of principals reported that they disagreed or strongly disagreed that their recent levels of stress at work feel manageable. An overwhelming number of principals voluntarily elaborated on their responses by writing about the lack of supports provided to them during this pandemic on all fronts—administrative, funding, safety resources, communication from the government—and how this has taken a toll on their well-being and the capacity to do their jobs.

Veteran principals labelled the 2021–22 school year as the most challenging one they have ever experienced; some even noted that, for the first time ever, they were considering early retirement or leaving the profession altogether:

I have been working for the board for 26 years, 14 as an administrator. This has been by far the hardest year, and the year I’ve felt the least supported. With 500 students and no VP, I am only fighting “fires” when our community deserves so much more. This is the first year I’ve ever considered early retirement/leaving the profession. – Elementary school principal, GTA

The panic that the media causes with Covid-19 reporting and speculation has a huge impact on my staff and the parent community. It is a full-time job to keep everyone calm. I find that part of my job exhausting. The constant reassuring and the work that needs to be done to keep staff from going on stress leave is the overwhelming part. – Elementary school principal, Eastern Ontario

I’ve been an administrator in my district for 17 years. These past two years have by far been the most difficult—leading and managing in a pandemic. I know there are no easy answers or solutions, but administrator burnout is real and it’s something that needs to be addressed. This job, albeit immensely gratifying and rewarding, is getting so difficult. Efficacy is also an issue. We want to do the very best for all of our students, but there is only so much we can do with the supports and resources that we have in place. – Elementary school principal, GTA

1 The AOSS 2020–21 was completed in three parts: a fall 2020 survey, a spring 2021 survey, and interviews. Comparisons between AOSS 2020–21 and AOSS 2021–22 data use the fall 2020 survey data only.

One year ago, in the AOSS 2020–21 final report, PFE outlined four key recommendations from principals after Year 1 of the pandemic:

- Consult stakeholders before policy implementation;

- Communicate the changes in advance;

- Fund additional staffing; and

- Broaden access to technology.

One year later, the findings from AOSS 2021–22 are clear: we are experiencing more of the same, but with an added sense of urgency. The fact that there has not been an appropriate response to these calls for action has exacerbated what was already a deeply challenging situation. As Ontario slowly emerges from the most recent wave of COVID-19, it is critical to reflect on what is needed for the public education system to recover from the impact of this pandemic and build back to serve students better.

A significant number of staff on a leave of absence due to stress. Families are undergoing significant stress (job loss, illness, death). Many students have suicidal ideation and/or have made attempts. Significant increase in youth stress and anxiety in the last 3+ yrs. No real supports. School admin are expected to manage all of these pieces on their own while maintaining their own calm. I have to be strong for everyone because they look to me for support. I have a staff member breaking down in my office over stress at least once a week. It’s a lot to take in all the time. There’s a lot of sadness with our students, their families, and staff. – Elementary school principal, GTA

The window to intervene and support student and system recovery from this crisis is quickly closing. Students, families, staff, and education systems have demonstrated tremendous resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic—navigating uncertainty, disruptions, insufficient mental health supports, and staffing shortages—but we can only tell students to be resilient for so long without providing real supports. The lack of action and progress made on the AOSS 2020–21 recommendations demonstrates that—for yet another year—the Ontario government and education system have allowed students, staff, and families to go without the support, resources, and action plan needed to navigate this crisis.

We are in very challenging times—and yet my staff comes to work everyday with a smile on their face and a willingness to improve the lives of the students they teach. They do not feel supported by government—nor do I for that matter. The complete lack of open and honest communication is frightening. Staff look to us as leaders for answers and we don’t have any. We look to our Superintendents for answers—and they don’t have any—we are doing things on the fly—there is no plan. The feeling is that we will simply try this and see if it works—which is ok if that is the plan—but let’s communicate that. Have we thought about what supports we will be able to put in place for so many of our students that are literally two years behind—in early years, K–3—that can create significant gaps that could possibly never be bridged. What is the plan? – Elementary school principal, Southwest Ontario

Although the same four recommendations could be made again in this report, the reality is that we are past the point of recommending that individual needs and recommendations be addressed on an ad hoc basis as a means for recovery. Instead, the four key recommendations from 2020–21 need to be part of a comprehensive and clear plan to manage, assess, and respond to the educational impacts of COVID-19. This plan for education needs to address both short- and long-term recovery for students and the sector.

In January 2022, PFE conducted a pan-Canadian scan of Kindergarten-to-Grade 12 education strategies in response to COVID-19. In this scan, only 4 out of the 13 provinces and territories (Quebec, Nunavut, Yukon, and British Columbia) had developed comprehensive documents that provide a plan to address the ongoing impacts of the pandemic (People for Education 2022). Ontario, and the other provinces and territories, need to be proactive and set a clear vision for pandemic recovery to send a message to young people and educators across the province that they have not been forgotten.

We do have a very strong community at our school that has really come together during the pandemic. I am very proud of our staff and families for persevering and working together to try and keep everyone learning and safe. The effort our staff has put forth in prioritizing our equity and anti-oppression work is a glaring example of how amazing they are in making a difference in our student’s lives. That being said, the toll of the pandemic on our students, families and staff gets compounded as time goes on, and without an increase in supports to keep schools open safely, I fear that despite our in-person learning, the impact of educational funding cuts, especially during a pandemic, on our community will only worsen. Without dedicated funding to mitigate and repair the impacts of pandemic on children, we’re staring at a deeply concerning immeasurable negative impact on public education. – Elementary school principal, GTA

Every year, People for Education (PFE) surveys Ontario’s publicly funded elementary and secondary schools. This report is based on data from the schools that participated in the Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS) 2021–22. Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and quoted material in this report originate from PFE’s AOSS, the 25th annual survey of elementary schools and 22nd annual survey of secondary schools in Ontario. All direct quotations in this report appear exactly as written (including capitalization and emphasis) by survey respondents, unless otherwise stated. Surveys were completed online via SurveyMonkey in both English and French between October 19, 2021, and January 17, 2022.

The AOSS 2021–22 received 965 responses from principals across Ontario, representing 70 of the 72 publicly funded school boards in Ontario and 20% of the province’s publicly funded schools (Ontario Ministry of Education 2021).

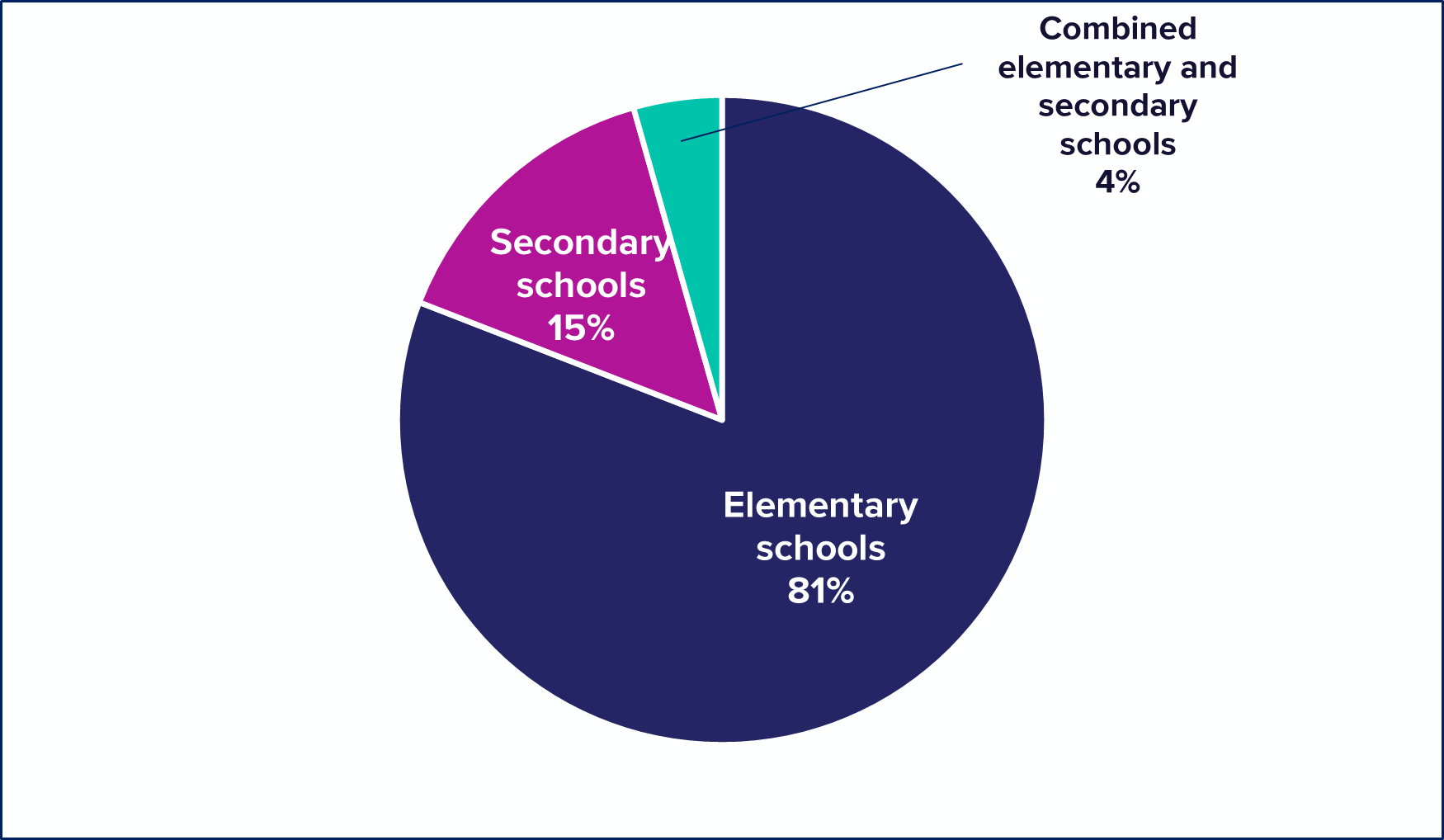

This year, 81% of AOSS 2021–22 surveys were completed by elementary school principals, 15% were completed by secondary school principals, and 4% were completed by principals of schools that house both elementary and secondary students (see Figure 9). In addition, 10% of survey respondents were principals of Francophone schools throughout Ontario. This sample is consistent with the ratio of elementary and secondary schools and the proportion of French-language schools in the larger population of publicly funded schools in Ontario (Ministry of Francophone Affairs 2019; Ontario Ministry of Education 2021).

Figure 9. Proportion of survey responses by school level, AOSS 2021–22

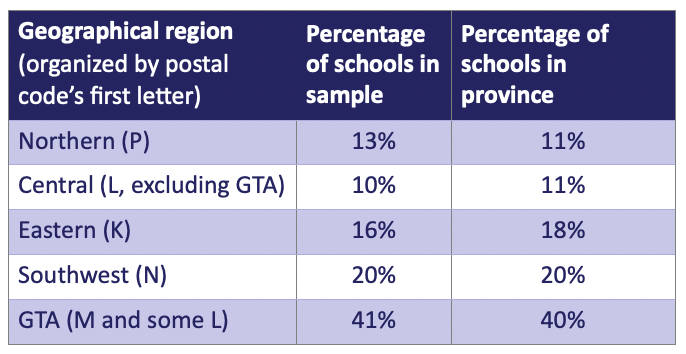

Survey responses were disaggregated to examine survey representation across provincial regions (see Figure 10). Schools were sorted into geographical regions based on the first letter of their postal code. The GTA region includes schools with M postal codes as well as those with L postal codes located in GTA municipalities (City of Toronto 2022, 2020). Regional representation in this year’s survey corresponds relatively well with the regional distribution of Ontario’s publicly funded schools.

Figure 10. Survey response representation by region, AOSS 2021–22

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using inductive analysis. Researchers read responses and coded emergent themes in each set of data (i.e., the responses to each of the survey’s open-ended questions). The quantitative analyses in this report are based on descriptive statistics. The primary objective of the descriptive analyses is to present numerical information in a format that is accessible to a broad public readership. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. All calculations have been rounded to the nearest whole number and may not total 100% in displays of disaggregated categories. Where significant shifts were found in year-over-year comparisons, and changes were noted between survey years, the trends were confirmed by a comparison with the sample of repeating schools (schools that responded to the AOSS in every survey year in a comparison).

For other questions about the methodology used in this report, please contact the Research team at PFE: [email protected].

REFERENCES

Canada. Parliament. Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. 2006. Out of the Shadows at Last: Transforming Mental Health, Mental Illness and Addiction Services in Canada. Final Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Michael J. L. Kirby (Chair) and Wilbert Joseph Keon (Deputy Chair). May 2006. https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/391/soci/rep/rep02may06-e.htm.

Catholic Principals’ Council of Ontario. 2022. “CPCO Statement on Modified Reopening Plans for Schools.” January 3, 2022. https://cpco.on.ca/files/2516/4124/4900/News_Release_-_CPCO_-_Modified_Reopening_Plans_-_January_3_2021_UPDATED.pdf.

City of Toronto. N.d. “City Halls – GTA Municipalities & Municipalities Outside of the GTA.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.toronto.ca/311/knowledgebase/kb/docs/articles/311-toronto/information-and-business-development/city-halls-gta-municipalities-and-municipalities-outside-of-the-gta.html.

Collins-Nelsen, Rebecca, J. Marshall Beier, and Sandeep Raha. 2021. “Bullying, Racism and Being ‘Different’: Why Some Families Are Opting for Remote Learning Regardless of COVID-19.” The Conversation, September 16, 2021. https://theconversation.com/bullying-racism-and-being-different-why-some-families-are-opting-for-remote-learning-regardless-of-covid-19-165063.

Colour of Poverty. 2019a. An Introduction to Racialized Poverty. Fact Sheet #2, March 2019. https://colourofpoverty.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/cop-coc-fact-sheet-2-an-introduction-to-racialized-poverty-3.pdf.

Colour of Poverty. 2019b. Racialized Poverty in Education & Learning. Fact Sheet #3, March 2019. https://colourofpoverty.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/cop-coc-fact-sheet-3-racialized-poverty-in-education-learning-3.pdf.

Council of Ontario Drama and Dance Educators. 2021. CODE Response to Hybrid Learning. September 30, 2021. https://www.code.on.ca/files/inline-files/code_response_to_hybrid_learning_sept_2021.pdf.

Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario. 2022. “Ford Government Confirms Return to In-Person Learning without Consultation.” January 11, 2022. https://www.etfo.ca/news-publications/media-releases/ford-government-confirms-return-to-in-person-learning-without-consultation.

Financial Accountability Office of Ontario. 2022. “Expenditure Monitor 2021-22: Q3.” March 2, 2022. https://www.fao-on.org/web/default/files/publications/FA2106%20Expenditure%20Monitor%202021-22%20Q3/Expenditure%20Monitor%202021-22%20Q3.pdf

Gallagher-Mackay, Kelly, Prachi Srivastava, Kathryn Underwood, Elizabeth Dhuey, Lance McCready, Karen B. Born, Antonina Maltsev, et al. 2021. “COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario: Emerging Evidence on Impacts.” Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table 2, no. 34. https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.34.1.0.

Government of Ontario. 2020a. Requirements for Remote Learning (Policy/Program Memorandum 164). August 13, 2020. https://www.ontario.ca/document/education-ontario-policy-and-program-direction/policyprogram-memorandum-164.

Government of Ontario. 2020b. Ontario Regulation 132/12, Class Size. Education Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.2. September 3, 2020. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/120132.

Government of Ontario. 2021. “COVID-19 Vaccine Bookings to Open for All Children Aged Five to 11.” November 22, 2021. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1001195/covid-19-vaccine-bookings-to-open-for-all-children-aged-five-to-11.

Haeck, Catherine, and Simon Larose. 2022. What is the effect of school closures on learning in Canada? A hypothesis informed by international data. Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique 113, no. 1: 36–43. https://doi.org/10.17269/S41997-021-00570-z.

Hammond, Sam. 2022. “The Return to Remote Emergency Learning Was Not Inevitable.” Canadian Teachers’ Federation, January 6, 2022. https://www.ctf-fce.ca/the-return-to-remote-emergency-learning-was-not-inevitable/.

Johnson, Nicole. 2021. Evolving Definitions in Digital Learning: A National Framework for Categorizing Commonly Used Terms. Canadian Digital Learning Research Association. http://www.cdlra-acrfl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-CDLRA-definitions-report-5.pdf.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. 2016. The Mental Health Strategy for Canada: A Youth Perspective. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Youth_Strategy_Eng_2016.pdf.

Ontario College of Teachers. 2020. Transition to Teaching 2020. https://www.oct.ca/-/media/Transition_to_Teaching_2020/2020T2TMainReportENWEB_V2.pdf.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2013. “Modernizing Teacher Education in Ontario.” June 5, 2013. https://news.ontario.ca/en/backgrounder/25874/modernizing-teacher-education-in-ontario.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021. “Education Facts, 2019–2020 (Preliminary).” Last modified April 21, 2021. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/educationfacts.html.

Ontario Ministry of Finance. 2019. 2019 Ontario Budget: Protecting What Matters Most. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. https://budget.ontario.ca/2019/contents.html.

Ontario Ministry of Francophone Affairs. 2019. “French-Language Schools.” Last updated May 3, 2019. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/french-language-schools.

Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation. 2022. “Letter to Minister Lecce regarding concerns about the January 12, 2022 Ministry of Education guidance to school boards for the resumption of in-person learning.” January 19, 2022. https://www.osstf.on.ca/news/letter-to-m-lecce-re-concerns-about-edu-guidance-to-schools-for-resumption-of-in-person-learning.aspx.

Ontario Student Trustees’ Association. 2022. “Student Concerns Regarding the Return to School Plan.” January 1, 2022. https://osta-aeco.org/blog/2022/01/01/student-concerns-regarding-the-return-to-school-plan/.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2021. The State of Global Education: 18 Months into the Pandemic. September 2021. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/the-state-of-global-education_1a23bb23-en.

People for Education. 2018. Principals and Vice-Principals: The Scope of their Work in Today’s Schools. Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/People-for-Education-report-on-Ontario-Principals.pdf.

People for Education. 2020. Technology in Schools – A Tool and a Strategy. Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/PFE-Technology-in-Schools-Infographic.pdf.

People for Education. 2021a. Challenges and Innovations in Ontario Schools: 2021–20 Annual Report. Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2020-21-AOSS-Final-Report-Published-110721.pdf.

People for Education. 2021b. The Far-Reaching Costs of Losing Extracurricular Activities during COVID-19. Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/People-for-Education-The-Cost-of-Losing-Extra-Curricular-Activities-April-2021.pdf.

People for Education. 2022. Pan-Canadian Tracker: Education Strategies in response to COVID-19 (2021–2022). Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/pan-canadian-tracker-education-strategies-in-response-to-covid-19-2021-2022/

Pier, Libby, Heather J. Hough, Michael Christian, Noah Bookman, Britt Wilkenfeld, and Rick Miller. 2021. COVID-19 and the Educational Equity Crisis: Evidence on Learning Loss from the CORE Data Collaborative. Policy Analysis for California Education. January 25, 2021. https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/covid-19-and-educational-equity-crisis.

Srivastava, Prachi, Tsz Tan Lau, Daniel Ansari, and Nisha Thampi. 2022. Effects of socio-economic factors on elementary school student COVID-19 infections in Ontario, Canada. Preprint, submitted February 6, 2022. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.02.04.22270413v1

Tranjan, Ricardo, Tania Oliveira, and Randy Robinson. 2022. Catching Up Together: A Plan for Ontario’s Schools. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. February 2022. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Ontario Office/2022/02/Catching Up Together.pdf.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2021. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379707.locale=en

Volante, Louis, Don A. Klinger, Livianna Tossutti, and Melissa Siegel. 2021. “Student Achievement Depends on Reducing Poverty now and after COVID-19.” The Conversation, April 19, 2021. https://theconversation.com/student-achievement-depends-on-reducing-poverty-now-and-after-covid-19-153523.

Whitley, Jess, Miriam H. Beauchamp, and Curtis Brown. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Learning and Achievement of Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth.” FACETS 6: 1693–1713. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0096.

York Region District School Board. n.d. “COVID-19: 2021-2022 School Year.” Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www2.yrdsb.ca/about-us/covid-19/2021-2022-school-year.

The Annual Ontario School Survey was developed by People for Education and the Metro Parent Network, in consultation with parents and parent groups across Ontario. People for Education owns the copyright on all intellectual property that is part of this project.

Use of any questions contained in the survey, or any of the intellectual property developed to support administration of the survey, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of People for Education.

Questions about the use of intellectual property should be addressed to the Director, Policy and Research, People for Education, at [email protected].

Data from the survey

Specific research data from the survey can be provided for a fee. Elementary school data have been collected since 1997, and secondary school data have been collected since 2000. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Authors

Jasmine Hodgson-Bautista

Robin Liu Hopson

Jennifer Pearson

© People for Education, 2022

People for Education is an independent, non-partisan, charitable organization working to support and advance public education through research, policy, and public engagement.

728A St Clair Avenue West

Toronto, ON M6C 1B3

Phone: 416-534-0100

Fax: 416-536-0100

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.peopleforeducation.ca

Document Citation

People for Education. 2022. A perfect storm of stress: Ontario’s publicly funded schools in year two of the COVID-19 pandemic.