This report, based on survey results from 1,196 Ontario principals shows there may be a disconnect between provincial policy, which stresses the relationship between guidance programs and overall student success, and the reality in Ontario schools. The vast majority of elementary schools have no guidance counsellors at all, and that in secondary schools the ratio of students to guidance teachers is relatively high.

- Only 14% of Ontario’s elementary schools have at least one guidance counsellor, and of those schools, only 10% have at least one full-time.

- 99% of secondary schools have at least one guidance counsellor. Of those, 88% have at least one full-time.

- The average ratio of students to guidance counsellors per secondary school is 391 to 1.

In Ontario, the government has increasingly articulated policies that stress the relationship between school guidance programs and overall student success.1

Creating Pathways to Success, a new policy introduced by the Ministry of Education in 2013, promotes comprehensive school guidance and outlines how schools should align career and life planning programs from kindergarten through grade 12.

The policy, which was to be fully implemented by the fall of 2014, includes two key components: the creation of portfolios for each student in kindergarten to grade 6, and Individual Pathway Plans to document a student’s learning from grade 7 through to graduation.2 Creating Pathways to Success also envisions an integrated approach to school guidance by seeking to enhance coordination and collaboration between school guidance staff, support staff, and other community stakeholders. The education policy fits well with other provincial initiatives such as the Ministry of Children and Youth Services’ Stepping Stones framework, which supports wider coordination of youth development supports throughout the province.3

In Creating Pathways to Success, the Ministry identifies guidance counsellors as having a “strategic role” in ensuring the success of school guidance programs.4 This is backed up by scholarly research, which has routinely linked the work of guidance counsellors to the effectiveness of overall guidance strategies in supporting student success and a positive school climate.5

Although guidance counsellors in Ontario traditionally focused on helping students select courses and plan for post-secondary education and career opportunities, their work in schools today has become more multidimensional, revolving around not only life and career planning, but also academic skills development, social-emotional development, and mental health.6

Schools report that guidance counsellors provide direct individual support by connecting parents and students to community and school resources, and offering post-secondary and career planning services. As part of collaborative efforts with other school and community support staff, counsellors may also support school-level initiatives that help students choose between academic and applied courses, advocate for students with special needs, and work with teachers in matters related to academic performance, peer relations, student behaviour, and mental health.7

Both the high school and Grade 8 classroom counsellors work collaboratively. There is an excellent partnership with the high school and visits from high school staff several times a year.

Elementary school, Wellington Catholic DSB

Provincial policy requires each elementary school to have a process to document student learning and career and life planning. This process is intended to include reviews with teachers, guidance counsellors and parents.8 However, we found that very few elementary schools have staffed guidance programs. Only 14% of Ontario’s elementary schools have a guidance counsellor, and among that small minority, only 10% have counsellors that are full-time.

The lack of elementary guidance staff has been noted as a concern in Ontario over the past two decades,9 particularly since evidence indicates that the expertise of guidance counsellors in the areas of mental health and child development can be crucial to fostering student success in elementary school.10 Professionally trained guidance counsellors are able to employ evidence-informed strategies to teach students social-emotional skills, and studies suggest that the teaching of these skills is connected to academic performance and behavior.11 Just over three quarters (76%) of elementary schools with guidance counsellors report that their counsellors hold additional qualifications in guidance and career education.

In grades 7 and 8, students make important decisions about high school and often face a range of issues related to adolescence. The course choices that they make may affect their options throughout secondary school and after they graduate.12

Because guidance counsellors in elementary schools can interact with students regularly, they may develop a nuanced understanding of a student over time. The development of these relationships can lead to informed one-on-one support, particularly when students are deliberating between applied and academic courses for high school. But only 20% of schools with grades 7 and 8 have guidance counsellors, and the vast majority are part-time.

It would be wise if grade 8 teachers could communicate with high school principals or guidance. With such strict privacy issues, we have less communication of vital student data, especially for at-risk students/families.

Secondary school, Grand Erie DSB

Some schools increase grade 8 access to guidance expertise by organizing visits and activities with high school guidance counsellors. However, it is unclear how systematic these links are, and to what extent such efforts mitigate the effects of not having an elementary school guidance counsellor.

Guidance counsellors from the local high school visit twice a year with Grade 8 students to inform them about course selection. Grade 8 students also have the opportunity to spend a morning at the high school to experience what a typical day in high school is like. These practices support the transition to high school.

Elementary school, Simcoe-Muskoka Catholic DSB

The methods that schools use to communicate information on course selections appear to be, at least in part, connected to whether or not they have a guidance counsellor. In schools that have guidance counsellors, the main source of information regarding course choices and their implications is more likely to be information nights (62%) than for schools without guidance counsellors (52%). Conversely, schools without a guidance counsellor are more likely to use handouts (22%) to inform parents about high school course selections than schools with a guidance counsellor (12%).

There is no way for a principal of an elementary school of [approximately 500] students with one secretary and no vice principal to know more details on [high school course choices]. My entire day is spent dealing with the urgent and immediate. There is literally no time left to delve into such things. The government trumpets that we’re “curriculum leaders,” yet will not ensure funding is in place and is spent on administrators so that we can actually do such things.

Elementary school, Waterloo Catholic DSB

Across the province, guidance counsellors are much more likely to be found in urban schools, which tend to have larger student populations. This difference may be partly attributed to the provincial funding formula, which allocates the majority of funding to school boards based on the number of students enrolled.13 In our report, we investigated urban accessibility to guidance counsellors by contrasting the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and four other less densely populated regions of the province.

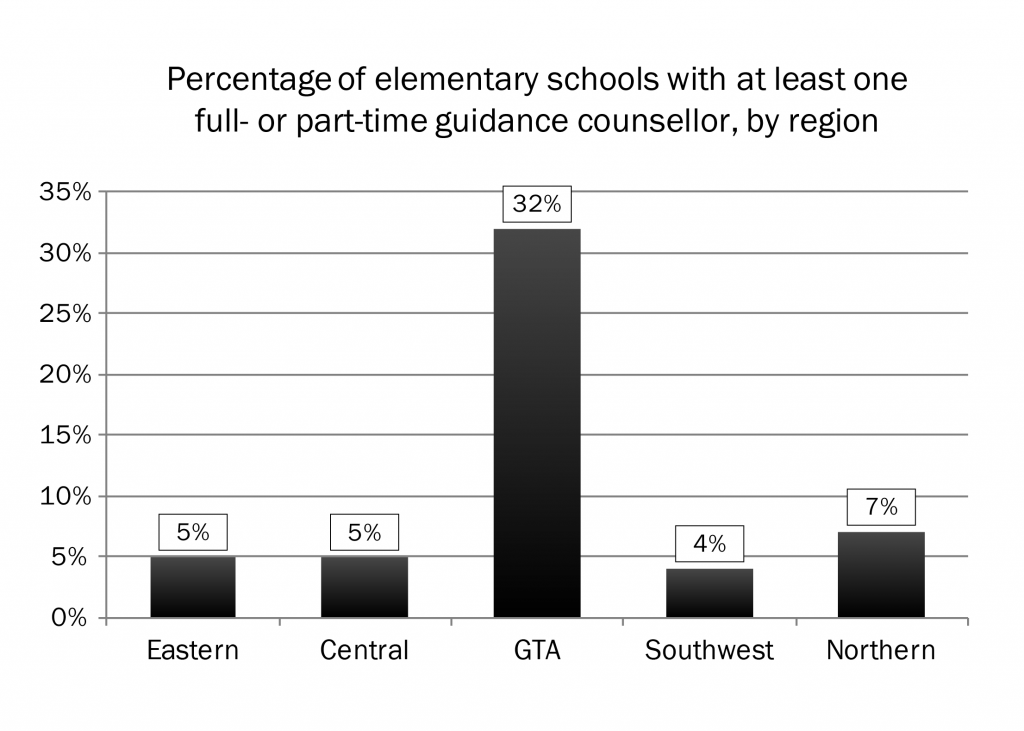

We found that GTA elementary schools were approximately 3 times more likely to have a guidance counsellor. For GTA schools with Grades 7 and 8, 53% had at least one part-time guidance counsellor, and 32% of all GTA elementary schools had at least one part-time guidance counsellor (see Figure 1 for regional comparisons).

Ministry of Education policy outlines the importance of comprehensive guidance programs including the coordination of guidance supports, student well-being, learning competencies, and career and life planning.14

We asked principals to indicate the two areas where they thought guidance counsellors spend most of their time. The majority of principals selected “supporting social-emotional health and well-being,” and “supporting student development and refinement of their Individual Pathway Plans.” Far fewer selected “collaborating with other teachers and social workers,” and “supporting and facilitating learning for students.”

Given these results, there may be the potential to advance the goals of comprehensive school guidance set forth by the Ministry by developing the areas of guidance counsellors’ work that currently receive less emphasis.

In contrast to elementary schools, secondary schools in the province are much more likely to have guidance counsellors. Over 99% of secondary schools report having at least one guidance counsellor, of which 88% have at least one full-time. Of the schools with guidance counsellors, 97% report that their counsellors hold additional qualifications in guidance and career education.

Across the province, the average student–guidance counsellor ratio per secondary school is 391 to 1, and guidance counsellors appear to be relatively evenly distributed throughout schools across the province. The exception is northern Ontario, where 46% of secondary schools report that they only have part-time guidance counsellors—a far higher percentage of part-time counsellors than any other region.

We asked principals to indicate the two areas where they thought guidance counsellors spend most of their time. The majority of principals selected “providing course enrolment advice and guidance” and “supporting student social-emotional health and well-being.” Far fewer selected “supporting student development and refinement of their Individual Pathway Plan” and “collaborating with teachers and social workers;” and very few selected “supporting and facilitating co-operative education and experiential learning for students.”

Similar to elementary school findings, there appears to be a gap between the areas of emphasis that schools indicated and the integrated, comprehensive, and collaborative approach to guidance that the Ministry has outlined.

Using our survey data, we also sought to develop a clearer understanding of secondary school guidance and applied and academic course recommendations. Eighty-nine percent of participating secondary schools indicate that they have initiatives to ensure that students select academic and applied courses appropriately. However, once students have selected courses, there appears to be less support for student transfers from one program of study to another. Nearly half of schools (43%) report that students transfer from applied to academic courses “never” or “not often,” while only 2% report that students transfer “often.”

Research has long documented the importance of integrated school guidance that coordinates the activities of guidance counsellors, administrators, teachers, and community-level support staff.15

In Ontario, the government’s Creating Pathways to Success and Stepping Stones frameworks have aimed for greater integration among different youth development supports throughout the province.16

Social workers working in schools represent a vital component of this support. Part of their responsibility is to support students’ social-emotional development, their well-being, and other aspects of youth development. In schools where they are regularly scheduled, social workers have greater opportunities to get to know school staff and students, and consequently, to form collaborative relationships with school personnel. Through our survey, we set out to better understand connections between schools and social workers by asking schools about their access to social workers. We obtained the following results:

- 75% of secondary schools have at least one regularly scheduled social worker, a steady improvement since 2002, when 46% of schools had them.

- 45% of elementary schools have at least one regularly scheduled social worker, a fairly steady improvement since 2002, when 35% had them.

- 16% of elementary schools in the province have no access to a social worker and no guidance counsellor.

- 28% of elementary schools in northern Ontario have no access to a social worker and no guidance counsellor.

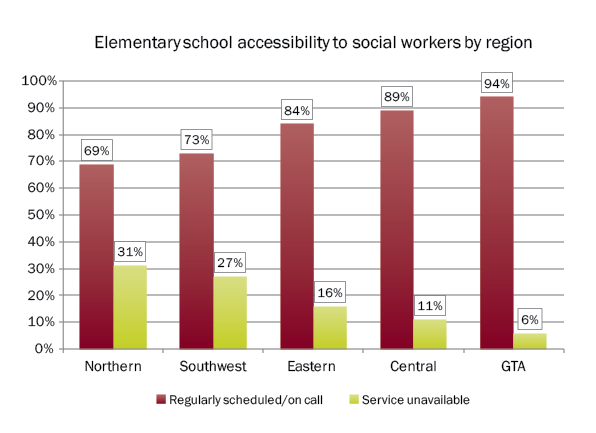

Figure 2 further demonstrates regional disparities in access to social workers’ services. Elementary schools in northern and southwest Ontario are less likely than other regions to have the services of either a regular or on-call social worker available to them (see Figure 2).

Several key implications emerged from our investigation into school guidance.

- Although provincial policy aspires to more comprehensive guidance programs beginning in kindergarten, very few elementary schools have full- or part-time guidance counsellors. This absence of guidance staff may suggest a gap between provincial policy expectations and resources provided at the school level.

- Regional disparities in guidance resources, such as access to school-level guidance counsellors and social workers, were evident throughout our report. Investigating feasible strategies for more even distributions of guidance staff and related resources throughout the province may be an area of future policy consideration.

- The government has asserted the need to integrate guidance activities and other youth development supports. When we asked principals where they felt guidance counsellors spent the most time, only a few chose collaboration with teachers and social workers. Even though access to social workers has improved at both the elementary and secondary levels in recent years, a large number of schools throughout Ontario do not have access to the services of a social worker. This limits potential coordination and the comprehensiveness of school guidance programs. There may be an unrealized opportunity to develop greater coordination both by extending the school-level services of social workers and by enhancing collaborative efforts be-tween school counsellors, school staff, and social workers.

- Principals were much less likely to report that guidance counsellors spent their time supporting and facilitating co-operative education and experiential learning than other guidance activities. Since the province has highlighted co-op and experiential learning as critical to comprehensive school guidance, this finding may signal an area for further development.

- Ontario’s Pupil Foundation grant provides funding for one elementary guidance counsellor for every 5,000 elementary school students. For secondary schools, the province provides funding for one guidance counsellor for every 384 students.

- The funding formula states that “Guidance teachers at the elementary level are those providing guidance primarily to Grade 7 and 8 pupils.” Given the importance of the decisions that students are making in grades 7 and 8, and the issues many of them are facing, we recommend that the province consider increasing funding for elementary school guidance counsellors. If counsellors were funded at a rate of 1 counsellor per 1,800 elementary students, this would match the current level of guidance support that the province provides for secondary school students: approximately 1 counsellor for every 384 students in grades 7 and 8.

Addressing these challenges will likely require both well-structured provincial and school-level initiatives. Nonetheless, such efforts have the potential to enhance comprehensive school guidance and to more closely resemble the aspirations of the existing guidance policy.

Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and quoted material in this report originate from People for Education’s 18th annual survey (2014/15) on school resources in Ontario’s elementary schools and 15th annual survey of school resources in Ontario’s secondary schools.

These surveys were mailed to principals in every publicly funded school in Ontario during the fall of 2014 (translated surveys were sent to French-language schools). Surveys were also available for completion online in English and French. All survey responses and data are confidential and stored in conjunction with Tri-Council recommendations for the safeguarding of data.17 The 2014/15 survey generated

1,196 responses from elementary and secondary schools. This figure equals 28% of the province’s schools. Of the province’s 72 school boards, 71 participated in the survey. The responses provide a representative sample of publicly funded schools in Ontario.

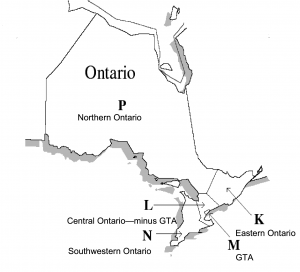

Survey representation by region

Region (sorted by postal code) |

% of schools in survey |

% of schools in Ontario |

| Eastern (K) | 19% | 18% |

| Central (L excluding GTA) | 11% | 17% |

| Southwest (N) | 23% | 20% |

| North (P) | 12% | 11% |

| GTA | 35% | 34% |

Data Analysis

The analyses in this report are based on both descriptive and inferential statistics. The descriptive statistical analyses were conducted in order to summarize and present numerical information in a manner that is comprehensible and illuminating. In instances where inferential statistical analyses are used, we examined associations between variables, using logistic regression analysis. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. For regional comparisons, schools were sorted by region using postal codes. The GTA region comprises all of the schools in Toronto together with schools located in the municipalities of Durham, Peel, Halton, and York.

Reporting

Calculations have been rounded to the nearest whole number and may not amount to 100%.

- Levi, Marion, & Ziegler, Suzanne. (1991). Making Connections: Guidance and Career Education in the Middle Years. Retrieved from Ontario Ministry of Education website: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/reports/ere91016.pdf; Government of Ontario. (2011). Open minds, healthy minds: Ontario’s comprehensive mental health strategy. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.on.ca/; Ontario Ministry of Education. (2013). Pathways to success: An education and career/life planning program for Ontario schools. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/creatingpathwayssuccess.pdf. (Back)

- Ibid. (Back)

- Government of Ontario. (2012). Stepping Stones: A resource on Youth development. Toronto: Author. Retrieved from http://www.children.gov.on.ca/. (Back)

- Pathways to success, see note 1. (Back)

- Carrell, S. E., & Hoekstra, M. (2014). Are school counselors an effective education input? Economics Letters, 125(1), 66-69; Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N. C., & Petroski, G. F. (2001). Helping seventh graders be safe and successful: A statewide study of the impact of comprehensive guidance and counseling programs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79, 320-330. (Back)

- Ontario School Counsellors’ Association (n.d). The role of the guidance-teacher counsellor. Retrieved from https://www.osca.ca/. (Back)

- Pathways to success, see note 1. (Back)

- Ibid. (Back)

- Making Connections, see note 1. (Back)

- Carrell, S. E., & Hoekstra, M. (2014). Are school counselors an effective education input? Economics Letters, 125(1), 66-69. (Back)

- Reback, Randall. (2010a). Non-instructional spending improves non-cognitive outcomes: Discontinuity evidence from a unique school counselor financing system. Educational Finance & Policy, 5(2), 105–137; Reback, Randall. (2010b). Schools’ mental health services and young children’s emotions. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(4), 698–725. (Back)

- King, Alan, et al. (2010). Who doesn’t go to post-secondary education? Toronto: Colleges Ontario. (Back)

- Ministry of Education. (2014) Education funding: Technical paper 2014-15. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/funding/1415/Technical14_15.pdf. (Back)

- Pathways to success, see note 1. (Back)

- Johnson, S., & Johnson, C. (2003). Results based guidance: A systems approach to student support programs. Professional School Counseling, 6(3), 180-4. (Back)

- Government of Ontario. (2012). Stepping Stones: A resource on youth development. Toronto: Author. Retrieved from http://www.children.gov.on.ca/SteppingStones.pdf. (Back)

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, December 2010. (Back)

People for Education is supported by thousands of individual donors, and the work and dedication of hundreds of volunteers. We also receive support from the Atkinson Foundation, Chawkers Foundation, the Counselling Foundation of Canada, the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, the R. Howard Webster Foundation, the Laidlaw Foundation, the Ontario Trillium Foundation, the Toronto Foundation, and the Ontario Ministry of Education.

Every year, principals in schools across Ontario take the time to complete our survey and share their stories with us. And every year, many volunteer researchers help us put the data we collect from schools into a context that helps us write our reports.

Research Director:

David Hagen Cameron

Data Analyst:

Daniel Hamlin

Writers:

Daniel Hamlin

Annie Kidder

Layout:

Megan Yeadon

The People for Education tracking survey was developed by People for Education and the Metro Parent Network, in consultation with parents and parent groups across Ontario. People for Education owns the copyright on all intellectual property that is part of this project.

Use of any questions contained in the survey, or any of the intellectual property developed to support administration of the survey, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of People for Education.

Questions about the use of intellectual property should be addressed to the Research Director, People for Education, at 416-534-0100 or [email protected].

Data from the survey

Specific research data from the survey can be provided for a fee.

Elementary school data have been collected since 1997, and secondary school data have been collected since 2000. Please contact

[email protected].

© People for Education, 2017

People for Education is a registered charity working to support public education in Ontario’s English, French and Catholic schools.

641 Bloor Street West

Toronto, ON M6G 1L1

Phone: 416-534-0100 or 1-888-534-3944

Fax: 416-536-0100

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.peopleforeducation.ca

Document citation

This report should be cited in the following manner:

Hamlin, D. and A. Kidder (2015). Guiding students to success: Ontario’s school guidance programs. People for Education. Toronto: January 26, 2015.