This report includes preliminary findings from the Measuring What Matters field trials in 26 publicly funded schools across 7 Ontario school boards.

Measuring What Matters envisions a public education system that:

-

supports all students to develop the competencies and skills they need to live happy, healthy, economically secure, civically engaged lives; and

-

strengthens Canada—our society, our economy, our environment—by graduating young people with the skills to meet the challenges our country faces.

This vision can be achieved by:

-

setting broad and balanced goals for student success that include numeracy, literacy, creativity, social-emotional learning, health, and citizenship; and ensuring that these goals drive policy, practice, funding, and accountability

The initiative

In a call to action, People for Education launched the Measuring What Matters (MWM) project in 2013. MWM is a multi-year initiative to build consensus and alignment around broader goals and indicators of success for public education.

To accomplish the project goal, People for Education has engaged partners from universities, foundations, and government, as well as education stakeholders from across Canada. An expert Advisory Committee and three smaller working groups in key areas are also making critical contributions to the project. The emerging MWM model, including a set of core competencies and conditions and assessment models, is being field tested by educators in schools and classrooms across Ontario. Based on their feedback, and feedback from consultations, the model will be updated and refined.

The context

Currently, the world is facing challenges in many areas, including wealth disparity, climate change, food security, mass migration, health, gender equality, and stagnating and uneven economic growth.1 In order to address the challenges of tomorrow’s society, young people need more tools than literacy and numeracy. Canada, specifically, is tackling complex environmental, social, and economic issues—a process which requires a variety of competencies, including collaboration, flexible thinking, communication, and information literacy.2 Organizations and thought leaders across Canada and around the world are calling on schools to expand the discussion of “student success” to include a range of broad skills.3 In this project, People for Education—as a champion for public education and a hub of innovative research—is adding its voice to this movement for change.

The goal

The MWM theory of change posits that a renewed education model with broader, integrated goals and measures for student success, will support change both inside and outside the education system. The theory (and recent experience ) suggests that policy and resource allocation in public education will shift to reflect these broader goals. Adopting a renewed model will compel the education system to provide the support, time, alignment, and capacity-building necessary to support educators in fostering their students’ competence and skills in the domains of creativity, citizenship, physical and mental health and social-emotional learning, alongside numeracy and literacy. It will also require new ways to report to parents, students and the broader public about student and system progress in these areas. Over time, this will allow the system to demonstrate progress in these broad and essential areas of student success.

The goal of the Measuring What Matters initiative is to collectively develop, test and propose a new model for education that:

- includes a concrete set of competencies and learning conditions in the areas of creativity and innovation, citizenship, mental and physical health, and social-emotional learning;

- proposes assessment / measurement strategies that focus on, and support these broad competencies;

- supports effective classroom and school practices in foundational areas proven to develop students’ capacity for long-term success; and

- ultimately, informs a productive and useful way to provide parents and the broad public with understandable information about student and system progress in broad areas of learning.

The potential impact

Measuring What Matters is premised on the assumption that policy and practice in education systems is, to a large degree, driven by what the system holds itself accountable for and what is reported to the public. An effective model, that includes competencies and skills in a broad number of foundational domains of learning, will help to ensure that public education is preparing young people to lead happy, healthy, economically secure and civically engaged lives—no matter what their beginnings or their post-secondary destinations.

In its broadest vision, the initiative aims to build consensus around goals for schools and the education system that are aligned with those of post-secondary education and the world of work, and that answer society’s need for an engaged citizenry with the capacity to solve complex problems and thrive in a rapidly changing world.

This focus on a broad view of student success also has the potential to foster cooperation between education and other sectors working to support positive child and youth outcomes. It can foster greater alignment in our goals for young people from Kindergarten through post-secondary education and on into the world of work and adult life and renew public confidence in the purpose and value of public education for youth and society.

Research

Phase one of Measuring What Matters (2013–14) laid the foundations for the project. People for Education conducted a review of the research on broad areas of learning,5 and held public consultations through surveys and focus groups.6

In Phase 2 (2014–15), education experts were recruited to articulate each of the key domain areas, their importance in terms of student success, and some potential ways that they could be assessed.7 They conducted reviews of Ontario’s curriculum and policy to identify where and how each domain is currently recognized, and developed a preliminary set of core competencies, skills, and learning conditions for their domain. The competencies and conditions were viewed as foundational to all curriculum, including literacy and numeracy.

Key activities in 2015–16

Field testing

Field testing in classrooms and schools is a key element of the “proof of concept” approach of the MWM initiative. Through this research, the competencies and conditions are directly grounded in teacher, student, and school experience. In early 2016, People for Education engaged teachers and principals, as well as researchers, curriculum and program consultants, and senior school board leadership in the collaborative development of the field trials. The study included 80 educators in 26 publicly funded schools and seven school boards. (See section 3 for a preliminary analysis of the field trials to date.)

Consultation on measurement

In early 2016, People for Education laid out the conceptual foundation of a whole-system approach to assessment and measurement in broader areas of student success. The scope of the envisioned model explored assessment at the classroom, school and board level, and examined possibilities for complementary jurisdictional-level measures. We then convened a two-day consultation with 20 educational measurement experts, policy makers, and practitioners from across Canada.

Participants recommended re-articulating the goals and the theory of change for MWM in ways that would recognize the long-term nature, and potentially far-reaching implications, of the proposed model. Participants also highlighted the complexity and inherent challenges that will be faced in any dialogue about measurement or about “what matters most.”

MWM involves taking two perspectives at once: a wide-angle view that encompasses the complexity of assessment/measurement in education and the range of contexts in which it happens, and a narrow focus on concrete, specific, teachable/learnable competencies, and practical, implementable approaches to assessment and measurement of these competencies. And all while acknowledging that in education, as in other areas of society, measures are always evolving, as priorities and the “art and science” of measurement evolve.

The consultation raised important questions and caveats to consider as the initiative moves into the next phase:

- How can we think productively about assessment/measurement, without creating an “accountability arms race”?

- What would support greater capacity across the system to en-hance and further support work occurring in these broad areas?

- We need to ensure that equity is always front and centre.

- As we expand the project, how can we bring together diverse stakeholders in a constructive dialogue with People for Education and each other?

Leveraging research networks and partnerships

There are important initiatives underway, both in Canada and internationally, that are exploring broad areas of learning and the potential for broadening the goals and measures of public education. To support Measuring What Matters, People for Education:

- co-convened an ongoing information and data-sharing round table of organizations and ministries doing research from a range of perspectives and using a range of metrics for youth success and wellbeing, in order to share knowledge and data, and seek opportunities for alignment. The roundtable partners include Ontario’s Ministries of Education and Children and Youth Services, UNICEF Canada, the Canadian Index of Wellbeing, YouthRex, and the Ontario Trillium Foundation.

- became a partner in the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation’s WellA-head initiative, which aims to improve child and youth mental health by integrating well-being into school communities.

- co-convened, with the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario and York University, a cross-sectoral table to explore the alignment of approaches to core skills and competencies from K–12 through post-secondary and into the world of work and adult life.

- began participating in the 21st Century Learning group of the Association of Education Researchers in Ontario. This group is exploring the measurement and assessment of 21st Century competencies at school district levels.

- participated in the UNESCO/Brookings Institution International Learning Metrics Task Force and in Skills for a Changing World, an international initiative facilitated by the LEGO Foundation to examine the impact of a focus on play-based learning, creativity and innovation, and student well-being.

Note: These descriptions represent the categorization of competencies within the domains at the time of publication of this report. People for Education continues to work iteratively with MWM domain leads and educators on revisions to the competencies, as researchers learn from the ways educators and students are using and understanding them on the ground through field trials. Click here for the most up-to-date version of the competencies.

The school conditions and student competencies articulated in MWM represent the broad, foundational skills and practices that are critical for students to be successful in today’s society.

The skills and competencies in each domain are intricately connected to the quality of learning experiences, and to the supports available in classrooms, within the school, and in school–community partnerships.

These are captured through a set of conditions for quality learning environments.

Creativity

Creativity is a process that involves generating novel ideas and products, using one’s imagination, being inquisitive, and persisting when difficulties arise. The process includes collaborating with others and being able to evaluate creative products, ideas, and processes dispassionately. Creative competencies and skills are vital for problem solving and for developing ways of adapting knowledge to new contexts.8

Why it matters

In a knowledge economy, and times of rapid change, we need people with the creative capacity to adapt knowledge to new contexts, generate new ideas, and use innovative approaches to problem-solving. Fostering creativity helps students develop resilience, resourcefulness, and confidence, and is positively linked to engagement, achievement, and innovation.

| Creative competencies are grouped into the following categories: | ||

|

|

|

Citizenship

Citizenship education includes the acquisition of knowledge of historical and political concepts and processes. It supports the development of students’ understanding of social issues and of the impact of their behaviour and decisions on others. It develops their capacity to recognize and value different perspectives and their sense of agency to influence change in society.9

Why it matters

A democratic and cohesive society relies on people understanding the impact of their behaviour and decisions on others, and having the capacity to play an informed role in the affairs of their society. Citizenship education supports students’ capacity to be responsible, active citizens in their schools and communities. It allows them to become contributing members of a democratic society.

| Citizenship competencies are grouped into the following categories: | ||

|

|

|

Health

Health education supports students in adopting healthy lifestyles from an early age, and provides them with the self-regulatory skills and competencies they need to make healthy decisions and engage in health promoting behaviours.10

Why it matters

Teaching students the habits and skills that provide a foundation for health improves their chances for academic success. It leads to increased productivity, improved life expectancy, greater capacity to cope with life’s challenges, and can reduce the risk of both chronic disease and mental illness.

| Health competencies are grouped into the following categories: | ||

|

|

|

Social-emotional learning

Social-emotional learning supports students in understanding and managing their emotions, developing positive relationships with others, and engaging with their community. Students can learn social-emotional competencies just as they learn formal academic skills—through regular interactions with peers, teachers, and school staff inside and outside of the classroom.11

Why it matters

Strong social-emotional skills are critical for students’ educational attainment, long-term well-being and prosperity, and their ability to contribute to society.

| Social-emotional competencies are grouped into the following categories: | ||

|

|

|

Quality learning environments

In a quality learning environment classrooms support a dynamic inter-relationship between students, teachers and content; the whole school mirrors ideals of citizenship in democratic societies, and supports social relationships, characterized by trust, interdependence and empathy amongst all members; and school – community relationships focus on students’ well-being, promote cross-cultural perspectives, and provide broader learning opportunities for students.12

Why it matters

The organization of the school, the relationships within it, and the learning “environments” within classrooms influence students’ academic, social, and behavioural learning. The quality of practices and the opportunities to learn, both inside the classroom and throughout the school, play a critical role in developing environments where students can flourish.

| Conditions of quality learning environments are grouped into the following categories: | ||

|

|

|

Full list of competencies and conditions

In the winter of 2016, the MWM team began to field test the competencies and learning conditions developed through the initial research.

This ongoing case study seeks to integrate the MWM framework of competencies into existing educator and school practices in order to develop an understanding of viable approaches to both jurisdictional and local assessment and measurement in these broad areas of learning.

The study marks a critical shift for Measuring What Matters—from one largely substantiated in scholarship and research to one infused and integrated with practitioner knowledge and expertise. The information elicited from the field trials will deepen our understanding of system approaches to assessment and measurement for broader areas of school success.

The goal of the field trials is to answer three interrelated questions:

- What are the implications of using the five domains—creativity, citizenship, social-emotional learning, physical and mental health, and quality learning environments—and related competencies and learning conditions, as a framing and evaluation tool?

- What are the interrelationships between and across the five domains, as expressed in school and school district practices?

- How do the definitions of the competencies and conditions articulated in the MWM framework translate into learning experiences in classrooms?

The study included 80 educators in 26 publicly funded schools across seven school boards. Six of the participating sites were secondary schools and twenty were elementary schools. The schools in the study represented four regions in Ontario: south, north, central and west. Eight of the schools were from rural areas and eighteen were from urban areas. Three schools were Catholic, two were French public and twenty-one were English public. The participating educators varied in terms of what role they held and whether or not they embedded the MWM project in existing programs or initiatives.

The MWM researchers identified and recruited potential participants through existing contacts, looking for educators who wanted to take part, and who were already involved in existing collaborative environments. The sample of educators represented a “purposive and convenience sample,” as opposed to a strictly randomized or representative sample. The study is not focused on generating results that could be generalized to a whole population, but rather seeks to describe the story of what occurred when educators collaborated to evaluate select groups of MWM competencies in their schools and classrooms. This is an emergent study:13 it provides research narrative from educator experiences, rather than describing what occurred based on an existing expectation of what assessments might take place.

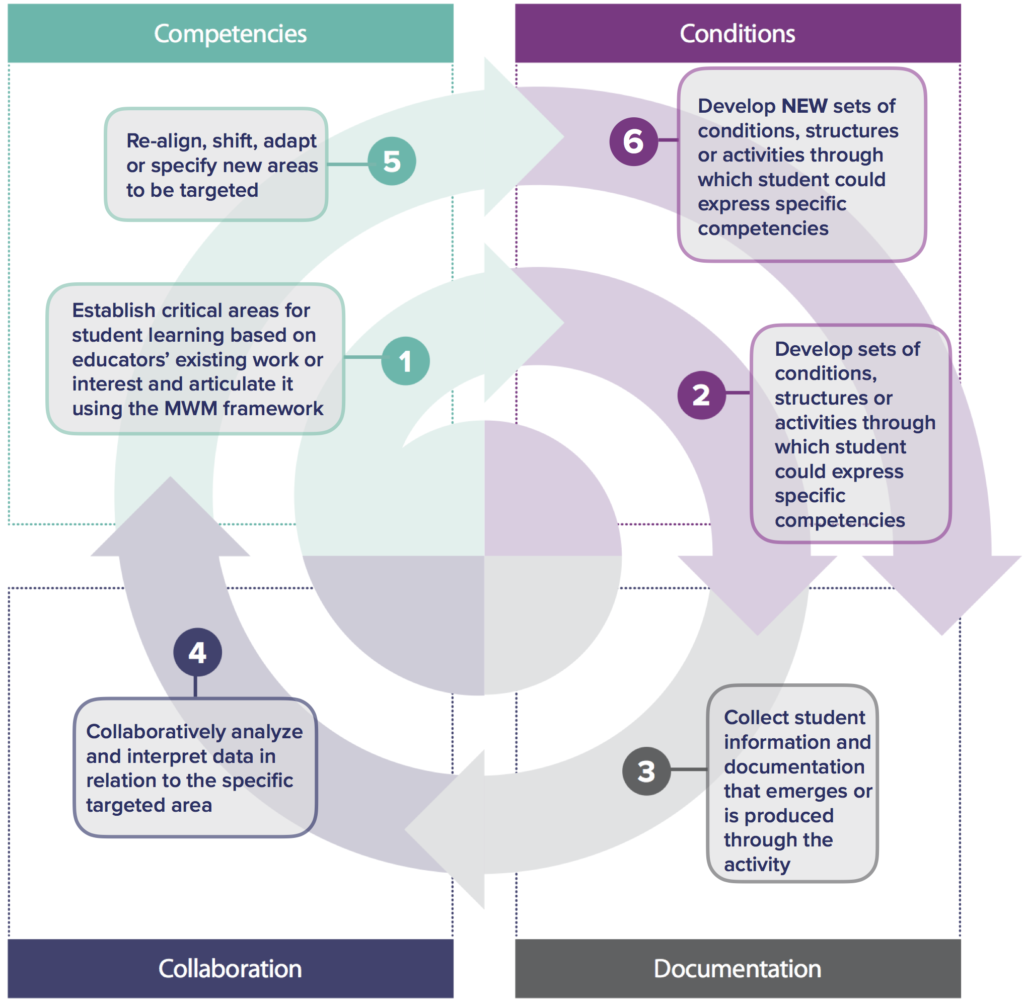

The process

While each field trial was unique in its structure, the process that participants undertook followed a fairly consistent set of phases, as represented in the diagram below.

The activities

Each school and field trial team designed and implemented a varied and personalized set of activities, which were integrated within their ongoing work, rather than designed as ‘additional’ to their existing work.

Activities ranged from math and drama collaborations, to participatory, school-wide Learning Walks. The table below articulates some specific examples.

| Examples of activities | Relevant domains |

| In a secondary school applied program, a mathematics and English teacher-team explored the roles of conditions and constraints on idea generation in mathematics and English. They set a variety of conditions through which students generated new but related ideas to the topics at hand. They observed each other’s classes and collected information from the students’ responses. |

Creativity Social-emotional learning |

| One elementary school principal in northern Ontario brought a school -wide focus on health to her community. Every morning began with an “active start,” where students kicked the day off with facilitated games and activities in the gym, rather than typical school announcements heard in their classrooms. | Health Social-emotional learning |

| A principal worked with school staff and students to co- write their elementary school’s code of conduct, which centred on three themes: respect, engagement, and responsibility. From there, teachers worked in Professional Learning Community groups to develop units and learning environments that showcased social-emotional learning competencies. | Social-emotional learning |

| A kindergarten teaching-team explored the role of play-based learning within the “imaginative” competencies area of creativity. | Creativity Social-emotional learning |

| One teacher stopped providing letter grades in her science class, instead focusing on rich descriptive feedback based on the competencies. | Social-emotional learning |

| A school coach and a teacher focused on student self-awareness and diversity of perspectives through an exploration of residential school experiences for Indigenous students. | Citizenship Social-emotional learning |

While the variation illustrated in these examples shows the broad application of the competencies to learning experiences for students in schools, it also presents challenges within the study in relation to the diversity of the contexts in which the competencies were used. The study addressed this diversity by using a common process of school and classroom assessment, which follows the Ontario Ministry of Education’s Growing Success document.14

Specifically, educators focused on formative assessment, gathering information in diverse ways, in order to provide feedback and re-establish conditions through which students can progress in specific learning tasks, competencies or concepts.15 Formative assessment of these competencies occurred both at individual levels and in collaborative teams, depending on the school or school board site. The formative assessment process was not a discrete moment of assessment; it blended into the educators’ planning and teaching. Counter to assessment as a single instant through which teachers analyze a set of data or information, this type of assessment involved adaptations in classroom or school conditions and activities in response to student learning.

The type of information gathered by participating educators was diverse, but sat in three large areas also outlined in Growing Success : observations, conversations, and student products.16 The following list is a sample of some of the evidence sources used by participating educators:

- Notes taken while observing student interactions

- Student work products

- Student self-reports

- Video recordings

- Formal and informal conversations between teachers and students

- Small-group discussion between and amongst teachers and students

The themes

Data from the field trials were collected through four means: observation, interviews, focus groups, and other artefacts (e.g. digital pictures and student work). Focus groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed, and observations were recorded in field notes and journals. All participant names are confidential, as are their schools and school boards.

Throughout the year, as the study evolved, emergent themes were used to inform new focus groups and interviews.17 A set of six preliminary themes have been identified:

| Honouring teacher professional stewardship |

| Diverse and personalized approaches to assessment |

| Dynamic nature of learning conditions and student competencies |

| Interrelationships of competencies and domains |

| A specific lexicon or “language of learning” for broad but ambiguous areas of learning |

| Broadening perspectives on where learning occurs in schools |

These preliminary themes serve as anchors to MWM’s continued partnership work with schools. They also provide critical insights into any potential jurisdictional approach to measuring broad areas of success, which, in Ontario, sit under policy umbrellas such as Student Well-Being or 21st Century Competencies.18

Honouring teacher professional stewardship

Participating educators found that the competencies resonated with work they were already focused on, or wanted to focus on, as core components of their teaching. There was some concern expressed about the notion of “measuring” students within the domains in MWM. However, the work itself, and the positioning of the work in relation to classroom and school assessment, by establishing specific opportunities for students to express specific competencies, was well received. The following excerpts were typical of the impressions that educators expressed:

| “[One teacher] commented last week [that] the competencies actually validated what she knew to be important in her heart. She works with kids who are identified [as having exceptionalities] and for the one or two students she focused on particularly, she was really looking to support their wellness… It made her feel that, ‘I always knew this is important, and now something is telling me that it’s okay to work this way; it’s not just about x, y, and z.’” – program coordinator |

| “…for me it’s always, ‘How do I make this practical?’ I believe there is a sense of urgency in education. I believe it’s so important to bring those ideas to the centre of learning in our classrooms, but also in our schools, our boards and across boards… That’s why I love being involved in this group, because we do have the capacity to share with other boards.” – school principal |

| “We have lots of frameworks, but [despite] the title, Measuring What Matters, I found it easy to put the ‘measuring’ aside. I am not quantifying, but trying to say, ‘If these are my goals that underlie what I do as a teacher, it isn’t about what [students] understand about seasonal changes in my science curriculum, it’s how they’re thinking critically and asking questions around those ideas within Science.’ I see it as a framework that gives greater purpose to what we are doing. And values the things we know are intrinsically important.” – science teacher |

The ideas in relation to learning within the MWM project are not new to education in Ontario, nor are the competencies absent from Ontario curriculum and policy.19 What is new is the formal and systematic acts of focusing on specific, concrete areas within creativity, citizenship, social emotional learning and/or physical and mental health.

The work brought energy to teachers, and resonated with things they felt were central in learning experiences, but that often did not get the same amount of attention as academic achievement. In short, doing rel-evant and integrated assessment of these areas, often with students as co -assessors, was congruent with many participants’ professional values as educators. Sergiovanni speaks of educators’ roles as stewards— focusing on the responsibility these individuals hold for the development of children. Among the participants, the experience resonated with this sense of stewardship for students.20

Diverse and personalized approaches to assessment

Educators took a range of approaches in their use of the MWM competency framework. Some took a more narrow focus, addressing one or two competencies in a single domain; others viewed their inquiry through combinations of competencies from several domain areas, e.g. citizenship, social-emotional learning, and creativity.

The critical moment for all came in the translation from a set of competencies in a domain to actual classroom and student experiences. While this “translation moment” was similar for all the participants, and the initial team-based discussions were helpful for diversifying, refining and broadening their perspectives, the methods each participant used varied widely. The individuality in what educators focused on, and how they investigated it, signals how personalized this work is. It also signals how important it is to protect non-standardized learning contexts, so that educators and their students can find the relevance of their learning experiences and processes within the sets of listed competencies and their associated domain areas.

| “I think [there are] multiple ways to engage in a relationship with these competencies: they could be my jumping off point and I start with them, or they might just come out at the very end and I lay them on [top]. It depends on… the questions I’m playing with [and] my wondering, my curiosity, leads me to connect with them…” – school district coordinator |

| “One of the things that came out of this year is the different types of evidence that were used [by teachers]. [I] wouldn’t want a limiting structure; [maybe a] show of options versus structure. [For example,] ‘You need to bring something back—here’s what it could look like: narrative, survey pre- to post-, measurable “look fors,” frequency perspective, qualitative perspective.’ It depends on what aspect of program and competencies you are focusing on.” – school principal |

| “I determined an entry point based on student emotional needs—big glaring challenges that were not addressed—elephant-in-the -room pieces no one wanted to address [such as the student’s] emotional needs. [I think] we are uncomfortable as a system in addressing [student] identity ‘issues’.” – elementary school teacher |

Dynamic nature of learning conditions and student competencies

There appears to be an inextricable and dynamic link between learning conditions and specific competencies that students express: learning conditions frame and support the expression of specific competencies and, conversely, the focus on specific competencies in relation to teaching, learning, and assessment supports teachers in exploring a greater range of possible conditions and/or learning opportunities.

In the course of the field trials, the educators established conditions in the classroom to work on a specific competency or set of competencies. Then, in reaction to the quality of responses they got from students, the educators would often reframe the conditions. This opened the door for new possibilities in the learning experience.

For example, educators found the domain of creativity was a launching point for collaborative discussion about how to teach and scaffold creativity, and for self-reflection about the conditions in their classrooms that allow students to express specific competencies within creativity. Others puzzled out the problematic nature of “risk taking,” and its connection to exposure and identity for students. Students had very different feelings about the productiveness of taking risks in classrooms, and this diversity of opinions was often associated with their identity as students. This prompted teachers to examine the conditions of the classroom that allow their students to express and understand their identities, thus encouraging risk-taking behaviour.

| “In the grade 1 and 2 classrooms, teachers were really curious about the [competencies in the] domain of creativity—specifically ‘students think flexibly’ and ‘students reflect on their own thinking process,’ and also [the condition in the Quality Learning Environment domain] ‘students are primarily driven by intrinsic motivation.’ That intrinsic motivation [condition] was of huge interest to the teachers. In our first conversation [they were] saying, ‘Is there anything I can do about that? Where does it come from? Can we actually facilitate that in the classroom? Can we change it? Does it have something to do with environment?’” – school district coordinator |

| “I guess our observations have proved… that we both think there is a need for some scaffolding in order for students to begin their creative process. We wondered how much scaffolding is too much, because sometimes if you provide too much, then that shuts down the creative process. I think one big thing that we learned was that students need the vocabulary to be able to negotiate and show, or publish, their creativity and their ideas.” – secondary school English teacher |

| “I think [using the MWM lexicon] helped us learn about the [creativity] domain, because we were forcing ourselves to notice and name those [competencies]… Why aren’t we seeing and hearing them? Why might that be? Are there conditions that we need to change or reset so that we do see more of that? When didn’t we see that? Did we see examples of creativity? What was it about that moment—that lesson—that pulled that out? How can we get more of it?” – school district coordinator |

Interrelationships of competencies and domains

From the earliest stages of establishing the domains and competencies in MWM, it was clear that there are strong interrelationships between the domains.21 These interrelationships were also evident across the work of the educators in the study.

One striking example involved work two educators did in an elementary school classroom to teach social-emotional competencies around self-awareness and the creative competency “uses metaphorical thinking” at the same time. The class used the metaphor of an iceberg to explore student personal identity and relate it to historical perspectives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. As they moved from their diverse peer and personal notions of identity to their study of what Indigenous identities and perspectives might be, given First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples’ historical, cultural and political realities in Canada, students further developed competencies in the citizenship and social-emotional learning domain.

| “We wanted this whole discussion and thinking of identity to go beyond self and local communities. Our inquiries sat hard on First Nations. It’s interesting that as we explored First Nations’ history and current issues, the students began to talk about residential schools and foster children who are Aboriginal, and then make sense of them as individual children and their loss of language. …interweaving notions between their own understanding of identity and the book [they read]. They wondered how the main characters were also [like them] struggling with identity and what [the characters’] ‘Iceberg’ might look like and what their own ‘Iceberg’ looked [like]. That was amazing. The intra[-personal] connections really deepened their thinking. This is a quote from one student talking about identity [reading from her observation notes], ‘I think we’ve been talking about identity, because we all have identity. We’re learning that some people have parts of themselves that they want to keep hidden and some people have the exact same parts that they want to reveal; reveal it all at the top of the Iceberg. The things that they want to reveal could be something like talent. Some people have a talent that they might hide all the way out at the bottom of their Iceberg.'” -elementary school teacher, program coordinator, and student |

The way that these competencies bled into each other within the learning experience was typical amongst the educators in the case. It illustrates the problematic nature of translating discrete, rational frameworks like MWM, into complex experiences. It also points to the importance of creating policy and institutional space to support professional autonomy, reflection, and exploration.

A specific lexicon or “language of learning” for broad but ambiguous areas of learning

Participants in the study noted how helpful it was to have a specific, common language in which to bind these complex areas of learning. The competencies gave educators clear pathways into actions and planning in classrooms. Competencies enabled meaningful and critical dialogue amongst educator teams within schools and across a wide array of contexts.

The specific language of the competencies created opportunities for educators to communicate with each other, to generate new conditions, and to make different meanings out of everyday classroom experience. Two different educators in the case share this as they reflect on their use of the competencies:

| “…the domains and competencies really accelerated conversations [among educators]. The domains are the things that inevitably double up when we study the student learning experience, whatever the context is. With a lot of people context is the numeracy. Even though that might be where we start, [other] things come out like social-emotional learning and creativity.” – program coordinator |

| “I sensed that [teachers on this team] felt that creativity was sort of this nebulous concept and [they thought,] ‘What does it look like in areas other than art?’ Then I was at their school with them a couple of weeks ago and it was interesting to hear how their thinking had evolved; that actually it’s not just this nebulous thing, it lives in so many different places and spaces and [the specific competencies] helped them name and unpack what it looked like and actually make connections to the curriculum.” – program coordinator |

In one field trial, the specificity of the language in the competencies provided common ground for a kindergarten teacher and three secondary school teachers (each teaching different subjects) to reflect together on their practices and their assumptions about their students’ capacities. Despite the differences in their subjects and the ages of their students, the teachers were able to dig deeply into the sometimes nebulous idea of creativity, by focusing on a single creative competency: “working without an end goal in mind.” The specificity of the language allowed the teachers to discuss how they would structure learning opportunities to develop this competency.

These examples illustrate the value of having concrete, specific language available to support educators working together within these broad areas of learning, in much the same way as they would discuss specific skills when working on mathematics or reading. The language allowed for deeper entry points in relation to discussions of pedagogy and learning theory. It allowed for cross-contextual understanding and dissonance, and provided a concrete means through which classroom micro-adjustments could be planned, documented, analyzed, and discussed.

Broadening perspectives on where learning occurs in schools

A number of schools in the study explored student experiences outside of the classroom. Here, perspectives on where learning occurs and what constitutes a learning experience for students broadened from specific, situated moments in scheduled classroom times to student experiences throughout the school day. One principal led her staff in shifting the school hallways and stairwells from age-segregated corridors to places where students from all grades represented their learning in relation to the domains (creativity, social-emotional learning, citizenship, and health). She states:

| “What we’ve done is we’ve been working towards designating and labeling [different] school spaces [with each MWM domain]. Our decision was to take each area and link them. We’re going to use our staircases to link them. The primary [students] took on creativity. The intermediates really wanted social-emotional. The juniors wanted citizenship, and then right in front of the gym we have our health component. We’re trying to break down barriers to create a sense of community in our school. When you go down to creativity we will have examples from the intermediate [students’ work] in the primary spaces. We’re breaking down those paradigms of, ‘This is kindergarten alley and this kindergarten work.’ We want the kids to connect, but we also want the teachers to connect.” – school principal |

The themes emerging from the field trials represent preliminary understandings. They are considerations from the mid-point of an exploration of how schools and educators approached broad areas of learning, what they did within their schools to provide opportunities for students to express the competencies in the MWM domains, and their general impressions of assessment in relation these domain areas. The study should be considered as an example that informs how we might think about broad areas of learning and success in relation to planning, teaching, and assessment within schools. It provides insights into both the potential of school and classroom assessment of these competencies and the problems and complexity of tackling this issue.

The preliminary findings suggest that a jurisdictional measurement and reporting system which offers good information about broad, essential areas of student success cannot be realized without a deep understanding of how to support local, specific, school-based experiences in assessment that are collaborative, varied, contextually dependent, and responsive to student needs.

| Activities | Reports |

| Phase 1 – 2013–14: Engaging the public and the experts | |

|

Broader Measures of Success: Measuring what matters in education |

| Phase 1 Report: Beyond the three Rs | |

| Phase 2 – 2014–15: Defining domains and competencies | |

|

Domain papers:

|

| What Matters in French Language Schools | |

| Phase 2 Report: 2014–15 From Theory to Practice | |

| 2015/16: Testing competencies; developing conceptual model | |

|

What Matters in Indigenous Education |

| Phase 3: 2015–16 Progress Report |

- These are examples taken from the UN’s Sustainable Developmental Goals, as well as challenges in world economic growth identified by the IMF’s January report.

- These competency examples come from the Government of Canada’s website. Communication and collaboration are required to develop the reports and recommendations that Canada commits to produce from “multi-stakeholder engagement and partnerships”. Flexible thinking and information literacy are required to “craft new and innovative policies and mechanisms” to progress society and understand when goals and targets have been reached using data.

- Some examples of these are Alberta Education 2, Fullan, Ontario Ministry of Education (“21st Century Competencies”), and Winthrop and McGivney.

- One example of this reaction took place in September 2016, when Ontario committed $60 million to the Renewed Math Strategy in response to low math scores on the Education Quality and Accountability Office test from spring 2015. The resultant Policy/Program Memorandum (PPM 160) is available online.

- See Gallagher-MacKay and Kidder.

- For the complete report on phase one, see People for Education.

- For the complete report on phase two, see Cameron, et al.

- For more information about the creativity domain, please see Upitis.

- For more information about the citizenship domain, please see Sears.

- For more information about the health domain, please see Ferguson and Powers.

- For more information about the social-emotional learning domain, please see Shanker.

- For more information about the quality learning environments domain, please see Bascia.

- Emergent design involves data collection and analysis procedures that can evolve over the course of a research project in response to what is learned in the earlier parts of the study. In particular, if the research questions and goals change in response to new information and insights, then the research design may need to change accordingly. This flexible approach to data collection and analysis allows for ongoing changes in the research design as a function of both what has been learned so far and the further goals of the study. Within the broader framework of qualitative research, emergent design procedures are closely associated with the broad goal of induction because success in generating theories and hypotheses often depends on a flexible use of research methods. For more information see Morgan.

- For more information see Ontario Ministry of Education, “Growing Success.”

- For more information about assessment practices, see Black and Wiliam, especially pages 142-6.

- See Ontario Ministry of Education, “Growing Success” 39.

- This is similar to the “constant comparative method” outlined in the works of Glaser, and Strauss and Corbin.

- See Ontario Ministry of Education, “21st Century Competencies” or Ontario Ministry of Education, “Ontario’s Well-Being Strategy for Education.”

- For a review of curriculum and policy, see Cameron, et al. 5-8.

- For more information, see Sergiovanni.

- For more information, see Cameron, et al. 4.

Alberta Education. Framework for Student Learning: Competencies for Engaged Thinkers and Ethical Citizens with an Entrepreneurial Spirit. Government of Alberta, 2011. Alberta Ministry of Education. Web.

Bascia, Nina. “The School Context Model: How School Environments Shape Students’ Opportunities to Learn.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto, 8 Nov. 2014. People for Education. Web.

Black, Paul, and Wiliam, Dylan. “Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment.” Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 80, no. 2, Oct. 1998, pp. 139-48.

Cameron, Dave et al. “Measuring What Matters 2014-15: Moving from Theory to Practice.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 3, 2015. People for Education. Web.

Ferguson, Bruce, and Powers, Keith. “Broader Measures of Success: Physical and Mental Health in Schools.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto, 8 Nov. 2014. People for Education. Web.

Fullan, Michael. Great to Excellent: Launching the next stage of Ontario’s education agenda. Michael Fullan: Motion Leadership, 2013. Michael Fullan. Web.

Gallagher-MacKay, Kelly, and Kidder, Annie. “Broader Measures of Success: Measuring What Matters in Education.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto, June, 2013. People for Education. Web.

Glaser, Barney. Theoretical Sensitivity. Mill Valley Sociology Press, 1978.

Government of Canada. “Summary Report of the Discussion on the Government of Canada’s Post-2015 Development Priorities.” Global Affairs Canada. 12 May 2015. Accessed 4 Nov. 2016.

Morgan, David L. “Emergent Design.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, edited by Lisa M. Given et al., SAGE, 2008, pp. 245-8.

Ontario Ministry of Education. Growing Success: Assessment, Evaluation, and Reporting in Ontario Schools. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2010. Ministry of Education. Web.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 21st Century Competencies; Foundation Document for Discussion. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016. Ministry of Education. Web.

Ontario Ministry of Education. “Fact Sheet for Parents.” Ontario’s Well-Being Strategy for Education; Fact Sheet for Parents. 2016. Accessed 4 Nov. 2016.

Ontario Ministry of Education. “Ontario Providing More Math Supports for Students and Families.” Newsroom: News Releases. 21 Sep. 2016. Accessed 4 Nov. 2016.

People for Education. “Measuring What Matters: Beyond the 3 ‘R’s’.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto, 8 Nov. 2014. People for Education. Web.

Sears, Alan. “Measuring What Matters: Citizenship Domain.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto, 8 Nov. 2014. People for Education. Web.

Sergiovanni, Thomas J. “Leadership as Stewardship.” Rethinking Leadership: A Collection of Articles. Corwin, 2007, pp. 49-60.

Shanker, Stuart. “Broader Measures of Success: Social/Emotional Learning.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto, 8 Nov. 2014. People for Education. Web.

Strauss, Anselm, and Corbin, Juliet. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, Sage, 1990.

The International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: Update. Washington, 16 Jan. 2016. International Monetary Fund. Web.

The United Nations. Sustainable Developmental Goals. 25 Sep. 2015. Accessed 4 Nov. 2016.

Upitis, Rena. “Creativity: The State of the Domain.” Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto, 8 Nov. 2014. People for Education. Web.

Winthrop, Rebecca, and McGivney, Eileen. Skills for a Changing World: Advancing Quality Learning for Vibrant Societies. Washington, D.C., The Brooking Institution, May 2016. Brookings. Web.