Nina Bascia from Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto highlights the interactive and dynamic environments in schools that support and shape rich learning experiences for students and educators.

Schools are complex, dynamic systems that influence students’ academic, affective, social, and behavioral learning (Crick, Green, Barr, Shafi & Peng, 2013; Gu & Johansson, 2013). Phelan, Davidson and Yu’s “Students at the Center” study (1996) demonstrated that classroom and school contexts – the operating environment within schools – affect the quality and degree of students’ learning and potential outcomes. School organizational and classroom practices can influence the amount and depth of students’ opportunities to use the educational system as a stepping stone to further education, productive work experiences, and ultimately, a contributing factor toward meaningful and satisfying adult lives within a democratic society (Center for Social and Emotional Education, 2009).

The Measuring What Matters initiative is based on the contention that student and school success cannot be defined solely by the measurement of student performance in literacy and numeracy, the accumulation of subject credits, or graduation rates (http://www.peopleforeducation.ca/measuring-what-matters/ wp-content/uploads/2013/10/P4E-MWM-full-report-2013.pdf ).

Student success is actually a construct of a broad array of skills, experiences and outcomes across a number of different domains, from social-emotional learning and health, to creative, critical thinking and qualities of democratic citizenship. All are central to student success at school and in their future lives as adults (see Shanker, 2014; Ferguson, 2014; Sears, 2014; Upitis, 2014). The papers on creativity, social and emotional learning, citizenship, and health have all pointed to the importance of quality learning environments in fostering a range of desirable student outcomes. For example, Shankar notes that: “Efforts to promote safe, caring and inclusive school environments, together with anti-bullying and restorative justice practices, are having an important impact on students’ social awareness and interpersonal relationships.” Ferguson argues that: “The whole school environment, including its individuals and their relationships, the physical and social environment and ethos, community connections and partnerships, and policies, are seen as important areas for action if a school is to promote health.”

It is widely understood that schools do not have sole responsibility for enabling all these learning outcomes for students. Home and community contexts contribute significantly to students’ schooling experiences and their learning outcomes (Thrupp and Lupton, 2013). But the quality of practices both inside the classroom and across the school play a critical role in providing learning opportunities and developing environments in which students can flourish (Crick, et al., 2013).

This paper provides a framework for studying the influence of school environments on student learning. The first section of the paper examines theoretical and research perspectives in conceptualizing school organizational practices. The second section describes the roles, processes and opportunities that have been linked to students’ academic, social and emotional development. The third section considers the measurement of school environment.

The school environment as a basis for student learning has been a focus of research interest for decades, and developing school settings that positively influence student learning has been a subject of policy and practice that has grown in intensity over time. It is worth looking at the recent past to understand some of the evolution of research into the impact of the quality of the learning environment on student success.

In 1966, the publication of the widely cited Coleman Report in the United States raised questions about the relationship between the qualities of the school environment and students’ demographic background in regard to educational outcomes for students. During the 1960s and 1970s, the prevailing belief was that the strongest influences on student academic success were factors that students “brought with them” to school such as socioeconomic status and parental support for education, rather than school features and processes. This notion – that students have different amounts of “social capital” that affect their chances for success – is attributed to Coleman and a few other later sociologists (Portis, 1998).

Moving from the 1970s into the 1980s, attention shifted away from factors outside of the school toward what Sackney (2007) calls more “hopeful” research that – while never denying the impact of students’ socio-economic status – focused on school practices and organizational structures. School organizational research in this era sought to identify school features that could be altered by educators to make a positive difference in student learning (Sackney, 2007).

The various factors that make up the school as an organization, and the influence that these factors have on classroom teaching and learning, have been conceptualized in the literature in a number of ways. School organizational research has examined the qualities and characteristics of school life (Pickeral, Evans, Hughes & Hutchison, 2009) and their possible impact on students’ academic success (Hatte, 2010; Voight, Austin, & Hanson, 2013). Researchers have also investigated such factors as teachers’ and students’ wellbeing (Haar, Nielsen, Hansen, & Jakobsen, 2005; Russ et al., 2007), teacher commitment (Collie, Shapka, & Perry, 2011), teacher efficacy ( Guo & Higgens-D’Allessandro, 2011), teachers’ professional learning (Cochran Smith and Lytle; Little, 1993), micro-political practices and power relations within schools (Ball, 1987) bullying prevention (Cohen & Freiberg, 2013), school leadership (Leithwood, Louis, Anderson and Wahlstrom, 2004) and school reform or change (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010 and Hargreaves and Shirley, 2009).

School climate

One of the key perspectives on schools’ impact on student learning is known as school climate research. While there is no universally agreed-upon definition of school climate, it includes a range of school factors that broadly shape students’ school experiences. As many provinces/states and districts focus efforts on promoting and measuring various aspects of schools, a variety of definitions and frameworks have been developed (see for example Cohen, McCabe, Michelli, & Pickeral, 2009; National School Climate Council, 2007; and Pickeral, Evans, Hughes & Hutchison, 2009). Drawing on these frameworks, school climate research can be broadly organized into four realms:

- School safety (physical safety, social-emotional safety, tolerance, discipline policies);

- Interpersonal relationships (respect for diversity, engagement, social support, school connectedness, shared decision-making, administrative support, community involvement);

- Teaching and learning practices (opportunities for teachers to experiment and learn, support for professional collaboration, instruction and assessment policies, opportunities for students’ social, emotional, ethical, intellectual and civic learning,); and

- Organizational structures (rules and norms, infrastructure, resources, supplies, scheduling).

The school climate framework conceptualizes schools as consisting of particular variables, and in many cases associates these variables with student academic achievement through statistical analysis (Hattie, 2010). It is important, however to understand the dynamic and interactive day-to-day reality of schools, for example, how organizational characteristics such as administrative leadership work in tandem with other school factors, such as teacher professional learning opportunities to have an impact on rich opportunities for teaching and learning. Deakin Crick and her colleagues (Deakin Crick, Green, Barr, Shafi & Peng, 2013) note that “A school’s core processes of student learning and achievement are themselves complex and dynamic and cannot be reduced to, or described by, a single variable” (p. 21).

Failing to attend to this interactivity of various school characteristics can lead to the use of a checklist of items that schools may strive to incorporate with less attention paid to the relevance of those items to their particular milieu (Mintrop & Trujillo, 2007). But the use of school checklists to drive school improvement does not generally help explain why we see particular results in some schools and not in others. As Talbert and McLaughin (1999) argue, particular conditions in schools combine or interact in different ways to generate differences across schools. Finally, while the characteristics associated with school climate are often described or defined distinctly, in practice these characteristics tend to lack sharp definition (Porter, 1991).

Process and context

Partially in response to the limitations of methods that can result in a “checklist” approach, researchers have proposed the development of what are called process or context indicators that allow us to trace how schools provide educational opportunities (Porter, 1991). Oakes (1989) characterizes process indicators as focusing on necessary conditions for quality teaching and learning. Kim (2012) calls the utilization of process indicators a way to understand the “‘what’s- going-on’ of schools”. The dynamic, integrated use of a wide variety of school indicators can provide rich information on the quality of resources, people and activities that shape children’s day-to-day experiences. (Boyd, 1992; Oakes, 1989; Scheerens, 2011; Talbert & McLaughlin, 1999)

The interactivity of a range of school factors within school learning environments can be seen when we examine within-school differences across classrooms, academic subjects, and other program distinctions. Student access to knowledge and expectations for skills development, classroom teaching quality, and general classroom learning climates can vary widely within a school (Oakes, 1985). Studies such as the Teaching for Understanding study conducted in high schools in the 1990s (Cohen, McLaughlin & Talbert, 1993) demonstrated not only differences across classrooms in students’ opportunities to learn, but even differences in learning opportunities for students of the same teacher from one class period to another. In addition, the programs or courses designed for different ability streams create markedly different expectations and opportunities for groups of students in the same school (e.g. Oakes, 1985). These differences result from the interactive and dynamic nature of school context—contextual factors function differently for different members of the school community. For example, teachers’ perceptions of school context tend to be more sensitive to classroom-level factors such as classroom management and student behavioural issues, while students tend to be more sensitive to school-level factors such as student-staff relationships and principal turnover (Mitchell, Bradshaw & Leaf, 2010). Other research has demonstrated that some students perceive teacher-student relationships as the most important dimension of the school context, while other students emphasize teacher fairness and the importance of moral order (Slaughter-Defoe & Carlson, 1996). Higgins- D’Alessandro & Sakwarawid (2011) have shown that students with special needs do not benefit from the positive features of school context unless they feel included and respected by other students.

School context research has also revealed differences between schools in interactions among school level factors such as principal and teacher leadership, human and material resources, classroom practices, professional teaching conditions, and teacher community (Bascia, 1994, 1996; Bascia & Rottmann, 2011; see Talbert & McLaughlin, 1999). Oakes states:

School resources, structures, and culture are not discrete school characteristics; they interact. [For example,] although the development of an effective school context cannot be attributed to the level of resources provided to it, neither can it be accurately separated from it. The presence or absence of resources (e.g., nonteaching time) can make cultural norms (e.g., collegial work) easy or nearly impossible to establish. Similarly, particular structures (e.g., many rigorous course offerings) will interact with and reinforce particular elements of the school culture (e.g., a commitment to student learning). . . . Ideally, school-level indicators will provide descriptive information about important combinations of these school characteristics. The challenge is to construct indicators that will inform policy makers and educators about how schools use their resources to establish policies, organizational structures, and cultures that promote high-quality teaching and learning (Oakes, 1989, p. 192-3).

Oakes’s argument is extremely relevant in considering the variety of learning domains (e.g. health, citizenship, creativity) emphasized by the Measuring What Matters initiative for the following reasons:

- The domains are complementary. They are interactive, not discrete subject/skills for students. For example, when Upitis (2014) argues for qualities of experimentation and risk, she is also touching on Shanker’s (2014) points about student and teacher self efficacy as well as students’ ability to develop resilience.

- Like literacy and numeracy, each domain exists within a wide array of subjects and school practices, from extra-curricular opportunities to subject areas like science, arts and geography.

- Measuring discrete indicators in isolation from each other will and often does serve to narrow and limit what is measured

and what is taught, potentially constraining opportunities for schools, teachers and students to exhibit critical, creative moments in learning and teaching (Gilborn, 2001; Cameron, 2010).

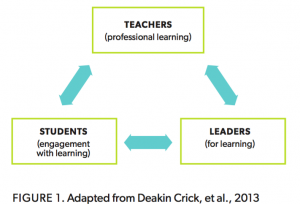

The school context concept characterizes schools as dynamic systems that influence a broad range of dimensions of student learning, including affective, social, behavioral as well as academic domains (Deakin Crick, et al., 2013; Gu & Johansson, 2013) – the very domains in which the Measuring What Matters initiative is interested. In Deakin Crick et al.’s conceptual model of the school context, the key process in schools is learning, and the key actors in school are leaders (both administrators and teachers who “lead for learning”), teachers (especially teachers’ professional learning) as well as students (engagement in learning and achievement).

The school context concept characterizes schools as dynamic systems that influence a broad range of dimensions of student learning, including affective, social, behavioral as well as academic domains (Deakin Crick, et al., 2013; Gu & Johansson, 2013) – the very domains in which the Measuring What Matters initiative is interested. In Deakin Crick et al.’s conceptual model of the school context, the key process in schools is learning, and the key actors in school are leaders (both administrators and teachers who “lead for learning”), teachers (especially teachers’ professional learning) as well as students (engagement in learning and achievement).

In the school context model, these three groups of actors are conceptualized

as interrelated “subsystems”. For example, the relationship between leadership and student learning has been explored in several studies, which concluded

that successful school leaders – based on measures of higher student engagement and attainment – prioritized staff motivation and commitment, teaching and learning practices and developing teachers’ capacities for leadership (Bottery, 2004; Gunter, 2001; National College for School Leadership, 2004, 2010). Numerous studies demonstrate that teachers’ professional learning that is embedded in professional work has a positive influence on classroom practices and student learning (e.g., Cohen & Hill, 2001; Day & Leith, 2007; Garet, et al., 2001).

The research suggests that student engagement with learning is both a necessary condition for, and a consequence of, deep learning (Deakin Crick, et al., 2013). As mentioned earlier, Phelan, Davidson and Yu’s Students at the Center study (1996) demonstrated that the operating environment within classrooms and schools affect the quality and degree of students’ attention and their interest and engagement with school, as well as their ability to transition smoothly from home to school, from one classroom to the next and between classrooms and other parts of the school; and their responsiveness to a variety of teachers and other adults. Among other things, these capacities in turn affect their ability to develop the resilience that will help enable them to adapt to stress and adversity as they encounter diverse situations in their adult lives.

Learning and teaching settings that contribute to improved student outcomes

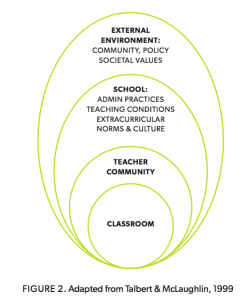

Talbert and McLaughlin (1999) provide a second but complementary conceptualization of school context. While the Deakin Crick et al. model emphasizes “subsystems” of students, teachers and leaders, the Talbert and McLaughlin model identifies sites of influence on teaching and learning. The classroom core of their “nested context” model (see Figure 2) is the primary school setting, the locus of regular and sustained interactions among students and teachers around curriculum (EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2005; see also Porter, 1991). A nested or embedded school context framework refers to complex processes that encourage powerful learning and feedback. In this model, how a student learns depends in part on the larger system in which they learn (Deakin Crick, et al., 2013). In developing contextualized accounts, learners and their environments (students, teachers, leaders and organizations) are conceptualized as parts of a single whole. As such, it is important to focus on a range of processes and variables in schools with a systems perspective to understand the whole, the parts and how they interact (Boyd, 1992; Sarason, 1990). Because of this complexity, the influence of single (independent) factors may not have the same influence (or the same degree of influence) in all schools. A nested context framework creates a dynamic blueprint for school improvement where no uniform or single measure of success can define the entire organizational performance of a school. Consider the figure below:

In the Talbert and McLaughlin framework, classrooms as settings for learning and teaching are “nested” within teacher communities, which are nested within schools, which are nested within the wider community. This means that what occurs in beyond the classroom influences (and is influenced by) what occurs within the classroom.

The classroom

The classroom itself is the locus of regular and sustained interactions among students and teachers around curriculum (EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2005; Talbert & McLaughlin, 1999).If the classroom is at the heart of students’ opportunities to learn, the quality of teachers’ instructional practices are of paramount importance (Hattie, 2010).

Quality instructional practices include linking learning to factors that are important in students’ lives. Applying knowledge to real life situations makes content easier to understand and demonstrates its relevance to students’ lives (Taylor & Mulhall, 1997; Crowley, 2003). Using a variety of different teaching methods (e.g., direct instruction, problem-based learning, cooperative learning, advance organizers, experiential learning, small group and whole class discussions, etc.) and making adjustments for different learning styles (e.g., visual, verbal, physical, logical, social, solitary) provides opportunities for all students to learn effectively (Hattie, 2009; Orlich, Harder, Callahan, Trevisan, Brown & Miller, 2012). Maintaining and communicating high expectations for all students is a critical feature of classrooms that support effective learning—all students need challenging subject matter to remain engaged in learning (Frome, 2001; Hallinan, 2002; Jussim & Eccles, 1992).

Using formative and summative assessments in a systematic manner provides valuable information to students and significantly improves learning and achievement (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986; Black & Wiliam, 1998). Setting objectives and providing regular feedback (including praise) on student progress toward achieving those objectives helps to keep students motivated and on track (Marzano, Pickering & Pollock, 2001). Providing opportunities for participation in classroom activities also maintains student engagement in learning (Parsons, Nuland & Parsons, 2014), as does helping students to draw connections between different disciplines (Dunleavy & Milton, 2009).

The classroom context includes much more than the teacher’s instructional practices. The quality of life in the classroom is of great importance to students (Thorp, Burden & Fraser, 1994; Watkins, 2005). Creating an atmosphere in which diversity is respected and individual differences are appreciated contributes to student success and resilience (Bondy, Ross, Gallingane & Hambacher, 2007). Treating social and emotional learning as a valuable and teachable subject contributes to a positive classroom context and supports academic learning in other subjects (Zins, 2004). Fostering positive relationships within the classroom contributes to substantial improvements in student outcomes (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Fraser & Walberg, 2005), as do systematic classroom management strategies and non-coercive approaches to discipline (Freiberg, Huzines & Templeton, 2009; Marzano & Marzano, 2003).

These different aspects of the classroom context do not function independently: they interact in many different ways as part of a dynamic system. It is clear that teachers will have difficulties deploying any of their instructional strategies if their classroom management strategies have failed. Equally, students will be reluctant to participate in classroom activities if they are teased for their individual differences, but there are also many less obvious interactions. For example, praise can help to keep students on-task and engaged with learning, but it also helps to build close relationships between students and teachers (Brophy, 1981), which in turn contributes to student learning. Conversely, in classrooms with poor student-student relationships, praise from the teacher can lead to teasing and bullying of the student who received the praise (Burnett, 2001).

Teacher Communities

Just as classrooms are “nested” within schools, so often are groups of teachers who identify themselves in relation to the work they do in common and who share a set of norms, values and perspectives (Bascia, 1994; Little, 1992; Talbert & McLaughlin, 1999). While there is no doubt that instruction and classroom environments have the greatest impact on student learning (Louis, Dretzke, Wahlstrom, 2010), teacher communities can affect instruction and other aspects of the classroom, and thereby can exert an indirect influence on student outcomes.

Teacher communities have a strongly positive impact on student outcomes

when teachers participate in professional learning communities (PLCs). The norms and practices within a given professional community will dictate teachers’ opportunities to brainstorm teaching solutions with other teachers, to share teaching strategies and thus to broaden their pedagogical repertoires. PLCs are based on the assumption that the day-to-day experiences of teachers generate rich knowledge about student learning, and that knowledge is best understood through critical reflection with others who share the same experiences (Buysse, Sparkman & Wesley, 2003). The ways teachers talk among themselves about students’ abilities and capacities to learn can shape how individual teachers provide and distribute learning opportunities to students in their classrooms.

PLCs that maintain a clear and consistent focus on student learning; engage extensively in reflective dialogue about curriculum, instruction, and student development; use a variety of classroom based data to inform and refine their work; and have access to new pedagogic ideas and professional development opportunities, have positive impacts on instructional practices and student learning (Vescio, Ross & Adams, 2008). Effective PLCs require positive and collegial relationships among teachers. As well, in order to participate effectively in PLCs, teachers need non-teaching professional time and opportunities for common academic planning with other teachers.

Teachers’ working conditions can also shape student learning. School level factors that repeatedly have been identified by teachers as critical to the quality of their work include manageable workload and class size; time available for professional, non-teaching work; resource adequacy; collegiality and stimulating professional interactions; opportunities to learn and improve; support for professional risk-taking and experimentation; ability to influence school decisions; and congruence between individual and organizational goals (Bascia & Rottmann, 2011; Leithwood, 2010; Louis, 1992; McLaughlin & Yee, 1988; Yee, 1990). Each of these factors is directly relevant to students’ opportunities to learn.

The School

The whole school experience is also a setting for student learning (Macbeath & McGlynn, 2002). Teacher communities are nested within schools, and a number of school features affect the classroom—and, ultimately, student outcomes— either indirectly through their effects on teacher communities or more directly through their impact on the classroom.

Leadership is an important feature of the school environment (Waters, Marzano & McNulty, 2003). School leaders (i.e., principals and teacher-leaders) contribute to positive school environments in two main fashions: by identifying and articulating a vision that inspires staff and students to reach for ambitious goals and continually pursue new learning; and by ensuring that teachers have the resources they need to teach well (Leithwood & Riehl, 2003).

But school principals are not the only role in the school that practices leadership. In Hallinger’s review of research on notions of instructional leadership across the past 30 years, he identifies four key areas of school leadership that makes a difference for student learning (Hallinger, 2009):

- Leadership is not limited to the school principal or formal leadership roles. It is distributed. Leadership is shared across the school’s staff, amongst teachers.

- Leadership practice must be adaptive to the needs of the school’s particular context.

- Leadership models the core purpose of schools, ongoing learning for all stakeholders.

- Leadership is integrated as an important factor amongst many within the school’s pursuit of systemic improvement or development.

Seen through this lens, principals can foster a culture in which teacher professionalism is respected—that is, teachers feel responsible for their students’ learning outcomes and they feel trusted to use their professional knowledge and judgment to ensure successful learning outcomes. Principals support teacher communities by providing instructional leadership, which has an impact on teacher communities and classroom practices (Hallinger, 2003). For example, principals can initiate, participate and support the development of professional learning communities (e.g., by providing release time and scheduling that allows teachers to work collaboratively). They can use these learning communities to inform school decisions. Thus, authorizing the teacher community as a lead structure that informs school strategy. Shared decision-making practices also reinforce principals’ respect for teacher professionalism (Rice & Schneider, 1994). Principals provide opportunities for professional development and communicate an expectation that teachers will take responsibility for directing their own professional development.

Students learn in a variety of school locations beyond the classroom: extra- curricular activities such as clubs and sports are also sites of students’ informal learning, where they come in contact and interact with teachers and peers and develop skills that complement their academic work (Phelan, Davidson & Yu, 1996). For example, sports activities can foster teamwork, boost students’ overall confidence within a school setting, and allow students to engage in different kinds of relationships with adults around physical skills development. Students who participate in play production have opportunities to develop their social and emotional intelligence as they explore different points of view beyond their own through the embodiment of different roles on stage.

The school context can also shape student learning through the “hidden curriculum.” The hidden curriculum refers to messages students receive from structures of authority and values implicit in the operations of school. Students receive such messages from, for example, the system of rewards, staffing patterns, the availability of various subjects and extra-curricular learning opportunities, and the nature and quality of resources made available to students (Connell, 1996; Werner, 1991). These messages inform students of what is valued in their school environment. In school environments that support successful student outcomes, academic press—the degree to which the school environment presses for student achievement on a school-wide basis (Murphy, Weil, Hallinger & Mitman, 1982)—is a large component of the hidden curriculum. Academic press includes high expectations among teachers as well as school policies, practices, expectations, norms, and rewards that favour academic achievement. Principals and teachers can contribute to building academic press through school policies and reward systems and by consistently communicating that success in academic work is expected and attainable.

Feeling physically safe—for both students and staff—is another component of school environments that support successful student outcomes (Cohen, McCabe, Michelli & Pickeral, 2009). Principals and the whole school staff contribute to a safe school environment by clearly communicating rules for behavior and responding to infractions (particularly bullying and violence) in a clear and consistent manner. Feeling socially and emotionally safe is equally important and often rests on a clearly articulated vision of the school as a community that cares for its members and respects and appreciates diversity and individual differences.

Finally, the physical structure of the school forms a part of the school environment. Clean, well-maintained and appropriately resourced facilities have been linked to higher achievement scores, fewer disciplinary incidents, better attendance, and more positive attitudes toward learning among students (McGuffey, 1982; Weinstein, 1979)

The External Environment

Schools are nested within their external environment, which includes parents, the community in which they are situated, the economic conditions present in those communities and the values espoused by that community; curriculum standards, achievement expectations, programmatic requirements, and other policy directives; and other social agencies that serve children. The external environment can contribute to successful student outcomes and build resilience among students by improving the community’s economy and employment opportunities, through caring and supportive adult relationships, opportunities for meaningful student participation in their communities, and high parent expectations regarding student learning (Bernard, 1997; Bryan, 2005; Wang, Haertel & Walberg, 1998).

Parental engagement in their children’s education can also contribute to successful student outcomes. Students with parents who have high expectations and express support for the schools their children attend and the teachers working in those schools tend to: earn higher grades, enroll in more difficult courses, maintain regular attendance, have better social and emotional skills, adapt well to school, complete high school and pursue post-secondary studies (Henderson & Mapp, 2002). Schools can support parental involvement by scheduling parent-teacher meetings, sending materials home, and communicating with parents about student progress. A culture of respect and appreciation for diversity within the school can also support parental involvement.

Synthesis: The critical components of positive/supporting school contexts and how they interact

The preceding sections of this paper have identified what have been characterized as key people, processes and system layers within the school context research. For Deakin Crick and her colleagues (2013), schools are dynamic, living systems where the critical activity is learning among leaders, teachers and students. In Talbert and McLaughlin’s (1999) context model, students’ school realities are inherently multilevel (including classroom, teacher communities, schools, and the context outside of schools). In both school context models, classrooms are of central importance because this is where teachers and students focus on learning. To a large extent, teachers’ classroom practices mediate the effects of the teacher community and school layers of the environment on student outcomes (Hallinger & Heck, 1996; Leithwood, Louis, Anderson & Wahlsttom, 2004; Vescio, Ross & Adams, 2008). But many of the relationships between features of the environment are more complex. For example, the disciplinary climate of the school can affect students’ behavior in the classroom, which has an impact on student learning and an impact on teacher practices in the classroom (e.g., less time spent on classroom management and more time spent on instruction). Establishing a culture of caring and respect at the school level can have an impact on students’ openness to participation in classroom activities, which can also have an impact on teacher practices.

Researchers use the term “process indicators” interchangeably with “context indicators” to allow us to trace how schools provide educational opportunities to students (Boyd, 1992; Oakes, 1989; Porter, 1991; Scheerens, 2011; Talbert & McLaughlin, 1999). According to Oakes (1989), “Ideally, school-level indicators

[should] provide descriptive information about important combinations of these school characteristics. The challenge is to construct indicators that will inform policy makers and educators about how schools use their resources to establish policies, organizational structures, and cultures that promote high-quality teaching and learning.”

The Talbert and McGlaughlin (1999) model provides a useful framework for conceptualizing the school context as consisting nested layers of influence on student learning. In developing strategies to measure the school environment,

it is important to consider features of the school environment within each of those layers and to be attentive to the interactions between those features in the dynamic system of the school. The research to date suggests that the following features should be included in measures of school environment:

Classroom features:

- Learning is linked to students’ lives

- A variety of different teaching methods are used

- Different learning styles are respected

- High expectations for all students

- Formative evaluations are used systematically

- Teachers set clear objectives, monitor progress, and provide feedback

- Opportunities for classroom participation

- Diversity and individual differences are respected

- Social and emotional learning is valued

- Positive student-teacher and student-student relationships

- Classroom management strategies are systematic

- Disciplinary strategies are consistent and non-coercive

Teacher communities:

- Teachers participate in professional learning communities

- Teacher-teacher relationships are positive and collegial

- Teachers have time for common academic planning

- Teachers feel individually and collectively responsible for stu- dent learning

- Professional development is systematic and ongoing

- Teachers use data to support educational decision-making

Schools

- The principal provides instructional leadership:

- respects and fosters teacher professionalism

- shares decision-making with teachers

- articulates a clear and compelling vision that includes achievement, respect, and care

- models and supports ongoing professional learning and experimentation

- School policies and norms emphasize high achievement for all students

- Rules are clearly communicated and infractions are consistently addressed

- Students and staff feel physically safe

- Students and staff feel socially and emotionally safe

- Extra-curricular activities are available and all students are en- couraged to participate

- Facilities are clean and well-maintained

- Appropriate resources are available

As detailed throughout this paper, it is helpful to break these potential indicators down in relation to where they occur in order to get a holistic sense of a

school’s working practices. However, these indicators need to be considered as

a connected, interactive set. For example, establishing a compelling school vision across the school can occur through ongoing teacher community dialogue and collaboration that also enhances opportunities for students to participate in the classroom.

Data on school context can be collected through a variety of methods, including: focus groups, observational methods, interviews, town hall discussions, and surveys. Any approach should include students, teachers, staff, and parents, and should assess the full range of features that shape student and educator experiences of the school context (Cohen, Pickeral & McCloskey, 2008/2009).

The context concept characterizes schools as dynamic systems that influence

a broad range of dimensions of student learning, including academic, affective, social, and behavioral domains. A school’s context shapes the core processes of teaching and learning in classrooms. Teachers’ professional communities, extra-classroom learning opportunities, leadership decisions, teachers’ working conditions, and norms and values associated with the hidden curriculum all influence how teaching and learning are experienced in classrooms.

Studies of school context should draw from a variety of research methods in order to accurately capture the complexity of interactions among context factors. Understanding the contexts of particular schools enables educators, parents, students and policy makers to comprehend the possibilities for change and school improvement.

Bascia, N. (1994). Unions in teachers’ professional lives. New York: Teachers College Press.

Bascia, N. (1996). Caught in the crossfire: Restructuring, collaboration, and the “problem” school. Urban Education 31(2), 177-198.

Bascia, N., C. Connelly, J. Flessa & B. Mascall (2010). Ontario’s Primary Class Size Reduction Initiative: Report On Early Implementation. Report prepared for Ontario Ministry of Education. Toronto: Canadian Education Association.

Bascia, N., & B Faubert (2012). Physical space, spatiality and policy space: How class size reduction affects teaching and learning. Leadership and Policy in Schools.

Bascia, N., & C. Rottmann (2011). What’s so important about teachers’ working conditions?The fatal flaw in North American educational reform. Journal of Education Policy.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139 148.

Blackmore, J. & J. Kenway (1995). Changing schools, teachers, and curriculum: But what about the girls? In D. Corson (Ed)., Discourse and power in educational organizations.Toronto: OISE Press.

Bottery, M. (2004). The challenges of educational leadership. London: Paul Chapman. Boyd, V. (1992). School context: Bridge or barrier to change? Southwest Educational Development Laboratory. Retrieved from http://www.sedl.org/change/school/

Bryk, A., Sebring, P., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. (2010). Organizing schools for school improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Centre for Social and Emotional Education (2009). School climate guide for district policymakers and educational leaders. Available at http://www.schoolclimate.org/climate/documents/dg/district-guide-csee.pdf

Cohen, J. & J. Freiberg (2013). School climate and bullying prevention. National School Climate Center. Available at http://www.schoolclimate.org/publications/documents/sc-brief-bully-prevention.pdf

Cohen, D. & H. Hill (2001). Learning policy: When state education reform works. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cohen, J., McCabe, E., Michelli, N., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111(1), 180-213.

Cohen, D. K., M. McLaughlin & J. Talbert (1993). Teaching for understanding: Challenges for policy and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E. (2011). Predicting teacher commitment: The impact of school climate and social-emotional learning. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 1034-1048.

Connell, R. (1996). Teaching the boys: New research on masculinity, and gender strategies for schools. Teachers College Record 98(2), 206-235.

Day, C. & R. Leith (2007). The continuing professional development of teachers: Issues of coherence, cohesion and effectiveness. In T. Townsend (Ed.), International Handbook of School Effectiveness and Improvement, 468-83. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Deakin Crick, R., H. Green, S. Barr, A. Shafr & W. Peng (2013). Evaluating the wider outcomes of schooling: Complex systems modeling. Bristol, UK: Centre for Systems Learning & leadership, Graduate School of Education, University of Bristol.

EFA Global Monitoring Report (2005). Education for All: The Quality Imperative. Paris: UNESCO. Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001373/137333e.pdf

Galabawa, J. & Alphonse, N. (2005). Research on the quest for education quality indicators: Issues, discourse, and methodology: EdQual working paper No.2. Retrieved from http://www.edqual.org/publications/workingpaper/edqualwp2.pdf

Garet, M., A. Porter, L. Desimone, B. Birman & K. Yoon (2001). What makes professional development effective: Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal 38(4), 915-945.

Gu, Q. & Johansson, O. (2013). Sustaining school performance: School context matters. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 16(3), 301-326.

Hallinger, P. (2009). Leadership for 21st century schools: From instructional leadership to leadership for learning. Public Lecture Series. The Hong Kong Institute of Education.

September 23, 2009.

Kim, K. T. (2012). Using process indicators to facilitate data-driven decision making in an era of accountability. Creative Education, 3(6), 685-691.

Leithwood, K. 2006. Teacher working conditions that matter: Evidence for change. Toronto: Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario. Available at http://www.etfo. ca/Resources/ForTeachers/Documents/Teacher Working Conditions That Matter – Evidence for Change.pdf

Little, J. W. 1992. Opening the black box of teachers’ professional communities. In A. Lieberman (Ed.), Building a professional culture in schools, The changing contexts of teaching, 158–78. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Louis, K.S. 1992. Restructuring the problem of teachers’ work. In A. Lieberman (Ed.), Building a professional culture in schools, 138–56. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

MacBeath, J., & McGlynn, A. (2002). Self-evaluation: What’s in it for Schools? Routledge.

McLaughlin, M. (1993). What matters most in teachers’ workplace context? In J. Little & M. McLaughlin (Eds.), Teachers’ work: Individuals, colleagues and contexts, 79-103. New York: Teachers College Press.

McLaughlin, M. and S. Yee. 1988. School as a place to have a career. In Building a professional culture in schools, ed. A. Lieberman, 23–44. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

Mintrop, H. & Trujillo, T. (2007). Practical relevance of accountability systems for school improvement: A descriptive analysis of California schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 29(4), 319-352.

National College for School Leadership (2004). Learning-centred Leadership: Towards personalised learning-centred leadership. Available at http://www.nationalcollege.org.uk/lcl-towards-personalised-lcl.pdf

National School Climate Council (2007). National school climate standards. Available at http://www.schoolclimate.org/climate/documents/school-climate-standards-csee.pdf Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping Track: How schools structure inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Oakes, J. (1989). What educational indicators? The case for assessing the school context. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(2), 181-199.

Phelan, P., A. Davidson & H. Yu (1996). Adolescents’ worlds: Negotiating family, peers and school. New York: Teachers College Press.

Pickeral, T., Evans, L., Hughes, W. & Hutchison, D. (2009). School Climate Guide for District Policymakers and Educational Leaders. New York, NY: Center for Social and Emotional Education.

Porter, A. (1991). Creating a system of school process indicators. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 13(1), 13-29.

Sackney, L. (2007). History of the school effectiveness and improvement movement in Canada over the past 25 years. In T. Townsend (Ed.), International Handbook of School Effectiveness and Improvement, 167-182. Springer.

Scheerens, J. (2011). Measuring educational quality by means of indicators. In J. Scheerens, H. Luyten, & J. van Ravens (Eds.), Perspectives on educational quality: Illustrative outcomes on primary and secondary schooling in the Netherlands (pp. 35-52). Dordrecht: Springer.

Siskin, L. (1994). Realms of knowledge: Academic departments in secondary schools. London: The Falmer Press.

Talbert, J. & M. McLaughlin (1999). Assessing the school environment: Embedded contexts and bottom-up research strategies. In S. Friedman & T. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span, 197-227. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Voight, A., Austin, G., Hanson, (2013). A climate for academic success: How school climate distinguishes schools that are beating the achievement odds (Full Report). San Francisco: WestEd.

Watkins, C. (2005). Classrooms as Learning Communities: What’s in it for schools. London: Routledge Falmer.

Werner, W. (1991). Curriculum and uncertainty. In R. Ghosh & D. Ray (Eds.), Social change and education in Canada (2nd edition), 105-115. Toronto: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Yee, S. 1990. Careers in the classroom: When teaching is more than a job. New York: Teachers College Press.

People for Education – working with experts from across Canada – is leading a multi-year project to broaden the Canadian de nition of school success by expanding the indicators we use to measure schools’ progress in a number of vital areas.

The domain papers were produced under the expert guidance of Charles Ungerleider and Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group.

Author

Dr. Nina Bascia

University of Toronto

The Measuring What Matters reports and papers were developed in partnership with lead authors of each domain paper. Permission to photocopy or otherwise reproduce copyrighted material published in this paper should be submitted to Dr. Nina Bascia at [email protected] or People for Education at [email protected].

Document Citation

This report should be cited in the following manner:

Bascia, N. (2014). The School Context Model: How School Environments Shape Students’ Opportunities to Learn. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014

We are immensely grateful for the support of all our partners and supporters, who make this work possible.

Annie Kidder, Executive Director, People for Education

David Cameron, Research Director, People for Education

Charles Ungerleider, Professor Emeritus, Educational Studies, The University of British Columbia and Director of Research, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Lindy Amato, Director, Professional A airs, Ontario Teachers’ Federation

Nina Bascia, Professor and Director, Collaborative Educational Policy Program, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Ruth Baumann, Partner, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Kathy Bickmore, Professor, Curriculum, Teaching and Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Michelle Boucher, University of Ottawa, Advisors in French-language education and Ron Canuel, President & CEO, Canadian Education Association

Ruth Childs, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Jean Clinton, Associate Clinical Professor, McMaster University, Dept of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences

Gerry Connelly, Director, Policy and Knowledge Mobilization, The Learning Partnership

J.C. Couture, Associate Coordinator, Research, Alberta Teachers’ Association

Fiona Deller, Executive Director, Policy and Partnerships, Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario

Kadriye Ercikan, Professor, Measurement, Evaluation and Research Methodology, University of British Columbia

Bruce Ferguson, Professor of Psychiatry, Psychology, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto; Community Health Systems Research Group, SickKids

Joseph Flessa, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Joan M. Green, O.Ont., Founding Chief Executive O cer of EQAO, International Education Consultant

Andy Hargreaves, Thomas More Brennan Chair, Lynch School of Education, Boston College Eunice

Eunhee Jang, Associate Professor, Department of Applied Psychology & Human Development, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Christopher Kotz, Senior Policy Advisor, Ontario Ministry of Education

Ann Lieberman, Stanford Centre for Opportunity Policy in Education, Professor Emeritus, Teachers College, Columbia University

John Malloy, Director of Education, Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board

Roger Martin, Premier’s Chair on Competitiveness and Productivity, Director of the Martin Prosperity Institute, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Ayasha Mayr Handel, Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services

Catherine McCullough, former Director of Education, Sudbury Catholic District School Board

Robert Ock, Healthy Active Living Unit, Health Promotion Implementation Branch, Health Promotion Division, Ontario Ministry of Health

Charles Pascal, Professor, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Jennifer Riel, Associate Director, Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Joanne Robinson, Director of Professional Learning, Education Leadership Canada, Ontario Principals’ Council

Bruce Rodrigues, Chief Executive Officer, Ontario Education Quality and Accountability Office

Pasi Sahlberg, Director General, Centre for International Mobility and Cooperation, Finland

Alan Sears, Professor of social studies and citizenship education, University of New Brunswick

Stuart Shanker, Research Professor, Philosophy and Psychology, York University; Director, Milton and Ethel Harris Research Initiative, York University; Canadian Self-Regulation Initiative

Michel St. Germain, University of Ottawa, Advisors in French-language education

Kate Tilleczek, Professor and Canada Research Chair, Director, Young Lives Research, University of Prince Edward Island

Rena Upitis, Professor of Education, Queen’s University

Sue Winton, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Education, York University and former Early Learning Advisor to the Premier Deputy Minister of Education