The report based on findings from the Annual Ontario School Survey reveals many gaps in the province’s first steps toward de-streaming Grade 9, including staffing, hybrid learning, mental health and well-being of staff and students; and also makes recommendations for changes to support the full implementation of de-streaming in the fall of 2022.

Timing is everything: The implementation of de-streaming in Ontario's publicly funded schools

The 2021–22 school year tested some of society’s fundamental assumptions about public education: the role of educators, technology, funding, evaluation, human connection and, of course, education pathways in student learning.

This report uses People for Education’s Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS) 2021–22 data to examine the implementation of de-streaming Grade 9 mathematics in Ontario’s publicly funded schools.

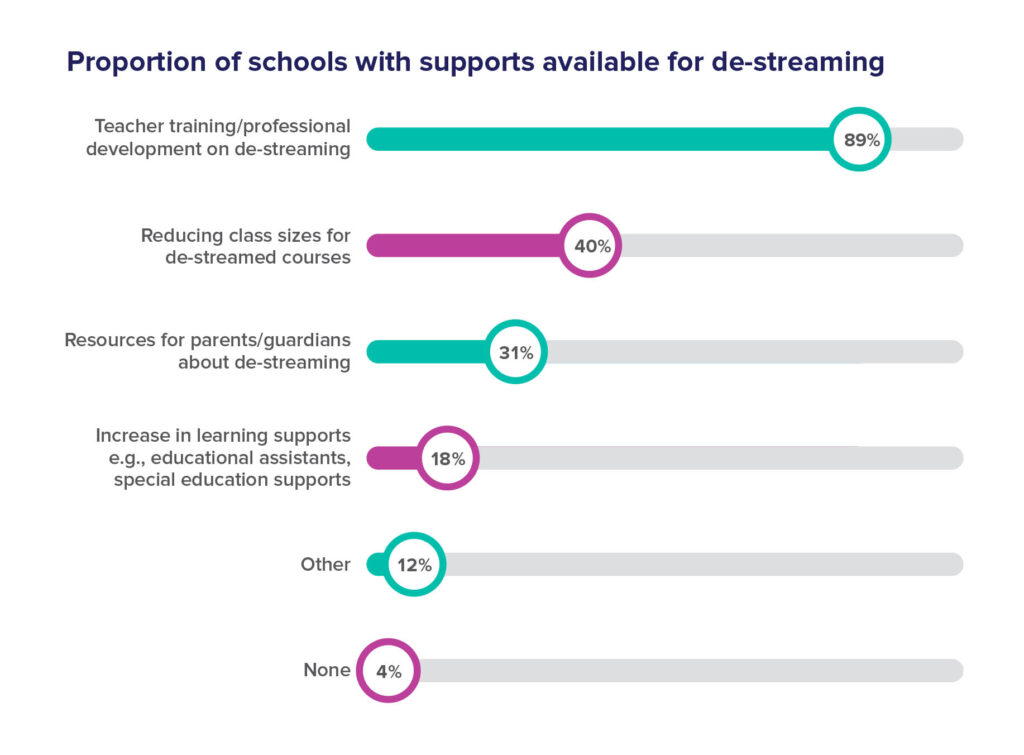

While the government provided some funding to support de-streaming, only 30% of principals said that the support was sufficient. The vast majority of principals (89%) reported that professional development and teacher training on de-streaming was available, but far fewer reported having access to things like smaller class sizes and parent/guardian resources to support the implementation of de-streaming. The most prominent finding, however, was how these data varied by geography and income level.

While the decision to de-stream is a step in the right direction toward eliminating the negative impacts that this structural approach has had on Black, Indigenous, racialized, special needs, and low-income students, the AOSS 2021–22 data reveal that its implementation has not been consistently executed across the province. These inconsistencies are critical to consider as the implementation of de-streaming moves forward in September 2022 with a new de-streamed Grade 9 science curriculum as well as the de-streaming of all Grade 9 courses.

Recent findings have shown that principals across Ontario are experiencing a “perfect storm of stress” where staffing shortages and a lack of well-being supports are making it one of the most difficult school years they have experienced (People for Education 2022). The decision to implement de-streaming during a global pandemic requires a clear and comprehensive plan.

People for Education has three key recommendations to ensure the implementation of de-streaming across Ontario’s publicly funded schools is equitable, sustainable, and above all, successful for all students.

- Plan in consultation with students, educators, education support staff, and families.

- Provide learning supports for de-streaming that meet schools’ different needs.

- Monitor and evaluate implementation as frequently as possible.

In fall 2021, People for Education conducted the Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS) 2021–22 and asked principals in Ontario’s publicly funded secondary schools about the recent implementation of de-streaming. These findings are among the first publicly reported data on the implementation of the new de-streamed Grade 9 mathematics curriculum in September 2021. These data provide insights on the types of supports that were provided to schools (e.g., professional development, teacher training, additional staff, family resources, etc.) to facilitate the de-streaming process as well as the regional and socioeconomic differences in these learning supports’ availability. Findings also include principals’ perspectives on the roll-out of de-streaming in their schools and the support that the Ministry of Education provided. Building on these newly available data, People for Education proposes three key policy recommendations to ensure the success and sustainability of de-streaming.

In education, the practice of streaming refers to the process of separating students into distinct schooling pathways based on their perceived ability and/or prior achievement. Numerous studies have demonstrated that academic streaming has advantaged some populations while systematically marginalizing others (Brown 1996; Brown and Parekh 2013; Brown and Tam 2017; James and Turner 2017; Oakes 2005; People for Education 2013, 2015). Most notably, Black students, Indigenous students, students with special education needs, and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are disproportionately placed in these lower streams (i.e., applied and essentials), which are often associated with poorer educational outcomes. Compared to those from higher academic streams, students from lower streams are also suspended at a higher rate and are less likely to graduate from high school and enter college or university as postsecondary destinations. The Ministry of Education identified these trends as an “unintended consequence” of academic streaming (Ontario Ministry of Education 2017, 14).

In 2020—in the middle of a global pandemic—the Ontario government announced that de-streaming for Grade 9 students would begin with a new de-streamed math curriculum to be implemented in September 2021 (Office of the Premier 2020). To prepare for the most recent implementation of de-streaming, The Ontario Curriculum, Grade 9: Mathematics, 2021 was released in June 2021, providing teachers and schools with three months to prepare for its delivery (Ontario Ministry of Education 2021a).

Typically, a curriculum roll-out that factors in preparation, planning, monitoring, and adaptation involves a multi-year plan for the implementation to be effective (Goldsmith, Mark, and Kantrov 2008). Nevertheless, in November 2021, it was announced that beginning in September 2022, all Grade 9 subjects will be offered in one stream (Ontario Ministry of Education 2021c). While there will be a new curriculum for Grade 9 Science released in spring 2022, the de-streaming plan for the remaining compulsory Grade 9 subjects (i.e., English, French, and Geography) will use the existing academic course curricula.

In the AOSS 2021–22, principals of secondary and elementary/secondary combination schools were asked to indicate what supports were available to assist with the implementation of de-streaming Grade 9 mathematics in the 2021–22 school year (Figure 1). Most respondents (89%) reported that teacher training and/or professional development on de-streaming was available. Less than half of principals reported that smaller class sizes (40%), resources for parents/guardians (31%), and an increase in learning supports (18%) were offered. Of the 12% of responses that indicated the availability of “other” resources, principals elaborated on offerings such as before-/after-school and lunchtime support programs for students who need extra help in de-streamed courses. Four percent of principals responded that their school did not offer any supports for the implementation of de-streaming.

Figure 1. Available de-streaming supports reported by secondary and elementary/secondary school principals, AOSS 2021–22

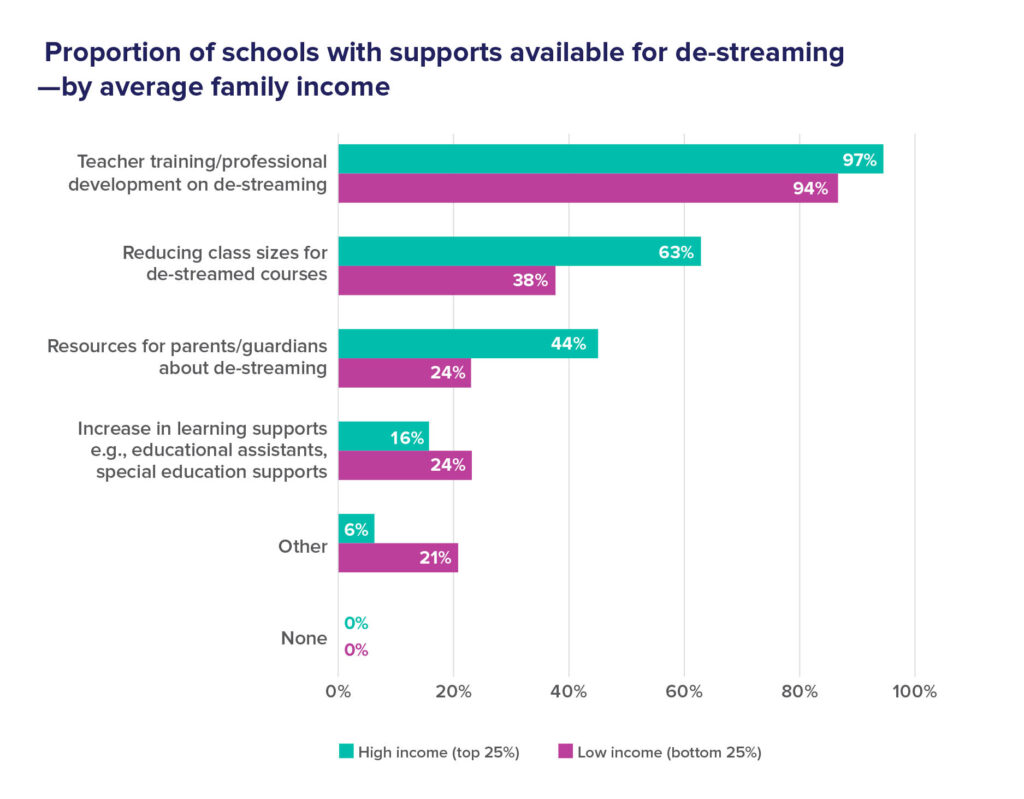

While only a minority of principals reported an increase in learning supports, there were meaningful differences along socioeconomic lines.

There is evidence that successful de-streaming models include increased learning supports for students, along with dedicated educational assistants, lunch-hour or after-school tutoring, and supplementary learning resources to ensure students are supported during the implementation of de-streaming (Pichette, Deller, and Colyar 2020). In reviewing the data by average family income of school neighbourhood, findings showed that 24% of principals from schools located in low-income areas reported that their schools offered increased learning supports to assist with de-streaming, compared to 16% of principals from schools located in high-income neighbourhoods (Figure 2). However, principals in schools from higher-income neighbourhoods were more likely to report that their schools had supports such as teacher training, reduced class size, and resources for parent/guardians.

Figure 2. Available de-streaming supports reported by secondary and elementary/secondary school principals, by 2016 median census family income of school neighbourhood, AOSS 2021–22

In February 2022, the Ontario Ministry of Education announced its Grants for Student Needs (GSNs), which, along with funding for temporary staffing to support pandemic recovery, included funding required for the implementation of de-streaming in a few different areas: temporary additional staffing, early intervention in math for students with special needs, board-based math learning leads, and transition supports for Grade 8 students entering Grade 9 (Ontario Ministry of Education 2022). The funding has specific time constraints and its distribution is piecemeal across various areas of need. While some of the issues that are addressed, such as learning recovery and remote learning, may be relevant in the short-term only, the plan for de-streamed Grade 9 courses does not have an end date. There is currently no commitment to long-term funding to support the future or sustainability of de-streaming in Ontario’s publicly funded schools beyond its implementation stage.

Most schools were able to offer training to staff, with 89% of principals reporting that teacher training and professional development was an available de-streaming support at their school. However, principals described facing multiple challenges with getting teachers effectively trained within such a short time span, amid the additional challenge of dealing with the constraints brought on by the pandemic.

“There have been far too many interruptions since the declaration of de-streaming: job action, pandemic. Many learnings have been cancelled, modified to accommodate to Zoom, etc. There is also a lack of universal expertise in getting effective professional learning in the context of real classroom learning. Theory is one thing: practice quite another.”

―Secondary school principal, GTA

Multiple reports on de-streaming in Ontario have highlighted the need for teacher training and professional development as a requirement, if not a prerequisite, for the successful and sustained implementation of de-streaming in Ontario schools (Follwell and Andrey 2021; Ontario Teachers’ Federation 2021; Pichette, Deller, and Colyar 2020).

“Robust and sustained training for teachers and educational workers will be necessary for them to implement and deliver an effective de-streamed mathematics program. Thus, it is imperative that the Ministry and school boards provide all teachers and educational workers both with appropriate training during the instructional day and access to fully developed resources well before they are expected to implement a new mathematics curriculum in de-streamed classrooms.” (Ontario Teachers’ Federation 2021, 3)

Despite the call for professional development to support teachers in this transition, the June 2021 release of the new de-streamed curriculum for grade 9 mathematics, gave Ontario schools only two months to prepare for its delivery. As a result of the limited time frame for implementation, professional development and teacher training have taken place concurrently with the roll-out of the new Grade 9 mathematics curriculum.

The numerous interruptions to the school calendar, the back-and-forth changes in pedagogical approaches between in-person, online learning, and hybrid―in addition to the staffing shortages brought on by the pandemic―meant that delivering consistent and effective professional development on de-streaming has been a challenge for schools. Principals noted the critical need for more substantial and consistent training and professional development for teachers prior to fully de-streaming Grade 9 in September 2022.

“Training for math teachers on de-streaming came quite late in the year last year and, while it has been ongoing this year, it is still a challenge. Significant training (in the very near future) will be required for teachers in the other de-streamed subject areas as well.”

―Secondary school principal, Northern Ontario

Educator “buy-in” is essential to effective professional development, and it takes time

Sustaining systemic changes in education, such as de-streaming, require educator “buy-in” (Pichette, Deller, and Colyar 2020). Professional development is critical for teachers―not just in preparing for changes in curriculum and instructional strategies but also to provide a space to engage in discussions that lead to broader cultural shifts in beliefs, attitudes, and values. For example, professional development initiatives that critically explore the topic of streaming through an anti-oppressive and anti-racist lens enable educators to recognize the importance of de-streaming and shift their mindsets and teaching practices (Pichette, Deller, and Colyar 2020; San Vincente 2015).

In an August 2021 Ministry of Education memorandum on professional development for teachers, there were three mandatory professional activity days allocated for all school boards to cover about a dozen different topics, ranging from health and safety protocols to cyberbullying (Ontario Ministry of Education 2021b). Training on de-streaming for Grade 9 mathematics is included as one component of a broader mathematics training, while anti-racism and anti-discrimination training is one of several other topics to be covered.

This approach is not backed up by evidence about effective professional development on de-streaming, which outlines the importance of providing time and space for teachers to critically engage with issues related to streaming, examine implicit biases, question their underlying assumptions, and build a supportive community of practice. The Ontario Ministry of Education has noted that an updated memorandum on professional activity will be published shortly for the 2022–2023 school year.

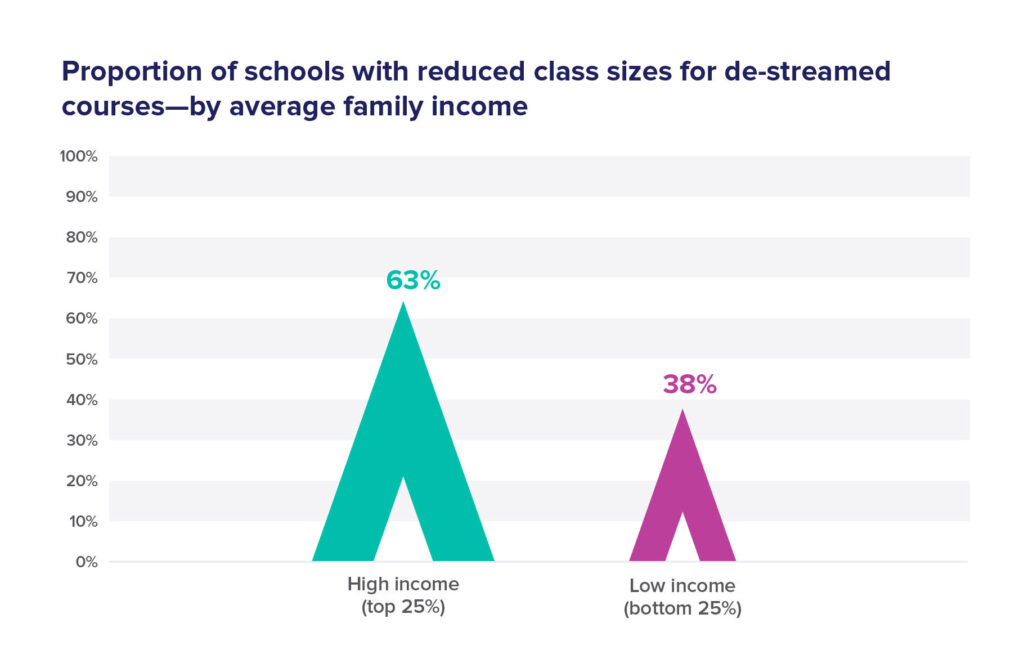

There is substantial evidence to suggest that the benefits of reduced class size are greatest for students who are socially and economically disadvantaged (Bascia and Fredua-Kwarteng 2008; Follwell and Andrey 2021; People for Education 2007). However, principals in high-income neighbourhoods were much more likely (63%) than schools in low-income neighbourhoods (38%) to report that reduced class sizes for de-streamed courses were available at their schools (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Proportion of secondary and elementary/secondary principals who reported reduced class sizes for de-streamed courses as an available de-streaming support in their school, by 2016 median census family income of school neighbourhood, AOSS 2021–22

Targeting class size reduction

This finding suggests that while class size reduction is currently a support offered by some schools, it is less likely to be offered in schools in low-income neighbourhoods, where the negative impacts of streaming are most felt, and where students are more likely to experience greater benefits from reduced class size. However, class size reduction alone may not lead to greater student outcomes if teaching strategies remain unchanged―it must also be accompanied by changes in pedagogy that make use of the opportunities for learning offered by smaller class sizes (Bascia and Fredua-Kwarteng 2008; Graue and Rauscher 2009).

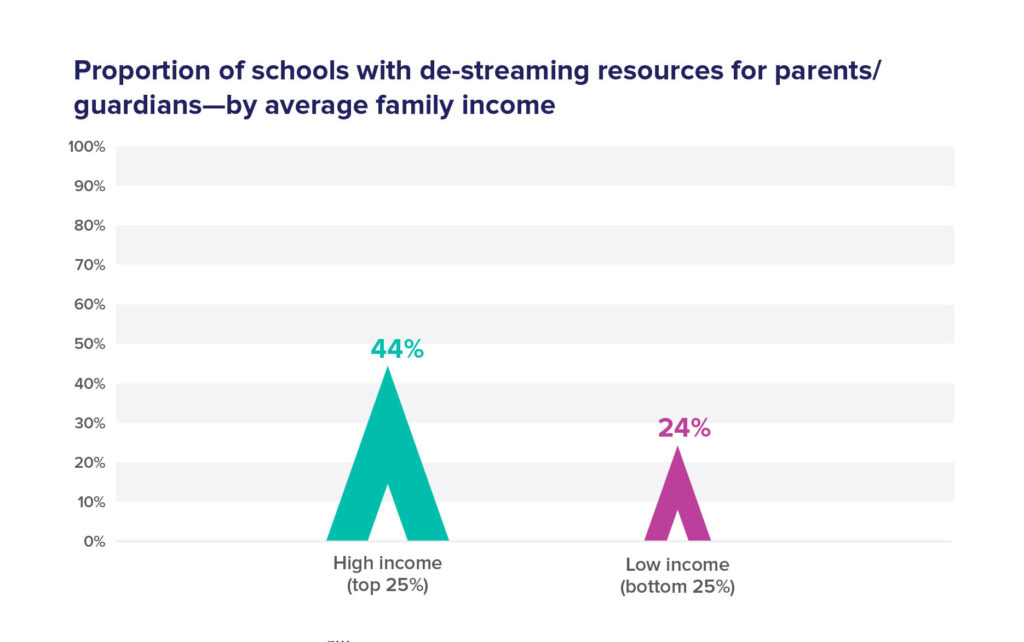

The Ministry of Education has acknowledged that community engagement with marginalized communities, students, and parents is an important part of removing systemic barriers in Ontario’s publicly funded schools (Ontario Ministry of Education 2017). However, when principals were asked what de-streaming supports were available in their schools, only 31% reported having resources available for parents and guardians about de-streaming.

Because students in low-income communities are more likely to be placed in applied streams, improving the availability of parent/guardian resources about the process of de-streaming is critical to supporting these students. Despite this, a comparison of high-income and low-income school neighbourhoods showed that the availability of parent and guardian resources on de-streaming reported by principals in low-income communities (24%) was about half that reported in high-income communities (44%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Proportion of secondary and elementary/secondary principals who reported resources for parents/guardians about de-streaming in their school, by 2016 median census family income of school neighbourhood, AOSS 2021–22

Parent/guardian and family support is critical for student success but the responsibility to engage families is often neglected in marginalized communities (Henderson and Mapp 2002; James and Turner 2017). Fostering community engagement and increasing the availability of resources for parents and guardians on de-streaming in all of Ontario’s publicly funded schools is necessary, but prioritizing outreach and support within low-income, racialized, and other marginalized communities is key to supporting the students that streaming has most negatively affected in the past.

While the policy announcement from the Ontario Ministry of Education in 2020 to de-stream Grade 9 mathematics was a critical first step toward addressing the systemic inequities caused by streaming, there are several more components that need to be developed for this implementation to be successful.

“Timelines for implementing the math curriculum were near impossible for doing a good job at implementing the de-streamed math for this year. It was the worst roll-out of a curriculum change I have been involved with since I began in education in 1997.”

― Elementary and secondary school principal, Eastern Ontario

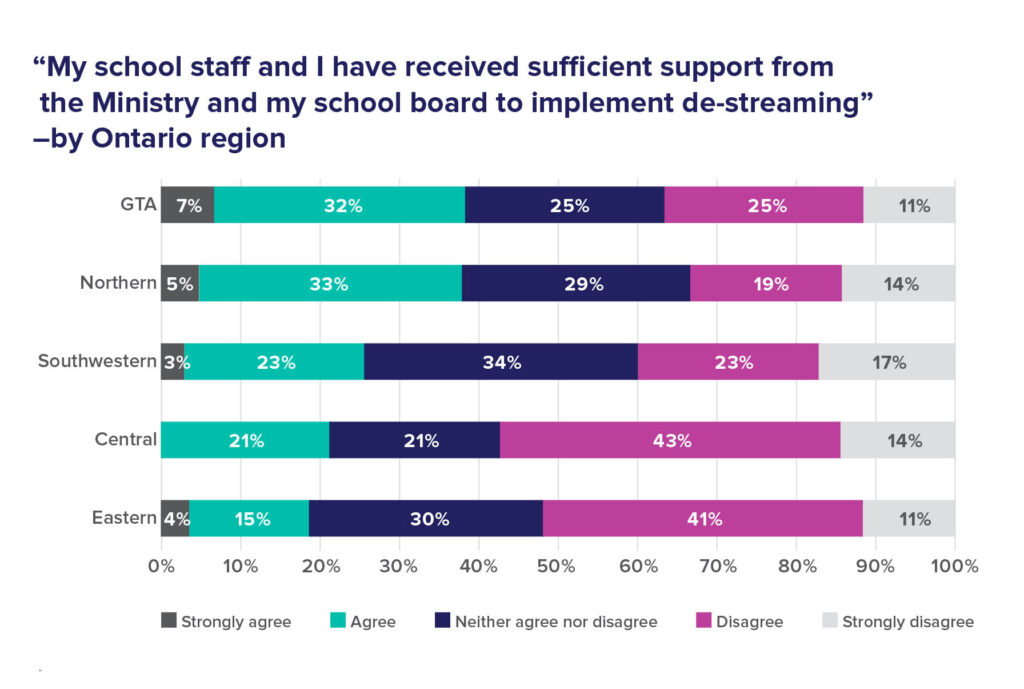

Secondary and elementary/secondary school principals were asked how much they agreed with the statement, “My school staff and I have received sufficient support from the Ministry and my school board to implement de-streaming.” Only 30% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while 42% of principals disagreed or strongly disagreed. When the findings were disaggregated by geographical region, there were some significant differences between regions (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Secondary and elementary/secondary school principals’ perceptions of the degree of governmental and board support they had with implementing de-streaming, by Ontario region, AOSS 2021–22

While many principals in the GTA (39%) and Northern Ontario (38%) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement on ministry and board support, more than half of the principals in Central (57%) and Eastern Ontario (52%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. Some principals described problems with the lack of ministry support with implementing de-streaming:

“Our board, like most boards has had to scramble to support teachers because of the lack of direction from the Ministry.”

―Secondary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

“My school board has provided good collaboration sessions for my math teachers. I have worked with my staff on supports to help our students succeed in our de-streamed English classes. Having our LRT [Learning Resource Teacher] work alongside our Math and English teachers has helped students to be successful in our de-streamed classes. I don’t really recall any great supports from the Ministry to support this change.”

―Secondary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

“Few resources for curriculum delivery; plan rolled out with too much of a focus on rationale and too little on curriculum resources to support teachers and students in the classroom.”

― Secondary school principal, GTA

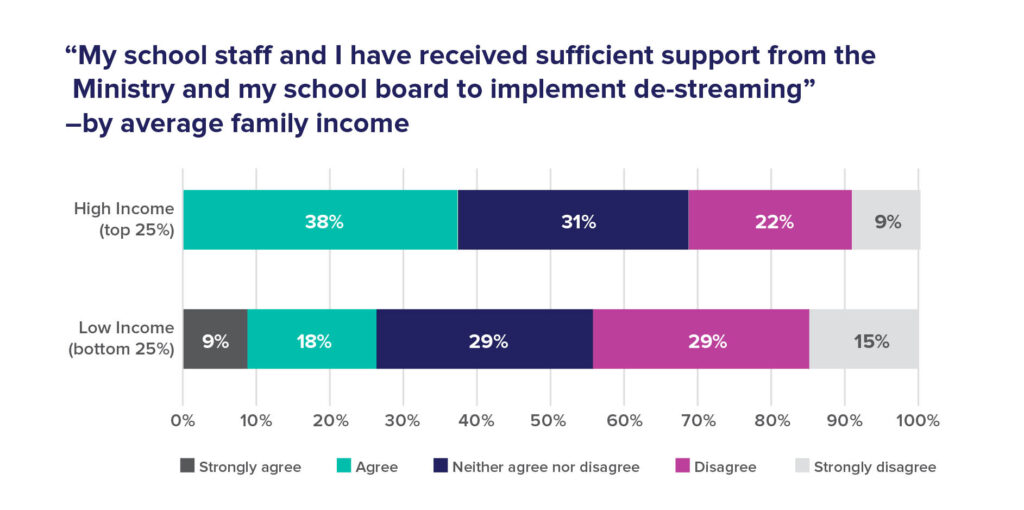

Moreover, a higher proportion of principals in high-income school neighbourhoods (38%) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement than principals in low-income school neighbourhoods (27%) (Figure 6). Considering that students from lower-income households have been disproportionately placed in lower streams (i.e., applied or essentials), principals and staff of schools located in low-income communities may require additional board and ministry assistance or support that is more tailored to their needs to ensure that their students are sufficiently supported during the de-streaming transition.

Figure 6. Secondary and elementary/secondary school principals’ perceptions of the degree of governmental and board support they had with implementing de-streaming, by 2016 median census family income of school neighbourhood, AOSS 2021–22

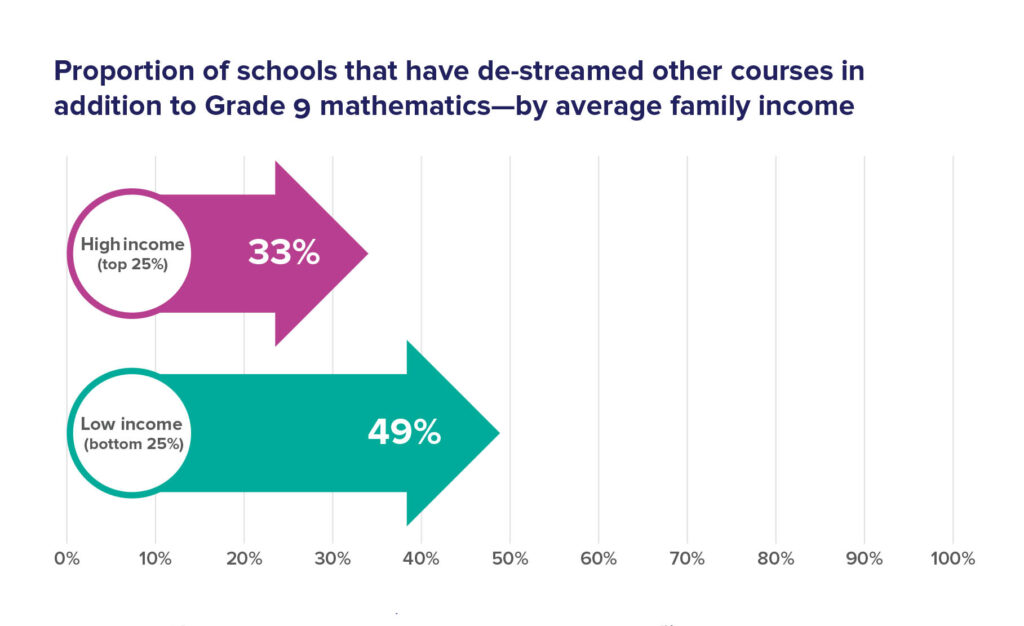

Thirty-five percent of principals reported that their schools had de-streamed other courses in addition to Grade 9 mathematics. English was the most frequently reported course that these principals had opted to de-stream, followed by geography, science, and French. Looking at the responses regionally, the proportion of principals who reported that their schools had de-streamed any other courses besides grade 9 math was 19% in Eastern Ontario, 20% in Central Ontario, 29% in Northern Ontario, 34% in Southwestern Ontario, and 53% in the GTA.

A handful of secondary-school principals, all located in the GTA, reported that they had de-streamed all Grade 9 courses. A small number (<10) responded that they had de-streamed all courses at both the Grade 9 as well as Grade 10 levels.

Analyzing the data by the median family income of the school neighborhood, 33% of principals of schools in high-income neighbourhoods reported that they had de-streamed other courses in addition to Grade 9 mathematics, compared to 49% of principals from schools located in low-income neighbourhoods (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Proportion of secondary and elementary/secondary principals reporting their school has de-streamed other courses in addition to Grade 9 mathematics, by 2016 median census family income of school neighbourhood, AOSS 2021–22

The findings from the AOSS 2021–22 are among the first publicly available data on the implementation of de-streaming Grade 9 mathematics in Ontario’s publicly funded schools. While the decision to de-stream is a step in the right direction toward eliminating the negative impacts that this structural approach has had on Black, Indigenous, racialized, special needs, and low-income students, the findings show that its implementation has not been consistently executed across the province. Not only do the discrepancies in learning supports made available for the implementation of de-streaming vary from region to region, but there are also significant differences between schools in low- and high-income family neighbourhoods.

These inconsistencies are critical to consider as the implementation of de-streaming moves forward in September 2022 with a new de-streamed Grade 9 science curriculum as well as the de-streaming of all Grade 9 courses. If the Ontario government is making these changes to ensure that all students can reach their full potential, then the learning supports required for a successful implementation need to be planned in consultation with schools, educators, students, and families to best respond to local needs and contexts.

People for Education supports the following three policy recommendations for the successful implementation of de-streaming in Ontario’s publicly funded schools:

1) Plan in consultation with students, educators, education support staff, and families.

De-streaming has and will continue to have direct implications not just for educators and students, but also for families and the broader school community. The inequities of the pandemic have further exacerbated barriers that Indigenous, Black, racialized, special needs, and low-income students and their families face. Educators, similarly, have faced barriers and described feeling unvalued and unconsidered when it comes to decision making (People for Education 2022). An equitable implementation strategy must be developed in consultation with students, educators, education support staff, and families. Students and families need to be key partners in the implementation process, in addition to educators who need to feel meaningfully involved alongside administration and the Ministry (CASE 2022). To make this a reality, the ministry and Ontario school boards must create conditions where all stakeholders, especially Black, Indigenous, and racialized students, as well as other marginalized individuals, feel heard, included, and valued.

2) Provide increased learning supports for de-streaming that meet schools’ different needs.

De-streaming is a significant structural, pedagogical, and cultural change for schools and school boards, and it will continue to require significant support and investment. However, current professional development opportunities and training are not equitably distributed, nor sufficient to support the current de-streamed math curriculum. These discrepancies pose concerns for expansion to include all Grade 9 curricula because the need for support will increase exponentially and current inequities will only be exacerbated.

Increased supports for de-streaming are needed across Ontario in the form of reduced class sizes, accessible resource programs, and implementation plans created in collaboration with students, families, educators, and education staff. Without additional funding, Ontario’s de-streaming process will be heavily under resourced, with administrators and educators feeling further forgotten, stressed, and un(der)supported. To set students and educators up for success, the provincial government must learn from past de-streaming efforts that documented the additional learning supports needed and invest in similar targeted supports for students and educators alike.

3) Monitor and evaluate implementation as frequently as possible.

Evaluation is needed to inform evidenced-based policy and practice for de-streamed curriculum. De-streaming curricula is not enough to ensure successful outcomes for equity-deserving students. An understanding of academic attainment and student well-being is necessary to determine the success of de-streaming in improving outcomes for Black, Indigenous, racialized, special needs, low-income students, and those most marginalized in education. Gaining this breadth and depth of understanding will require an intersectional approach to evaluation and data analysis.

To this end, People for Education recommends that the Ministry of Education and school boards prioritize evaluation to keep track of whether de-streaming in Ontario education is achieving the desired outcomes and where additional support may be most needed. This recommendation is well-aligned with the Board Improvement and Equity Plan (BIEP), which is a standardized tool grounded in the collection of disaggregated demographic data to support school boards in tracking student achievement, equity, well-being, and transitions (Ontario Ministry of Education 2021d, 2021e). A collective commitment is needed to leverage both school board data and third-party research data to determine best practices, challenges, impact, and innovative approaches to implementation. Further, as the Coalition for Alternatives to Streaming in Education recommends (CASE 2022), appropriate evaluation is needed to ensure that schools do not see an increase in registrations for locally developed courses, which would undermine the goals of de-streaming to improve outcomes for equity-deserving students.

As the ministry continues to expand its plan to de-stream public education in Ontario, it is important to recognize that streaming alone is not responsible for the inequities that disadvantage Black, Indigenous, racialized, special needs, and low-income students experience in education. Streaming is part of a larger network of inequities and exclusion in education and de-streaming is one way to address the systemic racism, classism, and oppression present in Ontario schools. However, de-streaming needs to be part of a broader discourse on equity in education and recognized as just the first step in an ongoing journey toward equitable education reform.

Every year, People for Education (PFE) surveys Ontario’s publicly funded schools. This report is based on data from the schools that participated in the Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS) 2021–22. Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and material quoted here originate from the 184 survey responses we received from principals of secondary schools and schools that house both elementary and secondary students (there were 142 secondary school responses and 42 elementary/secondary school responses). All direct quotations appear exactly as written (including capitalization and emphasis) by survey respondents, unless otherwise stated. Surveys were completed online via SurveyMonkey in both English and French between October 19, 2021, and January 17, 2022.

Survey responses were disaggregated to examine representation across provincial regions (see Figure 8). Schools were sorted into geographical regions based on the first letter of their postal code. The GTA region includes schools with M postal codes as well as those with L postal codes located in GTA municipalities (City of Toronto n.d.).

Figure 8. Survey response representation by region, secondary schools, AOSS 2021–22

During analysis, data collected from the survey were matched with the Weighted Average Median Census Family Income by School, 2017–2018, which was provided to PFE through a Request for Information request from the Ontario Ministry of Education’s Education Statistics and Analysis Branch. The Median Census Family Income information was derived from the 2016 census for all the dissemination areas associated with a school based on its students’ weighted enrolment by residential postal code. Schools were then sorted from highest to lowest income based on this measure. In this report, the top 25% of secondary schools and elementary/secondary combination schools based on Weighted Census Family Income are considered “high income” (n = 44; average income = $112,492) and the bottom 25% are considered “low income” (n = 44; average income = $64,596), unless otherwise specified.

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using inductive analysis. Researchers read responses and coded emergent themes in each set of data (i.e., the responses to each of the survey’s open-ended questions). The quantitative analyses in this report are based on descriptive statistics. The primary objective of the descriptive analyses is to present numerical information in a format that is accessible to a broad public readership. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. All calculations have been rounded to the nearest whole number and may not total 100% in displays of disaggregated categories.

For other questions about the methodology used in this report, please contact the research team at PFE: [email protected].

Bascia, Nina, and Eric Fredua-Kwarteng. 2008. “Class Size Reduction: What the Literature Suggests about What Works.” Toronto: Canadian Education Association. https://www.edcan.ca/wp-content/uploads/cea-2008-class-size-literature.pdf.

Brown, Robert. 1996. “Tracking of Grade 9 and 10 Students in the Toronto Board: September 1991–September 1995.” Toronto Board of Education. Accessed on March 25, 2022. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED404757.pdf.

Brown, Robert, and Gillian Parekh. 2013. “The Intersection of Disability, Achievement, and Equity: A System Review of Special Education in the TDSB (Research Report No. 12-13-12).” Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Toronto District School Board. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/research/docs/reports/Intersection%20of%20Disability%20Achievement%20and%20Equity.pdf.

Brown, Robert, and George Tam. 2017. “Grade 9 Cohort Post-Secondary Pathways, 2011–16.” Fact Sheet 3, November 2017. Toronto District School Board. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/research/docs/reports/FS3%20Grade%209%20Cohort%20Post-Sec%20Pathways%202011-16%20FINAL.pdf.

City of Toronto. n.d. “City Halls―GTA Municipalities and Municipalities Outside of the GTA.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.toronto.ca/home/311-toronto-at-your-service/find-service-information/article/?kb=kA06g000001cvbdCAA.

Coalition for Alternatives to Streaming in Education (CASE). 2022. “CASE Fact Sheet and Recommendations.” April. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ee2aedfd4916c68b6bb2c26/t/623c92d49c1ecd2e26c4c42a/1648136916999/CASE_FactSheet_V11.pdf.

Follwell, Tianna, and Sam Andrey. 2021. “How to End Streaming in Ontario Schools.” Ontario 360. May 13, 2021. https://on360.ca/policy-papers/how-to-end-streaming-in-ontario-schools/.

Goldsmith, Lynn, June Mark, and Ilene Kantrov. 2008. “Choosing a Standards-Based Mathematics Curriculum.” Education Development Center. Accessed April 1, 2022. http://mcc.edc.org/mguide.php.

Government of Ontario. 2022. “Locally Developed Courses.” March 11. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://data.ontario.ca/dataset/locally-developed-courses#:~:text=Locally%20developed%20courses%20are%20courses,the%20provincial%20curriculum%20policy%20documents.

Graue, Elizabeth, and Erica Rauscher. 2009. “Researcher Perspectives on Class Size Reduction.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 17 (May): 9. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v17n9.2009.

Henderson, Anne T., and Karen L. Mapp. 2002 “A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement. Annual Synthesis, 2002.” Southwest Educational Development Lab, Austin, TX. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED474521.pdf.

James, Carl E., and Tana Turner. 2017. “Towards Race Equity in Education: The Schooling of Black Students in the Greater Toronto Area.” Toronto, York University, April. https://edu.yorku.ca/files/2017/04/Towards-Race-Equity-in-Education-April-2017.pdf.

Oakes, Jeannie. 2005. Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Office of the Premier. 2020. “Ontario Taking Bold Action to Address Racism and Inequity in Schools.” July 9, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/57543/ontario-taking-bold-action-to-address-racism-and-inequity-in-schools.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2017. “Ontario’s Education Equity Action Plan.” Accessed March 22, 2022. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/about/education_equity_plan_en.pdf.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021a. “Modernizing Grade 9 Math Education in Ontario Schools.” June 9, 2021. https://news.ontario.ca/en/backgrounder/1000299/modernizing-grade-9-math-education-in-ontario-schools.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021b. “Professional Activity Days Devoted to Provincial Education Priorities” (Policy/Program Memorandum 151). August 18, 2021. https://www.ontario.ca/document/education-ontario-policy-and-program-direction/policyprogram-memorandum-151.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021c. “Next Steps for De-Streaming Grade 9 Course Codes and Descriptions for the 2022–23 School Year.” Memorandum, November 10, 2021. https://cpco.on.ca/index.php/download_file/view/8484/3092/.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021d. “Board Improvement and Equity Planning with Demographic Data.” Memorandum, September 20, 2021. https://cpco.on.ca/files/3316/3222/9212/MOE_-_Memo_re._Board_Improvement_and_Equity_Planning_with_Demographic_Data_-_September_20_2021.pdf.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021e. “Overview: New Board Improvement and Equity Plan (BIEP).” Accessed March 24, 2022. https://cpco.on.ca/files/2416/3222/9769/MOE_-_BIEP_Attachment_2_-_Overview_Two-Pager.pdf.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2022. “Education Funding, 2022–23.” Accessed April 6, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/education-funding-2022-23.

Ontario Teachers’ Federation. 2021. “Navigating De-Streaming: OTF and Affiliate Feedback on the Ministry of Education’s A Guide to De-streaming for Board Leaders, January 2021 Draft.” May. https://www.otffeo.on.ca/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/05/Navigating-De-Streaming-OTF-and-Affiliate-Feedback-on-the-Ministry-of-Education%E2%80%99s-A-Guide-to-De-streaming.pdf.

People for Education. 2007. “Class Sizes in Ontario Schools: The Effects of Provincial Class Size Policy on Ontario’s Elementary and Secondary Schools.” Toronto: People for Education. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://kipdf.com/class-sizes-in-ontario-schools-the-effects-of-provincial-class-size-policy-on-on_5ac6a7a11723dd36a020f1b2.html.

People for Education. 2013. “The Trouble with Course Choices in Ontario High Schools.” Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/People-for-Education-report-on-Applied-and-Academic-streaming.pdf.

People for Education. 2015. “Applied or Academic: High Impact Decisions for Ontario Students.” Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Applied-or-Academic-Report-2015.pdf.

People for Education. 2022. “A Perfect Storm of Stress: Ontario’s Publicly Funded Schools in Year Two of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Toronto: People for Education. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/AOSS-2021-22-Report-A-Perfect-Storm-of-Stress-March-24-2022-1.pdf.

Pichette, Jackie, Fiona Deller, and Julia Colyar. 2020. “De-streaming in Ontario: History, Evidence and Educator Reflections.” Toronto: The Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. https://heqco.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/De-streaming-in-Ontario_FORMATTED.pdf.

San Vicente, Ramon. 2015. “Sifting, Sorting, Selecting: A Collaborative Inquiry on Alternatives to Streaming in the TDSB.” Toronto: TDSB Equity and Inclusive Schools. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HQPZGsA6RguAeLcg5c_siVnsoTv79oCm/view.