Dr. Pamela Toulouse explores an Indigenous approach to quality learning environments and the Measuring What Matters competencies and skills. The paper draws out the research, concepts and themes from Measuring What Matters that align with Indigenous determinants of educational success. It expands on this work by offering perspectives and insights that are Indigenous and authentic in nature.

What matters in Indigenous education: Implementing a Vision Committed to Holism, Diversity and Engagement

Indigenous peoples’ experiences with education in Canada has been a contentious one. The focus from the outset of imposed, colonial-based education has centred on assimilation and/or segregation of Indigenous peoples from their communities and worldviews (National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health et al., 2009).

The history of education for Indigenous peoples in Canada has structural and societal roots mired in marginalization and subjugation. Today, the improved state of education for Indigenous peoples has its foundations in the resiliency of Indigenous communities and social justice movements advocating for inclusion and change (Iseke-Barnes, 2008; People for Education, 2013).

So, what is inclusion? Who are Indigenous peoples? What are the issues that face Indigenous peoples? How can education be reconceptualized to include Indigenous ways of knowing? And, why should we care? These are questions that will be examined throughout this paper.

People for Education, in its Measuring What Matters initiative, offers a body of research and student competencies that provides an opportunity to think critically about schooling success beyond test scores and standardized curriculum. It is a chance for those concerned with education to engage in conversations around what is important for the holistic development of our children, youth and world. These same themes and conversations are what guide Indigenous communities in their commitment to lifelong learning for their peoples (Nadeau & Young, 2006). Student achievement for Indigenous Nations is based on a birth to death continuum that is holistic and devoted to interconnectedness (Malott, 2007). The theme of holism resonates through the Measuring What Matters project, positing it in conceptual alignment with Indigenous epistemologies.

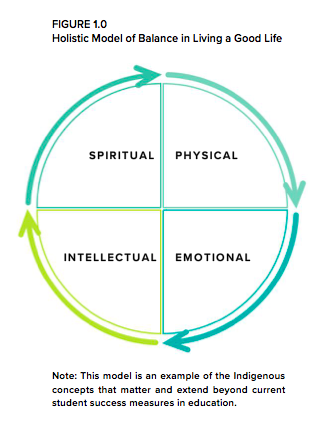

What matters to Indigenous peoples in education is that children, youth, adults and Elders have the opportunity to develop their gifts in a respectful space. It means that all community members are able to contribute to society (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and are physically, emotionally, intellectually and spiritually balanced (Iseke, 2010; Marule, 2012). This ability to give and ability to be well comes directly from the joining of the sacred and the secular. It is about fostering identity, facilitating well-being, connecting to land, honouring language, infusing with teachings and recognizing the inherent right to self-determination (Lee, 2015). Living a good life is what matters, and these thoughts are reflected in Figure 1.0. The physical refers to the body and comprehensive health of a being. The emotional is concerned with relationships to self, others (including non-humans) and the earth. The intellectual is based in natural curiosity and love for learning. The spiritual is the lived conscientiousness and footprint that a being leaves in this world.

This paper, What Matters In Indigenous Education: Implementing A Vision Committed To Holism, Diversity And Engagement, explores an Indigenous approach to quality learning environments and relevant competencies/skills.

It focuses on select work from People for Education and draws out the research, concepts and themes that align with Indigenous determinants of educational success. This paper also expands on this work by offering perspectives and insights that are Indigenous and authentic in nature. The three sections that frame and further develop this textual/symbolic journey are:

- Section One: Indigenous Issues, Indigenous Pedagogy And Educational Interconnections

- Section Two: Reflections On The Four Domains And Their Proposed Competencies And Skills

- Section Three: Embracing Indigenous Worldview And Quality Learning Environments

In conclusion, I thank you for reading this paper and hope that it creates a space for individual questions, group discussions and ultimately, collective action.

So, what are the facts? What is the current state of education for Indigenous peoples? Data from the 2011 National Household Survey (Statistics Canada) and the 2014 Auditor General Report of Ontario offers a measurable perspective to begin this section:

- 1,400,685 Indigenous people live in Canada, representing 4.3% of the total Canadian population.

- 851,560 identify as First Nations.

- 451,795 identify as Metis.

- 59,445 identify as Inuit.

- 301,425 Indigenous peoples live in the province of Ontario.

- 28% of the Indigenous population is from 0 to 14 years.

- 18.2% of the Indigenous population is from 15 to 24 years.

- Only 62% of Indigenous adults graduated from high school, compared to 78% of the general population.

- Only 39% of First Nations peoples living on-reserve graduated from high school.

- There is a 20% gap on Grade 3 EQAO reading results (provincial standard achievement) between Indigenous students (47%) and the general population (67%).

The numbers demonstrate that Indigenous peoples have a significantly younger population that is school age, and that the current measures of student achievement are not working. What is needed now is to clearly articulate the reasons for these gaps and find a more inclusive way to define student success.

The issues

Colonialism, racism, social exclusion, food insecurity, unemployment, poverty, limited access to housing, poor health and a myriad of other issues face Indigenous communities daily (People for Education, 2013; United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, n.d.) and confront Indigenous students to varying degrees. They are the result of policies, programs, people and politics that failed to honour the knowledge, values and skills of Indigenous Nations in Canada. Student achievement for communities of difference (like First Nations, Metis and Inuit ones) is a challenge for schools that do not have the capacity for change. Schools that are not supported with the tools and resources to address these inequities are placed at a critical disadvantage (Malott, 2007; Ontario Ministry of Education, 2009b). Thus the results for Indigenous students will continue to improve at a pace that is unfair and unacceptable.

So, how are these issues interconnected with education? They intersect in areas identified in The School Context Model: How School Environments Shape Students’ Opportunities To Learn (Bascia, 2014). Table 1.0 recognizes those intersections that reflect factors affecting Indigenous student achievement:

Table 1.0: Factors Affecting Indigenous Students and Their Learning

Classroom features |

Teacher communities |

| Diversity and differentiated learning is foundational

Learning is linked to students’ lives and experiences High expectations for all student coupled with differentiated assessment Classroom management is focused on community building and relationships |

Professional development is ongoing where data is a critical feature

Time and resources are allotted for teachers to plan together Relationships are collegial and student learning, as well as community, is a key underpinning Teachers are valued for their work and commitment |

Schools & climate |

External environment |

| School safety for all is a priority

Interpersonal relationships are positive and evolving Teaching and learning practices are evidence based Organizational structures support vision of inclusion Shared leadership is the reality between admin and staff Deconstructing the hidden curriculum |

Parental and community engagement plans honour difference

Culminating tasks for students are rooted in social change in the community Community and school events are integrated, shared and seamless Global citizenship and environmental stewardship connections |

Note. This table is a summary of the areas in Bascia’s paper that complement the diverse perspectives of Indigenous peoples regarding student achievement.

Classroom features, teacher communities, school climate and the external environment are broad concepts that are strongly interconnected. The concise descriptions in each of these areas, as listed in Table 1.0, provide the factors that are essential considerations in Indigenous student achievement. Learning outcomes, especially when more holistic definitions and interpretations are being considered, will be directly affected by these factors (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014). For example: under classroom features, we recognize that infusing diversity in learning is critical to student achievement. Indigenous ways of learning are part of that diversity and cannot be integrated if teacher professional development is inconsistent and there is limited time for collaborative planning. Also, the absence of parental engagement plans and linkages to community resources for Indigenous families become further barriers for students’ rightful attainment to balance/wellness (see Figure 1.0. Holistic Model of Balance in Living a Good Life). The issues are complex and will require solutions that are multilayered in their approach; however these measures are necessary for respectful inclusion of Indigenous students and their communities (National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health et. al, 2009).

Indigenous pedagogy

So, what is Indigenous pedagogy? Who are Indigenous peoples? We begin this section by exploring these terms and their associating nomenclature.

Indigenous: A term that does not have a universally accepted definition. However, the United Nations offers these characteristics; self-identification and acceptance as Indigenous peoples, historical continuity with settler societies, strong link to the land/traditional territories, distinct systems/ beliefs/languages/cultures, committed to maintaining the integrity of traditional lands and communities. (United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, n.d.)

Pedagogy: A term to describe the science of teaching, learning and evaluation. Refers to curriculum, methods, assessment, instruction, teacher/learner relationships and classroom structures. A broad field that is expanding in its definitions and scope (i.e. critical pedagogy; pedagogy of the oppressed). (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2007)

Aboriginal: A term found in Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982 that defines First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples as Aboriginals in Canada that possess certain treaty, existing and inherent rights. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2007)

First Nations: A term that is used to describe Aboriginal peoples in Canada that are not Metis or Inuit. Also, a general term to describe a community or communities that have similar identifiers (i.e. land – reserve; culture, language, traditions, history). There are 634 First Nations in Canada that speak 60 distinct languages. (Statistics Canada, 2011)

Metis: A term to describe people of mixed ancestry (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and are recognized as one of Canada’s Aboriginals under the Constitution Act of 1982. There are several Metis Nations in Canada that have shared histories, traditions and languages (i.e. Michif). (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2007)

Inuit: A term used to describe a group of Aboriginal people defined in the Constitution Act of 1982 that originally (and continue to) inhabit the northern parts of Canada. The Inuit have eight main ethnic groups and five distinct language dialects. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2007)

Self-Identification: A term used to describe how an individual names or appoints themselves. Typically refers to the group that we believe we belong to (i.e. Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, Louis Riel Metis, Inuk, Cree, Oji-Cree, Haida, Stolo, Dene, MicMac, Native). (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2007)

Cultural diversity truly describes the Indigenous peoples of Canada, and therefore no one-size-fits-all exists when it comes to curricular content. However, the pedagogical strategies of Indigenous peoples share some commonalties: connections to culture (the sacred), concrete to abstract/abstract to concrete examples of the subject expectations, mini-lessons with hands-on activities, differentiated instruction/assessment, connections to real life experiences, multileveled questions, storytelling, group talk (formal/informal), appropriate use of humour, and experiential activities (land-based) (Matilpi, 2012; Wyatt, 2009). The classroom environment, as facilitated by the teacher, also requires an approach with foundations in human rights education. It is critical that the space is welcoming and fosters consistency in expectations regarding respectful behavior, acceptance of difference and risk taking in learning. These have to be modeled by the teacher, as they set the tone for how relations between students and communities can grow together (Wallace, 2011).

Curriculum Content

The curriculum content and relevant cultural examples (i.e. specific Indigenous knowledge, values, skills) across subject areas in elementary/secondary need to begin with the local Indigenous Nations (Ledoux, 2006; Overmars, 2010). This is the starting place where respectful planning and inclusive education begins for the equity-based classroom. First, educators need to find out where their schools are located – Is it Anishinabe territory? Is it on the lands of Sagamok Anishnawbek? Is it in the Robinson-Huron Treaty area? Second, teachers need to connect with local Indigenous communities to facilitate the process of infusing authentic experiences and genuine content into the classroom curriculum, and finding out how these Nations self-identify. Third, the integration of more provincial and national resources that are Indigenous and more broadly focused are encouraged. How does one do this? Where does an educator begin? The following resources may be helpful in exploring the possibilities for including Indigenous content in the curriculum:

- Indigenous Leads/Coordinators with Various Ontario School Boards

- Ontario Indigenous Friendship Centres

- Chiefs of Ontario office

- Ontario Native Education Counsellors Association

- Metis Nation of Ontario

- Inuit of Ontario

- Indigenous Publications from Kindergarten to Post-Secondary

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

Educational interconnections

Boucher (2015) in What Matters In French-Language Schools: Implementing A Broader Vision For Student Achievement In A Minority Setting offers a perspective that aligns with Indigenous definitions of student achievement.

Table 1.1 summarizes the key concepts that reflect the educational interconnections between Francophone and Indigenous communities.

Sharing influence, interpersonal relationships, raising awareness/taking action, mobilizing, creating meaning and making learning real are vital components in Indigenous learner success. The classroom experience for students needs to begin with a shared vision of what counts as learning. This is where the physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual domains of holistic education (Figure 1.0) are to be respected and realized. Children and youth require a safe space that affirms their diversity and identity; where they can be honoured with cultural, linguistic and affirming models that support them. Self-realization and being valued (knowledge, skills) is a key tenet of Francophone communities, and this too is the goal for Indigenous peoples in education. Self-determination and understanding the forces that have shaped where we have come from are essential determinants in Indigenous conceptions of student success (Ismail & Cazden, 2005).

Table 1.1 Pedagogy Honouring Francophone and Indigenous Learners

Sharing

|

Interpesonal relationships |

Raising awareness and taking action |

| Decisions about learning must reflect the full range of diverse points of view. | A healthy environment allows students to make suggestions and express feelings about language and culture. | Understand the issues that shape our lives and become engaged to claim our rightful place in society. |

Mobilizing |

Creating Meaning |

Making Learning Real & Relevant to the Present Moment |

| Mobilizing is a process that triggers a person’s self-determination and respect for cultural & linguistic diversity. | To bring balance to the experiences of young people, we need to offer strong cultural models. | Value the prior knowledge and skills of students and educators to assist them on the path to self-realization. |

Note. This table is a summary of the areas in the work of Boucher that compliment the diverse perspectives of Indigenous peoples regarding respectful pedagogy in schools.

In conclusion, Indigenous issues, Indigenous pedagogy and respective educational interconnections complement the holistic aspects of student achievement described in Measuring What Matters. Communities of difference share a vision of success that is highly valuable for all students – a vision based on the recognition that identity, culture, language and worldview are equally critical to literacy, numeracy and standardized notions of assessment.

I grew up on a First Nation in northern Ontario. I am Ojibwe and a woman. I have been very fortunate in my life to learn about my own teachings and all the beautiful gifts that Indigenous peoples have given to the world. It is important that I self-identify in this section, as the cultural lens that I am referencing is one that comes from my community. There are a multitude of diverse Indigenous Nations on Turtle Island (North America) and my Nation is only one of them. While the heterogeneity of Indigenous peoples is vast, the concept of holism and education as lifelong is a worldview that is shared by all (Castagno & Brayboy, 2008; Overmars, 2010). In Measuring What Matters, the papers focused on health, social/emotional wellness, citizenship and creativity resonate with Indigenous notions of teaching/learning. My intent is to explore these papers using a form of analysis that is rooted in the teachings of the medicine wheel. This is the theoretical framework through which I can make sense of and be respectful of both Indigenous epistemology and the authors of these diverse papers.

So, how do we proceed? Where do these papers fit within the medicine wheel? What are the underlying teachings that connect these distinct cultural domains to the four papers? We begin with an understanding of the teachings first.

The medicine wheel

The medicine wheel is also known as the living teachings. It is a circle of life that is continuous and never-ending. It demonstrates that everything is connected and everything is sacred. All of life is equal. All of life is deserving of respect, care and love. The entry point for discussion is the physical domain. This is where birth of children is located. It is also symbolic of spring, the rising of the sun and the direction of the east. The emotional domain is where adolescence is located. It is also where summer resides, where the sun is at its highest and the direction of south is represented. The intellectual domain is where adulthood makes its home. It is where the season of fall arises, where the sun sets and the direction of the west sits. The spiritual domain is where our Elders/Elderly journey to, it is where winter is steadfast, where the moon makes her appearance and the direction of the north is situated. Each domain reflects aspects of a human being that makes them whole; the east is the physical, the south is the emotional, the west is the intellectual and the north is the spiritual. Balance in each is key. Disrupt the balance and each area of life is affected.

The medicine wheel is also known as the living teachings. It is a circle of life that is continuous and never-ending. It demonstrates that everything is connected and everything is sacred. All of life is equal. All of life is deserving of respect, care and love. The entry point for discussion is the physical domain. This is where birth of children is located. It is also symbolic of spring, the rising of the sun and the direction of the east. The emotional domain is where adolescence is located. It is also where summer resides, where the sun is at its highest and the direction of south is represented. The intellectual domain is where adulthood makes its home. It is where the season of fall arises, where the sun sets and the direction of the west sits. The spiritual domain is where our Elders/Elderly journey to, it is where winter is steadfast, where the moon makes her appearance and the direction of the north is situated. Each domain reflects aspects of a human being that makes them whole; the east is the physical, the south is the emotional, the west is the intellectual and the north is the spiritual. Balance in each is key. Disrupt the balance and each area of life is affected.

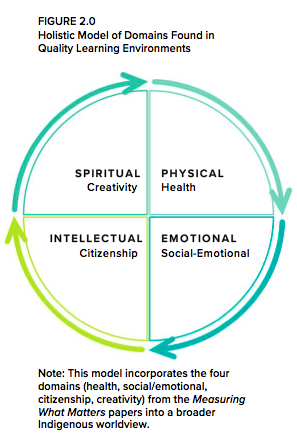

The medicine wheel has a direct relationship to quality learning environments that extend beyond literacy, numeracy and standardized curriculum. It is based in holistic learning environments that are inclusive of the preceding, but, also value the physical (health), the emotional (social-emotional), the intellectual (citizenship) and the spiritual (creativity). Figure 2.0 provides a symbolic model of how the discussion surrounding the four Measuring What Matters papers will proceed. As reflected in the living teachings, this next section will be organized with the physical as the beginning and the spiritual as the concluding piece. The emotional and intellectual take their respective (and equally important) places in between.

The Physical Aspect and Health Competencies/Skills

Ferguson and Power (2014) in Broader Measures of Success: Physical and Mental Health in Schools state that,

Both physical and mental health promotion are important from individual, social, and economic perspectives. Because of their centrality in the lives of children and youth, schools have been widely regarded as places for effective promotion and interventions in physical and mental health (p. 3).

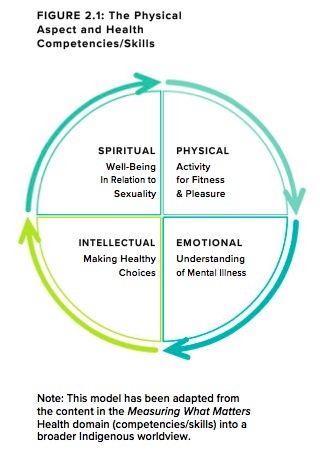

These words resonate with Indigenous conceptions of what counts by focusing on the whole learner. Physical and mental health are integral aspects of the medicine wheel (Figure 2.0.) and cannot be separated. The health of a human being is directly interrelated to their wellness and their capacity to develop in all areas of life (Anderson et al., 2011). As children and youth spend large amounts of time in school, it makes sense that physical and mental health should be a valid measure of school success. With this in mind, the Comprehensive School Health model (i.e. teaching/learning, environments, policies, community partnerships), which includes mental health literacy, sexuality education and resiliency programs, aligns with the holistic teachings of Indigenous peoples (National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health et al., 2009). So, what does this look like in the day-to-day lives of our children and youth? How do children/ youth show competency in these areas of health? Figure 2.1. offers a view that integrates the teachings of the medicine wheel with the work of People for Education in their Draft Competencies and Skills paper.

While all of the health competencies and skills identified in People for Education’s paper are critical, there are certain ones that are foundational in Indigenous worldviews. Therefore, each area from Figure 2.1 will be concisely presented with the key competency/ skill listed and/or edited to ensure that it is inclusive of Indigenous communities. It is important to note that this is being done at a macro level and needs to be vetted by individual Indigenous Nations in Canada as part of their right to self-determination in education (Knowles, 2012).

While all of the health competencies and skills identified in People for Education’s paper are critical, there are certain ones that are foundational in Indigenous worldviews. Therefore, each area from Figure 2.1 will be concisely presented with the key competency/ skill listed and/or edited to ensure that it is inclusive of Indigenous communities. It is important to note that this is being done at a macro level and needs to be vetted by individual Indigenous Nations in Canada as part of their right to self-determination in education (Knowles, 2012).

The Physical – Activity For Fitness And Pleasure

- Students develop physical fitness and movement skills needed to participate in diverse activities; fully understanding that the body is a sacred entity.

The Emotional – Understanding of Mental Illness

- Students are informed and understand that mental health issues are a collective concern and that cultural knowledge is a critical support.

The Intellectual – Making Healthy Choices

- Students have a sense of personal responsibility for their own wellness (activity, eating, sleeping, assessing risks) and humbly share these strategies with others.

The Spiritual – Well-Being in Relation to Sexuality

- Students develop and appreciate their own and others sexual identities; knowing that sexuality is a healthy part of being a human and is to be expressed respectfully.

The Emotional Aspect and Social-Emotional Competencies/Skills

Shanker (2014) in Broader Measures of Success: Social/Emotional Learning states that,

“Instead of seeing reason and emotion as belonging to separate and independent faculties (the former controlling the latter), they [a multitude of researchers] argued that social, emotional and cognitive processes are all bound together in a seamless web” (p. 1).

This recognition of interconnectedness as a primary concept in learning and emotional development runs parallel to Indigenous worldviews (Carriere, 2010; Iseke, 2010). Elders, Metis Senators and knowledge keepers in First Nations, Metis and Inuit communities have been relaying these teachings since time immemorial. Traditional education in Indigenous communities valued holism in learning; embedded in this approach is the equity between applied scholarship and emotional intelligence (Lee, 2015; Wildcat et al., 2014). Children, youth, adults and our elderly engaged in a form of schooling that was cooperative, collective and conscientious. Shanker (2014) reflects these Indigenous concepts through exploring the components and impacts of the American-based Child Development Project (i.e. community building activities, engaging curriculum, cooperative learning, literacy development). This preceding endeavour, combined with the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) and the Positive Action Program (PAP), build upon Indigenous conceptions of what matters in social-emotional schooling for students.

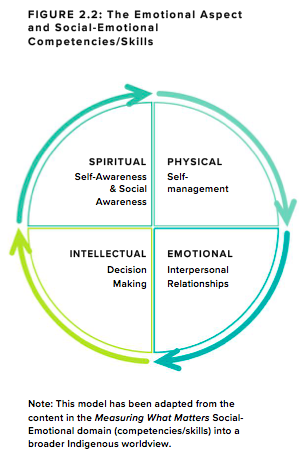

With these thoughts in our minds, we turn to Figure 2.2, which captures the complex competencies/skills that Indigenous learners exhibit in expanded notions of student achievement. Once again, the social-emotional competencies and skills identified in the People for Education paper are all critical; however there are particular ones that best reflect Indigenous worldviews. These will be identified and edited to be respectful of cultural teachings and the research emerging from People for Education.

With these thoughts in our minds, we turn to Figure 2.2, which captures the complex competencies/skills that Indigenous learners exhibit in expanded notions of student achievement. Once again, the social-emotional competencies and skills identified in the People for Education paper are all critical; however there are particular ones that best reflect Indigenous worldviews. These will be identified and edited to be respectful of cultural teachings and the research emerging from People for Education.

The Physical – Self-Management

- Students develop skills for managing their own learning, emotions and behaviours; firmly rooted in the understanding that their actions affect their growth and others.

The Emotional – Interpersonal Relationships

- Students cultivate and maintain healthy relationships with the self, others and the earth; acknowledging the sacredness of all these beings that surround them.

The Intellectual – Decision Making

- Students internalize and implement appropriate strategies to solve a multitude of issues/problems, with personal humility and collective integrity at the heart of it.

The Spiritual – Self-Awareness & Social Awareness

- Students grow in their cultural/personal identities and their ability to reflect on their communities’ teachings as critical to being a respectful member of the world.

The Intellectual Aspect and Citizenship Competencies/Skills

Sears (2014) in Measuring What Matters: Citizenship Domain states that,

Civic education begins at home and continues out into the community. Again, evidence indicates civil society involvements of various kinds, both those connected to schooling and those not, profoundly shape young people’s civic knowledge, values, and sense of efficacy (p. 4).

Understanding how history shaped our societies and having a commitment to service learning are also an integral part of being an active citizen. This is consistent with traditional Indigenous perspectives on citizenship, where each individual is nurtured and positioned to develop their gifts as a human being (Lee, 2015; Nadeau & Young, 2006). This approach was/is supported through cultural teachings and guided by various knowledge keepers in the community (John, 2009). Each person was/is taught about traditions and their familial role as part of a greater collective. Fundamental to this type of citizenship education was/is understanding the history and impacts of Indigenous and settler governments on all peoples. I use past and present tense here intentionally. Traditional forms of Indigenous government and their teachings were directly affected by colonialism and the imposition of oppressive policies. Although there is a resurgence and return to culture/language for Indigenous peoples, it is happening to various degrees across the country (Overmars, 2010; Wyatt, 2009).

The concept of a civic profile is familiar to First Nations, Metis and Inuit Nations, and focuses on what a good citizen does as a contributing member to that society. Sears (2014) takes this notion further by stating that voting is not a primary indicator of civic duty. In fact he emphasizes that, “a well-balanced democratic society requires a range of civic engagement, and since citizens simply cannot spend the requisite time to engage in all areas…they would be better to focus their participation in areas where they have interest and ability to make the most significant contribution” (p. 18). This thought, based in evidence, aligns with the activities of an Indigenous citizen.

With this, we turn our attention to Figure 2.3, which concisely summarizes the draft competencies and skills identified in the citizenship section of the People for Education paper. What follows this model are critical statements that reflect Indigenous conceptions of citizenship.

The Physical – Civic Knowledge

- Students learn about their own traditional forms of government and further understand settler governments and their associative rights/responsibilities.

The Emotional – Civic Dispositions

- Students exemplify the values of their respective Nations and utilize these to become effective citizens in two worlds (Indigenous and non-Indigenous).

The Intellectual – Civic Skills

- Students acquire culturally-based mediation and problem solving skills as a means to appreciate diverse points of view; knowing when to act (and when not to act).

The Spiritual – Civic Engagement

- Students engage in human rights and social justice movements that reflect the integrity of all beings and are consistent with their distinct cultural beliefs.

The Spiritual Aspect and Creativity Competencies/Skills

Upitis (2014) in Creativity: The State Of The Domain reveals that,

New ways of thinking and acting are needed to alleviate the impact of human life on our planet, approaches that will call for creativity and innovation from all disciplines. Over the next few decades, schools will have a crucial role to play. In schools where creativity is fostered, students will develop the intellectual tools to innovate, and also, the passion to direct their skills to problems of global concern (p. 6).

Stewardship of the earth and recognition that all of life (and the universe) is interrelated is a key underpinning of Indigenous worldview (Marin & Bang, 2015). Invention and learning are also factors in the resiliency of Indigenous peoples across the Nation (Marule, 2012). The concept that creativity, the sacred, and personal responsibility are interrelated is not a new idea to First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples (Martin & Garrett, 2010). Therefore, it makes sense that an expanded definition of creativity be included as a measure of success in schools. Student achievement would be amiss if it did not count the range of creative thoughts/practices as essential learning outcomes.

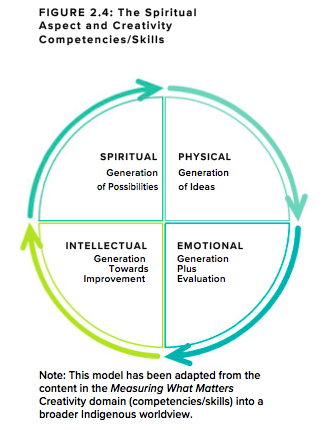

Schools that are resourced to provide opportunities in critical thinking, student-directed learning, integrated curriculum, and community partnerships are steps towards being inclusive of creativity. However, a focused program on the multiple levels, processes and outcomes of creative thought is needed to “contribute to [all] lives that are joyful, productive, meaningful, and prosperous” (p. 3). So, what does this look like? How do students demonstrate creativity? Figure 2.4 provides this view with a concise summary of the draft competencies and skills identified in the creativity section of the People for Education paper. Following this model are critical statements that reflect Indigenous concepts of creativity.

Schools that are resourced to provide opportunities in critical thinking, student-directed learning, integrated curriculum, and community partnerships are steps towards being inclusive of creativity. However, a focused program on the multiple levels, processes and outcomes of creative thought is needed to “contribute to [all] lives that are joyful, productive, meaningful, and prosperous” (p. 3). So, what does this look like? How do students demonstrate creativity? Figure 2.4 provides this view with a concise summary of the draft competencies and skills identified in the creativity section of the People for Education paper. Following this model are critical statements that reflect Indigenous concepts of creativity.

The Physical – Generation of Ideas

- Students welcome and discover thoughts, impressions and information from a multitude of senses and teachers (the secular, the sacred, the formal, the informal).

The Emotional – Generation plus Evaluation

- Students explore their natural curiosity about the world and universe through the selective integration of this knowledge into their life journeys.

The Intellectual – Generation towards Improvement

- Students assess their cultural gifts, creative ideas, artistic work and relative interactions/outputs with a focus on growth and potential change.

The Spiritual – Generation of Possibilities

- Students engage in many opportunities to dream and visualize with the intent of realizing and actualizing what is in their mind, heart and spirit.

In conclusion, the four papers describing the domains (physical and mental health, social-emotional, citizenship, creativity) have particular focuses that compliment Indigenous worldviews. The notions of holism, engagement, diversity, action and respect are reflected throughout. The proposed competencies and skills are also Indigenous compatible in terms of expanding current measurable outcomes beyond literacy, numeracy and standardized curriculum. The idea that schooling, pedagogy and assessment can honour the whole child is certainly a welcome change in our complex world.

What is a quality learning environment? How do Indigenous worldviews reflect this concept? Are there particular components that make up this type of teaching/learning setting? The final section of this paper will address these questions through the integration of Indigenous perspectives and select research from People for Education.

In the inaugural paper of the Measuring What Matters (2013) initiative, this statement captures the immediacy and necessity of reframing what counts as student achievement in schools,

Although current approaches to measuring and reporting on educational quality are useful both locally and internationally, they are, for the most part, limited to literacy and numeracy achievement. These measures are necessary but not sufficient. A growing chorus of voices is asking, “Isn’t education about more than that? Don’t we need healthy kids who can think; who are innovative and will grow up to be engaged citizens?” (People for Education, p. 8)

Indigenous communities across Canada have been asking these same questions and confronting these same issues since non-Indigenous forms of schooling came to dominate the K to 12 continuum ((Iseke-Barnes, 2008). Educational quality for First Nations, Metis and Inuit learners is centred on a holistic method that considers the entirety of a being (Matilpi, 2012). This approach is best represented in Figure 3.0, which posits the student in the middle; interacting with/being affected by four key conditions that are critical to learning (i.e. classroom, school, community, globe).

Indigenous communities across Canada have been asking these same questions and confronting these same issues since non-Indigenous forms of schooling came to dominate the K to 12 continuum ((Iseke-Barnes, 2008). Educational quality for First Nations, Metis and Inuit learners is centred on a holistic method that considers the entirety of a being (Matilpi, 2012). This approach is best represented in Figure 3.0, which posits the student in the middle; interacting with/being affected by four key conditions that are critical to learning (i.e. classroom, school, community, globe).

The needs of the whole student is the base consideration in Indigenous descriptions of education, and the guiding principle in Indigenous conceptions of student achievement. What matters to Indigenous peoples is that each member of the community is nurtured and challenged in respectful ways. This form of teaching/ learning is done through the honouring of the culture, the teachings, the languages, and the gifts of each Nation (Hinton, 2011; Zitzer-Comfort, 2008). It is critical to understand that in our current school system, this vision is affected by particular interconnecting forces: the classroom environment, the school itself, the community (Indigenous & non-Indigenous) and the state of the earth (the globe). Each of these areas will be further explored with the intent that aspects of Indigenous worldview are aligned with inclusive definitions of quality learning environments.

The classroom

What is a classroom? It is the space where an exchange of knowledge takes place. It can happen inside a building. It can happen outside of a building. It has students and teachers that are involved in a variety of learning relationships. It is also a place where the curriculum (mandated and hidden) provides a structure (flexible and inflexible at the same time). It is also where pedagogy can empower or disempower students (Malott, 2007). The classroom is a microcosm of society that has real outcomes (positive and negative) for multiple groups of people (King, 2002).

The conditions in the classroom that foster Indigenous learners are varied. However, these particular edited statements from the Draft Competencies and Skills (n.d.) capture the critical factors necessary for Indigenous inclusive spaces:

- The classroom is welcoming and student voice/experiences are recognized as integral to the construction of active knowledge.

- Expectations for students are high, realistic, flexible, and supported by teacher/s, peers and other critical friends.

- Classroom activities are culturally relevant, differentiated, and promote exploration, imagination, and creative action.

- Student learning is expressed in a variety of forms that honour diversity and challenge students to try a multiplicity of methods.

The school

There are approximately 15,500 schools in Canada; of which 10,100 are elementary, 3400 are secondary and 2000 are mixed (Council of Ministers of Education Canada, 2015). In Ontario, there are 3974 elementary schools and 919 secondary (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2015). Every school board in Ontario has at least some Indigenous students attending Kindergarten to Grade 12 (People for Education, 2013). The conditions that facilitate Indigenous inclusion in school are as follows (adapted from the Draft Competencies and Skills, n.d.):

- School leadership is shared with the teachers, students, the community, and education advocates, with trust and collaboration at the core.

- The school is an open learning space where community members with diverse expertise work with students and staff.

- School based structures are in place to provide support for students (and their families) with a variety of challenges/issues.

- Professional learning for teachers and staff is valued and integrated in evidence- based practices focused on access/equity.

The community

Standardized definitions of community relegate this term to being a noun and describe it as “people living in one particular area because of their common interests, social group or nationality” (Cambridge English Dictionary Online, 2015). Indigenous definitions of community identify particular participants/ conditions, and these are often verb-based (Carriere, 2010). These descriptions take on a more holistic approach, and are inclusive of all beings (humans, plants, animals, seen, unseen) and the interconnections that exist amongst them. The latter definition is more relevant for a cross-cultural understanding of the community factors affecting expanded notions of student achievement.

The competencies that are fundamental to community and student success are (adapted from Draft Competencies and Skills, n.d.):

- Meaningful school-community partnerships and agreements are based in time, reciprocity, trust, respect, relevance, and actualized plans.

- Programs that de-stigmatize mental illness, prevent bullying, and prevent substance abuse are implemented with culturally relevant tools/resources.

- Students develop enriched definitions of community and commit to volunteering in action-oriented projects that reflect those expanded descriptions.

- Monitoring and reviewing of domain competencies in relation to student learning and school practices involve Elders, Metis Senators and knowledge keepers.

The globe

Global education with a decolonization focus is best described as, “asking new and difficult questions concerning the erasures, negations, and omissions of histories, identities, representations, cultures, and practices [in schools]” (Sefa Dei, 2014, p. 10). This definition aligns with aspects of Indigenous conceptions of global education; however, the addition of recognizing and living with the earth as our mother will be added here (Overmars, 2010). A quality learning environment that honours global perspectives has these competencies reflected within it:

- Students understand and “confront the conditions and unequal power relations that have created unequal advantage and privilege among nations” (Sefa Dei, 2014, p. 10).

- Promotion of Indigenous earth knowledge and sacred connections to land as fundamental to “developing a sense of purpose…[life meaning]…and social existence” (Sefa Dei, 2014, p. 10).

- Integrating the “idea of pursuing schooling and education as a communal resource intended for the good of humanity” (Sefa Dei, 2014, p. 10).

- Connections with learners across the globe to share experiences and discuss the challenges that these generations face; with creative action as an outcome.

In conclusion, student achievement needs to be reconceptualized to include the physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual aspects of the whole being. This view is supported through examining respectful conditions/competencies that fully consider the impacts of the classroom, the school, the community and the globe. Indigenous epistemologies and Elder/Metis Senator knowledge can facilitate this much-needed educational change (Lavoie et al., 2012).

The questions,

- What is inclusion?

- Who are Indigenous peoples?

- What are the issues that face Indigenous peoples?

- How can education be reconceptualized to include Indigenous ways of knowing? And,

- Why should we care?

began this paper and close this textual/symbolic journey together. What Matters In Indigenous Education: Implementing A Vision Committed To Holism, Diversity And Engagement is quite simply, the students. This paper is for those young spirits that walk to school, get on a bus, ride the subway, commute and/or reside in educational places that currently (or need to) honour them further. Meaning that we need to move beyond just considering achievement in schooling and look at the real implications and lived outcomes (King, 2008). Indigenous peoples have known and have been experiencing this since time immemorial.

Meegwetch and thank you for listening.

Anderson, J. F., Pakula, B., Smye, V., Peters (Siyamex), V., & Schroeder, L. (2011). Strengthening Aboriginal Health through a Place-Based Learning Community. Journal Of Aboriginal Health, 7(1), 42-51.

Bascia, N. (2014). The School Context Model: How School Environments Shape Students’ Opportunities to Learn. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Boucher, M. (2015). Focus on the French-language school. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: March, 2015.

Carriere, J. (2010). Editorial: Gathering, Sharing and Documenting the Wisdom Within and Across our Communities and Academic Circles. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 5-7.

Castagno, A. E., & Brayboy, B. J. (2008). Culturally Responsive Schooling for Indigenous Youth: A Review of the Literature. Review Of Educational Research, 78(4), 941-993.

Community [Def. 1]. (2015). In Cambridge English Dictionary Online. Retrieved December 14, 2015, from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/community

Council of Ministers of Education Canada,. (2015, December 2). Education in Canada: An Overview. Retrieved from http://www.cmec.ca/299/Education-in-Canada-An-Overview/

Ferguson, B. and Power, K. (2014). Broader Measures of Success: Physical and Mental Health in Schools. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Hinton, L. (2011). Language revitalization and language pedagogy: new teaching and learning strategies. Language & Education: An International Journal, 25(4), 307-318. doi:10.1080 /09500782.2011.577220

Iseke, J. M. (2010). Importance of Métis Ways of Knowing in Healing Communities. Canadian Journal Of Native Education, 33(1), 83-97.

Iseke-Barnes, J. M. (2008). Pedagogies for Decolonizing. Canadian Journal Of Native Education, 31(1), 123-148.

Ismail, S. M., & Cazden, C. B. (2005). Struggles for Indigenous Education and Self-Determination: Culture, Context, and Collaboration. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 36(1), 88-92.

John, T. A. (2009). Nutemilarput, Our Very Own: A Yup’ik Epistemology. Canadian Journal Of Native Education, 32(1), 57-72.

King, C. R. (2008). Teaching Intolerance: Anti-Indian Imagery, Racial Politics, and (Anti) Racist Pedagogy. Review Of Education, Pedagogy & Cultural Studies, 30(5), 420-436. doi:10.1080/10714410802426574

King, C. R. (2002). Defensive dialogues: Native American mascots, anti-Indianism, and educational institutions. Simile, 2(1), N.PAG.

Knowles, F. E. (2012). Toward emancipatory education: an application of Habermasian theory to Native American educational policy. International Journal Of Qualitative Studies In Education (QSE), 25(7), 885-904. doi:10.1080/09518398.2012.720735

Lavoie, C., Sarkar, M., Mark, M., & Jenniss, B. (2012). Multiliteracies Pedagogy in Language Teaching: An Example from an Innu Community in Quebec. Canadian Journal Of Native Education, 35(1), 194-210.

Ledoux, J. (2006). Integrating Aboriginal Perspectives Into Curricula: A Literature Review. Canadian Journal Of Native Studies, 26(2), 265-288.

Lee, T. S. (2015). The Significance of Self-Determination in Socially, Culturally, and Linguistically Responsive (SCLR) Education in Indigenous Contexts. Journal Of American Indian Education, 54(1), 10-32.

Malott, C. S. (2007). Chapter 4: Critical Pedagogy in Native North America: Western and Indigenous Philosophy in the Schooling Context. In , Call to Action: An Introduction to Education, Philosophy, & Native North America (pp. 117-151).

Marin, A., & Bang, M. (2015). Designing Pedagogies for Indigenous Science Education: Finding Our Way to Storywork. Journal Of American Indian Education, 54(2), 29-51.

Martin, K. J., & Garrett, J. J. (2010). Teaching And Learning With Traditional Indigenous Knowledge In The Tall Grass Plains. Canadian Journal Of Native Studies, 30(2), 289-314.

Marule, T. O. (2012). Niitsitapi Relational and Experiential Theories in Education. Canadian Journal Of Native Education, 35(1), 131-143.

Matilpi, M. (2012). In Our Collectivity: Teaching, Learning, and Indigenous Voice. Canadian Journal Of Native Education, 35(1), 211-220.

Nadeau, D., & Young, A. (2006). Educating Bodies for Self-Determination: A Decolonizing Strategy. Canadian Journal Of Native Education, 29(1), 87-101.

National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health, Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health Inequalities and Social Determinants of Aboriginal Peoples Health. 2009.

Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. (2015). Chapter 4 – Section 4.05. – Education of Aboriginal Students. Toronto, ON: Same as Author.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2015, December 2). Education Facts, 2014-2015* (Preliminary). Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/educationFacts.html

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Achieving Excellence. A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario. Retrieved on December 1, 2015 at http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/

Ontario Ministry of Education (2009b). Realizing the Promise of Diversity. Ontario’s Equity and Inclusive Education Strategy. Retrieved on December 1, 2015 at http://www.edu. gov.on.ca/eng/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2007). Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Education.

Overmars, D. (2010). Indigenous Knowledge, Community and Education in a Western System: An Integrative Approach. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(2), 88-95.

People for Education. (n.d.). Measuring What Matters: Draft Competencies. Retrieved on December 12, 2015 at http://www.peopleforeducation.ca/

People for Education (2013). Broader Measure of Success: Measuring What Matters. Retrieved on December 5, 2015 at http://www.peopleforeducation.ca/

People for Education (2013). First Nations, Metis and Inuit Education: Overcoming gaps in provincially funded schools. Retrieved on December 2, 2015 at http://www. peopleforeducation.ca/

Sears, A. (2014). Measuring What Matters: Citizenship Domain. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014

Sefa Dei, G.J. (2014). Reflecting on Global Dimensions of Contemporary Education. In D. Montemurro, M. Gambhir, M. Evans & K. Broad (Eds.), Inquiry into Practice: Learning and Teaching Global Matters in Local Classrooms (p. 9-11). Toronto, ON: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Shanker, S. (2014). Broader Measures for Success: Social/Emotional Learning. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014

Statistics Canada. (2011). Aboriginal Demographics from the 2011 National Household Survey. Retrieved on December 1, 2015 at https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/ eng/1370438978311/1370439050610

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (n.d.). Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Voices, Fact Sheet. New York, NY: Same as Author.

Uptis, R (2014). Creativity; The State of the Domain. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014

Wallace, R. (2011). Power, Practice And A Critical Pedagogy For Non-Indigenous Allies. Canadian Journal Of Native Studies, 31(2), 155-172.

Wildcat, M., McDonald, M., Irlbacher-Fox, S., & Coulthard, G. (2014). Learning from the land:

Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), I-XV.

Wyatt, T. (2009). The Role of Culture in Culturally Compatible Education. Journal Of American Indian Education, 48(3), 47-63.

Zitzer-Comfort, C. (2008). Teaching Native American Literature: Inviting Students to See the World through Indigenous Lenses. Pedagogy, 8(1), 160-170. doi:10.1215/15314200-2007-031

People for Education – working with experts from across Canada – is leading a multi-year project to broaden the Canadian definition of school success by expanding the indicators we use to measure schools’ progress in a number of vital areas.

Author

Dr. Pamela Toulouse

Researcher, Indigenous pedagogy & lifelong learning

The Measuring What Matters reports and papers were developed in partnership with lead authors of each domain paper. Permission to photocopy or otherwise reproduce copyrighted material published in this paper should be submitted to People for Education at [email protected].

Document citation

This report should be cited in the following manner:

Toulouse, P. (2016). What Matters in Indigenous Education: Implementing a Vision Committed to Holism, Diversity and Engagement. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: March, 2016.

We are immensely grateful for the support of all our partners and supporters, who make this work possible.

Annie Kidder, Executive Director, People for Education

David Cameron, Research Director, People for Education

Charles Ungerleider, Professor Emeritus, Educational Studies, The University of British Columbia and Director of Research, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Lindy Amato, Director, Professional A airs, Ontario Teachers’ Federation

Nina Bascia, Professor and Director, Collaborative Educational Policy Program, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Ruth Baumann, Partner, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Kathy Bickmore, Professor, Curriculum, Teaching and Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Michelle Boucher, University of Ottawa, Advisors in French-language education and Ron Canuel, President & CEO, Canadian Education Association

Ruth Childs, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Jean Clinton, Associate Clinical Professor, McMaster University, Dept of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences

Gerry Connelly, Director, Policy and Knowledge Mobilization, The Learning Partnership

J.C. Couture, Associate Coordinator, Research, Alberta Teachers’ Association

Fiona Deller, Executive Director, Policy and Partnerships, Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario

Kadriye Ercikan, Professor, Measurement, Evaluation and Research Methodology, University of British Columbia

Bruce Ferguson, Professor of Psychiatry, Psychology, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto; Community Health Systems Research Group, SickKids

Joseph Flessa, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Joan M. Green, O.Ont., Founding Chief Executive O cer of EQAO, International Education Consultant

Andy Hargreaves, Thomas More Brennan Chair, Lynch School of Education, Boston College Eunice

Eunhee Jang, Associate Professor, Department of Applied Psychology & Human Development, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Christopher Kotz, Senior Policy Advisor, Ontario Ministry of Education

Ann Lieberman, Stanford Centre for Opportunity Policy in Education, Professor Emeritus, Teachers College, Columbia University

John Malloy, Director of Education, Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board

Roger Martin, Premier’s Chair on Competitiveness and Productivity, Director of the Martin Prosperity Institute, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Ayasha Mayr Handel, Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services

Catherine McCullough, former Director of Education, Sudbury Catholic District School Board

Robert Ock, Healthy Active Living Unit, Health Promotion Implementation Branch, Health Promotion Division, Ontario Ministry of Health

Charles Pascal, Professor, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Jennifer Riel, Associate Director, Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Joanne Robinson, Director of Professional Learning, Education Leadership Canada, Ontario Principals’ Council

Bruce Rodrigues, Chief Executive Officer, Ontario Education Quality and Accountability Office

Pasi Sahlberg, Director General, Centre for International Mobility and Cooperation, Finland

Alan Sears, Professor of social studies and citizenship education, University of New Brunswick

Stuart Shanker, Research Professor, Philosophy and Psychology, York University; Director, Milton and Ethel Harris Research Initiative, York University; Canadian Self-Regulation Initiative

Michel St. Germain, University of Ottawa, Advisors in French-language education

Kate Tilleczek, Professor and Canada Research Chair, Director, Young Lives Research, University of Prince Edward Island

Rena Upitis, Professor of Education, Queen’s University

Sue Winton, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Education, York University and former Early Learning Advisor to the Premier Deputy Minister of Education