A summary of the findings from the initial public consultations and an outline of the work done to identify the five domain areas and conditions for quality learning environments.

I am thrilled to learn about this initiative. While I believe, whole-heartedly, that literacy and numeracy are of great importance, we have neglected the other areas that make a person and a society whole and full.

– Secondary school teacher

According to Stuart Shanker, there has been a revolution in educational thinking in the last decade, but the goals and measures of success that we set for our schools have not kept up.

In answer to this problem, People for Education has launched Measuring What Matters, a multi-year initiative to develop a new set of measures and performance standards for schools that include indicators for the broad range of skills that graduates – and our society – really need.

This ground-breaking initiative, led by People for Education researchers and public engagement experts, includes Ontario’s Ministries of Education, Health, and Children and Youth Services, a number of Canadian universities, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group, the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario and the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO), Ontario’s Principals’ councils and other education stakeholders, as well as the broader public. It is also part of an international initiative led by UNESCO and the Brookings Institute to build consensus about appropriate quality measures for schools.

The goal of Measuring What Matters is to create a set of reliable, valid measures that are publicly understandable, educationally useful and reflect the broad skills students will need in the workforce and to take their place as engaged citizens.

The initiative includes 4 phases:

- research and public consultations;

- review of Ontario curriculum and policy, standard setting and outreach to Ontario schools;

- development of measurement instruments and pilot testing in a range of Ontario elementary and secondary schools; and

- a series of provincial conferences leading to a national symposium.

In today’s management culture, what gets measured, gets done.

– School board staff member and parent

Over the course of 2013/14, People for Education conducted public outreach through a widely-publicized survey distributed across the province; focus groups with students, parents and educators in local schools; workshops with educational and public policy organizations; webinars and key informant interviews. In total, 4002 individuals responded to the online survey and over 1100 people participated in interviews, webinars and focus groups. The full report on the consultation is available on People for Education’s website.

The surveys and the public engagement show strong overall support for clear goals for the education system in areas beyond literacy and numeracy, and for measuring progress towards goals in social-emotional skills, creativity and innovation, health, and citizenship alongside test scores in literacy and numeracy.

| Percentage of respondents who agree with expanded goals and measures | ||

| Areas | We should set goals | We should measure progress |

| Health | 88% | 75% |

| Citizenship | 84% | 71% |

| Creativity | 84% | 74% |

| Social-emotional skills | 89% | 79% |

| Quality learning environments | 96% | 89% |

Survey respondents indicated that current information about school success leaves many unanswered questions:

- While a majority still believe that they can “probably” tell if a school is doing a good job by its literacy and numeracy test scores, almost half (47%) would probably or definitely not assume that if a school has good literacy and numeracy scores it is doing a good job overall.

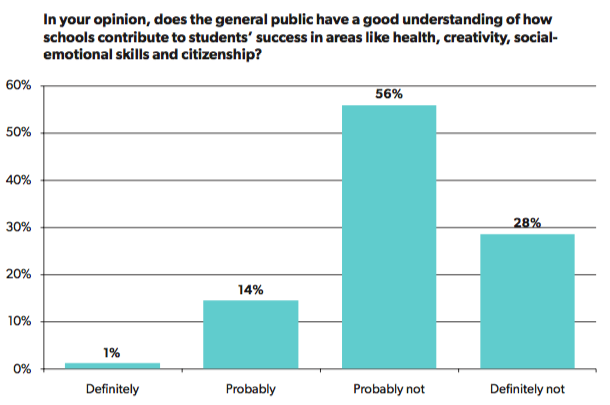

- The vast majority of respondents (84%) said the general public definitely or probably does not understand how schools contribute to students’ success in domains like social emotional skills, creativity, health and citizenship.

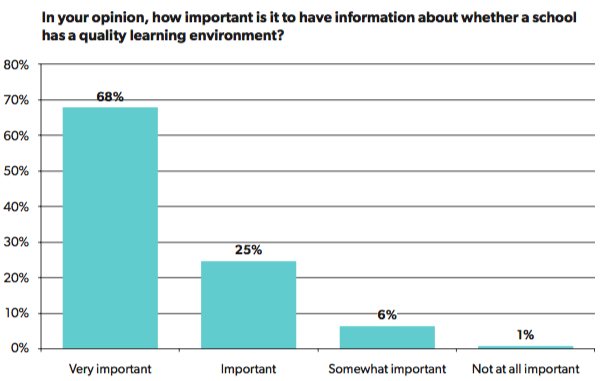

- Over two-thirds (68%) of survey respondents said it is very important to have information about the learning environment in a school. This might include the quality of school facilities, access to learning resources, relationships between and among students, staff and parents, and opportunities for all students to learn.

The convergence of need and capacity … gives us an opportunity to improve the life outcomes of our children and youth who make up 25% of our population and 100% of our future.

– Bruce Ferguson and Keith Power

Research conducted for People for Education by Bruce Ferguson (SickKids Hospital and the University of Toronto) and Keith Power (Memorial University), shows that school-based programs that promote physical and mental health are important from individual, social, and economic perspectives.

Their research also found that to be effective, “health programs must be intensive, long-lasting and involve a multi-pronged approach that includes teaching about health, changes to the school environment, and creating partnerships with the wider community.” Despite the evidence, according to the authors, these types of comprehensive school health programs are rarely implemented.

The benefits to students of school-based health programs include evidence of improved academic outcomes; the promise of reducing short and long-term distress caused by mental health issues, and reduced risk of chronic disease.

The benefits to society are both economic and social. Health care represents approximately 40% of all public spending, and nearly half of that is spent on treating chronic diseases. According to Ferguson and Power, chronic diseases can be prevented by teaching students to adopt healthy lifestyles from an early age. Education is also beneficial in terms of reducing mental illness. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for youth aged 10-24 years, and the majority of mental health disorders emerge during childhood and adolescence.

Ferguson and Power stressed that it is time to “move forward assertively to implement comprehensive health promotion programs in schools.” They said that it is critical that schools and school systems select health promotion initiatives that are evidence-based, and that they monitor implementation and outcomes of these programs. The availability of widely accepted, appropriate measures could promote a change in how programs are chosen, implemented and evaluated.

The measurement model they proposed for evaluating health would include measures of academic achievement and physical fitness and a number of student (and possibly parent) “self-report” tools that look at attitudes, lifestyles, risk behaviours, diet and activity levels. While there are limits in existing instruments to evaluate universal mental health and well-being in school settings, the authors point to tools to assess feelings of well-being, resilience, quality of relationships with peers and adults, management of day-to-day stressors, risk behaviours (including alcohol and substance use), and engagement in home, school and community.

In their report, they say “Effective school-based health measures target student health outcomes and the associated opportunities that they have had to learn, to access programs and participate in physical activity. They look at students’ social relationships, sense of self- well-being, confidence and resilience.”

We have seen a revolution – or perhaps evolution would be a more appropriate term – in educational thinking over the past twenty years…Instead of seeing reason and emotion as belonging to separate and independent faculties (the former controlling the latter), social, emotional and cognitive processes are all bound together in a seamless web.

– Stuart Shanker

Dr. Stuart Shanker, author of the Measuring What Matters paper on social-emotional learning, describes five core aspects of social-emotional functioning that research shows are critical for a child’s educational attainment and their long-term well-being and ability to contribute to society.

Shanker outlines five critical competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, interpersonal relations, and decision-making.

He argues that students can learn these social and emotional competencies just as they learn formal academic skills – through their regular interactions with peers, teachers, and school staff inside and outside of the classroom.

SELF-AWARENESS refers to a range of capacities including students’ ability to identify and understand emotions and feelings – in themselves and others – and their ability to have an accurate sense of their own capacity for success, their learning styles and the areas where they are more likely to struggle. Greater self-awareness is a predictor of higher levels of social and professional success, higher life satisfaction and even the likelihood that students will stay in school.

SELF-MANAGEMENT includes such skills as being able to set short- and long-term goals, plan, stay on task, manage stress and develop positive motivation and a sense of hope and optimism. This competency also includes strategies for dealing with things like anxiety, anger, and depression, and controlling impulses, aggression, and antisocial tendencies. Students can develop stronger self-management skills to calm themselves down when they’re stressed, and motivate themselves when they’re feeling listless or lethargic.

SOCIAL AWARENESS is the ability to take others’ perspectives into account and to empathize. This requires the capacity to understand and predict others’ feelings and reactions. Students with stronger social-awareness skills tend to be more academically competent. Well-developed social awareness is associated with reduced bullying, stronger prosocial tendencies, and enhanced emotion regulation. Poorly developed social awareness is associated with higher levels of aggression in adolescents.

INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP skills are connected to higher levels of self-esteem, happiness, and enjoyment of school. Relationship skills involve things like the ability to develop and maintain healthy friendships, deal with conflict, resist negative social pressures, seek help when necessary, and work well with others.

DECISION MAKING SKILLS involve developing a range of strategies to solve academic, personal, and social problems, and having both the capacity to base decisions on moral, personal, and ethical standards as well as the ability to recognize the importance of making responsible decisions. Shanker says there is strong evidence that responsible decision-making contributes to academic success.

Both individually and collectively, these social-emotional skills contribute to higher academic and long-term success and fewer problems at school, and in life and work. The importance of these skills is widely recognized, and has been increasingly heavily emphasized by employer and business groups as well as educators and neuroscientists.

Shanker says that it is vital that we begin to set goals for, and measure schools’ success in building, social and emotional skills. He provides an extensive list of effective tools for measuring students’ social and emotional strengths and for identifying the areas that need to be strengthened. He mentions the Early Development Instrument, used in early childhood to measure things like social competence and emotional maturity, and other measurement tools that assess emotional, social and behavioural skills in students, and as well as aspects of the learning environment such as classroom organization, teacher responsiveness and expectations for student achievement, and teacher collaboration and communication.

As important as the three Rs are, today’s students must develop the social and emotional capacities necessary for healthy and productive living. Schools play an important part in that developmental process, a process that must be assessed as seriously as any other dimension of learning. Measuring What Matters marks a major step forward in how we understand and meet students’ complex needs.

– Stuart Shanker

Creativity is an essential aspect of schooling and one of the key competencies that young people need for success in the modern world of ever-increasing change. Despite its importance, it is usually overlooked in measures of school quality and student outcomes.

– Rena Uptis

According to Queen’s professor, Rena Upitis, author of the creativity domain paper for Measuring What Matters, creativity and innovation skills allow students to learn more effectively in all academic disciplines and subjects.

Upitis – along with many other academics – defines creativity as the generation of novel and valuable ideas or products. She notes that researchers have described creativity as a process rather than an outcome: an idea that moves from preparation and incubation to illumination and verification. This process, according to Upitis, provides students with experiences “in which there is no known answer, there are multiple solutions, tension of ambiguity exists and imagination is as valued as rote knowledge.”

Upitis describes critical thinking as a “sister skill” to creativity. She says that being creative or innovative requires the skills to assess both the process and the products of the creative act. Critical thinking involves a process of conceptualizing, seeking accuracy and clarity, resisting impulsive solutions, being responsive to feedback, planning and being aware of one’s own thinking.

According to Upitis, creativity and innovation can be fostered and reinforced across the entire curriculum as well as through extra-curricular activities. She says, “When students gain new insights about solving a math problem or when they produce genuinely interesting projects, they are manifesting their creativity.”

Schools help students develop their creativity in a number of different ways: through everyday teaching strategies, including things like encouraging students to pose questions and share insights, providing opportunities for discussion and debate and helping students identify problems; by teaching creativity directly; and through programs that provide rich opportunities for creativity.

It is both possible and desirable to measure creativity in schools. A number of different researchers have described creative competencies as including:

- Fluency, flexibility, originality, and the ability to elaborate;

- Metaphorical thinking

- Skilled observation, visualization, pattern detection, empathy, and play;

- Tolerance for uncertainty, open-mindedness, risk taking, patience, deferral of judgment, and resilience;

- The ability to pose problems, gather information through all the senses, find humour, think interdependently, communicate with precision, strive for accuracy, think flexibly, and respond with wonderment and awe;

- Reframing, detecting, and decentering.

Academics at the University of Winchester in England have developed a comprehensive assessment model that incorporates the competencies of both creativity and critical thinking. The assessment tool provides a way to assess creative thinking that can be used by teachers and by students to assess their own creative habits. The competencies were divided into five “habits”:

INQUISITIVE (wondering and questioning, exploring and investigating, challenging assumptions)

PERSISTENT (sticking with difficulty, daring to be different, tolerating uncertainty)

IMAGINATIVE (playing with possibilities, making connections, using intuition)

COLLABORATIVE (sharing the product, giving and sharing feedback, cooperating appropriately)

DISCIPLINED (developing techniques, reflecting critically, crafting and improving)

Measuring the conditions for creativity within school is an important aspect of measuring creativity. Here, the emphasis is not on the “outputs”—that is, the creative products created by individual students, but rather, on the “inputs”— namely, the situations in which students might be called upon to think and act creatively. Examples of creative inputs would include scientific investigations, entrepreneurial projects, theatre and dance performances, independent research opportunities, debating clubs, school-community partnerships, fine and performing arts classes, and integrated curricula.

One of the main advantages of evaluating creativity in schools is that it underscores the importance of creativity to the school experience. Measuring creativity also provides critical feedback, guiding students in their creative development and guiding schools toward optimal conditions for fostering creativity. For all of these reasons, creativity must be included in measures of student and school success.

– Rena Upitits

Low levels of voter turnout, indifference about difficult choices the society faces, intolerance, and political extremism are considered evidence that societies have failed to equip the young with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that citizenship requires.

– Alan Sears

Alan Sears, professor at the University of New Brunswick, says that citizenship education is considered a key component of education in most democratic countries, but that the reality does not match the ideal. He says that a study of 24 countries by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement showed that the “rhetorical commitment to informed and engaged citizenship as a central educational outcome has rarely been matched by a concomitant allocation of resources or actual curricular priority.”

In his paper for Measuring What Matters, Sears defines citizenship education as the acquisition of a core set of civic knowledge, skills, and values, including knowledge of historical and political facts and a nuanced understanding of social issues. According to Sears, “Through citizenship education students develop skills to engage with the formal political system and civil society organizations; and establish the values and attitudes of democratic citizenship.”

Sears says that a democratic and socially cohesive society relies on people understanding the impact of their behaviour and decisions on others and playing an informed role in the affairs of a democratic society.

In school, students learn citizenship skills in a range of ways:

- learning historical and political facts,

- learning to distinguish between facts and values, and knowing the standards that apply in evaluating each

- developing capacities for articulate communication

- recognizing and valuing different perspectives,

- understanding the impact of their behaviour and decisions on others

- distinguishing between a person and the argument the person in making,

- avoiding bias and distortion in the presentation of one’s own argument.

- being encouraged by teachers and school leaders to have a voice and be actively engaged in their schools and communities

Student voice is a particularly important aspect of citizenship learning. Sears cites forty years of international research that “conclusively demonstrates students’ belief that they are ‘encouraged to speak openly in class’ is a ‘powerful predictor of their knowledge of and support for democratic values, and their participation in political discussion inside and outside school.’”

According to Sears, little is known about the civic knowledge, skills and values of Canadian students or about citizenship education practices in Canadian schools. In contrast, in the United States, civics is part of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and in Australia, the National Assessment Program includes civics and citizenship. Both assessments also include surveys for schools, teachers, and students about how citizenship is addressed in curricular, co-curricular, and extracurricular activities. Sears also says that, unlike other jurisdictions, teachers in Canada are being provided with almost none of the structural supports necessary to successfully deliver strong citizenship education.

Measuring success in citizenship education could include assessing students’ knowledge of key concepts and their ability to apply them, as well as the recall of basic facts; assessing students’ actual and potential engagement; measuring students’ opportunities to participate in school or community activities, and their access to programs that require them to use core citizenship skills.

If we are serious about Canadians taking a full and active part in the affairs of their society, fulfilling their obligations as productive and contributing members of society, defending their rights and according those rights to others, they must understand the laws and institutions that govern them and the rights to which they are entitled. Taking citizenship education seriously also requires thoughtful assessment.

– Alan Sears

Student and school success cannot be defined solely by the measurement of student performance in literacy and numeracy, the accumulation of subject credits, or graduation rates. Schools are complex, dynamic systems that influence students’ academic, affective, social, and behavioral learning.

– Nina Bascia

Professor Nina Bascia, from the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, says in her Measuring What Matters paper, that it is vital that we understand the complex and interactive nature of schools, and not assume we can measure the quality of students’ learning environments with simple checklists.

For many decades, researchers and educational practitioners have examined the school environment as a basis for learning, and worked to understand how to develop school settings that positively influence student learning. While not denying the impact of students’ socio-economic status or the other factors that students “brought with them” to school, research has shown that school practices and organizational structures can be altered by educators to make a positive difference in student learning.

Bascia’s paper says that it is important to look at the range of “contexts” that exist within and around the school and that it is the interaction between all of the factors that has an impact on the overall quality of the learning environment. Research warns against using “discrete school characteristics” to measure success, and supports an approach that looks at schools as dynamic systems that influence a broad range of dimensions of student learning. In this “school context” model, the three main groups in the school – leaders (both administrators and teachers who “lead for learning”), teachers and students work in interrelated subsystems.

According to Bascia and other researchers, teaching and learning happens in classrooms which are “nested” within teacher communities, which are nested within schools, which are nested within the wider community. As a result, what occurs beyond the classroom influences (and is influenced by) what occurs within the classroom.

All of the Measuring What Matters papers show that the quality of the school itself is a core component of success in each domain. The papers make it clear that student success arises through a broad array of skills, experiences, opportunities and outcomes across a number of domains, from social-emotional learning and health, to creative, critical thinking and qualities of democratic citizenship. Shanker, Sears, Upitis and Ferguson all point to the whole school environment and its impact on things like students’ opportunities to participate in creative endeavours, its effect on their social-emotional skills and health, and its provision of opportunities to participate as engaged citizens in the school. And they agree that it is not enough to simply measure outcomes in a few subjects, or graduation rates.

It is possible to measure the quality of learning environments, but it is not simple.

Information can be collected through focus groups, observational methods, interviews, town hall discussions, and surveys. Measurement methods should include students, teachers, staff and parents, and should assess the full range of factors that shape student and educator experiences of the learning environment. Data on learning environments can inform individual schools about the areas where they excel and the areas that require improvement. Such data can also be informative at the system level, helping decision-makers to determine the effects of policies and reform efforts.

The whole school environment, including its individuals and their relationships, the physical and social environment and ethos, community connections and partnerships, and policies, are seen as important areas for action if a school is to promote health.

– Dr. Bruce Ferguson

Measuring is useful, to really know what your kid is doing in school. If the school isn’t doing well, it is not really good to be in that environment.

– Grade 4 student, focus group

Many participants in surveys, focus groups, and workshops underlined the importance of measurements that are focused on schools and the education system – not just students’ outcomes.

While participants agreed that we should be measuring outcomes in broader areas, they cautioned that we must also measure inputs, i.e. what are the opportunities students have to learn, to access programs, to participate etc.?

The enthusiasm we have experienced in discussions about this project has been tempered by many questions and some concerns. This reflects a recognition of the possible impacts of an initiative like this – participants want to ensure that Measuring What Matters has carefully worked through the potential pitfalls or unintended consequences of the project.

Key concerns and questions included:

- How can we develop measures for success in areas – like health and citizenship – that are a shared responsibility of families, schools and broader services for children and youth?

- How can we ensure that measurement doesn’t become an end in itself, or just another add-on to schools’ already full workloads?

- It is vital that as we add broader goals and measures, we also add the “time and space” into the system to support the work that needs to be done to meet the goals.

- Measurement, when it is done badly, or when it measures only quantitative outcomes, always runs the risk of leading to simplistic and negative school rankings. How will this initiative avoid that?

- Will it be possible to do this without creating stigma for schools or students that aren’t doing so well?

- How can we ensure the goals and measures we set recognize the importance of, and promote equity between schools, and between students within schools?

- It’s going to be very important to find ways to measure these new areas that are valid and reliable as well as practical to administer and useful for educators and families.

Two important outcomes have emerged from the first phase of Measuring What Matters;

- Our existing measures in literacy and numeracy are critical.

- Student success is much broader than the narrowly defined indicators that we currently use. Knowledge, skills, dispositions and habits in such areas as creative, critical problem solving, interpersonal relationships, civic engagement, self-confidence and health literacy, amongst others, are as important as literacy and numeracy in defining student success.

Both the experts and the public agree that education plays a critical role in ensuring we have a democratically cohesive society, which is both economically and socially productive. But in order for education to realize its potential in helping build the society of the future, the public and the experts also agree that it is not enough to expect that vital social-emotional, creativity and innovation, citizenship or health skills will emerge organically as a by-product of good schooling focused on one or two important subjects.

The papers present a wide range of evidence that suggests the qualities and opportunities of the learning within schools can enhance or constrain students’ abilities to develop vital skills beyond literacy and numeracy. They make the case these skills and habits in areas like creativity or social emotional learning are of equal importance for student success. In fact, they may be key pathways to student success in a range of subject disciplines.

Stuart Shanker, the domain lead on social emotional learning, for example discusses a current ‘revolution or evolution’ in the ways we understand social, emotional and cognitive processes—that reason and emotion are not separate from each other but bound together in a ‘seamless web’. Bruce Ferguson details how physical and mental health are ‘inextricably linked’. Alan Sears argues that explicit development of democratic citizenship knowledge, skills and dispositions requires a complementary effort in schools to promote student voice and active engagement in school decision making.

Each domain is complementary to the other. They work as an interactive suite of characteristics that enhance or constrain each other, not as discrete subject/ skills for students. When Rena Upitis argues for qualities of experimentation and risk within creativity, she is also touching on Stuart Shanker’s points about student self-confidence as well as students’ ability to develop resilience within social emotional learning. The knowledge, skills and habits that underpin each domain could also be thought of as a seamless web. The characteristics of quality learning environments that Nina Bascia describes also provide opportunities for students to express themselves creatively, engage in the community, take risks, participate in school decisions and establish rich learning relationships with their peers and the adult educators in the school.

Across the consultation and within the papers, there is an explicit articulation that schools are not solely responsible for this work. Each domain paper places an emphasis on the need for schools to be open and share responsibility for student learning beyond the school walls. The papers highlight the importance of community partnerships and linked public infrastructure to allow students to contribute and establish learning relationships outside the school, and to access recreational opportunities or additional supports. They bring a collective orientation to supporting students within these critical areas of student success. Most importantly, they are hopeful and optimistic. They detail the rich learning that is occurring in schools today, which could be even more profound tomorrow.

Through the extensive feedback we received about the domains, we have come to see even more clearly that there are major interconnections between all of them. These areas of overlap are useful in terms of helping build a group of measures that work as a set, and – recognizing the diversity of students in our schools – that offer different pathways to rich experiences and learning.

We have also received stern warnings of possible dangers – adding to teacher overload, feeding an unhealthy process of comparing schools, building expectations without resources. We got many recommendations about ways to proceed through the challenging waters – look at growth, progress and change over time; see how measures can be used to leverage stronger partnerships; maintain a focus on equity and the most vulnerable students.

We have been left with strong support for the project, and a new set of questions for the next round. Starting in November 2014, our academic experts will begin looking at how the domains fit into a range of Ontario curriculum and the public consultations will continue online.

For more information, go t0 the Measuring What Matters page

Bascia, N. (2014). The School Context Model: How School Environments Shape Students’ Opportunities to Learn. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Ferguson, B. and Power, K. (2014). Broader Measures of Success: Physical and Mental Health in Schools. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Gallagher, K. (2014). Measuring what matters – Report on public engagement in a broader measure of success. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Sears, A. (2014). Measuring What Matters: Citizenship Domain. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Shanker, S. (2014). Broader Measures for Success: Social/Emotional Learning. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Upitis, R (2014). Creativity; The State of the Domain. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

The Measuring What Matters reports and papers were developed in partnership with lead authors of each domain paper. Permission to photocopy or otherwise reproduce copyrighted material published in this paper should be submitted to People for Education at [email protected].

Document Citation

This report should be cited in the following manner:

People for Education (2014). Measuring What Matters: Beyond the 3 “R’s”. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014

We are immensely grateful for the support of all our partners and supporters, who make this work possible.

Annie Kidder, Executive Director, People for Education

David Cameron, Research Director, People for Education

Charles Ungerleider, Professor Emeritus, Educational Studies, The University of British Columbia and Director of Research, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Lindy Amato, Director, Professional A airs, Ontario Teachers’ Federation

Nina Bascia, Professor and Director, Collaborative Educational Policy Program, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Ruth Baumann, Partner, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Kathy Bickmore, Professor, Curriculum, Teaching and Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Michelle Boucher, University of Ottawa, Advisors in French-language education and Ron Canuel, President & CEO, Canadian Education Association

Ruth Childs, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Jean Clinton, Associate Clinical Professor, McMaster University, Dept of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences

Gerry Connelly, Director, Policy and Knowledge Mobilization, The Learning Partnership

J.C. Couture, Associate Coordinator, Research, Alberta Teachers’ Association

Fiona Deller, Executive Director, Policy and Partnerships, Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario

Kadriye Ercikan, Professor, Measurement, Evaluation and Research Methodology, University of British Columbia

Bruce Ferguson, Professor of Psychiatry, Psychology, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto; Community Health Systems Research Group, SickKids

Joseph Flessa, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Joan M. Green, O.Ont., Founding Chief Executive O cer of EQAO, International Education Consultant

Andy Hargreaves, Thomas More Brennan Chair, Lynch School of Education, Boston College Eunice

Eunhee Jang, Associate Professor, Department of Applied Psychology & Human Development, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Christopher Kotz, Senior Policy Advisor, Ontario Ministry of Education

Ann Lieberman, Stanford Centre for Opportunity Policy in Education, Professor Emeritus, Teachers College, Columbia University

John Malloy, Director of Education, Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board

Roger Martin, Premier’s Chair on Competitiveness and Productivity, Director of the Martin Prosperity Institute, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Ayasha Mayr Handel, Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services

Catherine McCullough, former Director of Education, Sudbury Catholic District School Board

Robert Ock, Healthy Active Living Unit, Health Promotion Implementation Branch, Health Promotion Division, Ontario Ministry of Health

Charles Pascal, Professor, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Jennifer Riel, Associate Director, Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Joanne Robinson, Director of Professional Learning, Education Leadership Canada, Ontario Principals’ Council

Bruce Rodrigues, Chief Executive Officer, Ontario Education Quality and Accountability Office

Pasi Sahlberg, Director General, Centre for International Mobility and Cooperation, Finland

Alan Sears, Professor of social studies and citizenship education, University of New Brunswick

Stuart Shanker, Research Professor, Philosophy and Psychology, York University; Director, Milton and Ethel Harris Research Initiative, York University; Canadian Self-Regulation Initiative

Michel St. Germain, University of Ottawa, Advisors in French-language education

Kate Tilleczek, Professor and Canada Research Chair, Director, Young Lives Research, University of Prince Edward Island

Rena Upitis, Professor of Education, Queen’s University

Sue Winton, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Education, York University and former Early Learning Advisor to the Premier Deputy Minister of Education