New report by People for Education shows gaps and inconsistencies in implementation of anti-racism and equity strategies across Canada, and particularly in publicly funded schools across Ontario.

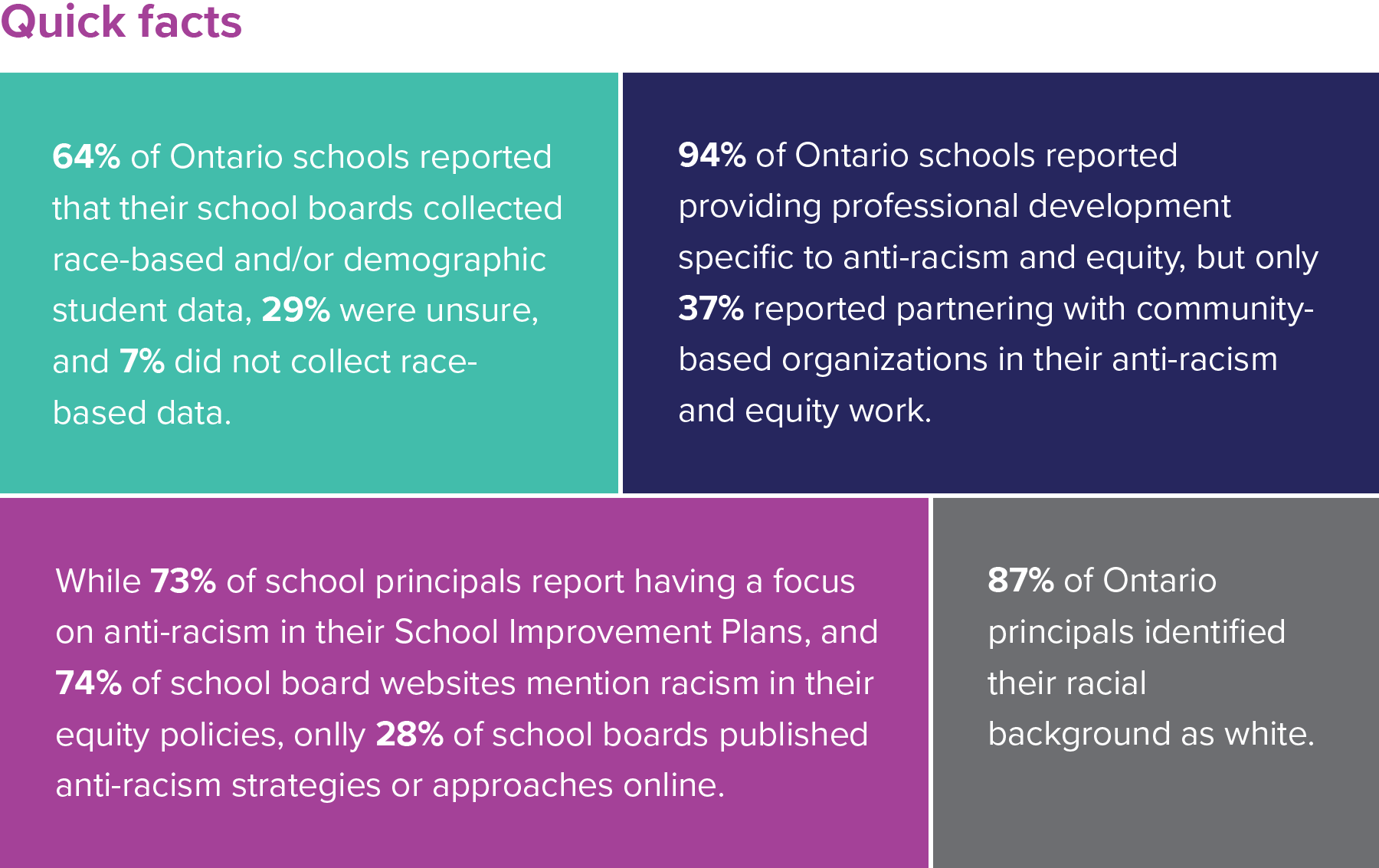

Anti-racism policies are gradually becoming more widespread in Canada. In 2019, the Government of Canada launched a 3-year plan for long-term action towards increasing equitable access to and participation in the economic, cultural, social, and political spheres.1 At the jurisdictional level, Ontario was the first province to pass an anti-racism act in 2017, and most recently in 2022, British Columbia and Nova Scotia passed landmark legislation on anti-racism policies across their provincial public institutions.2

But what does anti-racism mean? And why are these policies happening now?

Anti-racism is the belief in equality among all races, and that racial inequality is an outcome of problematic policies and power imbalances.3

Anti-racism has emerged as a priority focus area in Canada because of a long history of racial discrimination, underscored by numerous current events triggering discussions on race, inequity, and social injustice. In particular, the public education system has faced the challenge of addressing incidents of racism in their schools, as well as ongoing efforts to ensure that every child can access their human right to a quality education.

While anti-racism policies have emerged from publicly funded school boards across Ontario in recent years, new research from People for Education (PFE) reveals significant inconsistencies in the execution of these strategies. This report explores findings from an online scan completed during summer 2022 of the websites of 72 publicly funded school boards in Ontario, in addition to data collected in the 2021-22 Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS).

The goal of this progress report on anti-racism policy across Canada, and specifically in publicly funded school boards in Ontario, is to share evidence about the work that has been accomplished to date and provide three key recommendations on how to move forward in advancing anti-racism.

The past year has been filled with multiple events that have triggered discussions on discrimination and signalled calls for equity. In Canada, discoveries of mass unmarked graves at residential school sites have forced governments and institutions across the country to take a closer look at their discriminatory practices and the role that they play in perpetuating systemic racism.4 At the same time, the Black Lives Matter movement continues to grow, fuelled by stories of police brutality and disproportionate enforcement actions against Black, Indigenous, and racialized individuals.5,6 In the domain of public education, school boards are receiving complaints about anti-Black racism, as was the case in Ontario’s Peel District School Board, where an internal review revealed the far-reaching impacts of racism on Black students: high rates of receiving disciplinary measures, high rates of being streamed into low academic pathways, lack of representation in the curriculum and school community, as well as a significant lack of community engagement.7

These are just some of many examples that illustrate the need for increasing public understandings about anti-racism and anti-racist policy development. This direction is a marked shift from focusing on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) to explicitly naming the role that race—and as it follows, racism—has had in shaping our society.

The racial inequality that exists in the world is rooted in policies, power, and systems. The role of anti-racist policy is essential to address this inequality in three ways:

- Naming race and racism as driving factors in the outcomes of different racial groups;

- Recognizing how racism is embedded in the systems, institutions, and structures where we exist; and

- Understanding that different treatment is necessary for equal outcomes.

Key Terms

ANTI-RACISM: Belief in equality among all races, and that racial inequality is an outcome of problematic policies and power imbalances.8

EQUALITY: Sameness or equivalence in number, quantity, measure, or treatment.9

EQUITY: Fairness and justice in processes and in results, which often requires differential treatment and resource redistribution to achieve a level playing field among all individuals and communities.10

DIVERSITY: A range of different social identities and backgrounds (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, ability, immigration status, etc.).11

INCLUSION: The act or practice of including and accommodating people who have historically been excluded.12

RACISM: The belief that different races possess distinct and inherent characteristics, abilities, or qualities, so as to distinguish them as inferior or superior to one another.13

In Canada, 6 of 13 jurisdictional governments have developed policy initiatives to tackle systemic racism and discrimination. This work ranges from developing strategies and action plans, forming advisory councils or committees, to passing new legislation.

Recent non-legislative steps include the creation of Ontario’s Anti-Racism Strategic Plan, Nova Scotia’s Office of Equity and Anti-Racism Initiatives, Alberta’s Anti-Racism Action Plan, the Ministerial Committee on Anti-Racism in Newfoundland and Labrador, and the appointment of a commissioner on systemic racism in New Brunswick.14 However, as these initiatives are not legislated, their ability to influence systems change has been questioned by critics who argue that they do not effectively hold individuals and institutions accountable.15

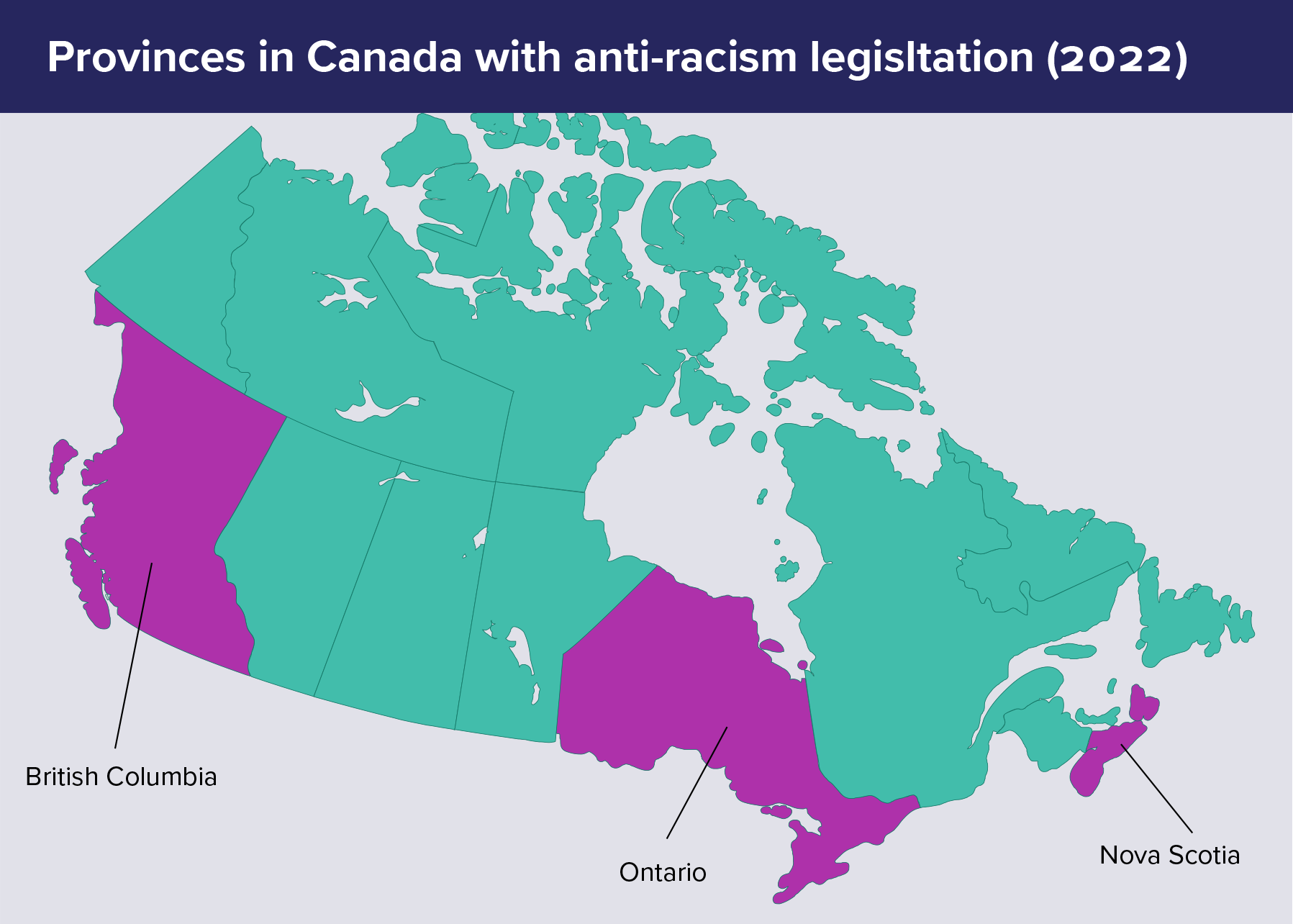

On the other hand, three provinces have taken legislative steps to advance anti-racism. In May 2022, British Columbia introduced the Anti-Racism Data Act that was co-developed with Indigenous Peoples.16 The new legislation focuses on key areas such as a continued collaboration with Indigenous Peoples, the creation of a provincial anti-racism data committee to collaborate with government on how data is collected and used, increasing transparency and accountability, requiring government to release data on an annual basis, and periodically reviewing the act.17

In April 2022, Nova Scotia passed the Dismantling Racism and Hate Act, committing the Government of Nova Scotia to the development of a provincial strategy and a health equity framework by July 2023, including the creation of data standards to monitor and address systemic hate, inequity, and racism.18 The Act was developed by an all-party committee following extensive consultations with community members. The Minister responsible for the Office of Equity and Anti-Racism Initiatives will be required to submit an annual progress report on these activities.19

Table 1: Overview of legislation on anti-racism in British Columbia, Nova Scotia, and Ontario

In Ontario, recommendations to combat racism and discrimination date back as far as 1992 with the Stephen Lewis report on race relations in Ontario.20 This document provided landmark recommendations to combat systemic racism in Ontario. However, it wasn’t until 2017 that the Ontario government introduced the Anti-Racism Act, which sets out requirements to maintain an anti-racism strategy and establish targets and indicators to measure the effectiveness of the strategy.21 Specific to education, in 2017, Ontario also released a three-year Education Equity Action Plan that commits to developing a consistent process for collecting, analyzing, and publicly reporting on disaggregated identity-based data.22

In April 2022, the Alberta Anti-Racism Advisory Council presented an Anti-Racism Act for approval, which required public bodies to collect race-based data, carry out impact assessments, and report on progress. However, the bill was not passed by the Alberta government.23

While some provincial governments have taken legislative action to address anti-racism, the outcomes are yet to be seen. In the coming years, it will be crucial to monitor how community consultation, implementation, and accountability measures play a role in how these legislative policies come to fruition, and furthermore, their implications at the school board level.

Spotlight: Manitoba’s Creating Racism-Free Schools through Critical/Courageous Conversations on Race

In 2017, Manitoba Education and Training published a resource titled, Creating Racism-Free Schools through Critical/Courageous Conversations on Race.24 This document was created to encourage school communities (i.e., school divisions, schools, teachers, students, and families) to engage in conversations about racism. This 80-page resource includes background information on racism, human rights, FMNI peoples, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Additionally, there are conversation tools such as a question guide, a list of school indicators of inclusiveness with respect to FMNI students, and a self-reflection questionnaire.

In fall 2021, the Ontario Ministry of Education released the Board Improvement and Equity Plan (BIEP), which is a planning tool to support boards in advancing equity. By September 2022, all Ontario school boards were expected to be in the process of collecting voluntary student demographic data.25 A scan of school boards’ websites, and responses to PFE’s 2021-22 AOSS, show there is significant variability in how Ontario schools and school boards are approaching anti-racism and equity.

This scan involved a search of all 72 school board websites for information on whether they conducted a student census (e.g., student demographic data, identity-based data collection), school climate survey (e.g., well-being survey), staff census (e.g., workforce census), and parent survey. If a school board website provided information on a past and/or upcoming survey, they were included in the tally of participating school boards. The scan also included a search for an anti-racism strategy and/or the inclusion of anti-racism in equity policies on school board websites. The number of school boards that conducted each of these activities were tallied at the end of the scan for a final count. Limitations to this scan include missing information due to broken or missing links as well as outdated website content.

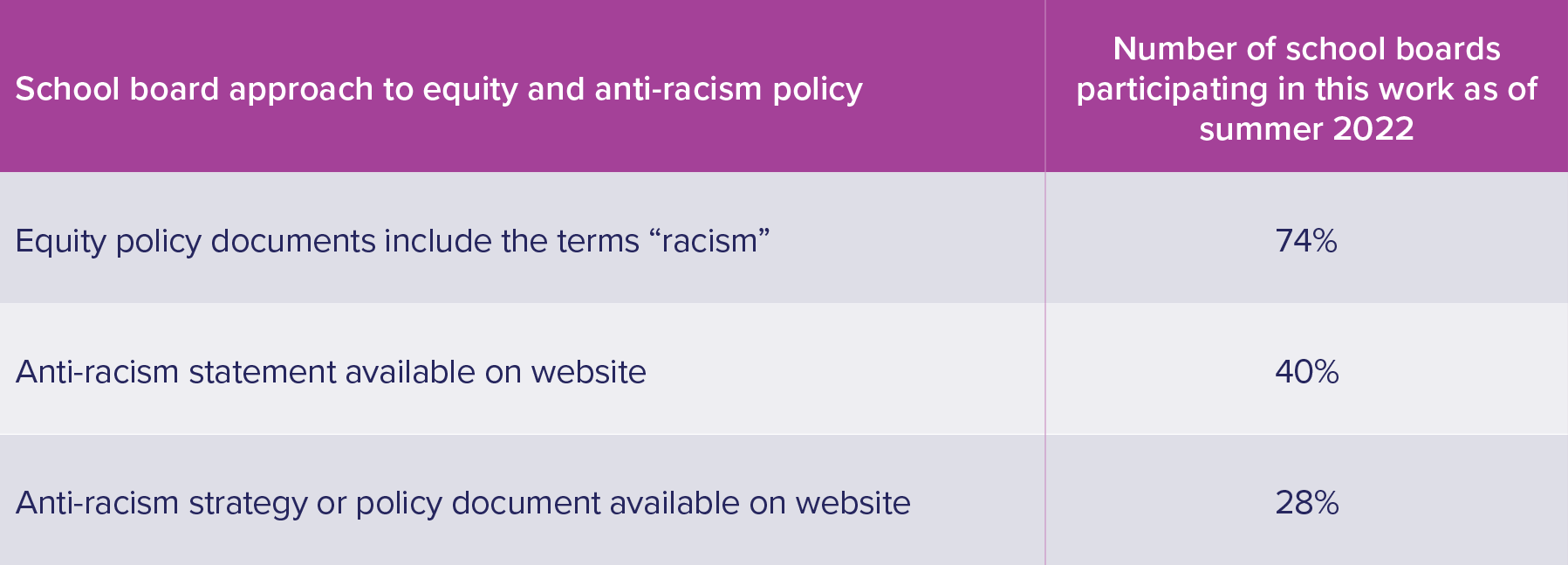

Overall, 74% of school board websites mentioned racism in their equity and inclusion policies, 40% of publicly funded schools had an anti-racism statement on their website, and 28% had an anti-racism strategy or approach available online.

Table 2: School board approaches to equity and anti-racism policy

Source: People for Education’s scan of websites of publicly funded school boards in Ontario, summer 2022

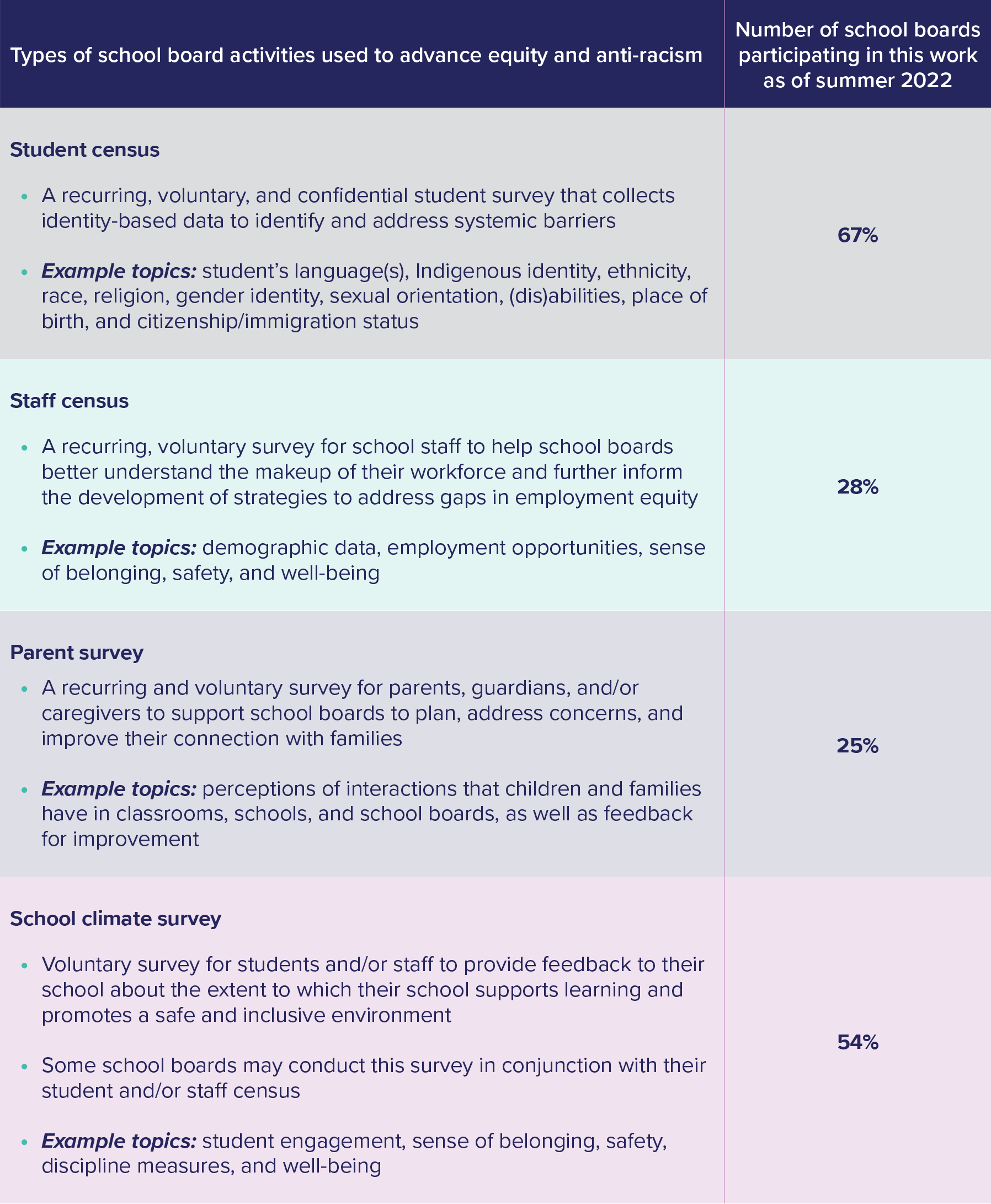

In Ontario, 67% of school boards have conducted or are in the process of conducting a student census and 54% have conducted a school climate survey; 28% of school boards have conducted a staff census. If school boards conducted two or more of these types of activities together (e.g., School Board A’s student census also asks questions about school climate), they were included in the total number of participants in each separate activity (i.e., School Board A is part of the total number of boards that conducted a student census in addition to a school climate survey).

Table 3: Overview of school board equity and anti-racism activities in Ontario

Source: People for Education’s scan of websites of publicly funded school boards in Ontario, summer 2022

These activities are an integral step in advancing equity and anti-racism because collecting data on individual experiences in the school community that can be sorted by demographic variables such as race yields valuable insights about how different groups experience systems as well as their various outcomes.

With different school boards taking these different approaches, how are individual schools implementing anti-racism and equity strategies set by their school boards? The PFE 2021-22 AOSS provides some insight into school-level implementation of policies and practices set by boards as well as the provincial government.

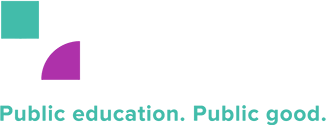

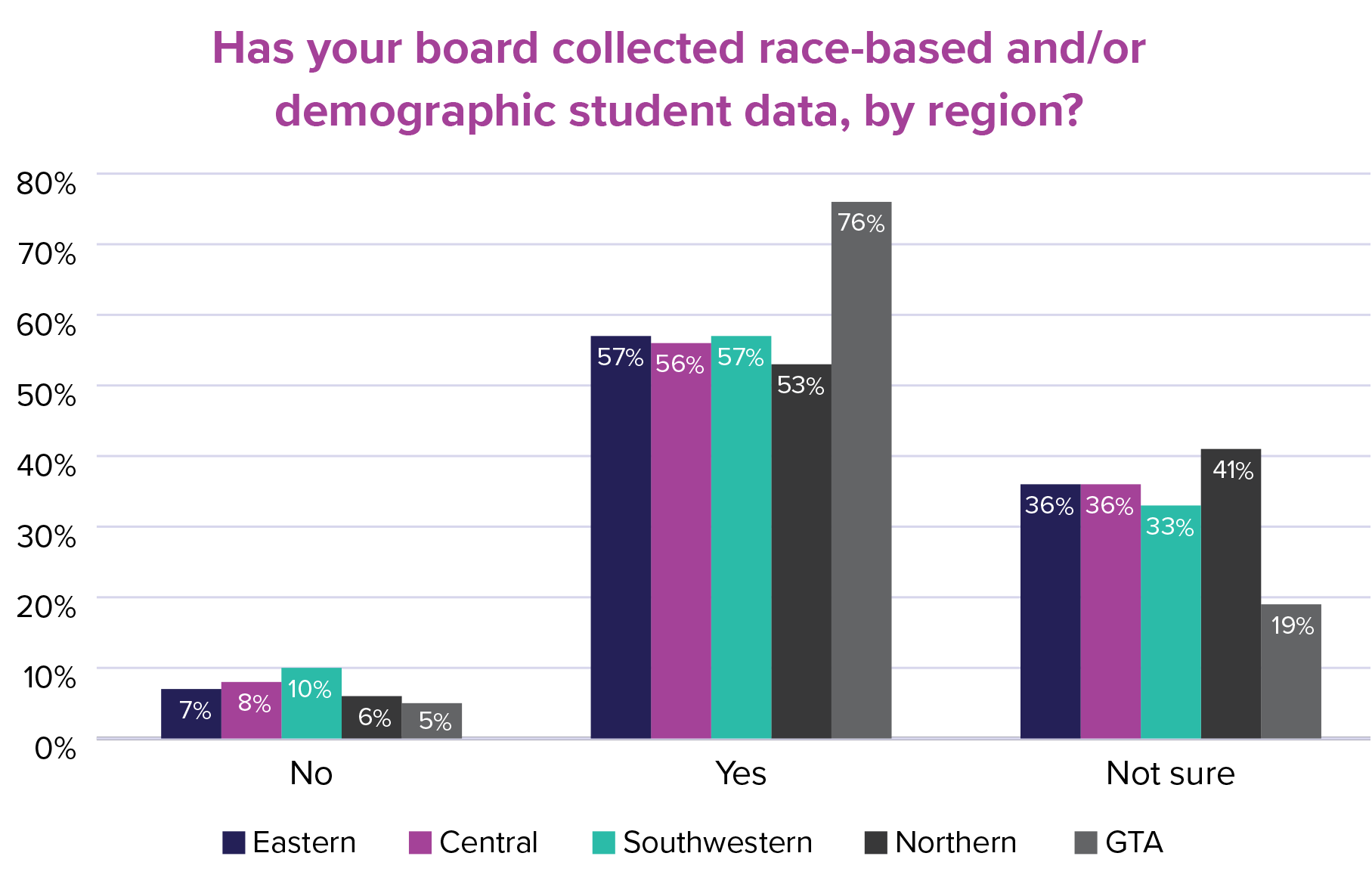

In the 2021-22 AOSS, 64% of Ontario school principals reported that their school boards collected race-based and/or demographic student data, 29% were unsure, and 7% did not collect race-based data. The GTA had the highest proportion of schools that reported collecting race-based data (76%) in 2021-2022, but in all other regions, this proportion was less than 60% (i.e., Northern: 53%, Southwestern: 57%, Central: 56%, Eastern: 57%).

Figure 1: Ontario schools collecting race-based and/or demographic student data, 2021-2022

Source: People for Education’s 2021-22 Annual Ontario School Survey

The significant proportion of principals who reported being unsure raises questions about how effectively the Ontario government and school boards are communicating with local school staff. When asked about the purpose of this demographic data collection, one secondary school principal from Southwestern Ontario wrote, “Not sure as to the specifics of work completed at central office as communication from the site is limited. There may be work being done but school might not be informed of the purpose of this work.” Understanding the rationale behind new initiatives requires clear communication, time, and resources. However, these are some of the things that were often cited by principals as being in shortage.

“Staff feel there is never enough time and resources for authentic learning and implementation,” expressed one elementary school principal from Central Ontario. Furthermore, another elementary school principal from the same region expressed that, “There is no time to offer meaningful PD. There are no occasional teachers to release staff and we cannot put classes together because of cohorting [connected to COVID].” These experiences highlight the administrative reality of implementing change; while fostering an understanding of the issue is necessary, it isn’t possible without the logistics.

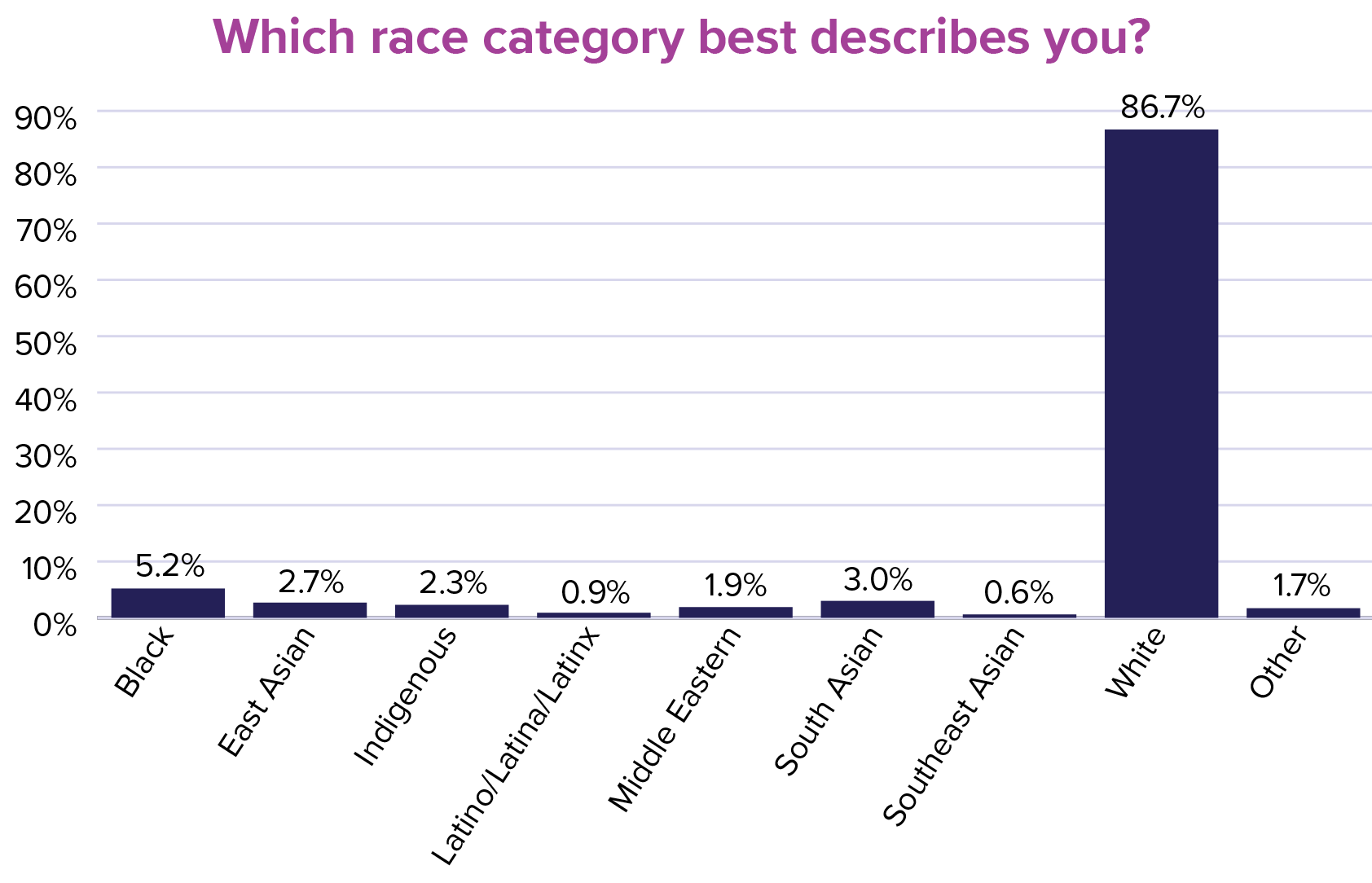

In an effort to support identity-based data collection and reporting, the 2021-22 AOSS was the first time that principals were asked to self-identify their racial background as an optional question. The vast majority of Ontario principals identified as white (86.7%), followed by Black (5.2%), South Asian (3.0%), East Asian (2.7%), Indigenous (2.3%), Middle Eastern (1.9%), other (1.7%), Latino/Latina/Latinx (0.9%), and Southeast Asian (0.6%).

Figure 2: Self-reported racial background of Ontario principals, 2021-2022

Source: People for Education’s 2021-22 Annual Ontario School Survey

This homogenous racial profile of school principals is a contrast to Ontario’s population, which is comprised of more than half of Canadian’s “visible minority” population.26 Race-based data collection, such as the above, provides foundational evidence to raise questions about disproportionate outcomes, examine the circumstances that may have contributed to these results, reflect what potential changes may be desired, and plan for improvement.

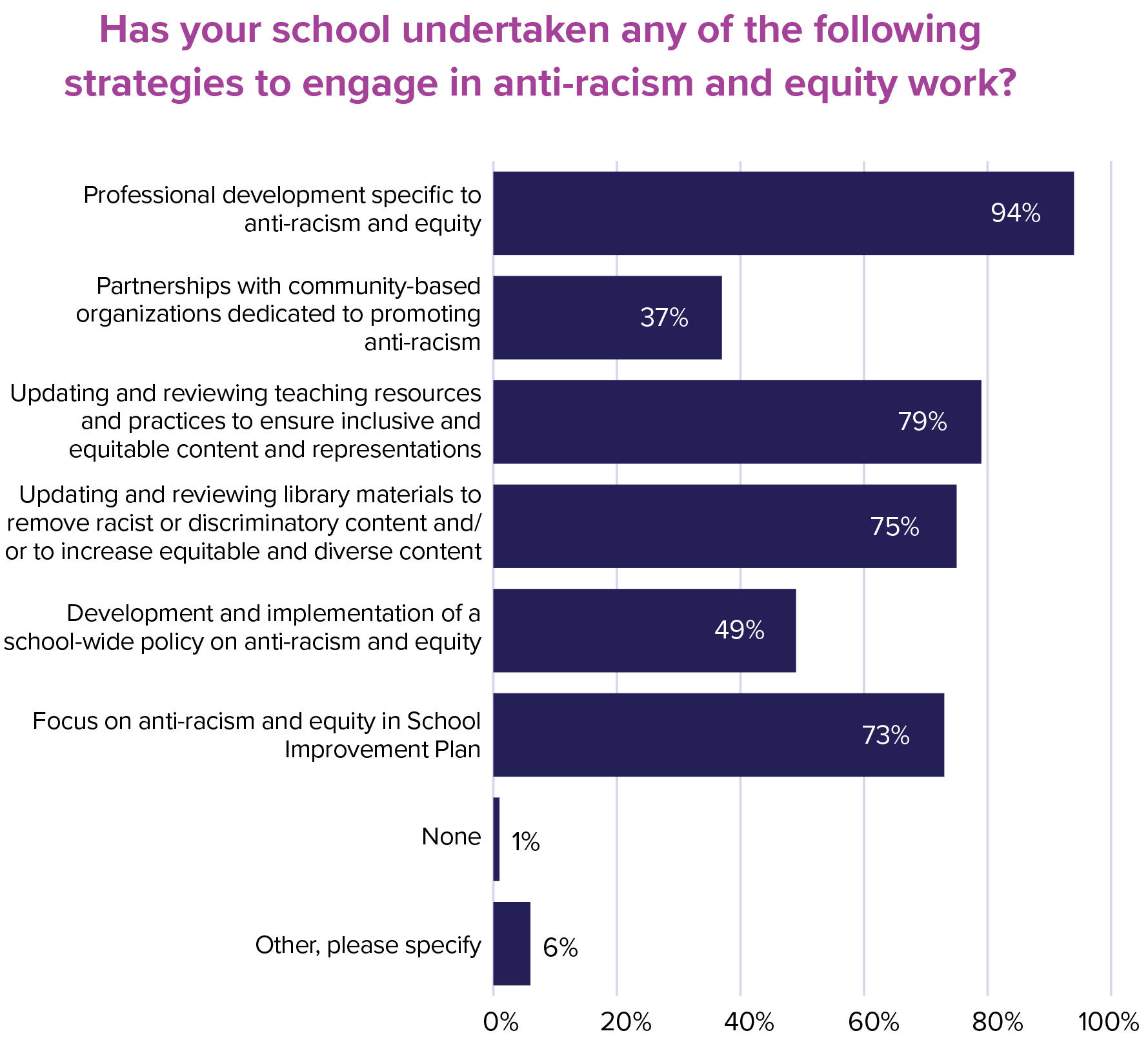

Principals were also asked to indicate all the strategies that their schools had undertaken to engage in anti-racism and equity work. Almost all Ontario schools (94%) reported providing professional development specific to anti-racism and equity, and most of them (79%) reported updating and reviewing teaching resources and practices to ensure inclusive and equitable content and representation.

Partnering with community-based organizations in their anti-racism and equity work, however, was the least commonly undertaken strategy (37%). This finding is concerning given that research has shown that students benefit when there are strong partnerships between schools, communities, and families.27 Furthermore, some principals reported a lack of support when pursuing this approach. One elementary school principal from Central Ontario explained, “We have asked about partnerships with community-based organizations promoting anti-racism but have not received communication back from our central lead at the school board.” These community-based relationships affirm student identities, increase sense of belonging, allow groups to learn from one another, encourage safe school environments, encourage community service, and improve student academic achievement.28

Figure 3: Types of anti-racism and equity strategies used by Ontario schools, 2021-2022

Source: People for Education’s 2021-22 Annual Ontario School Survey

There are several challenges in implementing anti-racism strategies in Ontario’s publicly funded schools. While some principals mentioned that having a dedicated staff member focused on anti-racism was helpful, others explained why this approach was not enough. An elementary school principal from Central Ontario wrote, “It can’t be 1 or 2 people leading the charge and everyone else is indifferent.” The integral role of staff buy-in was underscored, but part of what makes anti-racism work complex is that it requires reflection at an individual level.29

Another elementary school principal in Central Ontario elaborated, “Becoming anti-racist requires individual work to recognize and challenge your own bias.” Facilitating this type of reflection requires trust building and safe environments that allow teachers to be vulnerable. After all, embracing vulnerability “allow[s] ourselves to sit with other people’s pain and struggle as well as our own. We learn to tolerate our mistakes and failures rather than anesthetize ourselves to them.”30 The creation of this safe environment is challenging and complex, but necessary even in schools where the student population is predominantly white, which was another theme that was apparent among Ontario schools. One secondary school principal from Eastern Ontario explained, “… [w]e are a school whose vast majority of staff and students are white Canadians, so it takes longer to make racial equity a priority in most people’s minds.” Racial diversity, however, is not a prerequisite to anti-racism work. Anti-racism is the ability to recognize systems, policies, and power, as the root of racial inequality.31

Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic was frequently mentioned by Ontario schools as a key challenge. One elementary school principal from Central Ontario explained, “School closures and COVID interruptions have greatly impacted the depth of learning and conversation around anti-racism. Greater continuity would certainly be beneficial to these efforts.” As we move forward and emerge from the initial shock of this pandemic, it is critical that we have a clear and consistent plan in place to advance equity and anti-racism at regional, jurisdictional, as well as pan-Canadian levels.

In June 2022, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Child (UNCRC) reported on Canada’s lack of progress on children’s rights and well-being. In particular, the UNCRC recommended that Canada take immediate actions to ensure equal access to quality education for all children, which includes improving pan-Canadian data collection efforts to facilitate nationwide monitoring and analysis of the situation of children, particularly those in situations of vulnerability.32

In 2019, Canada announced a three-year Anti-Racism Strategy, which outlined an investment of $6.2 million out of a total pledge of $45 million towards improved data collection efforts.33 Other federal institutions such as Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Global Affairs Canada, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) have also developed plans for equity and anti-racism.34 Critics argue, though, that “strategies and secretariats won’t do [all this work]” unless legislation that holds systems and individuals legally accountable is also introduced.35 Collecting disaggregated data, including race-based data, is a fundamental step in institutional accountability because it provides evidence on where gaps exist and where further attention is needed.

Statistics Canada is an agency of the Government of Canada that is responsible for producing and running analysis on data about all 13 provinces and territories. In 1996, Statistics Canada began to ask Canadians whether they identify as a “visible minority” in the Census of Population, yet there remains no mention of “race” in this data collection.36 Consequently, these data cannot be disaggregated into specific racial groupings, preventing systems from knowing what disparities exist among different populations of people, which is a prerequisite for working to combat the inequities.

Instead, Statistics Canada is attempting to respond to demand for race-based data through crowdsourced surveys and increasing the representation of marginalized groups in their samples.37 Given that the census dataset underpins and enables further analysis across data collections in every sector, its lack of disaggregated race-based data is slowing Canada’s progress towards more equitable institutional decision-making.38 As provinces and territories work towards advancing anti-racism, it is important to ask how federal leadership could play a role in supporting these efforts, as well as what critical understandings are necessary in guiding this work, and how to cultivate them.

While anti-racism policymaking—regional, provincial, and federal—has begun in Canada, this work is currently piecemeal and lacking consistency, possibly due to varying understandings about its rationale or purpose. In reviewing legislation and non-legislation progress across the country, in addition to a closer look at publicly funded schools in Ontario, PFE has three recommendations on how to move forward with regards to equity and anti-racism policy.

1. Name the problem

Currently, only 40% of Ontario school boards have published anti-racism statements on their websites, and 26% have an equity policy that does not include any mention of race or racism. Naming the problem is a crucial step towards removing societal taboos around race and creating an environment where students and staff feel safe to critically engage in conversations around race and racism. Public policies and strategies that name the problem signal an understanding of anti-racism and how power, privilege, and systemic discrimination have contributed to current societal inequities.

2. Data collection is a good start, but it’s only the start

We know that inequity exists, but often we lack the data to address it. Collecting disaggregated identity-based data is a critical starting point that allows for the identification of inequities present in our systems, but it is only one piece of a puzzle that also includes data development (e.g., identifying indicators, creating collection tools, etc.), public reporting, and accountability mechanisms. Beyond collecting the data, this information should be regularly and publicly reported to promote institutional transparency and accountability. Furthermore, it is critical that individuals, groups, and communities who have been historically impacted by discrimination are consulted throughout this process. For example, British Columbia’s Anti-Racism Data Act was co-developed with Indigenous leadership and establishes a process for government to request permission from Indigenous communities to use their data.39

3. This is a process that needs to involve everyone, but especially individuals and groups historically impacted by discrimination

Less than one-third of Ontario school boards report using a parent survey or a school climate survey, and only 37% of Ontario schools reported partnering with community-based organizations in their anti-racism and equity work. Consistent efforts to understand school climate and address negative impacts on students, staff, and families can help create safer and more equitable learning environments that support all students to thrive. However, efforts should go beyond simply providing opportunities through periodic surveys, and instead dedicate time and resources to seeking out and building partnerships with individuals, groups, and community organizations who have been historically impacted by discrimination. Instead of being viewed as one step in the decision-making process, listening to these voices, perspectives, and lived experiences needs to be centred throughout the process. One way to facilitate this approach is by evaluating systems to ensure that equity-seeking groups have a mechanism to voice their concerns in addition to developing accountability measures that ensure that the appropriate follow-up actions are undertaken. School boards need government support in doing this work, both logistically with regards to time and resources, but also with respect to direction and leadership, which is where those community partnerships and marginalized voices could be an impactful guide.

1 Government of Canada. 2019. “Building a Foundation for Change: Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy 2019–2022.” Accessed October 17, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/anti-racism-engagement/anti-racism-strategy.html.

2 Government of Ontario. 2017. “Anti-Racism Act.” Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17a15; Government of British Columbia. 2022. “Anti-racism Data Act.” Accessed July 15, 2022. https://engage.gov.bc.ca/antiracism/data-act/; Nova Scotia Legislature. 2022. “Bill No. 96 (as passed): Dismantling Racism and Hate Act.” Accessed June 20, 2022. https://nslegislature.ca/legc/bills/64th_1st/3rd_read/b096.htm.

3 Kendi, Ibram X. 2019. How to be an antiracist. New York: Penguin Random House LLC.

4 Government of Canada. 2022. “Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian Residential Schools”. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/interlocutor-interlocuteur/

5 Toronto Police Service. 2022. Race & Identity Based Data Collection Strategy Understanding Use of Force & Strip Searches in 2020 Detailed Report. https://www.tps.ca/media/filer_public/93/04/93040d36-3c23-494c-b88b-d60e3655e88b/98ccfdad-fe36-4ea5-a54c-d610a1c5a5a1.pdf.

6 Oriola, Temitope. 2022. “The Toronto Police Apology for Its Treatment of Racialized People Is Meaningless without Action.”

The Conversation. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://theconversation.com/the-toronto-police-apology-for-its-treatment-of-racialized-people-is-meaningless-without-action-185262.

7 Chadha, Ena, Suzanne Herbert, and Shawn Richard. February 28, 2020. Review of Peel District School Board. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-review-peel-dsb-school-board-report-en-2022-05-26.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2022.

8 Kendi, Ibram X. 2019. How to be an antiracist. New York: Penguin Random House LLC.

9 Merriam-Webster. 2018. “Definition of EQUALITY.” Merriam-Webster.com. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/equality.

10 McGill University. 2019. Equity at McGill: Definitions. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.mcgill.ca/equity/resources/definitions.

11 Government of Canada. 2021. Best practices in Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in Research. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx

12 Merriam-Webster. 2019. “Definition of INCLUSION.” Merriam-Webster.com. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inclusion.

13 Merriam Webster. 2022. “Definition of RACISM.” Merriam-Webster.com. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/racism.

14 Government of Ontario. 2017. “Ontario’s anti-racism strategic plan”. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-anti-racism-strategic-plan; Government of Nova Scotia. (n.d.). “Office of Equity and Anti-Racism Initiatives”. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://beta.novascotia.ca/government/equity-and-anti-racism-initiatives; Government of Alberta. 2022. “Taking action against racism”. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.alberta.ca/taking-action-against-racism.aspx; Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. 2022. “Ministerial Committee on Anti-Racism Continuing to Take Action”. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2022/exec/0406n01/; Government of New Brunswick. 2021. “Commissioner on systemic racism”. Accessed August 3, 2022. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/csr-crs/en.html#3

15 Khan, Themrise. 2022. “Canada needs to get on with tackling racism in concrete ways.” Policy Options, July 8, 2022.

https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/july-2022/canada-wrong-on-racism/.

16 Government of British Columbia. 2022. “New Anti-Racism Data Act Will Help Fight Systemic Racism | BC Gov News.” Accessed

October 2, 2022. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022PREM0027-000673.

17 Government of British Columbia. 2022. “Anti-racism data legislation becomes law.” Accessed July 15, 2022. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022AG0084-000872

18 Nova Scotia Legislature. 2022. “Bill No. 96 (as passed): Dismantling Racism and Hate Act.” Accessed June 20, 2022. https://nslegislature.ca/legc/bills/64th_1st/3rd_read/b096.htm.

19 Government of Nova Scotia. 2022. “Legislation will address systemic racism, hate and inequity.” Accessed June 20, 2022.

https://novascotia.ca/news/release/?id=20220324002.

20 Lewis, Stephen. June 9, 1992. Report of the Advisor on Race Relations to the Premier of Ontario, Bob Rae. Accessed on November 3, 2022. https://www.siu.on.ca/pdfs/report_of_the_advisor_on_race_relations_to_the_premier_of_ontario_bob_rae.pdf

21 Government of Ontario. 2017. “Anti-Racism Act, 2017, S.O. 2017, c. 15.” Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17a15#BK2

22 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2017. “Ontario’s Education Equity Action Plan.” Accessed August 15, 2022. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/about/education_equity_plan_en.pdf.

23 Rabbit, Chevi. 2022. “Alberta stops the anti-racism act from moving forward.” Toronto Star, April 26, 2022. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2022/04/26/alberta-stops-the-anti-racism-act-from-moving-forward.html?rf

24 Government of Manitoba. 2017. “Creating Racism-Free Schools through Critical/Courageous Conversations on Race.” Accessed October 10, 2022, https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/docs/support/racism_free/index.html.

25 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021. “Board Improvement and Equity Planning with Demographic Data.” Memorandum, September 20, 2021.

26 Government of Ontario. 2022. “Fact Sheet 9: Ethnic origin and visible minorities.” Accessed October 2, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/document/2016-census-highlights/fact-sheet-9-ethnic-origin-and-visible-minorities#:~:text=Almost%20Three%20in%20Ten%20Ontarians%20Identify%20as%20Visible%20Minorities,-In%202016%2C%203%2C885%2C585&text=These%20individuals%20comprised%2029.3%25%20of,visible%20minorities%20(7.7%20million).

27 Munroe, Tanitiã. 2022. “If I Could Change One Thing in Education: Community-School Partnerships Would Be Top Priority.”

The Conversation, August 21, 2022. https://theconversation.com/if-i-could-change-one-thing-in-education-community-school-partnerships-would-be-top-priority-188189.

28 Munroe, Tanitiã. 2022. “If I Could Change One Thing in Education: Community-School Partnerships Would Be Top Priority.”

The Conversation, August 21, 2022. https://theconversation.com/if-i-could-change-one-thing-in-education-community-school-partnerships-would-be-top-priority-188189.

29 Jewell, Tiffany. 2020. This Book is Anti-Racist: 20 Lessons on how to Wake Up, Take Action, and Do the Work. London, UK: Francis Lincoln Children’s books.

30 Safir, Shane, Jamila Dugan, Carrie Wilson, and Christopher Emdin. 2021. Street Data: A Next-Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin.

31 Kendi, Ibram X. 2019. How to be an antiracist. New York, N.Y.: Penguin Random House LLC.

32 United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. 2022. “Concluding observations on the combined fifth and sixth reports of Canada.” Accessed July 18, 2022. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CRC/Shared%20Documents/CAN/CRC_C_CAN_CO_5-6_48911_E.pdf.

33 Government of Canada. 2019. “Building a foundation for change: Canada’s anti-racism strategy 2019–2022.” Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/pch/documents/campaigns/anti-racism-engagement/ARS-Report-EN-2019-2022.pdf.

34 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2022. “Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada: Anti-Racism Strategy 2.0.” Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/documents/pdf/english/corporate/anti-racism/anti-racism-strategy-2.pdf; Government of Canada. 2021. “Letter on Implementation of the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity and Inclusion.” Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/corporate/clerk/call-to-action-anti-racism-equity-inclusion-federal-public-service/letters-implementation/3/global-affairs-canada.html; Royal Canadian Mounted Police. 2022. “Change at the RCMP.” Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/change-the-rcmp.

35 Khan, Themrise. 2022. “Canada needs to get on with tackling racism in concrete ways.” Policy Options, July 8, 2022.

https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/july-2022/canada-wrong-on-racism/.

36 Lau, Bryony. 2021. “Census 2021: Canadians are talking about race. But the census hasn’t caught up.” The Conversation, May 3, 2021. https://theconversation.com/census-2021-canadians-are-talking-about-race-but-the-census-hasnt-caught-up-158343.

37 Statistics Canada. 2019. “Crowdsourcing.” Accessed June 20,2022. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/our-data/where/crowdsourcing.

38 Lau, Bryony. 2021. “Census 2021: Canadians are talking about race. But the census hasn’t caught up.” The Conversation, May 3, 2021. https://theconversation.com/census-2021-canadians-are-talking-about-race-but-the-census-hasnt-caught-up-158343.

39 Government of British Columbia. 2022. “New Anti-Racism Data Act Will Help Fight Systemic Racism.” Accessed October 2, 2022.

https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022PREM0027-000673.

Chadha, Ena, Suzanne Herbert, and Shawn Richard. February 28, 2020. Review of Peel District School Board. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-review-peel-dsb-school-board-report-en-2022-05-26.pdf.

Government of Alberta. 2022. “Taking action against racism”. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.alberta.ca/taking-action-against-racism.aspx

Government of British Columbia. 2022. “Anti-racism Data Act.” Accessed July 15, 2022. https://engage.gov.bc.ca/antiracism/data-act/

Government of British Columbia. 2022. “Anti-racism data legislation becomes law.” Accessed July 15, 2022. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022AG0084-000872

Government of British Columbia. 2022. “New Anti-Racism Data Act Will Help Fight Systemic Racism | BC Gov News.” Accessed October 2, 2022. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022PREM0027-000673.

Government of Canada. 2019. “Building a foundation for change: Canada’s anti-racism strategy 2019–2022.” https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/pch/documents/campaigns/anti-racism-engagement/ARS-Report-EN-2019-2022.pdf.

Government of Canada. 2019. “Building a Foundation for Change: Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy 2019–2022.” Accessed October 17, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/anti-racism-engagement/anti-racism-strategy.html.

Government of Canada. 2021. “Letter on Implementation of the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity and Inclusion.” Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/corporate/clerk/call-to-action-anti-racism-equity-inclusion-federal-public-service/letters-implementation/3/global-affairs-canada.html

Government of Canada. 2022. “Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian Residential Schools”. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/interlocutor-interlocuteur/

Government of Manitoba. 2017. “Creating Racism-Free Schools through Critical/Courageous Conversations on Race.” Accessed October 10, 2022, https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/docs/support/racism_free/index.html.

Government of New Brunswick. 2021. “Commissioner on systemic racism”. Accessed August 3, 2022. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/csr-crs/en.html#3

Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. 2022. “Ministerial Committee on Anti-Racism Continuing to Take Action”. Accessed August 2, 2022.https://www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2022/exec/0406n01/

Government of Nova Scotia. 2022. “Legislation will address systemic racism, hate and inequity.” Accessed June 20, 2022. https://novascotia.ca/news/release/?id=20220324002.

Government of Nova Scotia. (n.d.). “Office of Equity and Anti-Racism Initiatives”. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://beta.novascotia.ca/government/equity-and-anti-racism-initiatives

Government of Ontario. 2017. “Anti-Racism Act, 2017, S.O. 2017, c. 15.” Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17a15#BK2

Government of Ontario. 2017. “Anti-Racism Act.” Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17a15;

Government of Ontario. 2017. “Ontario’s anti-racism strategic plan”. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-anti-racism-strategic-plan

Government of Ontario. 2022. “Fact Sheet 9: Ethnic origin and visible minorities.” Accessed October 2, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/document/2016-census-highlights/fact-sheet-9-ethnic-origin-and-visible-minorities#:~:text=Almost%20Three%20in%20Ten%20Ontarians%20Identify%20as%20Visible%20Minorities,-In%202016%2C%203%2C885%2C585&text=These%20individuals%20comprised%2029.3%25%20of,visible%20minorities%20(7.7%20million).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2022. “Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada:

“Anti-Racism Strategy 2.0.” Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/documents/pdf/english/corporate/anti-racism/anti-racism-strategy-2.pdf

Jewell, Tiffany. 2020. This Book is Anti-Racist: 20 Lessons on how to Wake Up, Take Action, and Do the Work. London, UK: Francis Lincoln Children’s books.

Kendi, Ibram X. 2019. “How to be an antiracist”. New York: Penguin Random House LLC.

Khan, Themrise. 2022. “Canada needs to get on with tackling racism in concrete ways.” Policy Options, July 8, 2022. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/july-2022/canada-wrong-on-racism/.

Lau, Bryony. 2021. “Census 2021: Canadians are talking about race. But the census hasn’t caught up.” The Conversation, May 3, 2021. https://theconversation.com/census-2021-canadians-are-talking-about-race-but-the-census-hasnt-caught-up-158343.

Lewis, Stephen. June 9, 1992. Report of the Advisor on Race Relations to the Premier of Ontario, Bob Rae. Accessed on November 3, 2022. https://www.siu.on.ca/pdfs/report_of_the_advisor_on_race_relations_to_the_premier_of_ontario_bob_rae.pdf

McGill University. 2019. Equity at McGill: Definitions. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.mcgill.ca/equity/resources/definitions.

Merriam Webster. 2022. “Definition of RACISM.” Merriam-Webster.com. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/racism.

Merriam-Webster. 2019. “Definition of INCLUSION.” Merriam-Webster.com. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inclusion.

Merriam-Webster. 2018. “Definition of EQUALITY.” Merriam-Webster.com. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/equality.

Munroe, Tanitiã. 2022. “If I Could Change One Thing in Education: Community-School Partnerships Would Be Top Priority.” The Conversation, August 21, 2022. https://theconversation.com/if-i-could-change-one-thing-in-education-community-school-partnerships-would-be-top-priority-188189.

Nova Scotia Legislature. 2022. “Bill No. 96 (as passed): Dismantling Racism and Hate Act.” Accessed June 20, 2022. https://nslegislature.ca/legc/bills/64th_1st/3rd_read/b096.htm.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2017. “Ontario’s Education Equity Action Plan.” Accessed August 15, 2022. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/about/education_equity_plan_en.pdf.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2021. “Board Improvement and Equity Planning with Demographic Data.” Memorandum, September 20, 2021.

Oriola, Temitope. 2022. “The Toronto Police Apology for Its Treatment of Racialized People Is Meaningless without Action.” The Conversation. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://theconversation.com/the-toronto-police-apology-for-its-treatment-of-racialized-people-is-meaningless-without-action-185262.

Rabbit, Chevi. 2022. “Alberta stops the anti-racism act from moving forward.” Toronto Star, April 26, 2022. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2022/04/26/alberta-stops-the-anti-racism-act-from-moving-forward.html?rf

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. 2022. “Change at the RCMP.” Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/change-the-rcmp.

Safir, Shane, Jamila Dugan, Carrie Wilson, and Christopher Emdin. 2021. Street Data: A Next-Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin.

Statistics Canada. 2019. “Crowdsourcing.” Accessed June 20,2022. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/our-data/where/crowdsourcing.

Toronto Police Service. 2022. “Race & Identity Based Data Collection Strategy Understanding Use of Force & Strip Searches in 2020 Detailed Report”. https://www.tps.ca/media/filer_public/93/04/93040d36-3c23-494c-b88b-d60e3655e88b/98ccfdad-fe36-4ea5-a54c-d610a1c5a5a1.pdf.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. 2022. “Concluding observations on the combined fifth and sixth reports of Canada.” Accessed July 18, 2022. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CRC/Shared%20Documents/CAN/CRC_C_CAN_CO_5-6_48911_E.pdf.