Dr. Alan Sears of the University of New Brunswick examines why citizenship is a core value for long term success for students and a cohesive, democratic society.

In January of 2005 David Bell, Chief Inspector of Schools for England and Wales, reported, “Citizenship is the worst taught subject” in English schools.1 Bell was summarizing evidence collected as part of the Office of Standards in Education’s (Ofsted) examination of citizenship education across the country.2 At first glance this appeared to be very bad news for those who believed citizenship education a vital component of schooling but it was, in my view, potentially very good news. The report provided rich and detailed information about the weakness in the delivery of citizenship education, but also substantial examples of exemplary practice and real successes. The bottom line was those involved knew citizenship was the worst taught subject and why; they also had very specific examples of how it could be improved.

This information was in addition to the results from ongoing research

on citizenship education being conducted by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), which reported on both student achievement and school programming in citizenship education.3 This combination of substantial bodies of knowledge provided English citizenship educators with important data to use as a basis for the development of policy and practice. It put them miles ahead of their counterparts in most jurisdictions where little if anything was – or is – known about how citizenship education was being taught or what students were learning. This is particularly true of Canada where the knowledge base for citizenship education has been described as “weak and fragmented.”4 It would be great to know that citizenship was the worst taught subject in Canadian schools for then at least we would know much more about it than we do now. As part of the Measuring What Matters initiative the purpose of this paper is to provide some background on citizenship education in Canada and around the world to provide a basis for discussion about developing substantive ways to assess citizenship and citizenship education in Canada.

Key questions:

How does attention to citizenship in education contribute to the development of a fully educated person able to lead a productive and prosperous life?

How do jurisdictions in Canada and around the world articulate the place and value of citizenship education in public schooling and the wider society?

“Citizenship education is an important facet of students’ overall education. In every grade and course in the social studies, history, and geography curriculum, students are given opportunities to learn about what it means to be a responsible, active citizen in the community of the classroom and the diverse communities to which they belong within and outside the school. It is important for students to understand that they belong to many communities and that, ultimately, they are all citizens of the global community.”

Ontario Curriculum, 2013.5

Across the democratic world education for citizenship is affirmed as a key – if not THE key – component of education in much the same terms as the quote from the recently reformed Ontario social studies curriculum above. It is unfortunate that this high rhetorical commitment to informed and engaged citizenship as a central educational outcome has rarely been matched by a concomitant allocation of resources or actual curricular priority. An international study of civic education policies and programs in 24 countries, for example, reported in 1999 that in almost all countries education for democratic citizenship was a high priority in terms of rhetoric but a low priority for mandating programs or allocating resources.6

Over the past decade there has been effort in a number of countries and regions to transform citizenship education from an unfunded mandate with little or no capacity for realization, to an actual priority supported by substantive policies and adequate resources.7 International comparison demonstrates these efforts have met with varying degrees of success in moving from rhetoric to reality in terms of adequate support for citizenship education. Although a number of countries have proceeded apace with important contributions to curriculum policy and program development, measurement and evaluation, research, implementation and teacher development, in most cases substantive attention to these elements has been sporadic or non-existent leading to mixed results in terms of the effective implementation of programs consistent with the rhetoric of reform in the area.8

Over the past 15 years a pervasive consensus about citizenship education has been growing across the democratic world. That consensus consists of four central elements: a sense of crisis – or, more accurately overlapping crises – about the state of democratic citizenship (particularly the levels of engagement or disengagement amongst young citizens); a belief that the crises can and should be addressed by effective citizenship education; a commitment to a largely civic republican conception of citizenship emphasizing both civic agency and responsibility; and a move toward constructivist approaches to teaching and learning as best practice in citizenship education.

The three perceived crises of citizenship – ignorance, alienation, and agnosticism – are outlined in Table 1. A number of factors drive concern in these areas including very low rates of voter participation particularly among young voters, and high profile news stories about youth disaffection from society. For example, the discovery in Britain that the July 2, 2005 London bombers were British born and bred caused, amongst other things, questions about the teaching of citizenship (in particular ‘Britishness’) in the nation’s schools. Several high level commissions were struck to examine the current state of civic education and make recommendations and the national curriculum in citizenship was substantially reformed as a result.9

Table 1: Crises in citizenship10

| Crisis | Manifestations | Signs of health |

| Ignorance of civic knowledge and processes | Low levels of knowledge about the history and contemporary institutions and procedures of the formal political system and issues facing the society. | Higher scores on surveys and tests of political and social knowledge. Nuanced under-standing of issues facing the society. |

| Alienation from politics and civil society | Low levels of participation in the formal political system (especially voting) and in civil society more generally. | Higher rates of voting, more engagement with the formal political system and civil society organizations. |

| Agnosticism about the values of democracy and democratic citizenship | Rise in political and social extremism including the joining of fundamentalist political or religious causes. |

Non-violent and respectful political and social activism and engagement. |

While most jurisdictions have not experienced such traumatic events, concerns about the estrangement of particular individuals and groups from democratic society is a significant shaper of citizenship education policy around the world. A recent examination of 12 jurisdictions, including Canada, found that “perceived threats to social cohesion are ubiquitous across nations and often drive reform initiatives” in citizenship education.11

Before going on it is important to mention there is a large body of literature critiquing these perceived crises. These critiques take several forms, from outright dismissal of the crises as neo-liberal fear mongering to nuanced examinations of the degree to which they hold as well as the presentation of alternative understandings of the evidence.12 American political scientist Peter Levine, for example, has consistently argued that levels of political knowledge across generations are fairly flat and not in serious decline, and that young people are engaged in higher numbers than ever in the voluntary sector.13 Most important, perhaps, scholars such as Canada’s Paul Howe have demonstrated the impact of these crises is not equally distributed across society but disengagement is much more pronounced among members of marginalized groups.14 The contention that the crises, or aspects of them, might be “myths” does not change the fact they are significant drivers of policy and practice in citizenship education internationally.15

Around the world education, and in particular citizenship education, is seen as an important part of the solution for these crises. Since 1990 there have been significant national and supra-national initiatives to reform citizenship education in Australia, England, Singapore, the United States, and across the European Union just to name a few.16 Canada, partly because of the nature of its educational system, has not had national initiatives but a number of provinces have substantially reformed their civic education curricula in line with global trends. For example, major (and very contentious) reforms were undertaken in Québec during the Charest government and, more recently, the revision of K-12 social studies and civic education in Ontario is another example.17

These reforms consistently advocate for a civic republican conception of citizenship. As Peterson points out, “civic republicanism embodies an active conception of what it means to be a citizen, with citizenship defined as a practice.” He goes on to add this conception also includes a “broad commitment to civic obligations, the common good, civic virtue, and deliberative civic engagement.”18 The quote from the revised Ontario curriculum that begins this section is a perfect example of the civic republican approach with its emphasis on informed and active engagement in the context of fostering and enhancing community.

That is not to say that citizenship education on the ground always lives up to this vision. After a recent review of curricula and practice in Canada, Kathy Bickmore concluded:

Curricula increasingly emphasize student development of skills and multiple perspectives, and some directly teach civics and affirm ‘active’ citizenship. However, evidence from various studies of teachers and students in schools suggests that Canadian curriculum-in-practice often reflects older, less democracy-oriented versions of citizenship, and that this education does not seem to inspire in students either critical awareness or intent to participate politically.19

Table 2 illustrates the continuum from those “older, less democracy oriented” versions of citizenship education through to the civic republican and constructivist orientations advocated in policy around the world. The trend line at the top indicates the generally accepted policy direction but, as Bickmore points out, there is often a considerable policy-practice gap. Practice in particular jurisdictions and classrooms falls across this spectrum.

Before concluding this section it is important to emphasize that citizenship education is not the purview of schools alone but goes on across societies. As Constance Flanagan points out, civic education begins at home.

Considerable evidence from cross-sectional, longitudinal, and retrospective studies shows that family discussions of current events are both correlated with and highly predictive of civic actions such as voting, volunteering, raising money for charity, participating in community meetings, petitioning, and boycotting. In families that discuss controversial issues and encourage teens to hold their own opinions about those issues, youth are more knowledgeable about and interested in civic issues, better able to see and to tolerate the perspectives of others.20

Civic education begins at home and continues out into the community. Again, evidence indicates civil society involvements of various kinds, both those connected to schooling and those not, profoundly shape young people’s civic knowledge, values, and sense of efficacy.21

Table 2: Traditional and Civic Republican/ Constructivist Approaches to Citizenship Education

| Traditional | Civic republican/ constructivist | |

| Knowledge/ understanding | Fixed, focused on the right answers | Fluid, focus on diverse perspectives |

| Universal | Contextual/cultural | |

| Students | Tending to depravity | Tending to positive engagement but vulnerable |

| Recipients, empty vessels | Active builders of knowledge | |

| Compliant, passive | Agents of change | |

| Teaching and learning | Authoritarian | Authoritative |

| Didactic, rote, single perspective and outcome | Attention to prior learning, culture, multiple perspectives, dissonance and variance in outcome | |

| Society and institutions | Stable | In flux |

| Generally acceptable/right — at least in traditional forms | Always in need of re-examination and reformation | |

| Students are to accept and fit in | Students are to understand and participate in reshaping |

As Constance Flanagan points out, “There is now an impressive body of research documenting both the academic and civic benefits of young people’s engagement in community service and service-learning.”22 Her work in social psychology demonstrates some of the measureable outcomes of quality community service learning including open mindedness, social trust, and commitment to a broad common good. Kahne and Sporte examined the influence of a range of civic learning opportunities on more than 4000 students in Chicago schools and found, “The impact of civic learning opportunities and of experiencing service learning was both sizeable and substantially larger then any other measure in

our study including students’ prior commitments to civic participation.”23 Billig and her colleagues studied the outcomes from national service learning programs in the US and found similar positive correlations between service learning and a range of outcomes including commitments to present and future civic participation, the development of civic skills, an a greater sense of civic efficacy.24

While research on service learning indicates a substantial range of positive outcomes it is important to emphasize two things. First, “not just any service stimulates civic engagement.”25 Virtually all researchers in the area argue that service learning must conform to a particular set of design principles in order to be effective in fostering positive civic outcomes. These include, but are not limited to: close connection to curricular learning outcomes; student choice in identifying issues and ways to address them through community service; diversity of service opportunities; community partners who engage as mentors with students; opportunities to reflect on and celebrate learning; and clear formative assessment strategies.26 The second thing to remember is that service learning is one of a number of active learning approaches such as “following current events, discussing problems in the community and ways to respond, providing students with a classroom in which open dialogue about controversial issues is common and where students study topics that matter to them, and exposure to civic role models” that are also “highly efficacious means of fostering commitments to civic participation.”27

Finally, the general civic culture has a great impact on young people. A range of studies around the world indicate that adolescents already appear to be members of the political culture that they share with adults. If they are growing up in societies with a legacy of socialism or a strong social democratic tradition, they believe in heavier government responsibilities for certain aspects of the economy. If they are growing up within a long-standing free-market tradition, they are less likely than those from other economic traditions to believe that the government should intervene in the economy, for example, by providing jobs, controlling prices or reducing income inequality.28

It is very important to keep these other sites of citizenship education in mind both when thinking about educational policy generally and assessment of outcomes in particular.

Key question:

What knowledge, skills and dispositions (critical competencies) are developed through citizenship education and related curriculum areas?

How might progress be measured in these domains?

“Recent debates in the literature suggest that citizenship education can (and should) have three core dimensions: a cognitive dimension (knowledge and understanding); an active dimension (skills and behaviours); and an affective dimension (values and attitudes).” Pupil Assessment in Citizenship Education: Purposes, Practices and Possibilities, 2009.29

The trinity of civic competencies described in the quote above – knowledge, skills, and values – has been accepted dogma in the field for many years. The problem is not disagreement with this general framework but, rather, dispute about what it means. What knowledge, skills, and values, are important for informed and engaged citizenship? Debates about these questions are ongoing and can be vociferous.

One recent manifestation of the battle to define appropriate civic knowledge has been the angst created in Canada in response to federal government initiatives in public history and commemoration. From the rewriting of a citizenship guide for immigrants, through a refocusing of the name and mandate of a national museum, millions for “the celebration of the bi-centenary of a minor British war,” and changes to the names and symbols of branches of the Canadian armed forces, to aborted plans to examine the Canadian history curriculum across the country, the Conservative government has been repeatedly accused of attempting to fundamentally alter the way Canadians understand their country through reforming national icons, public history sites, and the teaching of history in schools.30 The surprising thing is not that attempts are being made to politicize Canadian history and the teaching of the nation to the advantage of one particular political orientation, but the assumption that this is something new. Ken Osborne has produced a large body of work demonstrating that school history has been heavily contested ground in Canada for well over 100 years, and central to those debates have been questions about how to teach about the nation – or nations – of Canada.31 Similarly, a persistent issue for Canadian citizenship education has been the search to discover or create some sense of shared national identity.32 More than twenty years ago an American observer described this search as “the quintessential Canadian issue.”33

In terms of determining what knowledge should be taught and assessed,

“the cognitive revolution” of the twentieth century has had a profound impact on educational policy around the world.34 It is the revolution in thinking about how people learn that began with Piaget, continued in the work of Vygotsky and Bruner shows up today in a range of scholarship including Howard Gardner’s work on multiple intelligences. This revolution calls for moving beyond what Gardner calls “the correct answer compromise” where knowing is reduced to “a ritualistic memorization of meaningless facts and disembodied procedures,”35 to help students develop a range of sophisticated conceptual and procedural understandings in the subject areas they study. For Gardner, this kind of understanding is “the capacity to take knowledge, skills, concepts, facts learned in one context, usually in the school context, and use that knowledge in a new context, in a place where you haven’t been forewarned to make use of that knowledge.”36

While mathematics and science education were much quicker to take up the challenge of the cognitive revolution, the last twenty years has seen a growing body of research in the area in social education generally and history education in particular. In Canada and around the world ministries of education, teachers, museum curators, public historians and scholars of history education are embracing a new approach to teaching and learning which includes knowing historical information but moves beyond that to focus on developing historical thinking. There are a number of specific frameworks for historical thinking but common to them all is an emphasis on developing student competencies with the key disciplinary processes of historical work – students are expected not only to know what historians know, but also how historians know.37

The model of historical thinking that is most influential in driving policy and curricular reform in public schooling across Canada is that developed by Peter Sexias and his colleagues at the Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness at the University of British Columbia and articulated through the Historical Thinking Project (HTP).38 The HTP sets out a framework of six historical thinking concepts that are designed to “help students think about how historians transform the past into history and to begin constructing history themselves.”39 The six concepts and the key questions they are meant to address are set out in Table 3.

Table 3: Historical thinking concepts and key questions40

| Concept | Key question | |

| Historical significance |

⇒ |

How do we decided what is important to learn about the past? |

| Primary Source Evidence |

⇒ |

How do we know what we know about the past? |

| Continuity and Change |

⇒ |

How can we make sense of the complex ows of history? |

| Cause and Consequence |

⇒ |

Why do events happen, and what are their impacts? |

| Historical Perspectives |

⇒ |

How can we better understand the people of the past? |

| Ethical Dimension |

⇒ |

How can history help us to live in the present? |

Each of the six concepts is further elaborated to illustrate the central elements involved in developing more sophisticated understanding of how historians work with them and to help students become increasingly skilled at using them to do history. There is a large and growing body of international research indicating that even elementary school students can develop relatively sophisticated levels of this kind of thinking if properly taught.41

Citizenship education is well behind history education both in terms of research on how students and teachers understand and learn content in the area, but also in terms of articulating a key set of central concepts that underlie sophisticated understandings of citizenship. There are, however, growing bodies of work in these domains. The revised Ontario social studies curriculum, for example, contains frameworks for disciplinary thinking including one on historical thinking largely modeled on the work of Seixas and his colleagues and an analogous one in civics designed to induct students into the “inquiry process and the concepts of political thinking.”42 While in my view this framework falls short for several reasons, it is a start at defining key understandings for the field and in that respect very valuable.

One of the issues for measuring progress toward effective citizenship has been the lack of clear and measurable goals. It is not that jurisdictions have not identified outcomes but just the opposite, they have identified too many. As Peter Levine points out, in the search for accountability most jurisdictions have identified hundreds of specific outcomes for citizenship education, “far more material than would be possible to cover in the amount of time allotted to social studies.” He goes on to contend that, “turning standards into long lists can lead to micromanaging teachers, favouring breadth over depth, and even trivializing important concepts.”43 As I have argued elsewhere, the field of citizenship education would do well to emulate history in defining a limited number of key concepts and processes that define proficiency in the area.

Table 4 outlines three sets of such proposed concepts or key ideas central to democratic citizenship; one developed by my colleagues and I for The Spirit of Democracy Project at the University of New Brunswick, the second proposed

by Paul Woodruff in his book, First Democracy: The Challenge of an Ancient

Idea, and the third from a recent report by leading American civic educators.44 There is considerable overlap across these lists demonstrating that it should be possible to achieve fairly wide consensus of the core ideas underlying democratic citizenship.

Table 4: Central Concepts/Ideas of Democratic Citizenship

| Spirit of Democracy project | Paul Woodruff | Youth Civic Development and Education | ||

|

|

|

While the establishment of a limited set of core concepts mirrors work in

history education, it is important to point out some key differences in the fields. Citizenship is not a well-established academic discipline in the way history is but, rather, a social status and practice. Seixas and historical thinking scholars around the world have drawn their frameworks directly from the processes of the discipline of history as practiced by historians. The field of citizenship education draws on the knowledge and processes of several disciplines such as political science, history, sociology, and social psychology. Good history, including good historical practice, is judged by the standards of the community of scholars in history, but good citizenship is a much more amorphous idea and might be expressed and judged in a wider range of circumstances.

Once a set of concepts or ideas is established, it will be necessary to set out what progress looks like in terms of developing understanding of them; particularly understanding that moves beyond “the right answer compromise” described above. The teaching and learning approach of The Spirit of Democracy Project might provide some insight here. It is rooted in social constructivism

and particularly in the work of Russian psychologist and learning theorist Lev Vygostky.45 Fundamental to this approach to teaching is the idea that knowledge is “a cultural product.”46 In other words ideas and concepts do not have inherent meanings apart from those created and negotiated by people in particular contexts. Ideas, then, are complex and fluid and may mean different things to different people. Sometimes those differences exist across time or contexts but often the same concept can be understood somewhat differently by people in the same time and place; that is, they can be contested. Take the idea of democratic government as the “the consent of the governed,” for example. Almost everyone would agree that rule by “the people” is a necessary condition for democracy but there is wide disagreement about what precisely that means. One area of contention is the question of who should constitute the governed whose consent is required. In Ancient Athens, widely acknowledged as the first democracy, those included as citizens represented a minority of the total population: women, foreigners and slaves, although certainly governed, were not asked for their consent.

In contemporary Canada while a much larger percentage of the population is entitled to play a role in selecting those who govern, not everyone is included. Under the Canada Election Act voting is restricted to citizens over the age of 18 who meet particular residency requirements. There are a number of organizations, in Canada and elsewhere, which feel that the age restrictions exclude younger people from legitimate participation in their own governance and argue that the voting age should be lowered.47 Until quite recently the Act also excluded “every person undergoing punishment as an inmate in any penal institution for the commission of any offence.”48 That provision of the Act was challenged by one inmate who argued his constitutional right to vote ought to override that section of the Election Act. The Supreme Court of Canada agreed and in May of 1993 ruled that the blanket stripping of the franchise from inmates was unconstitutional. In 1999, however, the Court upheld the amended Act that prohibited from voting only prisoners serving more than 2 years, ruling it a more limited and justifiable limitation on the constitutional right to vote.49 The point is simply this, while all agree that in democracies citizens have a right to participate in their own governance, exactly who gets included is contested.

There is also disagreement about how citizens are to give their consent. In Canada the consent of the governed is generally obtained through the election of representatives to various levels of government. At the federal and provincial levels these representatives are selected using a “first past the post” electoral system that often leads to the election of individual representatives and whole governments with much less than 50% of the popular vote. In fact, it is rare in Canada to have a government elected with more than 50% of the popular vote. Some believe this system is at least partly responsible for growing voter apathy and consequent record low turnouts at the polls because the end results are not reflective of the will of the people – the consent of the governed.50 Other jurisdictions, Italy and Israel are two examples, elect representatives proportionally with parties getting seats based on the percentage of the popular vote they obtain. This often leads to minority and coalition governments but is seen by some as more fairly representing the choices made by citizens. Again, the consent of the governed is a necessary condition for democracy, but that consent can be and is obtained in a myriad of ways.

This same kind of complexity and fluidity exists for most important civic concepts. Respect for diversity, for example, shows up as a goal in the public policy of most democracies. But how is that respect to be manifested and what, if any, restrictions should the state impose on diversity? In fact, all democratic societies both protect diversity and limit it at the same time. In Canada, for example, people have the constitutional right to both diverse opinions and free expression. If, however, that expression includes promoting hatred of certain groups of people it might be deemed illegal. In considering the tensions between respecting and honouring diversity and maintaining social cohesion several Québec writers pose a key question, “On what foundation can we argue that the State must sometimes impose limitations on recognition of diversity?”51

So, what would a complex understanding of the core concepts of citizenship

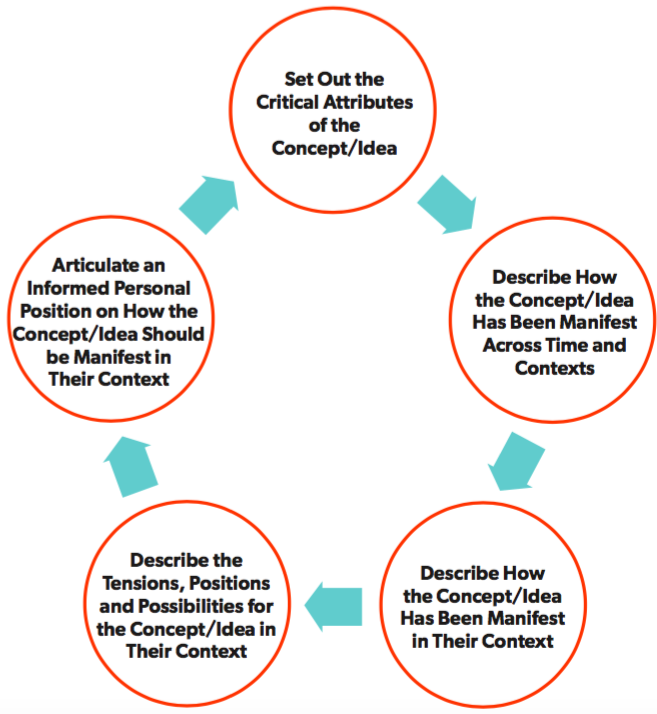

look like? At the basic level it means being able to define the concept through setting out its critical attributes. That has often been the limit of traditional teaching and assessment but creating a knowledge base to support informed and critical engagement requires much more. The next step is demonstrating an understanding of how the concept has been operationalized across time and contexts. In other words an understanding of how it has been manifest in different societies and the forces that have shaped those manifestations. Students should, for example, understand that different democratic societies have implemented the consent of the governed in different ways and that the extension of franchise rights have often come as the result of struggle. Important also is the ability to describe the way the idea or concept is manifest in their own society and to demonstrate an understanding of the contemporary tensions, positions, and possibilities for the concept or idea in their own context. Finally, students should be able to articulate a tentative position (almost all positions in a democracy should be tentative and open to exploration) of their own as to how the concept or idea should be manifest in their time and context. This kind of complex understanding lays a solid basis for engaging with others in attempting to operationalize the idea in contemporary society (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Complex Understandings of Democratic Ideas

It should be obvious that this kind of critical conceptual understanding necessitates the learning of significant amounts of specific factual information as well. Students with a critical conceptual understanding of the concept of popular sovereignty, for example, will be able to describe a range of ways in which societies have operationalized that idea including the direct democracy of Ancient Athens and various approaches to representative systems including detailed knowledge of different voting systems. In addition to this description, they will be able to discuss the strengths and weaknesses in any or all of these approaches and apply that knowledge to developing their own position on the contested concept. Later in the paper I will discuss some of the specific knowledge necessary to facilitate various kinds of civic engagement.

Virtually all citizenship educators agree that knowledge is not the only important outcome area for civic education. Students must also develop in their ability and disposition to act in ways that are consistent with democratic values. As with the knowledge area, there are competing ideas about what constitutes democratic values but, again, there are core ideas that cut across most lists. Benjamin Barber argues that the central democratic value is humility. “After all,” he writes, “the recognition that I might be wrong and my opponent right is at the very heart of the democratic faith.”52 In writing about some of the fledgling democracies in Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall, George Schöpflin makes the point that it is possible to have the form of democracy without an underlying commitment to democratic values. He writes that “post-communist systems were consensual, a consent that was expressed regularly in elections and through other institutions, but were not democratic in as much as democratic values were only sporadically to be observed.”53 Schöpflin argues that societies have what he calls first and second order rules. “First order rules include the formal regulation by which every system operates, like the constitution, laws governing elections, procedures for the settlement of conflict and the like” – the form of democracy. “Second order rules are the informal tacit rules of the game that are internalized as part of the doxa” – the spirit of democracy. In a democracy these second order rules include “key democratic values of self-limitation, feedback, moderation, commitment, responsibility, [and] the recognition of the value of competing multiple rationalities.”54

There is a growing body of evidence that approaches to citizenship education that allow for student voice and active engagement in schools and communities can have a significant impact in fostering these kinds of democratic values. As Meria Levinson points out, “Research over the past forty years, across dozens of countries, has conclusively demonstrated that students’ belief that they are ‘encouraged to speak openly in class’ is a ‘powerful predictor of their knowledge of and support for democratic values, and their participation in political discussion inside and outside school.’”55 That research also provides examples of instruments and procedures that can be used in assessing students’ commitment to democratic values.

The final area of critical competencies in citizenship is skills. All curricula in social studies and citizenship identify long lists of skills that are foundational for citizenship. For example, the revised Ontario curriculum identifies broad skill areas for development such as: “Voice informed opinions on matters relevant to their community: Adopt leadership roles in their community . . . Investigate controversial issues; and Demonstrate collaborative, innovative problem solving.”56 Each of these categories involves a large set of specific skills.

For the most part, the skills required for effective citizenship are shared with other areas of the curriculum. For example, critical literacy is fundamental to effective citizenship but is also the specific focus of language arts curricula as well as other subject areas across the curriculum. As one of the participants in a Delphi study designed to garner consensus among 100 prominent Canadians about the key features of democratic citizenship pointed out, traditional skills in reading, writing, speaking and other forms of communication are absolutely essential for effective citizenship. What is the use of the right to free speech, he contended, if a person has no ability to express him or herself effectively? Such a person has the right but no remedy – no way to access or operationalize it – and rights without remedy are meaningless.57

Citizenship education does, however, offer unique takes on some of these

skill areas. For example, Community Service Volunteers in the UK has done

a lot of work to support the citizenship education curriculum by developing civic projects in which students can engage in civic writing and civic speaking. The students are involved in writing and presenting to politicians and policy makers for a clear and genuine civic purpose rather than the contrived exercise of a classroom essay. This enhances the development of particular skills of persuasive writing and speaking.58 More needs to be done to explore the cross curricular connections of civic skills.

Key questions:

What are current approaches to measuring progress in citizenship?

Are there emerging approaches not yet in wide use?

What are potential new and innovative approaches to measuring progress in citizenship?

Civic education “has the potential to lead the way into a new generation of educational assessment . . . Multiplayer real-time simulations, digital civic portfolios and badges, authentic online civic engagement, and demonstrated off-line civic action are all promising avenues for civics instruction and assessment.”59 Meira Levinson

In the introduction to the paper I claim that little is known about either the teaching of, or achievement in, citizenship education in most jurisdictions around the world. While that is generally true there is a growing body of evidence about both these areas from academic research and national assessment programs in some countries. That knowledge provides an important baseline for discussions about moving forward in developing comprehensive approaches to assessment in civic education. In addition, the data collection and analysis techniques used in the research and assessment process provide interesting examples of techniques that might be adapted to establish substantive assessment instruments for progress in civic education in Canada. Space does not permit a detailed examination of all the research and assessment approaches so I will highlight some promising developments and then move on to propose a direction for developing civic profiles as an approach to assessment and planning in citizenship education.

Learning from research on students’ cognitive frames

A key tenet of the cognitive revolution discussed above is the belief that people come to any learning situation with a set of cognitive structures that filter and shape new information in powerful ways. Gardner calls these structures “mental representations” and argues they underlie the fact that “individuals do not just react to or perform in the world; they possess minds and these minds contain images, schemes, pictures, frames, languages, ideas, and the like.”60 The literature uses a range of different terms but generally refers to this phenomenon as prior knowledge; meaning the knowledge learners bring with them to the classroom or any other learning situation.61 Research on prior knowledge consistently shows cognitive schema to be persistent and resistant to change. “If one wants to educate for genuine understanding, then, it is important to identify these early representations, appreciate their power, and confront them directly and repeatedly.”62 To put it another way, good teaching depends on knowing what students think when they arrive in class and taking direct and repeated steps to confront their cognitive frames in order for them to consider new ideas and approaches.

There is a growing body of research from citizenship and history education helping us understand the civic ideas and theories young people hold. The work of my colleagues and I in examining students’ conceptions of key ideas related to citizenship including dissent, participation, and ethnic diversity is one example. In the area of voting, for example, our work demonstrates young people’s decision not to vote is often neither an expression of ignorance or apathy. Many of the participants in our research hold sophisticated understandings of voting, including being able to articulate the struggles of women and minorities to obtain the franchise, and they clearly know how to vote. They often tell us, however, that they either do not vote now or, if not 18, that they do not intend to vote in the future. They go on to articulate a range of reasons for why they are sceptical about voting.63 This kind of knowledge about student thinking is important in planning for civic education to effectively address this area. Current voter education programs almost always focus on increasing knowledge of voting procedures or reasons to vote but the young people in our research are often well ahead of those programs.

A significant body of research from history education demonstrates that students often share national or cultural characteristics in the cognitive frames about their own societies. Research in the US, for example, shows that a shared cognitive framework of progress and freedom is common and persistent in American students’ understandings of their national history. Other work demonstrates that other national and cultural contexts shape historical understanding in particular ways as well. High school students in Northern Ireland, for example, have much different perceptions of their national story. In contrast to American students, these young people do not believe progress, at least in terms of dealing with the religious and cultural divisions in the territory, is possible. For them, history demonstrates the substantial divisions in the country cannot be changed.64 In the Canadian context, Létourneau found Francophone Québec students’ had very well developed “mythistories” of the history of Québec and Canada. He writes, “Practically all students I tested, from Grade 11 to the university level, used a narrative that is, in a way, traditional. It refers to the timeless quest of Québécois, poor alienated people, for emancipation from their oppressors.”65 This frame is, Létourneau contends, not consistent with the most recent work of historians. Carla Peck’s work in multiethnic contexts in Vancouver demonstrates that historical understanding is also shaped by students’ particular ethnic and cultural backgrounds.66

These kinds of cognitive frames have obvious implications for civic education both in terms of how students see their particular ‘nation’ and how they

might view ideas like the common good or what constitutes appropriate civic engagement. Given that cognitive schema such as these prove persistent and resistant to change, the pedagogical implication for citizenship education is that students must both be taught to see the internal contradictions in their own narratives as well as to explore the narratives of others.67 Helping students develop more nuanced and sophisticated understanding is a long term and complex process.

These are just two small examples from a large pool of work. The point is that we are beginning to understand much more about young people’s conceptions

of key aspects of citizenship. Any assessment project should help build on that body of work because those kinds of understandings are essential for structuring appropriate curricular and pedagogical responses. Assessors can also learn from the research techniques employed in this work, some of which collected data from large populations, in developing measures to assess substantive aspects of learning related to citizenship.

Learning from research on political socialization

As I said above, much policy and practice in citizenship education is crafted in response to the three crises of citizenship: ignorance, alienation, and agnosticism. While aspects of these crises are real and need to be addressed in education, they are often presented in oversimplified fashion and therefore responses frequently take the form of blunt instruments rather than precise tools. If we take concern about declining rates of voting and participation as one example, it becomes clear that the problems are not as simple as they seem on the surface.

In his book length study, Canadian political scientist Paul Howe argues that

“at least one-third of Canadians under thirty, and probably slightly more, have largely checked out of electoral politics.”68 For Howe, declining voting rates are not the whole story but “the canary in the disengagement coal mine,” signalling much more pervasive detachment.69 Howe goes on to show that disengagement is not evenly distributed across society but far more prevalent among those with less income and less education. Richard Niemi makes the same point about disengagement in the US but extends those excluding themselves to include members of particular ethnic or racial minorities.70

A substantial amount of research from the United States affirms Howe and Niemi’s findings and indicates the gap is not only in terms of participation in political and other civic activities but in civic opportunities offered in schools. Levinson writes about the “profound civic empowerment gap” that exists for students from marginalized populations in the US and virtually every chapter

of the edited collection Making Civics Count: Citizenship Education for a New Generation details some aspects of the difference in opportunities provided to students from different socioeconomic classes or racial and ethnic groups.71

This extends to the very structures of schooling. As James Youniss points out, research demonstrates that “schools with high proportions of economically disadvantaged students tended not to have student governments. And if they had governments, students were given little voice in policy.”72

One of the key areas of differentiation emerging from research on young people’s political socialization is gender. Flanagan and her colleagues studied the political theories of young people across six nations concluding, in part, “Across all six nations, gender was consistently related to adolescents’ interpretations of the social contract.”73 Across the board females were “more likely than their male peers to be concerned about inequalities in their society and the conditions faced by marginalized groups.”74

Research conducted by my colleagues and I also demonstrates gender is an important factor in shaping the disposition to participate in civic life. Consistent with Flanagan’s findings, the young women we study are more likely to be engaged in philanthropic and social justice oriented work in their communities. When it comes to engagement with the formal political system, however, these same young women are far less likely than their male counterparts to see personal engagement as a possibility for them. They consistently express less interest in the area and indicate they feel unqualified (despite their experience in community work) to participate.75

Again, this is a very small sampling of available work but two significant implications are: first, that we need a much more nuanced understanding of civic engagement/disengagement and cannot assume that one pattern of behavior

or attitudes fit for all citizens and, second, given that civic knowledge and engagement may differ between and among groups a one size fits all approach to civic education and assessment may not be appropriate. Again, the methods of data collection and analysis used by these kinds of researchers might be valuable examples in designing assessments for civic education.

Learning from national and cross national studies of citizenship education

The increasing impetus to reform citizenship education has been accompanied, in some areas, with research to support policy and practice. Colleagues and I compared citizenship education reform across four nations (Australia, Canada, England and the US) and concluded that the English approach was by far the model to emulate.76

Concurrent with the establishment of citizenship as a statutory part of the national curriculum in 2002, the former Department for Education and Skills (DfES) commissioned the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) to conduct a multi year longitudinal study of citizenship in schools. The focus of the longitudinal study was on tracking a cohort of young people who entered secondary school in September 2002 and were the first students to have a continuous statutory entitlement to citizenship education.

In addition to the requirements of the longitudinal study, NFER completed a number of other studies commissioned by the DfEE. This was combined with including citizenship as one of the key areas to be examined during regular Ofted inspection mentioned in the introduction to this paper. What is particularly important in the development of the research base in England is the clear commitment that exists of pursuing an evidence-based approach to citizenship education.77

The NFER longitudinal study provided a substantial range of findings on student learning across the domains of citizenship: knowledge, skills, and values. It has published a number of reports that can be drawn on in the development of assessment procedures. Consideration of classroom and school climate has also played a role in the monitoring of the implementation of the National Curriculum citizenship program in England. In the early cross-sectional surveys conducted by the NFER, teachers’ reports on several aspects of classroom life in citizenship studies were subjected to factor analysis. One of the central factors influencing instruction was shown by the analysis to be “classroom climate.” High scores on the climate index showed that students “discuss and debate, bring up issues for discussion, receive unbiased information from teachers, express their views even if they disagree with teachers, and are encouraged to make up their own minds.”78

The largest international study of civic education was conducted under the auspices of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). The two-phase study of began in 1990 with the first phase consisting of the development of national case studies of the intended curriculum in civic education for 14 year-olds in participating countries.79 These were used as the basis for developing extensive testing and survey instruments used in the second phase to assess civic knowledge, skills and attitudes as well as things like classroom practice and pedagogy in the area. Initially, Canadian provinces that were members of the IEA showed no interest in participating. The Federal Government, however, was interested in the information such research might provide and it persuaded the provinces through the CMEC. The federal government provided the funding with the then Department of Secretary of State (now Canadian Heritage) putting up $50,000 and Canada was allowed to join the study late. A research team at the University of New Brunswick developed both the case study for Canada and a feasibility study for participation in Phase 2.80 The Federal Government was very interested in participating in the second phase but the CMEC balked and Canada was left out, thereby missing the opportunity to collect important base-line data on citizenship education in this country. Data that would provide both important national and provincial information – we know almost nothing about the civic knowledge, skills and dispositions of Canadian students or about teaching practices in Canadian schools – and the basis for international comparisons. Phase 2 reports are being widely used in informing policy and programming for civic education around the world.81 The IEA instruments are publicly available, however, and would be very helpful in the development of large scale, valid and reliable assessment tools.

This section provides one example each of national and international research studies in citizenship education. There are a number of other possible examples and all have the potential to provide significant guidance in the development of assessment procedures and instruments.

Learning from large scale assessment programs in citizenship

A number of educational jurisdictions mandate large-scale assessments of civic learning. In the US civics is part of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) with students assessed in the area at grades four, eight and twelve. Australia runs a similar process at years six and ten as part of its National Assessment Program. The broad areas covered in the student assessment of these programs are summarized in Table 5 on the next page.

Both assessments also include surveys for schools, teachers, and students about how citizenship is addressed in curricular, co-curricular, and extracurricular activities. Students are asked, for example, if they have the opportunity to participate in student government, express their opinion in class, or engage in community based learning experiences. This data adds to the reports of student progress by providing a picture of how civics is delivered in the jurisdictions. Analysis of the last round of NAEP assessments, for example, painted a relatively bleak picture of the delivery of civics in school.

Only a minority of eighth-grade students report that their civics classes include curricula other than the textbook or discussion of current events. Fifty-nine percent of fourth-grade students, 53 percent of eighth-grade students, and 56 percent of twelfth-grade students report that they never participate in simulations or mock trials. Nearly 70 percent of students never write letters to the newspaper or otherwise express their opinions in a public way. Only 30 percent of fourth or eighth-grade teachers report that their students engage in some form of student government. Less that 20 percent of fourth- or eighth- grade teachers organize visits from members of the community or report their students participate in community projects.83

This kind of data is invaluable in developing correlations to show relationships between particular pedagogical approaches and student progress and its collection should be part of any assessment program.

Both the NAEP and NAP publish comprehensive reports of the assessments including sample instruments and assessment scales. These will be important resources in the development of Canadian approaches to assessment in citizenship. Levine points out, however, that these kinds of assessments can be quite narrow in the areas they address. In terms of knowledge they focus overwhelmingly on national historical information and constitutional structures. “But,” he writes, “Current events and civic skills are not well measured by the NAEP. In fact, a no-stakes test taken by seniors during their final semester is not a particularly reliable measure of even the abstract and procedural knowledge that dominates the NAEP.”84 His contention is that comprehensive assessment in citizenship must include examination of engagement in civil society at the local level, the place where most citizens focus their energies. The next section focuses on a proposal that includes just that.

Table 5: Areas of assessment for NAEP and NAP civics82

| NAEP United States | NAP Australia | |

| Civic knowledge | Civics and citizenship content | |

|

|

|

| Cognitive processes for understanding civics and citizenship | ||

|

||

| Intilectual skills | Affective processes for civics and citizenship | |

|

|

|

| Civic dispositions | Civic and citizenship participation | |

|

|

“Promoting civic participation is a central purpose of schools, and so it is central to the work of teachers.” Keith C. Barton85

Citizenship education around the world is, officially at least, largely focused on fostering informed and responsible civic engagement. A problem is, however, just as citizenship itself is an amorphous term that can be bent and twisted in a number of directions, civic engagement is also often used more as a slogan than precise descriptor. The elementary curriculum in British Columbia, for example, has as an outcome at several grade levels, that students should develop and implement a “plan of action to address a selected school, community, or national problem or issue.”86 Suggestions for what actions or kinds of engagement might be included in those plans are sparse and vague and no specific criteria for assessment of civic engagement are ever provided. There is a requirement to assess “whether or not [students] understand their responsibility of what it means to be an active citizen” but nothing more is offered to indicate what that understanding might entail.87

This is not to single out BC, because the precise elements for well rounded and sophisticated civic engagement are simply not laid out in policy and curriculum documents anywhere. This raises a significant challenge for assessing progress in this realm across the years of public schooling. What does progress in civic engagement look like? Is it simply more activity? If so, what activity counts? What is the connection between civic action/engagement and knowledge? Most advocates, after all, argue not just for engagement but also for informed or, more commonly, responsible engagement.

There is a range of ways in which citizens participate in their communities and beyond and civic education curricula explicitly or implicitly acknowledge them all as worth civic engagement. It is, however, unreasonable to expect that all citizens will participate to a great degree in all areas all the time.

In his book The Ethics of Voting, American philosopher Jason Brenan makes

the point that even voting, seemingly the simplest of political acts, is more complicated than we might think. While the act of voting itself is relatively easy, responsible voting – voting with a well developed sense of what the issues are, the positions various candidates and parties take on those issues, and well grounded ideas about the possible consequences of those positions – is much more time consuming and difficult. In his words, “It is easy to vote – just show up and check a few boxes – but it is hard to vote well.”88 Brennan’s argument is that a well-balanced democratic society requires a range of civic engagement and since citizens simply cannot spend the requisite time to engage in all areas well, they would be better to focus their participation in areas where they have interest and ability to make the most significant contribution.

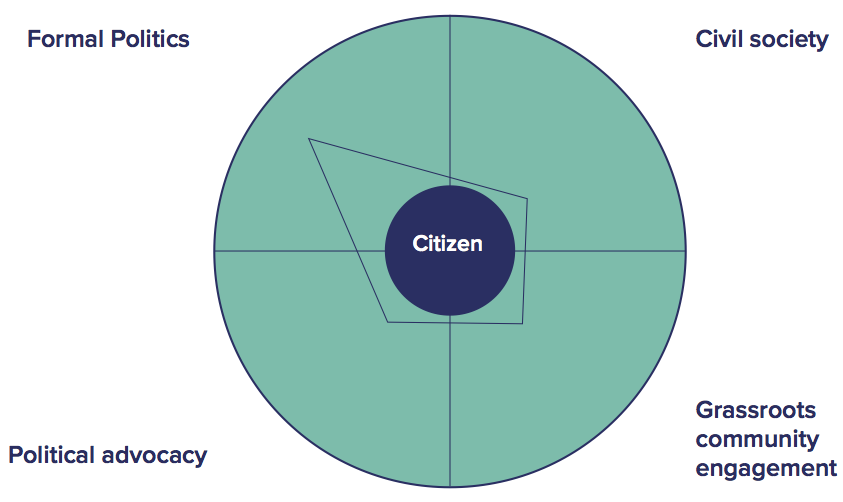

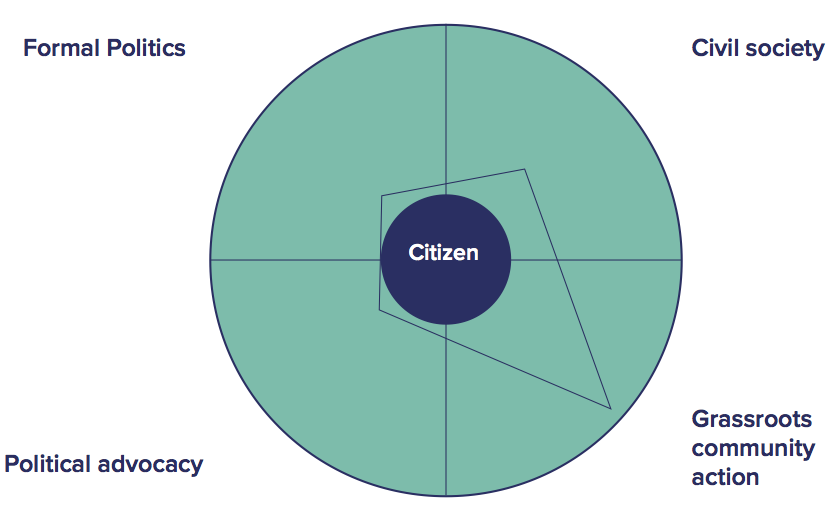

While few would go as far as Brennan in suggesting that many citizens should not vote because they do not have the capacity or inclination to vote responsibly, his point that productive civic engagement takes a range of forms and that the common good is best served by individuals focusing their own participation in areas that fit their interests, strengths, and opportunities is a powerful one. But if everyone’s civic engagement is different, how can it be measured in ways that might be meaningful to education officials, teachers, parents, and students themselves? I suggest that the development of civic engagement and knowledge profiles outlined below as a way forward. These profiles will provide a picture of the civic engagement and knowledge of individuals and groups across four domains: formal politics; political advocacy; civil society; community/grassroots action (see Tables 6 & 7).

Table 6: Domains of civic engagement

| Formal politics | Political advocacy | |

| Characterized by engagement in the formal political system including: voting, attending political meetings and rallies, joining political parties, participating in campaigns, presenting to legislative committees, running for office, etc. | Characterized by engagement outside of the structures of the formal political system with the intention of a ecting change within, through, or to those structures including: signing petitions, boycotting, demonstrating, lobbying, participating in social media campaigns, writing or presenting in the media, etc. | |

| Civil society | Grassroots/community action | |

| Characterized by engagement within ongoing civil society organizations or institutions including: labour unions, religious groups, environmental organizations, service clubs, heritage groups, youth organizations, academic and professional societies, and other non-governmental organizations. | Characterized by peripheral, sporadic, or temporary engagement with a community group or project including: volunteering, working on short-term projects, involvement with community sporting or cultural events, etc. | |

Table 7: Domains of civic engagement knowledge

| Formal politics | Political advocacy | |

| Characterized by theoretical and applied knowl- edge of the formal political system including: the history of its development, underlying principles, central structures, key issues and controversies re- lated to its functioning, comparative context (how it compares to other systems both democratic and non-democratic), etc. | Characterized by theoretical and applied knowl- edge of the range of ways of citizen engagement outside of the structures of the formal political sys- tem with the intention of a ecting change within, through, or to those structures including: signing petitions, boycotting, demonstrating, lobbying, participating in social media campaigns, writing or presenting in the media, etc. | |

| Civil society | Grassroots/community action | |

| Characterized by theoretical and applied knowledge of civil society including the organizations that make it up and the ways they operate to provide social goods and a check on state power and influence. | Characterized by theoretical and applied knowl- edge of the community including the individuals and groups that make it up, key issues facing it, the range of opportunities for long-term and short-term, formal and informal engagement at the community level including: volunteering, working on short-term projects, involvement with commu- nity sporting or cultural events, etc. | |

Before moving on to describe how civic profiles will work, it is important to make several points about the categories. First, together they are a heuristic device or guide for understanding a particular phenomena (civic engagement) and not intended to imply that engagement only takes place in these discreet silos. Indeed, it is obvious that there is often considerable overlap. Civil society organizations, for example, engage both in political advocacy and in direct community action. Similarly, volunteering might take place in the context of a civil society organization. The difference in categorization here is indicative of the participant’s connection to that organization. Someone who engages as a member and participates in the shaping of policy and practice of that organization would fit the civil society category while another person who simply shows up for a volunteer shift from time to time but takes no substantial part in the organization itself would fit the grassroots/community action category. Despite having porous borders, the categories do represent discreet ways that both the literature and individuals describe civic engagement and are therefore helpful in understanding the range of ways individuals and groups engage.

Second, the labeling of one category as “Formal Politics” is not to imply that other categories are apolitical. While citizens themselves often make firm distinctions between activities they see as political and non-political, the view here is that any activities that have implications for our common life together – the common good – are political.

Third, these are meant to be understood broadly both historically and geographically. In other words, knowledge in any of these categories is not meant to be confined to the present. Finally, the examples of types of engagement that fit each category are designed to be illustrative rather than definitive. There are many more possible examples for each domain.

If civic engagement takes place across a spectrum of domains, accurately assessing any given citizen’s level of civic engagement will involve measuring their involvements across that spectrum. Figure 3 provides a sample of a hypothetical citizen’s engagement.

Figure 2: Civic engagement Profile

This citizen is pretty typical of the young people studied in some of my own research.89 She is fairly substantially involved in community action doing regular volunteer shifts at the local community kitchen and serving on the organizing committee for one charity’s annual fundraising activities. She is a regular member of a national youth organization but does not take any leadership role so scores in the moderate range in the civil society category. She explicitly avoids involvement in both formal politics and political advocacy so scores in the minimal range in both those areas. It is interesting to compare this engagement profile with the same hypothetical citizen’s civic knowledge profile illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Civic engagement profile

Figure 3: Civic knowledge Profile

While this young woman participates extensively in the volunteer sector her knowledge of that sector, beyond the particular organizations with which

she works, is relatively weak. She knows little about the range of community engagement opportunities available in her community and even less about how organizations and individuals in this sector shape civic life and policy.

Figure 3: Civic knowledge profile

the range of associations that make up civil society or their role in advancing the civic conversation. Democratic political theorists, however, articulate an important role for civil society in enhancing the common good. Peter Levine puts it this way,

A strong civil society reduces the burdens on the state to provide public goods. It monitors and holds accountable both the state and the market. It permits groups with a diversity of norms and mores to form, so that the whole population need not agree about everything to cooperate effectively. And it enhances the political power of individuals who lack money, offices, and connections.90

Levine goes on to argue that many people engage in civic life mainly through civil society organizations or grassroots community initiatives but civics curricula almost never give sustained attention to teaching young citizens anything about it as a political force. Our young citizens’ civic knowledge profile reflects that reality.

Ironically, given her own stated resistance to overt political activity in either formal politics or advocacy, these are the domains where our citizen’s knowledge appears to be the greatest. That is because these areas receive considerable focus in school curricula. Everywhere in the democratic world the structure of governments features prominently in civics, social studies, and history curricula. In recent years, part of the response to the civic disengagement crises discussed above has been a focus on civic agents in curricula, on people who make – or made – a difference through various kinds of political advocacy. The struggle for women’s rights is a common example of this trend. For example, the grade seven social studies curriculum in New Brunswick calls for students to “examine how women became more empowered through their role in the social reform movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” Similarly, Alberta requires that students in grade five “assess, critically, how the Famous Five brought about change in Canada.”91 Our young citizen’s civic knowledge profile makes sense in light of this curricular focus.

So, what do these profiles tell us about our young citizen? The engagement profile indicates she is quite active in two domains and not at all active in the two others. Should that concern us? After all, it is probably impossible for any citizen to be very active across the spectrum at any one time. Research demonstrates that a range of factors including life stage, socio-economic status, interests, political dispositions, and opportunities impact people’s engagement choices.92 Should we be satisfied that this young woman is very engaged in service opportunities in her community while eschewing involvement in formal politics?

Ultimately, the standards for a strong civic engagement profile will have to be established through much thought and discussion and it should certainly be possible for different profiles to be considered strong. It seems to me, however, that this profile is unbalanced in ways that should concern us. While not everyone will be engaged in formal politics to a substantial degree, – it is unlikely, for example, that the majority of citizens will ever run for office or even join a political party – to completely exclude oneself from the domain is not healthy for democracy. A strong profile then would meet minimum standards in each category with definite areas of strength in some. That profile will be expected to shift in different stages of a citizen’s life.

Similarly, our young citizen’s knowledge profile is quite unbalanced. She certainly could know much more about political advocacy but her understandings of the civic potential of community action and civil society are particularly weak. This reflects a definite lack of attention to the civic and political aspects of these domains in both civic curricula and service learning programs. Levine points out that while most citizens focus their own engagement in their communities and the volunteer section, curricula and assessment in civic education focus overwhelmingly on constitutional and legal structures of governments.93

While the growing emphasis on service learning programs has the potential to enhance civic learning in the domains of civil society and community action, most programs are so superficial and apolitical that very little substantial

civic learning takes place. Reviewing literature on almost 20 years of service learning programs in England, for example, Andrew Peterson and Paul Warwick found a “consistent lack of real comprehension and application of the learning prerequisite central to the effective and meaningful community engagement of young people.”94 James Youniss says similar things about service learning in the US making the point that “not just any service stimulates civic engagement.”95 Moving young citizens toward a more balanced civic knowledge profile will involve substantial changes to both curricula and service learning programs.

It is my contention that using civic profiles as one aspect of assessment for citizenship has great potential. There are currently survey and test instruments available to assess both students’ actual and potential or latent engagements. A survey instrument employed in some of my own research provide the data for our research team to map the civic engagement of 2000 high school students from the Maritimes and Alberta and a number of questions on the IEA survey of 90,000 students from 28 countries asked 14 year-olds about the ways in which they intend to participate in the future.96 These and others could be used as the basis for developing instruments to map engagement across the four domains. Displaying results graphically as above provides a strong picture of the engagement of individual students but it would also be possible to graph whole populations using mean scores. Factor analysis would also allow the identification and portrayals of subtypes within populations.

In terms of knowledge, large-scale assessments from around the world have demonstrated it is possible to test for conceptual and procedural knowledge as well as the recall of basic facts. Taking Levine’s point that these would have to be expanded to include assessment of civic knowledge across the four domains outlined above, it is possible to design instruments that would allow the creation of accurate knowledge profiles. Again these could be graphed on the individual and group level and would provide very valuable feedback for students, teachers, and policy makers.

Several years ago colleagues and I published the results of comparative analysis of curriculum reforms in citizenship education in four countries: Australia, Canada, England and the US.97 We identified seven elements of capacity building that make for successful implementation of curricular reform in the area and concluded that Canada lagged behind the other nations in virtually all of them. Canadian teachers had similar curricular mandates to their counterparts internationally but were being provided with almost none of the structural supports necessary to successfully achieve those mandates.

One of the features we identified as fundamental to successful reform was research and development. Much of the research knowledge in other countries comes from their attempts to assess student learning and pedagogical practice through both academic research projects and large-scale assessments such as those described above. Reporting the results of such assessments, particularly when the news is not good, can often lead to increased commitment to activity in some of the other areas fundamental to successful programs such as curriculum and materials development, teacher development, and the provision of adequate funding. The initiative to develop substantial ways to assess progress on citizenship goals in schools, then, has the potential to greatly enhance Canada’s capacity to deliver high quality programs in citizenship.

Endnotes

- Bell, David. “Address to the Hansard Society.” Paper presented at the The Hansard Society, London, January 17 2005.

- Ofsted. “Citizenship in Secondary Schools: Evidence from Ofstead Inspections (2003/2004).” London: Office of Standards in Education, 2005.

- Cleaver, Elizabeth, Eleanor Ireland, David Kerr, and Joana Lopes. “Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study: Second Cross-Sectional Survey 2004. Listening to Young People: Citizenship Education in England.” Berkshire: National Foundation for Educational Research, 2005. See also, Keating, Avril, David Kerr, Thomas Benton, Ellie Mundy, and Joana Lopes. “Citizenship Education in England 2001-2010: Young People’s Practices and Prospects for the Future: The Eighth and Final Report from the Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study (Cels).” London: Department for Education, 2010.

- Hughes, Andrew S., Murray Print, and Alan Sears. “Curriculum Capacity and Citizenship Education: A Comparative Analysis.” Compare 40, no. 3 (2010), p. 305.

- Ontario Ministry of Education. “The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 and 10 Canadian and World Studies: Geography, History, Civics (Politics).” edited by Ministry of Education. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education 2013, p. 9.

- Torney-Purta, J., J. Schwille, and J. A. Amadeo. Civic Education across Countries: Twenty-Four Case Studies from the Iea Civic Education Project. Amsterdam: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, 1999.

- See, for example, Carnegie Corporation of New York, and CIRCLE: Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement. “The Civic Mission of Schools.” New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York and CIRCLE: Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement., 2003. Kerr, David, Avril Keating, and Eleanor Ireland. “Pupil Assessment in Citizenship Education: Purposes, Practices and Possibilities. Report of a CIDREE Collaborative Project”. Slough: NFER/ CIDREE, 2009. Arthur, James, Ian Davies, and Carole Hahn, eds. The Sage Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Democracy. London: Sage, 2008. Hughes, Print and Sears, “Curriculum.”

- Hughes, Print and Sears, “Curriculum.”

- See, Ajegbo, Sir Keith, Dina Kiwan and Seema Sharma. Diversity and Citizenship Curriculum Review. London: Department for Education and Skills, 2007. Goldsmith QC, Lord. Citizenship: Our Common Bond. London: Citizenship Review, Ministry of Justice, 2008.

- For a more substantial discussion see, Hughes, Andrew S. and Alan Sears. “The Struggle for Citizenship Education in Canada: The Centre Cannot Hold.” In The Sage Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Democracy, edited by James Arthur, Ian Davies and Carole Hahn, 124-138. London: Sage, 2008.

- Reid, Alan, Judith Gill and Alan Sears. “The Forming of Citizens in a Globalized World.” In Globalization, the Nation-State and the Citizen: Dilemmas and Directions for Civics and Citizenship Education, edited by Alan Reid, Judith Gill and Alan Sears, 3-16. New York: Routledge, 2010, p. 9.

- For a fuller discussion see, Sears, Alan and Emery Hyslop-Margison. “Crisis as a Vehicle for Educational Reform: The Case of Citizenship Education.” Journal of Educational Thought 41, no. 1 (2007): 43-62.

- Levine, Peter. The Future of Democracy: Developing the Next Generations of American Citizens. Medford, MA: Tufts University Press, 2007. Levine, Peter. “Education for a Civil Society.” In Making Civics Count: Citizenship Education for a New Generation, edited by David E. Campbell, Meira Levinson and Frederick M. Hess, 37-56. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2012.

- Howe, Paul. Citizens Adrift: The Democratic Disengagement of Young Canadians. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010.

- Levine, “Education,” p. 38.

- There is an extensive literature but see, for example, Print, Murray. “Citizenship Education and Youth Participation in Democracy.” British Journal of Educational Studies 55, no. 3 (2007): 325-345. Kiwan, Dina. “Citizenship Education in England at the Crossroads? Four Models of Citizenship and Their Implications for Ethnic and Religious Diversity.” Oxford Review of Education 34, no. 1 (2008): 39-58. Kiwan, Dina. Education for Inclusive Citizenship. London and New York: Routledge, 2008. Council of Europe, “The European Year of Citizenship through Education” http://www.coe.int/T/E/ Cultural_Co-operation/education/E.D.C/Documents_and_publications/By_subject/ Year_2005/ (accessed February 9 2005).