Widespread concern about low rates of physical activity and high rates of obesity, depression, and anxiety among young people have drawn attention to the role schools play in fostering physical and mental health. This report by Bruce Ferguson and Keith Power examines the role of schools in promoting physical and mental health.

Widespread professional and public concern about low rates of physical activity and high rates of obesity, depression and anxiety among young people have drawn attention to the role schools play in fostering physical and mental health. The contributions that schools make to developing physical and mental health have become increasingly clear. Physical and health education have a long history in school systems but programs dealing explicitly with mental health are more recent. While they are now regarded as important dimensions of education, physical and mental health education and outcomes are not systematically assessed.

Current approaches to both physical health and mental health promotion in schools are driven by two separate influences. Historically, physical (health) education was thought to be a natural and harmonious complement to academic training. This view is reflected in modern times as a holistic approach to education with a focus on educating the “whole child.” A second influence derives from the life course approach to the epidemiology of chronic diseases including mental health problems. Based on the assumption that chronic diseases can be prevented by teaching students to adopt healthy lifestyles from an early age, the core concern of this latter framework is the cost to society of chronic disease. The framework also acknowledges health related quality of life issues and the cost and personal burden to individuals and families. Current approaches to school-based physical and mental health programming reflect concern for the optimization of life outcomes (i.e. quality of life) for students, but also function within the context of pressures to produce an economically competitive workforce and to reduce future health care costs. Our review of

the history and effectiveness of health education and promotion programs recognizes that physical and mental health promotion are inextricably linked.

Health curricula and physical education programs in schools are based on the belief that there are short-term physical, academic and psychological benefits

of providing students with health information and physical activity. It is also assumed that the establishment of a healthy lifestyle along with the capacity to make informed choices about health will be sustained into adulthood and reduce the incidence of chronic disease. Ontario’s Ministry of Education states that the vision of the health and physical education curriculum is that “the knowledge and skills acquired in the program will benefit students throughout their lives and help them to thrive in an ever-changing world by enabling them to acquire physical and health literacy and to develop the comprehension, capacity, and commitment needed to lead healthy, active lives and to promote healthy, active living” (The Ontario Curriculum Grades 1-8 Health and Physical Education 2010, pg. 3). While some of the short-term benefits have been demonstrated, the assumptions of adult benefits for good habits acquired early have not been demonstrated rigorously by the research. However, the field of life course epidemiology has many examples of how long-term risk for chronic disease is impacted by physical and social exposures during gestation, childhood, adolescence and young adulthood (Ben-Sholmo and Kuh, 2002; Hertzman, 1995). This evidence supports the long-term vision and goals of school-based health and physical education programs and provides impetus for longitudinal assessments of the programs that are now lacking.

… successful school-based mental health promotion holds the promise of reducing short and long-term distress to individuals and costs to society.

In the mid to late 1980’s the American Academy of Physical Education (Malina, 1987), the American Academy of Pediatrics Committees on Sport Medicine and School Health (1987), and the American College of Sports Medicine (1988) all called for school physical education to adopt health-related activity goals in response to the growing public health concerns related to physical inactivity. Before this period there had been little recognition of the role that schools

could play in enhancing students’ physical activity levels and subsequent health outcomes. However, during the 1990’s recognition of the global obesity epidemic began to emerge and increasingly public health groups called for schools to become engaged in promoting children’s physical activity to contribute to the prevention of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other non-communicable diseases associated with inactivity and obesity (Sallis, McKenzie, Beets, Beighle, Erwin, & Lee, 2012). Lipnowski & Leblanc (2012) reported that the prevalence of obesity has nearly tripled over the last 25 years, with up to 26% of young people (2 to 17 years of age) overweight or obese. Health consequences of childhood obesity include insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, poor self-esteem and a lower health- related quality of life. On a societal level, reducing chronic disease is an important economic issue in the context of spiraling health care costs. It has been estimated that 42% of Canada’s total direct health costs and over 65% of indirect costs are for chronic diseases. Thus the concerns both for the health of our children and escalating health care costs, have driven increased interest in school health and activity program as a way of preventing the long-term costs of chronic disease.

The goals of school-based mental health promotion and intervention programs have short- and long-term goals compatible with those of health promotion. In mental health the pathways to morbidity are very clear. Presence of a psychiatric diagnosis in childhood increases the odds of having a disorder in adolescence which in turn leads to increased odds of mental illness in adulthood (Investing in Mental Health, 2010). Therefore, prevention and early effective treatment has long-term payoffs for individuals and society. It is now known that the majority of mental health disorders emerge during childhood and adolescence. Estimates suggest that about 15 percent of young people have a mental disorder of some kind (Waddell et al., 2002), growing to as high as 25 percent in adulthood (Kessler et al., 2005). These disorders range from those that are highly prevalent but amenable to treatment (such as anxiety and depression) to those that are less common but extremely debilitating and persistent (such as autism and schizophrenia). The influence of mental disorders on individuals can be both immediate and far reaching. Each year, thousands of young people end their lives by suicide, making this the second leading cause of death following motor vehicle collisions in Canadian youth aged 10 to 24 years (Anderson & Smith, 2003; Statistics Canada, 2009). Despite the high prevalence of mental illness, including substance abuse disorders (albeit to a lesser degree), and its impact on the lives of children and families, most young people do not seek help or receive adequate timely access to evidence-based mental health services and supports (Offord et al., 1987). The Mental Health Commission of Canada (Investing in Mental Health, 2010) estimates that mental health problems gave rise to $50 billion in direct costs alone. Thus, given the clearly established pathways from childhood to adults mental disorders, successful school-based mental health promotion holds the promise of reducing short and long-term distress to individuals and costs to society.

Goals of school-based physical and mental health promotion programs

The health related competencies that students are expected to acquire change across their years at school. They begin with enjoyment of physical activity

and accumulation of knowledge about the importance of healthy eating and sleeping. By the end of secondary school students are expected to have developed appropriate personal fitness and physical skills as well as the knowledge, attitudes and commitment to lifelong healthy active living. With regard to mental health the goal is for students to be able to manage themselves and their relationships with others. This begins with age-appropriate self-regulation and cooperative interactive play in kindergarten. By the end of high school students should be able to be aware of and monitor their own internal psychological states, manage day-to-day stresses, be able to manage personal and school/work relationships and to be actively engaged in school/community. They are also expected to recognize emerging mental health issues in themselves and those around them as well as know when and how to seek help.

Both physical and mental health promotion are important from individual, social, and economic perspectives. Because of their centrality in the lives of children and youth, schools have been widely regarded as places for effective promotion and interventions in physical and mental health. We will examine how successful we have been to date.

The Greeks developed the physiocratic school of thought which acknowledged the connection between natural/social causes and healthy development. It

was understood that health and disease could not be dissociated from human behaviour or one’s physical and social surround (Tountas, 2009). Physical education reached a pinnacle in ancient Athens where individual excellence was the goal. The Athenians sought harmony of both the mind and body and thus physical education and training was held in high esteem and occupied a prominent place in most education programs. The object of physical education was not for the cultivation of physical development alone, but rather for the development of the overall individual (Mechikoff & Estes, 1993).

In the late 19th century, physical education was based on European approaches to what was termed “gymnastics.” These systems were often built around equipment and focused on strength and skills. In the early part of the 20th century, as school systems developed in North America, organized sports and games became a larger part of physical education (Siedentrop, 2001). During

the 1930’s physical education was played down but with the advent of World War II fitness became the focus behind a revival of physical education which emphasized the development of strength, endurance, coordination and the skills for military service. The measurement of these skills (e.g. strength, speed, agility, climbing, etc.) became a major part of physical education and in some areas remains so.

In the 1980’s, two lines of research had a broad impact on the development of the field of physical health promotion. The first was the work of epidemiologists revealing the rapidly rising rate of obesity in the North American population and the concomitant rise in prevalence of non-communicable chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes, and cancer. At the same time, evidence began accumulating to suggest that regular exercise (with emphasis on aerobic exercise) could help to control weight, reduce body fat, improve circulatory function, control blood-glucose levels, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce stress and depression (Blair, Kohl, & Powell, 1987). These two lines of evidence resulted in physical education’s transformation from a “fitness model’ to what has been labelled as “health-related physical education” (McKenzie and Sallis, 1996). The health benefits of physical activity have remained as an integral part of the argument for physical education into the present day. The thrust is to develop children’s knowledge, attitudes, and physical activity practices in the belief that they will lead to adult lifestyle choices that will enhance well-being and lower the risk of chronic disease (Baranowski et al., 1997). This model has had a profound influence on the comprehensive school health programs that are common today.

The whole school environment, including its individuals and their relationships, the physical and social environment and ethos, community connections and partnerships, and policies, are seen as important areas for action if a school is to promote health.

The development of the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (World Health Organization, 1986) provided the impetus for the development of the two most widely used school health promotion initiatives today, namely the Health Promoting Schools (HPS) and Comprehensive School Health (CSH) frameworks (St. Leger, Kolbe, Lee, McCall, & Young, 2007; Veugelers, & Schwartz, 2010). Although these frameworks differ in name, both frameworks address the broader school environment and have the same basic goals of advancing student health and achievement.

Health promoting schools (HPS)

The initial concept of the HPS framework evolved in Britain and Europe and was concerned with three main considerations:

- The specific time allotted to health related issues in the formal curriculum through subjects such as Biology, Home Economics, Physical Education, Social Education and Health Studies;

- The ‘hidden’ curriculum of the school including such features as staff/pupil relationships, school/community relationships, the school environment and the quality of services such as school meals;

- The health and caring services providing a health promotion role in the school through screening, prevention and child guidance (Young, 2005, p. 113).

Since 1986, the Health Promoting School concept has come to include empowering students by including them in the planning and decision-making processes. Currently, the World Health Organization (2014) defines a Health Promoting School as “…one that constantly strengthens its capacity as a healthy setting for living, learning, and working.” The whole school environment, including its individuals and their relationships, the physical and social environment and ethos, community connections and partnerships, and policies, are seen as important areas for action if a school is to promote health.

Comprehensive school health (CSH)

The CSH framework was first established in North America during roughly the same period as the HPS model. Similar to the HPS framework, the CSH movement originates from the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO, 1986) and addresses school health in a planned, integrated, and holistic way in order to support improvements in student achievement and wellbeing (Joint Consortium for School Health, 2014). Since its inception, the CSH framework has grown in popularity and has been implemented in more than 40 countries around the world (Veugelers & Schwartz, 2010).

The Joint Consortium for School Health (JCSH; 2014) has identified four pillars for CSH: 1) teaching and learning; 2) social and physical environments; 3) healthy school policy; and 4) partnerships and services. The teaching and learning pillar concentrates on the curricular and non-curricular education of students and the preparation and professional development of teachers in the areas of health. The goal is to provide age-appropriate knowledge and experiences that help students build the skills to improve their health and academic outcomes. The social and physical environment pillar is concerned with promoting health and mental health by supporting the development of quality relationships and the emotional well- being of students and staff, in addition to paying attention to how the physical context either promotes or hinders health development including safety, access to facilities and resources, and the quality of air and water. Healthy school policy refers to the management practices, decision-making processes, rules, procedures, and policies at all levels that influence health and affect the development of a respectful, welcoming, and caring school. The partnerships and services pillar is committed to building supportive working relationships within schools, between schools, and between schools and other community organizations.

Additional components of whole school health promotion initiatives

When Canadian schools implement health promotion initiatives modeled on

the JCSH framework, many of the program components address mental as well as physical health issues. For example, there is often a focus on positive school culture and positive learning environments, and concern for the quality of relationships within the school community. Life skills, such as stress management, are also included. There are components designed to prevent tobacco, alcohol, and drug use and to reduce other types of risky behaviours. Sex health education and healthy sexuality is addressed starting in elementary school and throughout high school (with parental permission, students may be permitted to opt out of these programs). The Public Health Agency of Canada (2008) set out guidelines for sexual health education in Canada. These guidelines recommend defining sexual health after the World Health Organization (2006) which defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality” and defines sexuality as “a central aspect of being human throughout life encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction.” The definition stipulates that “for sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.” (World Health Organization, 2006). As the paper on social and emotional learning discusses, self-awareness is a central skill leading to the development of an evolving self-identity which is important to mental health. One’s sexual identity is a core aspect of self and as critical to good mental health as sexual health is to good physical health. Recognizing the schools’ role in supporting this development, Ontario in 2012 amended the Education Act by passing the Accepting Schools Act. The preamble to the act asserts that “all students should feel safe at school and deserve a positive school climate that is inclusive and accepting, regardless of race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability.” Along with the many other attributes, the Act stipulates the right of students to feel safe and included regardless of their sexual identities.

Effectiveness of the HPS and CSH approaches on physical health

An overarching question is how well have the HPS and CSH frameworks been implemented? Stewart-Brown (2006) noted that there is a dearth of studies that have included all of the components of either framework in their methodology or evaluation. One approach to looking at how closely the models have been followed is to carry out curriculum policy analysis. Thomson and Robertson (2012) have done such an analysis across Canadian provinces and territories since all (except Quebec) have endorsed the JCSH framework. Thomson and Robertson (2012) concluded that the majority of provinces and territories across Canada do not have curriculum policies that are fully in-line with the CSH framework. Most absent were curriculum policies explicitly directed at the empowerment of children and at health literacy. Not one province or territory could claim such an empowerment stance, and only five provinces have integrated aspects of critical health literacy into their curriculum.

Health and well-being

Evidence for the effectiveness of HPS and CSH programs to enhance health outcomes remains scarce since few studies have examined initiatives that incorporate all or even multiple components of the proposed frameworks (Bassett- Gunter, 2012). However, when schools do use aspects of a whole-school health promoting approach positive outcomes have been reported. For instance, the Alberta Project Promoting Active Living and Healthy Eating Schools initiative (APPLE) has adopted a comprehensive approach and reported several beneficial outcomes. After two years of implementation students at APPLE schools were more physically active, had a lower likelihood of obesity, and consumed more fruits and vegetables and fewer calories than students from other schools across the province (Fung, Kuhle, Lu, Purcell, Schwartz, Storey, & Veugelers, 2012). HPS and CSH programs that are most effective in changing students’ health or health- related behaviours tend to be intensive, long-lasting and involve a multi-pronged approach that includes teaching about health, changes to the school environment, and creating partnerships with the wider community (Stewart-Brown, 2006).

Health promotion programs have been shown to be effective in increasing the duration of physical activity and the rates of vigorous activity as well as decreasing the duration of watching television (Stewart-Brown, 2006; Dobbins et al., 2013). In contrast, the results of medical outcomes such as pulse rate, blood pressure and BMI are not consistently positive (Dobbins et al., 2013; Klakk et al., 2014). Sexual education programs have been shown to reduce risky sexual behaviors in young people (Sexual Information and Education Council of Canada, 2009; Silva, 2002)

Academic achievement

Even when most components of the HPS or CSH models are implemented, studies rarely report educational outcomes (Rowling and Jeffries, 2006.) However,

the evidence does suggest a positive relationship between healthy school communities or individual components of the CSH and HPS frameworks and improved academic outcomes (Basch, 2011; Murray, Low, Hollis, Cross, & Davis, 2007). The authors of a recent review (Rasberry et al., 2011) that examined the association between school-based physical activity and academic achievement substantiated earlier findings. They reviewed 251 associations representing measures of academic performance, academic behaviour, and cognitive skills and attitudes indicating that slightly more than half (50.5%) of the associations were positive and less than two percent were negative. These results suggest that increased school physical activity is either positively associated with academic achievement or not associated. It also strongly suggests that dedicating extra time for physical activity in schools does not hinder academic achievement.

Summary of physical health promotion

Overall, despite a lengthy history and well-developed and disseminated multidimensional models for school-based health promotion, the evidence

for the sought-after academic and health outcomes is not as extensive as one would like. It is established that school-based programs can change health knowledge, eating choices, activity levels and are associated with improved academic achievement. However, there is no longitudinal evidence that these changes lead to healthy adult lifestyles that in turn lead to improved well-being and lower prevalence of chronic diseases. Nevertheless, there is enough positive evidence to pursue comprehensive models of health promoting schools. Stewart- Brown (2006) in a review of reviews, indicated that successful programs tend to be of longer duration and higher intensity and to involve the whole school community (students, teachers, staff and parents/communities). Successful programs are generally multifactorial, with curricular components, changes to school environment/culture, and training of the school-based program leaders. It is essential that programs be chosen and implemented based on solid research evidence and must be evaluated to ensure they are properly implemented and achieve the intended outcomes.

History of school-based mental health promotion and intervention

From the time of the early Greeks, physical education included elements of psychological development. Once school health curricula were developed, they usually included some coverage of mental illness and alcohol/substance abuse. However, it was with the emergence of health promoting schools/comprehensive school health that explicit mental health programs were developed. As had happened with comprehensive school health, school-based mental health soon evolved a “whole school and community” framework.

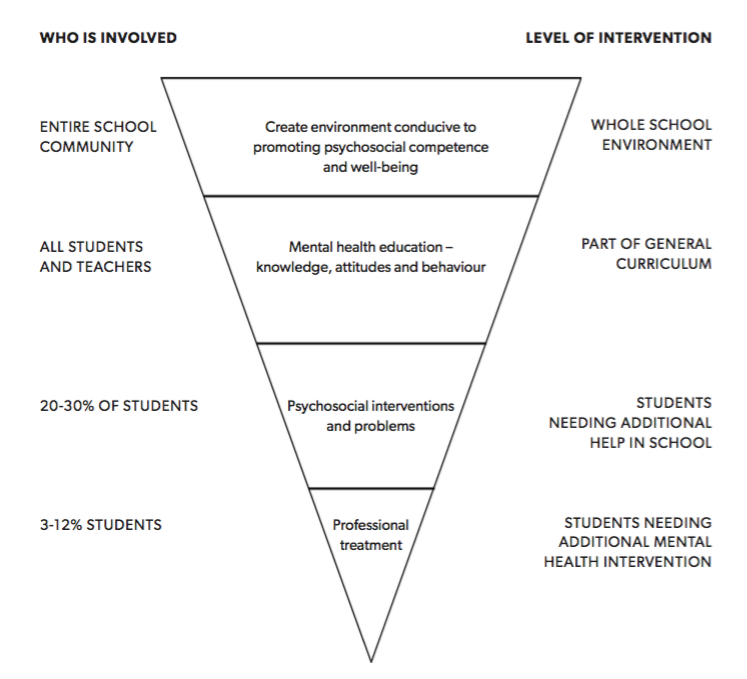

The dominant model for implementation of school-based mental health is represented by Figure 1 on the following page from Rowling and Weist (2004). The basis for school mental health is the need to shape the school organization to create an environment which is ‘health promoting’ for all members indicated in the first tier. This involves the quality of the relationships among teachers, parents and students and community agencies, a positive school ethos and the reinforcing role of school policies. The creation of safe and positive learning environments in all classrooms is another attribute (Weist, 2002). A second tier for action is the provision of curriculum designed to promote mental health and to reduce mental health problems. This includes mental health literacy and programs designed for destigmatising mental illness, dealing with bullying/ aggression, building resilience, and substance use prevention. The third tier acknowledges the need for school-based structures designed to identify and provide additional support for those students dealing with particular social, emotional, learning or mental health problems and mental disorders. The fourth tier focuses on the small percentage of students who require professional assessment and/or treatment for mental health problems by external health services or community agencies. In this work parents are often key partners and good collaboration and transition protocols are necessary to facilitate smooth pathways to care and back to the school. These final two tiers reflect the importance of schools, and especially teachers, as critical identifiers or “gatekeepers” in the early detection of children/adolescents who need specific support and/or professional care.

While this framework has been adopted around the world in varying forms (Rowling and Weist, 2004), it leaves open the decisions about which tiers will

be the focus for schools or school boards. The focus of this review falls on

the first two tiers: universal mental health promotion and specific or targeted programs. However, the essential components of child/youth mental health promotion are the fostering of self-regulation and social emotional skills. The age-appropriate development of these skills forms the foundation of mental health and, therefore, the key efforts of school-based mental health promotion will reside in the embedded instruction of these skills. Since self-regulation and social emotional skill development are covered in a companion paper, we will confine our review to initiatives aimed at improving mental health literacy and reducing stigma as well as specific intervention programs to increase resilience, and reduce /prevent bullying and aggression and alcohol/substance abuse.

Mental health literacy

A key way to develop commitment to mental health promotion in the whole school community is to provide mental health literacy training for educators, school staff, students and parents. Using literacy in this way is based on successful health promotion programs that have enhanced health literacy (Sanders et al., 2009). Mental health literacy is defined as “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management, or prevention” (Jorm et al., 1997). Thus literacy encompasses information about mental health problems and what we know about preventing and addressing them. In fact, Jorm (2012) has recently argued that increasing national mental health literacy in all segments of the population may hold promise for producing better population mental health.

The necessity for better educator literacy is emphasized by Wilson’s (2007) report that teachers or school counselors are the adults to whom adolescents were most likely to disclose mental health concerns. Short, Ferguson and Santor (2009) reported that the majority of educators interviewed expressed a high degree of concern about students’ mental health problems but admitted being poorly prepared to accurately identify or support students with problems. Also, Burns and Rapee (2006) have documented that many 15-17 year old are unable to recognize depression. Finally, the majority of students and 40% of parents indicate that embarrassment or stigma would keep them from seeing mental health professionals (Investing in Mental Health).

The goals for mental health literacy campaigns in school contexts are broad: (1) to better enable educators to identify, support and refer students needing help; (2) to increase knowledge and behaviours in teachers, students and parents about supporting good mental health and well-being; (3) to increase the willingness of students and parents to seek help for mental health issues; and (4) to decrease stigma towards individuals living with mental illnesses.

Rickwood and colleagues (2004) reported that in-school interactive presentations by people with lived experience of mental illness resulted in large self-reported increases in knowledge; moderate decreases in stigma but almost no impact on intention to seek help. Pinfold and colleagues (2005) showed that implementing a school-based mental health awareness program reduced stigma toward mental health problems and Naylor and colleagues (2009) reported similar results for a mental health teaching program for high school students.

Recently in Canada, a Mental Health & High School Curriculum Guide was created consisting of a teacher self-study module which provides basic information about mental health and the identification and linking of students experiencing mental health problems with health providers. In addition, it includes six modules for students that address the following domains of mental health: 1) stigma; 2) understanding mental health and mental illness; 3) specific mental disorders that onset during adolescence; 4) lived experiences of mental illness 5) help- seeking and support; and, 6) the importance of positive mental health. Kutcher and colleagues (2013) reported that this program was successful in raising the mental health literacy of students and teachers.

Although there is currently little empirical literature, the existing evidence suggests that programs can be mounted in schools that will achieve the goals for mental health literacy. It is critical that all programs delivered be evaluated for effectiveness.

Resilience programs

The capacity to cope with adversity and continue to function and develop well under difficult conditions is called resilience. Resilience is a key component of mental health and, therefore, is often considered an indicator of good mental health or well-being. Many school-based programs have been designed with the goal of increasing students’ strengths or protective factors as a way of increasing resilience. Recent reviews have focused on some strong programs which have shown favourable results on evaluation. For example, Brownlee and colleagues (2013) cite Barrett’s (2003) FRIENDS program as an example of a high quality program demonstrating successful outcomes. The program (described in Brownlee et al., 2013) teaches social and emotional skills to elementary and high school students and has resulted in increased self-esteem and hope for the future in elementary students as well as reduced symptoms of mood disorders in students at both elementary and secondary levels. However, no measures of resilience were used and the program focuses exclusively on the school context despite the fact that home and community social factors are important contributors to resilience, as pointed out by Ungar and colleagues (2014). However, there are other studies that underline the importance of relationships in the school context for increasing resilience and well-being (Ungar et al., 2014). In general, there is an over-reliance on academic achievement and school engagement as outcome measures but these measures may not be appropriate for many social and cultural groups. Brownlee and colleagues (2013) also acknowledge this measurement issue and list a number of specific resilience measurement tools which could be used in future research or assessment.

Programs to reduce/prevent bullying and aggression

Bullying and aggression are common psychosocial problems among children and reflect difficulties in forming and sustaining positive relationships (Pepler and Ferguson, 2013). These problems are so pervasive that in 2006 a Canadian network of researchers and community partners was formed to address the issues in a broad and proactive way. The focus of the network has been to promote relation- ships and prevent violence (www.prevnet.ca) by mobilizing knowledge, moving evidence-based practice into the community and advocating for policies which will reduce bullying and violence. The last few decades have seen a proliferation of an- ti-bullying and anti-violence programs in schools. Many of these programs have not been sustained and few have been evaluated. Our understanding of this phenome- non has been aided by research conducted by Cunningham and colleagues (2009). They examined teacher preferences for choosing bullying prevention programs and found that teachers preferred programs supported by the anecdotal reports of colleagues from other schools rather than those based on scientific evidence.

After reviewing different types of school-based mental health programs, Stewart-Brown (2006) noted that interventions to reduce aggression and violence were among the most effective. Many of these were modelled on the Olweus Bullying Prevention program (Olweus, 1993). Within this approach, it is considered essential to involve all members of the school community: teachers, school staff, students and parents. Smith and colleagues (2004) synthesized the literature on evaluation of whole-school anti-bullying programs. They found the largest effects for programs implemented in elementary or middle schools and for programs that included a process for monitoring the implementation to ensure that program guidelines were adhered to. Stewart-Brown (2006) noted that programs were most successful “ if developed and implemented using approaches common to the health promoting schools approach: involvement of the whole school, changes to the school psychosocial environment, personal skill development, involvement of parents and the wider community, and implementation over a long period of time” (pg. 16). Another school-based approach to preventing/reducing violence is the Roots of Empathy program (Gordon, 2005). Roots of Empathy is a theoretically derived universal prevention program that focuses on decreasing children’s aggression and facilitating the development of their social-emotional understanding and prosocial behaviors. The program is delivered by trained instructors and has as its cornerstone monthly visits by an infant and his/her parent(s) that serve as a springboard for lessons on emotional understanding, perspective taking, caring for others, and infant development. The program has been implemented in kindergarten to grade 8 classes across Canada and internationally. Two recent well-controlled studies have demonstrated positive effects on participants. A randomized study (Santos et al. 2011) indicated that the program decreased physical and indirect (relational) aggression and increased prosocial behaviours as rated by teachers. Student self-rating showed no differences. The improvements in teacher-rated aggression were maintained at a three year follow up while some of the gains in prosocial behaviours were lost. Schonert-Reichl and colleagues (2012) showed that the Roots of Empathy program delivered with a high degree of fidelity led to significant increases in peer-rated prosocial behaviours and decreases in teacher-rated proactive and relational aggression but not reactive aggression. These studies suggest that the Roots of Empathy program has potential for altering student behaviours in ways associated with better mental health and well-being.

Bullying and aggression remain pervasive problems for Canadians. Using school- based programs to address these issues makes sense as young people spend a good portion of their time in school and school is often a place where bullying and aggression are perpetrated. It is essential that schools adopt programs which are evidence-based and implement “whole school community” approaches with fidelity and monitoring. Meanwhile, intensifying our research efforts to find ways to reduce bullying and aggression should be a priority research area to improve overall well-being.

Substance abuse prevention

The rate of alcohol and drug use by Canadian youth raises concerns about the potential for substance abuse problems during adulthood. The association with mental health is clear since the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (2014) confirms pathways to substance abuse through accompanying mental disorders. As that paper notes, and was confirmed by the Mental Health Commission of Canada report, School-Based Mental Health in Canada: A Final Report (2013), most broad or school-based prevention programs have had negligible or even negative results. A recent review by Newton and colleagues (2011) acknowledges the past failures of school-based prevention programs but highlights the recent success of programs that select participants based on personality profiles (Conrod, 2013). The interventions incorporate psycho-educational, motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive-behavioural components, and include real life stories shared by high-risk youth in specifically-organised focus groups.

A novel component to this intervention approach is that all exercises discuss thoughts, emotions and behaviours in ways determined by the personality profiles. These interventions have led to reduced drinking, binge drinking and problem drinking symptoms in high-risk youth over a 6-month period.

Newton and colleagues (2011) also identify successful school-based universal prevention programs and isolate the characteristics of successful programs. These attributes are shown in Table 1.

Effective principles of school-based prevention for substance use |

| Evidence-based and theory driven |

| Acknowledge and target risk factors for substance use and psychopathology |

| Present developmentally appropriate information |

| Implemented before harmful patterns of use are established |

| Part of a comprehensive health education curriculum |

Adopt a social in uence or comprehensive approach to prevention and:

|

| Content is of immediate relevance to students |

| Use peer leadership, but retain teachers in a central role |

| Address values, attitudes and behaviours of the individual and community |

| Sensitive to cultural characteristics of target audience |

| Provide adequate initial coverage and continued follow-up booster sessions |

| Employ interactive teaching approaches |

| Can be delivered within an overall framework of harm minimization |

Reducing alcohol and substance abuse is an important part of reducing

risk behaviours and improving mental health in students. These recent demonstrations of effective programs are noteworthy and merit a knowledge mobilization effort to replace the many unproven programs currently used across Canada.

Measuring the outcomes of programs is a critical component both of establishing e ectiveness for programs and also of demonstrating that proven programs have been properly implemented in later practice.

Summary of mental health promotion programs

Overall, we have clear evidence that we can use school-based programs to increase knowledge and reduce the stigma attached to mental health problems. We can increase the knowledge and confidence of educators in dealing with students’ mental health issues. There are programs which reduce bullying/ aggression, improve resilience and prevent or reduce substance use. In general, effective programs are structured and delivered in ways similar to those in physical health promotion. Successful programs are multi-year, involve students, staff, families/communities and include curriculum, teaching of personal skills and changes in school environment/culture. It is also noted that universal mental health promotion programs are more effective than universal programs aimed at preventing specific mental disorders (Wells et al., 2003; Stewart-Brown, 2006). Thus it is clear that school-based mental health promotion works but that in practice we have to find ways to ensure schools select evidence-based programs and implement them with fidelity and monitoring of essential characteristics. It is also clear that we need to pay more attention to broad and consistent measures of both outcome and process.

Considerations for both physical and mental health promotion and prevention

For both physical and mental health promotion and prevention programs there are common issues in achieving successful outcomes. All reviews in both areas have noted the necessity of selecting programs that have been demonstrated to be effective (i.e. are evidence-based) and have been chosen for their applicability in the school’s particular context. A second issue relates to implementation. Full implementation of “whole of school community” as outlined in models is considered ideal for producing results and yet is rare. There are few studies that report on the fidelity to model achieved in an intervention program. This is related to another common issue:the narrowness of outcome measures. First, it is important to include process measures that allow assessment of the fidelity of implementation. Second, it is important to use multiple and appropriate outcome measures as has been suggested by Lee et al. (2005), Hussain et al. (2013) and Wells et al. (2003).

Measuring the outcomes of programs is a critical component both of establishing effectiveness for programs and also of demonstrating that proven programs have been properly implemented in later practice. An important consideration for

the many “whole school community” approaches to physical and mental health promotion is that reviews have noted that few studies have been carried out for programs that included all components of program models and studies often rely on a narrow set of outcome measures. However, as this review has indicated there are many programs which have demonstrated at least partial success. We will do a brief review of past measures and then consider what school systems should be measuring to ensure their goals are being realized.

Measures from past research

There has been debate in the literature about the utility of fitness testing in schools (Lloyd et al., 2010). Tremblay and colleagues (2010) used data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey to show that the fitness of Canadian children had declined since it was last measured in 1988. Although fitness testing is not a standard practice in Canadian schools, there are excellent standardised assessments available. One example is the Guidelines for Fitness Assessment in Manitoba Schools (2004). Other systems have been used internationally such as Eurofit (1983). These assessment batteries provide a rich resource for future studies to develop useful assessment tools as well as for school boards who have included physical fitness as a goal to assess their success in promoting physical health.

As the reviews have indicated, the evidence for the impact of comprehensive models of school health or health promoting schools has been varied but

show enough promise to recommend continued study (Stewart-Brown, 2004). Among the concerns raised by reviewers is the lack of a broad set of measures

to include indicators for all aspects of this comprehensive approach. Lee and colleagues (2005) have proposed a model for evaluating such programs. Apart from academic achievement and physical fitness/skills, most outcome measures (attitudes, lifestyles, risk behaviours, school ethos, self-efficacy) listed in this framework rely on student self-report with some observational measures suggested. Student self-reports can be augmented by parent report of diet and activity. While it would ideal to have multiple outcome measures from more

than one source, efficiency dictates that the assessment of these comprehensive models will continue to focus on student self-reports which in the past have been successful in showing effects for more targeted interventions.

The success of mental health literacy programs has been demonstrated by pre- post testing of mental health related knowledge in the case of both students and teachers (Rickwood et al., 2004; Hartman et al., 2013; Kutcher et al., 2013). Assessment of reductions in stigma have used established measures of social distance, self-stigma of seeking help and self-esteem (Hartman et al., 2013). The Opening Minds (2013) initiative of the Mental Health Commission of Can- ada developed two 11-item scales. The first measured stereotypic attributions (controllability of the illness, potential for recovery, and potential for violence and unpredictability) and the other measured behavioural intentions related to social acceptance (desire for social distance and feelings of social responsibility for mental health issues). Questions were worded to be accessible to a grade six reading level. This is an area where there is clearly a choice of useful measures from past studies that can be used in future research.

The research literature on bullying and aggression has used observation methods as well as student, peer, teacher, and parent report (Smith et al, 2004; Schonert- Reichl, 2012). The reviews of school-based programs to build resiliency ( Brownlee et al., 2013; Ungar et al., 2014) have noted that past research has often failed to measure the contextually correct behaviours and also that they have not taken advantage of well-constructed measures of resilience. Examples of such measures are the Youth Resiliency: Assessing Developmental Strengths (YR:ADS) (Donnen and Hammond, 2007) and the Child and Youth Resilience Measure CYRM-12) (Liebenberg et al., 2013). Both of these questionnaires are self-report measures and may be of broader interest given the close association of resilience to general mental health. Effective alcohol and substance use prevention programs have used selected sample (targeted prevention) and have tended to focus on self-report of specific substances (e.g. alcohol) and clinical symptoms (Conrod et al., 2013). These targeted intervention programs have developed measures which are suitable for evaluating future research in the areas but may have limited use at the school or system level.

There are many mental health measures for use with children and youth. For example, the Child and Youth Mental Health Service of the Anna Freud Centre compiled a compendium titled “Mental health Outcome Measures for Children and Young People (www.ana.freud.camhs.uk). This document reviews and characterizes a great many tools developed either for screening for specific or broad categories of mental health problems or for detecting change with treatment interventions. None are at all suited to the task of evaluating universal mental health or well-being promotion programs for schools which would need to assess feelings of well-being, quality of relationships with peers and adults, management of day-to-day stressors, risk behaviours, and engagement in home, school and community. Evaluating how systems are succeeding in promoting mental health at the school and school board levels will require different instruments than those used in past research.

What must be measured in the future?

A practical way to approach this question is to examine the goals or expectations education systems have set out for their health, physical education and personal development. As was noted above, the Comprehensive School Health model of health adopted in Canada has included many of the goals of mental health pro- motion programs. Over the past several years, many systems have adopted goals of promoting general well-being. Alberta has set out a Framework for Wellness Education (2009). The Ontario Ministry of Education launched a mental health initiative in 2011 (http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/parents/mentalHealth.html) and has recently released a new “vision” for education (Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario, 2014) which includes student well-be- ing as one of four explicit goals.

The Ontario Curriculum for Health and Physical Education (2010) sets out the following goals (pg. 3):

Students will develop:

- the living skills needed to develop resilience and a secure identity and sense of self, through opportunities to learn adaptive, management, and coping skills, to practice communication skills, to learn how to build relationships and interact positively with others, and to learn how to use critical and creative thinking processes;

- the skills and knowledge that will enable them to enjoy being active and healthy throughout their lives, through opportunities to participate regularly and safely in physical activity and to learn how to develop and improve their own personal fitness;

- the movement competence needed to participate in a range of physical activities, through opportunities to develop movement skills and to apply movement concepts and strategies in games, sports, dance, and other physical activities;

- an understanding of the factors that contribute to healthy development, a sense of personal responsibility for lifelong health, and an understanding of how living healthy, active lives is connected with the world around them and the health of others.

The Health and Life Skills Curriculum for Alberta (2002) similarly notes that (pg.3):

- Students will make responsible and informed choices to maintain health and to promote safety for self and others.

- Students will develop effective interpersonal skills that demonstrate responsibility, respect and caring in order to establish and maintain healthy interactions

The Alberta Physical Education Curriculum (2000) says that (pg. 2):“Physical education promotes personal responsibility for health and

fitness and for students to develop a desire to participate for life.”

As these curricular excerpts indicate, assessment of whether schools have met their provincially set mandates will require measurement of physical fitness and activity, social relationships with peers and adults, sense of well-being, sense of self-efficacy with regard to physical and mental health, and resilience, as well as some indications of how students regard their connection to school, family and community or culture. In addition, given the passage of the Accepting Schools Act (2012) in Ontario, schools need to assess student perceptions of safety and belonging. Accomplishing this will require measures that offer the capacity to assess a broad spectrum of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours across schools and school systems. There are some excellent candidate instruments available.

Health and mental health

The Early Development Instrument (Janus and Offord, 2007) assesses “school readiness” of populations of kindergarten/grade 1 students. It is a teacher completed scale that measures five domains: physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, communication and general knowledge. The measure is not intended as a screening or diagnostic tool for individual children, but rather to assess the school readiness of groups of children (Janus & Duku, 2007) and has been used to map the school readiness of children in communities across Canada (http:// earlylearning.ubc.ca/maps/edi/bc/). It is clearly an excellent broad spectrum measure for very young students.

The Middle Years Development Instrument (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2013) is a parallel instrument developed to measure well-being in grades 4 to 7. It is a student completed questionnaire that measures five domains: physical health and well-being, connectedness, social and emotional development, school experiences and use of afterschool time. The questionnaire covers many of the domains set out by education curricula as important goals (e.g. activity, health behaviours, self- development, relationships). It is designed to be a population-level tool and not for individual use. Thus, like the Early Development Instrument, the Middle Years Development Instrument is ideal for education system use.

Another measure that has potential but has not yet been used in evaluating school mental health initiatives is “Tell Them From Me” (www.thelearningbar.com) which has student and educator surveys. The student survey measures include bullying, social, institutional and intellectual engagement, risky behaviours, physical activity, emotional health, academic outcomes, school context, quality instruction, family context, and demographic factors. This measure covers many of the issues which school mental health programs attempt to impact which could make “Tell Them From Me” a valuable measure, or a template for developing measures, in future studies and assessments.

Finally, the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2004) noted that “relationships are the ‘active ingredients’ of the environment’s influence on healthy human development. They incorporate the qualities that best promote competence and well-being” (pg. 1). Thus, it is essential that priority be given to the accurate and reliable measurement of the age-appropriate state of children’s relationships with the adults that are central to their lives. The Middle Years Development Instrument includes assessments of connectedness to adults at school, home and in the community. “Tell Them From Me” assesses social relationships at school and the family context. Future evaluations must pay particular attention to mea- surement of these critical relationships!

Risk Behaviours

The Middle Years Development Instrument incorporates measures of bullying/ aggression as does “Tell Them From Me” which also measures other risk be- haviours. Perhaps the most relevant measure of tobacco, alcohol and drug use

at the system level is the Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS) from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The OSDUHS began as a drug use survey in 1977, but is now a broader survey of adolescent health and well-be- ing. Topics covered include tobacco, alcohol and other drug use and harmful consequences of use, mental health indicators, physical health indicators, health care utilization, body image, gambling and video gaming behaviours and problems, violence and bullying, criminal behaviours, school connectedness, and family life. At present, two reports have been developed from the 2013 data: Drug Use in Ontario Students 1977-2013 and Mental Health and Well-Being of Ontario Students 1991-2013. Given the evolution of the OSDUHS, it may be another excellent tool for developing future evaluations of comprehensive school physical and mental health programs. These instruments are examples of measures that could be used to monitor risk behaviours across schools and school boards.

The current state of our children’s physical and mental health has brought school based health promotion into the spotlight. Given the widespread concerns, comprehensive models for intervention have been developed

and described above. In no case is the evidence as clear and detailed as we would like. Reviewers have pointed to poor implementation of models and inadequate measures as potential explanations for the still ambiguous and incomplete results of past initiatives. These are problems of methodology that can be improved in future research. This will require the collaboration of policy-makers, educators and health and mental health researchers. In terms of promotion programs, the evidence supports moving forward assertively

to mount such programs in schools. The similarity of models for physical and mental health promotion in schools suggests potential for a deeper integration in a long-term whole of school approach with an investment in ongoing evaluation. There are excellent broad spectrum measures across the elementary and secondary school to assess such efforts. In planning such future programs, consideration should be given to an observation made by Stewart-Brown after reviewing school-based physical and mental health promotion programs. She observed “that mental health should be a feature of all school health promotion initiatives and that effective mental-health promotion is likely to reduce substance use and improve other aspects of health-related lifestyles that may be driven by emotional distress” (pg. 17).

The critical factors in the success of health promotion initiatives are to have school districts select evidence-based programs and implement them with fidelity—monitoring implementation and measuring outcomes will be critical

in this regard. In doing this, we are faced with changing how educators choose programs, implement them and evaluate them. While these changes will not be easily accomplished, achieving them is essential to improving the life outcomes of our children and youth. Moreover, the convergence of need and capacity in the developed world gives us an opportunity to improve the life outcomes of our children and youth who make up 25% of our population and 100% of our future.

- Alberta Curriculum Physical Education K-12. (2000). Retrieved September 2014 from http:// www.education.alberta.ca/media/450871/phys2000.pdf

- Alberta Curriculum Health and Life Skills Kindergarten to Grade 9. (2002). Retrieved September 2014 from http://education.alberta.ca/media/313382/health.pdf

- Alberta Curriculum Career and Life Management (Senior High). (2002). Retrieved September 2014 from https://education.alberta.ca/media/313385/calm.pdf

- Alberta Education. (2009). Framework for Wellness Education Kindergarten to Grade 12. Retrieved August 2014 from http://education.alberta.ca/media/1124068/framework_ kto12well.pdf

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committees on Sport Medicine and School Health. (1987). Physical fitness and the schools. Pediatrics, 80, 449-450.

- American College of Sports Medicine. (1988). Physical fitness in children and youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 20, 422-423.

- Anderson, R.N. & Smith, B.L. (2003). Deaths: Leading causes for 2001. National Vital Statistics Report, 52. 1-86.

- Baranowski, T., Bar-Or, O., Blair, S., Corbin, C., Dowda, M., Freedson, R., … & Ward, D. (1997). Guidelines for school and community programs to promote lifelong physical activity among young people. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 50(RR-6), 1-36.

- Basch, C. E. (2011). Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. Journal of School Health, 8(10), 650-662.

- Bassett-Gunter, R., Yessis, J., Manske, S., & Stockton, L. (2012). Healthy School Communities Concept Paper. Ottawa, Ontario: Physical and Health Education Canada. Retrieved from http://www.phecanada.ca/sites/default/files/healthy-school-communities-concept- paper-2012-08.pdf

- Ben-Shlomo, Y. & Kuh, D. (2002). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges, and international perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 285-2293.

- Blair, S., Kohl, H., & Powell, K. (1987). Physical activity, physical fitness, exercise, and the public’s health. The Academy Papers, 20, 53-69.

- Brownlee, K., Rawana, J., Franks, J., Harper, J. Bajwa, J., O’Brien, E., & Clarkson, A. (2013). A Systematic Review of Strengths and Resilience Outcome Literature Relevant to Children and Adolescents. Child and Adolescent Social Work, 30, 435–459.

- Burns, J. R.& Rapee, R. M. (2006). Adolescent mental health literacy: Young people’s knowledge of depression and help seeking. Journal of Adolescence, 29(2), 225–239.

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2014). Child and Adolescent Pathways to Substance Use Disorders. Retrieved from http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-Child- Adolescent-Substance-Use-Disorders-Report-2014-en.pdf July 2014. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online January 23, 2013. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.651

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (2013) Drug Use in Ontario students 1977- 2013. Retrieved August 2014 from http://www.camh.ca/en/research/news_and_ publications/ontario-student-drug-use-and-health-survey/Documents/2013%20 OSDUHS%20Docs/2013OSDUHS_Detailed_DrugUseReport.pdf

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2013). Mental Health and Well-being of Ontario Students 1991-2013. Retrieved August 2014 from http://www.camh.ca/en/ research/news_and_publications/ontario-student-drug-use-and-health-survey/ Documents/2013%20OSDUHS%20Docs/2013OSDUHS_Detailed_MentalHealthReport. pdf

- Conrod, P., O’Leary-Barrett M., Newton, N., Topper, L., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Mackie, C., & Girard, A. (2013). Effectiveness of a Selective, Personality-Targeted Prevention Program for Adolescent Alcohol Use and Misuse. JAMA Psychiatry , Published online January 23, 2013. www.JAMAPSYCH.com

- Cunningham, C. E., & Vaillancourt, T., Rimas, H., Deal, K., Cunningham, L., Short, K. & Chen, Y. (2009). Modeling the Bullying Prevention Program Preferences of Educators. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, DOI 10.1007/s10802-009-9324-2Sconline: May, 2009.

- Dobbins, M., Husson, H., DeCorby, K., & LaRocca, R. L. (2013). School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 2.

- Donnon, T., & Hammond, W. (2007a). A psychometric assessment of the self-reported youth resiliency: Assessing Developmental Strengths questionnaire. Psychological Reports, 100, 963-978.

- Eurofit. (1983). Testing Physical Fitness Experimental Battery. Retrieved August 2014 from http://www.bitworksengineering.co.uk/Products_files/eurofit%20 provisional%20handbook%20leger%20beep%20test%201983.pdf

- Fung, C., Kuhle, S., Lu, C., Purcell, M., Schwartz, M., Storey, K., & Veugelers, P. J. (2012). From “best practice” to “next practice”: The effectiveness of school-based health promotion in improving healthy eating and physical activity and preventing childhood obesity. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activty, 9(1), 27.

- Gordon, M. (2005). Roots of Empathy: Changing the world child by child. Toronto, ON: Thomas Allen.

- Hartman, L., Michel, N., Winter, A., Young, R., Flett, G., & Goldberg, J. (2013). Self-stigma of mental illness in high school youth. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28, 28-42. Hertzman, C, (1995). The biological embedding of early experience and its effects on health in adulthood. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 85-95.

- Hussain, A., Christou, G., Reid, M., & Fremman, J. (2013). Development of core indicators and measures (CIM) framework for school health and student achievement in Canada. Summerside, PE: Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health.

- Janus, M. & Offord, D. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Early Development Instrument (EDI): A teacher-completed measure of children’s readiness to learn at school entry. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 39(1), 1-22.

- Janus, M. & Duku, E. (2007). The School Entry Gap: Socioeconomic, Family, and Health Factors Associated With Children’s School Readiness to Learn. Early Education and Development 18(3), 375-403.

- Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. The Medical Journal of Australia, 166(4), 182-186.

- Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67(3), 231-243.

- Kessler, R.C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K.R., & Walters, E.E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602.

- Klakk, H., Andersen, L. B., Heidemann, M., Møller, N. C., & Wedderkopp, N. (2014). Six physical education lessons a week can reduce cardiovascular risk in school children aged 6–13 years: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 42(2), 128-136.

- Kutcher,K. , Wei, Y. , McLuckie, A. & , H.Bullock. (2013). Educator mental health literacy: A programme evaluation of the teacher training education on the mental health & high school curriculum guide, Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. Retrieved August 2014 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2013.784615

- Lee, A., Cheng, F. K., & St Leger, L. (2005). Evaluating health promoting schools in Hong Kong: Development of a framework. Health Promotion International, 20, 177-186.

- Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M. & LeBlanc, J. (2013). The CYRM-12: A brief measure of resilience. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 104, 131-135.

- Lipnowski, S. & LeBlanc, C. (2012). Canadian Paediatric Society Healthy Active Living and Sports Medicine Committee. Paediatric Child Health, 17(4), 209-10.

- Malina, R. N. (1987). President’s message. The AAPE News, 8, 1-2.

- Manitoba Ministry of Education. (2004). Guidelines for Fitness Assessment in Manitoba Schools. Retrieved August 2014 from http://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/cur/physhlth/guidelines/fit_assess.pdf

- McKenzie, T., & Sallis, J. (1996). Physical activity, fitness, and health related physical education. In S. Silverman & C. Ennis (Eds.), Student learning in physical education: Applying research to enhance learning (pp.223-246). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Mechikoff, R., & Estes, S. (1993). A history and philosophy of sport and physical education. Madison, Wisconsin: Brown and Benchmark.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2010). Making the Case for Investing in Mental Health in Canada. Retrieved from <http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/ system/files/private/document/Investing_in_Mental_Health_FINAL_Version_ENG.pdf

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2013). School-based Mental Health in Canada: A Final Report. Retrieved July 2014 from http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/ node/14036

- Mirolla, M. (2004). The Cost of Chronic Disease in Canada. Ottawa: Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada. Retrieved August 2014 www.gpiatlantic.org/pdf/ health/chroniccanada.pdf

- Murray, N. G., Low, B. J., Hollis, C., Cross, A. W., & Davis, S. M. (2007). Coordinated school health programs and academic achievement: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of School Health, 77(9), 589-600.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2004). Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships: Working Paper No. 1. Retrieved August 2014 from www. developingchild.harvard.edu

- Naylor, P. B., Cowie, H. A., Walters, S. J., Talamelli, L., & Dawkins, J. (2009). Impact of a mental health teaching programme on adolescents. The British Journal of Psychiatry, The Journal of Mental Science, 194(4), 365-370.

- Newton, N.C., O’Leary-Barrett, M., & Conrod, P. (2013). Adolescent substance misuse: Neurobiology and evidence-based interventions. Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience, 164,685-708.

- Offord, D.R., Boyle, M.H., Szatmari, P., Rae-Grant, N.I., Links, P.S., Cadman, D.T., Byles, J.A., Crawford, J.W., Munroe Blum, H., Byrne, C., Thomas, H. and Woodward, C.A. (1987). Ontario Child Health Study: II. Six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 832-836.

- Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell.

- Ontario Curriculum Grades 1-8 Health and Physical Education. (2010). Retrieved August 2014 from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/healthcurr18.pdf

- Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario. Retrieved August 2014 from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/about/ renewedVision.pdf

- Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.jcsh- cces.ca/index.php/about

- Pepler, D. & Ferguson, H.B. (Eds). (2013). A focus on relationships. In Pepler, D., & Ferguson, H.B. Understanding and addressing girls’ aggressive behaviour problems: A focus on relationships. Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier University Press.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2008) Canadian Guidelines for Sexual Health Education. Retrieved from http:// in October, 22014

- Rasberry, C. N., Lee, S. M., Robin, L., Laris, B. A., Russell, L. A., Coyle, K. K., & Nihiser, A. J. (2011). The association between school-based physical activity, including physical education, and academic performance: A systematic review of the literature. Preventive Medicine, 52, S10-S20.

- Rickwood, D., Cavanagh, S., Curtis, L. & Sakrouge, R. (2004). Educating Young People about Mental Health and Mental Illness: Evaluating a School-Based Programme. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 6(4), 23-32.

- Rowling, L. & Weist, M. D. (2004). Promoting the Growth, Improvement and Sustainability of School Mental Health Programs Worldwide. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 6(2), 3-11.

- Rowling, L., & Jeffreys, V. (2006). Capturing complexity: integrating health and education research to inform health-promoting schools policy and practice. Health Education Research, 21(5), 705-718.

- Sanders, L.M., Shaw, J.S., Guez, Z., Baur, C., & Rudd, R. (2009). Health literacy and child health promotion: Implications for research, clinical care, and public policy. Pediatrics, 124(Suppl 3), S306-S320.

- Santor, D., Short, K., & Ferguson, B. (2009). Taking mental health to school: A policy-oriented paper on school-based mental health for Ontario. Policy paper for the Ontario Centre of Excellence in Child and youth Mental Health. Retrieved from http://www.excellence- forchildandyouth.ca/sites/default/files/position_sbmh.pdf

- Sexual Information and education Council of Canada. (2009). Sexual health education in schools: Questions and answers (3rd edition) Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality,18, 47-60.

- Short, K., Ferguson, B. & Santor, D. (2009). Scanning the practice landscape in school-based mental health. Policy paper for the Ontario Centre of Excellence in Child and youth Mental Health. Retrieved July 2014 from http://www.excellenceforchildandyouth.ca/ sites/default/files/position_sbmh_practice_scan.pdf

- Smith, J. D., Schneider, B. H., Smith, P.K. & Ananiadou, K. (2004). The effectiveness of whole- school bullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. School Psychology Review 33, 547-560.

- Siedentop, D. (2001). Introduction to physical education, fitness, and sport (4th ed.). Toronto: Mayfield Publishing Company.

- Silva, M. (2002). The effectiveness of school-based sex education programs in promoting abstinence: A meta-analysis. Health Education Research, 17 (4), 471-481.

- Sallis, J. F., McKenzie, T. L., Kolody, B., Lewis, M., Marshall, S., & Rosengard P. (1999). Effects of health-related physical education on academic achievement: Project SPARK. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 70(2), 127-34.

- Sallis, J. F., McKenzie, T. L., Beets, M. W., Beighle, A., Erwin, H., & Lee, S. (2012). Physical education’s role in public health: Steps forward and backward over 20 years and HOPE for the future. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 83(2), 125-135.

- Santos, R., Chartier,, M., Whalen, J., Chateau, D. & Boyd, L. (2011). Effectiveness of violence prevention for children and youth. Healthcare Quarterly, 14 Special Issue.

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Smith, V., Zaidman-Zai, A. & Hertzman, C. (2012). Promoting Children’s Prosocial Behaviours in School: Impact of the “Roots of Empathy” Program on the Social and Emotional Competence of School-Aged Children. School Mental Health, 4 1-21.

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A. Guhn, M., Gaderman, A. M., Hymel, S., Sweiss, L. & Hertzman, C. (2013). Development and Validation of the Middle Years Development Instrument (MDI): Assessing Children’s Well-Being and Assets across Multiple Contexts. Social Indicators Research, 114, 345–369.

- Stewart-Brown, S. (2006). What is the evidence on school health promotion in improving health or preventing disease and, specifically, what is the effectiveness of the health promoting schools approach? Copenhagen: WHO.

- St. Leger, L. S., Kolbe, L., Lee, A., McCall, D. S., & Young, I. M. (2007). School health promotion. In Global perspectives on health promotion effectiveness (pp. 107-124). New York: Springer.

- The Learning Bar Inc. (2009). Tell Them From Me. Retrieved August 2014 from http://www. thelearningbar.com/surveys/effective-schools-student-survey/

- Thomson, D. C., & Robertson, L. (2012). Health curriculum policy analysis as a catalyst for educational change in Canada. Journal of Education and Learning, 1(1), 129-144.

- Tountas, Y. (2009). The historical origins of the basic concepts of health promotion and education: The role of ancient Greek philosophy and medicine. Health Promotion International, 24(2), 185-192. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap006

- Tremblay, M., Shields, M., Laviolette, M., Craig, C., Janssen, I.& Gorber, S. (2010). Fitness of Canadian children and youth: Results from the 2007-2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Statistics Canada Health Reports. Retrieved August 2014 from http://www. statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-003-x/2010001/article/11065-eng.pdf

- Ungar, M., Russell, P. & Connelly, G. (2014). School-Based Interventions to Enhance the Resilience of Students. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 4(1).

- Veugelers, P. J., & Schwartz, M. E. (2010). Comprehensive school health in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101, S5-8.

- Waddell,C., Offord, D.R., Shepherd, C., Hua, J., McEwan, K. (2002). Child psychiatric epidemiology and Canadian public policy-making: The state of the science and the art of the possible. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 825-832.

- Weist, M. D. (2002). Challenges and opportunities in moving toward a public health approach in school mental health. Journal of School Psychology, 353, 1–7.

- Wells, J., Barlow, & J., Stewart-Brown, S. (2003). A systematic review of universal approaches to mental health promotion in schools. Health Education, 103 (4), 197–220.

- Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? The Medical Journal of Australia, 187, Supplement S35-S39.

- World Health Organization. (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Ottawa, Canada.

- World Health Organization. (2006) Sexual Health Definitions (these definitions do not represent an official WHO position). Retrieved from www.who.int/reproductive-health/ gender/sexualhealth.html in October, 2014.

- World Health Organization. (2014). What is a health promoting school? Retrieved from http://www.who.int/school_youth_health/gshi/hps/en/ in August, 2014.

People for Education – working with experts from across Canada – is leading a multi-year project to broaden the Canadian definition of school success by expanding the indicators we use to measure schools’ progress in a number of vital areas.

The domain papers were produced under the expert guidance of Charles Ungerleider and Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group.

Author

Bruce Ferguson

Sickkids and the University of Toronto

Keith Power

Memorial University of Newfoundland

The Measuring What Matters reports and papers were developed in partnership with lead authors of each domain paper. Permission to photocopy or otherwise reproduce copyrighted material published in this paper should be submitted to Dr. Bruce Ferguson at [email protected] or People for Education at [email protected].

Document citation

This report should be cited in the following manner:

Ferguson, B. and Power, K. (2014). Broader Measures of Success: Physical and Mental Health in Schools. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

We are immensely grateful for the support of all our partners and supporters, who make this work possible.

Annie Kidder, Executive Director, People for Education

David Cameron, Research Director, People for Education

Charles Ungerleider, Professor Emeritus, Educational Studies, The University of British Columbia and Director of Research, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Lindy Amato, Director, Professional A airs, Ontario Teachers’ Federation

Nina Bascia, Professor and Director, Collaborative Educational Policy Program, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Ruth Baumann, Partner, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group

Kathy Bickmore, Professor, Curriculum, Teaching and Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Michelle Boucher, University of Ottawa, Advisors in French-language education and Ron Canuel, President & CEO, Canadian Education Association

Ruth Childs, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto

Jean Clinton, Associate Clinical Professor, McMaster University, Dept of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences

Gerry Connelly, Director, Policy and Knowledge Mobilization, The Learning Partnership

J.C. Couture, Associate Coordinator, Research, Alberta Teachers’ Association

Fiona Deller, Executive Director, Policy and Partnerships, Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario

Kadriye Ercikan, Professor, Measurement, Evaluation and Research Methodology, University of British Columbia

Bruce Ferguson, Professor of Psychiatry, Psychology, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto; Community Health Systems Research Group, SickKids

Joseph Flessa, Associate Professor, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Joan M. Green, O.Ont., Founding Chief Executive O cer of EQAO, International Education Consultant