Findings from People for Education’s latest report show that while most extracurricular activities and broader learning opportunities in Ontario schools have resumed since being paused during the pandemic, students’ access varies substantially depending on where they live.

Inequities persist: Extracurriculars, clubs, activities, and fundraising in Ontario’s publicly funded schools

Learning opportunities in schools that extend beyond the curriculum and include a broad range of activities such as sports, music, field trips, plays, and clubs are an essential part of a quality education. Participation in these kinds of activities is associated with improved mental health and well-being, academic success, and the development of vital skills and competencies that can benefit students well into their adult lives.1However, do all students have equal access to these learning opportunities?

In People for Education’s 2022-2023 Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS), 1,044 principals across all 72 publicly funded school boards in the province responded to questions on learning opportunities available at their schools. Principals were asked about each school’s availability of activities such as breakfast programs or learning an instrument during school hours, extracurricular clubs such as student leadership groups or 2SLGBTQ+ alliances, and opportunities such as participation in educational field trips and organized sports.

Findings show that while most extracurricular activities and learning opportunities have resumed since being paused due to the pandemic, students’ access varies substantially depending on geography as well as the median family income of the school neighbourhood. An analysis of these results also revealed that while fundraising supports many of these activities, it has not returned to pre-pandemic levels and varies widely depending on socioeconomic characteristics like household income.

Quick Facts

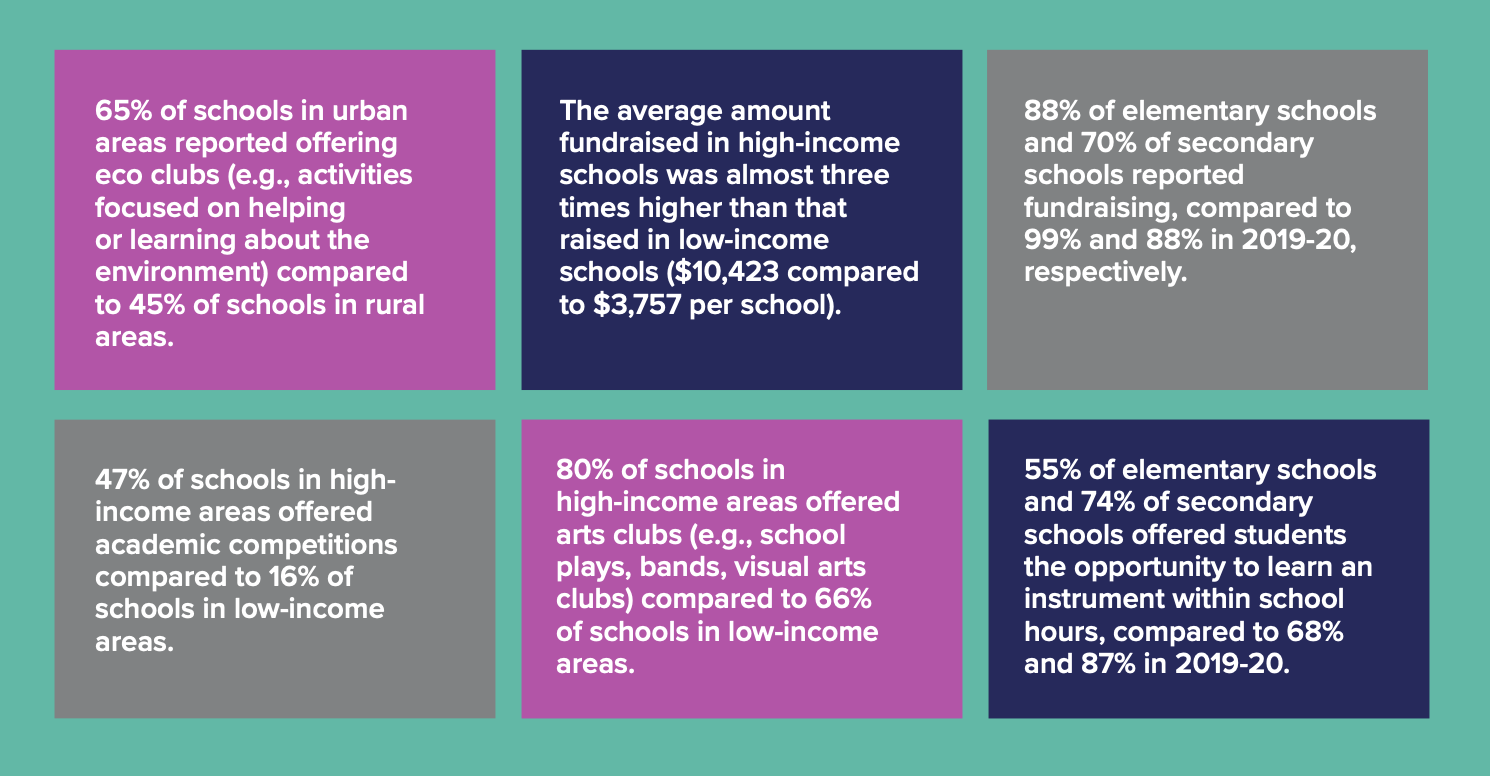

Survey responses revealed that the availability of extracurricular activities and learning opportunities depends on the median family income of the school neighbourhood and whether the school is located in an urban or rural area.i Schools in high-income areas are more likely to offer all extracurricular clubs (e.g., activities related to student leadership, social justice, environment, etc.) and all other school activities compared to schools in low-income areas, with the exception of breakfast/nutrition programs.

Some of the biggest differences are found in the proportion of schools offering “eco clubs”ii (71% in high-income areas compared to 43% in low-income areas) and academic competitions (47% in high-income areas compared to 16% in low-income areas). These findings support a recent research study in Quebec that found that schools with a socioeconomically advantaged student population (i.e., two employed parents and mothers who had completed high school) were more likely to offer extracurricular activities and special interest clubs than schools with a socioeconomically disadvantaged student population.2

Proportion of Ontario schools offering clubs, by neighbourhood income

Figure 1. Proportion of Ontario schools offering clubs, by median income of school neighbourhood

Source: People for Education’s 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

i Please see the Methodology section for more details on the classification of urban and rural areas.

ii Student groups and/or activities related to the environment, climate change/action, etc.

The only school activity reported by greater proportions of schools in low-income areas was breakfast or nutrition programs, which includes the provision of meal gift cards (96%, compared to 53% for schools in high-income areas).

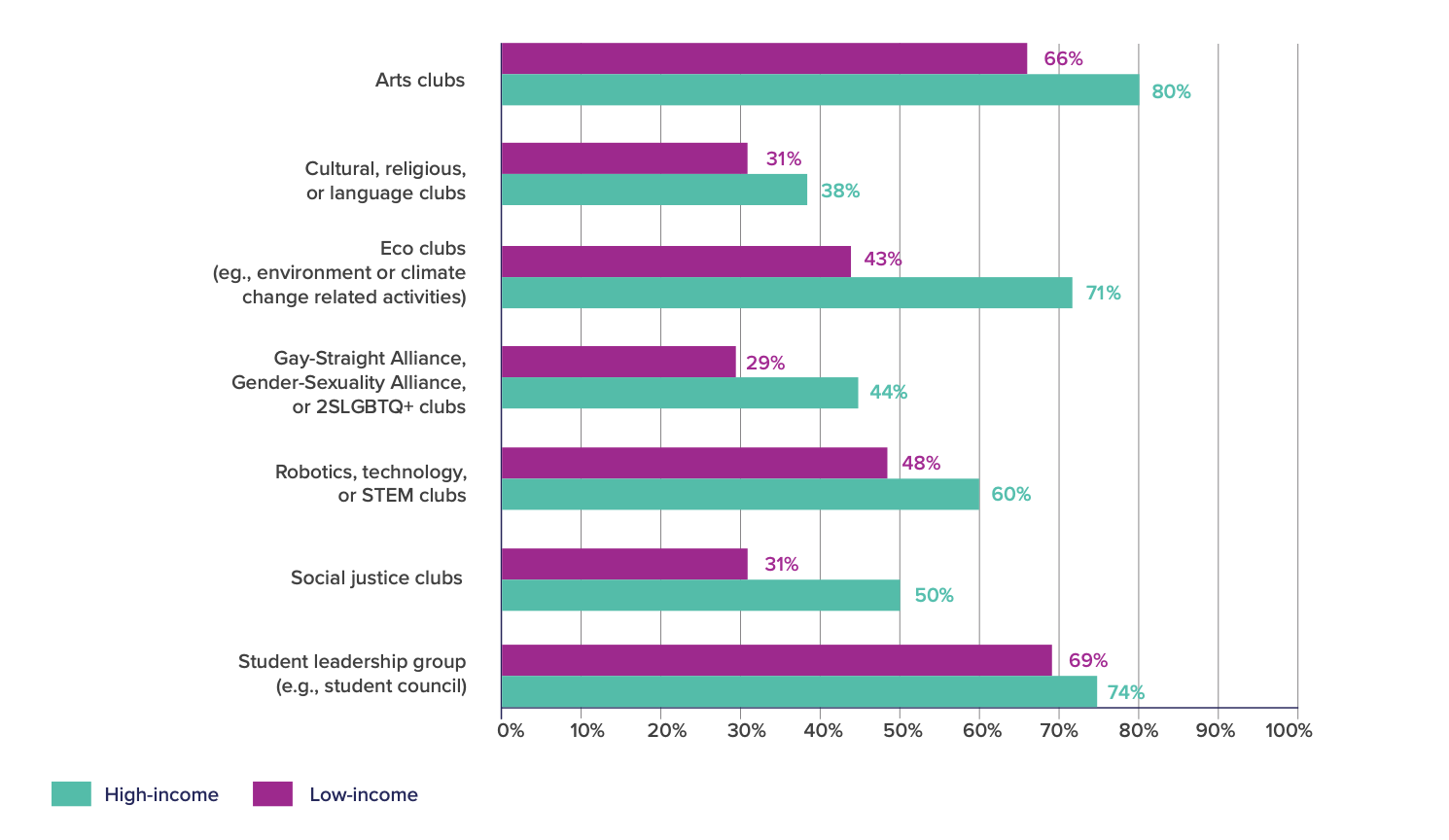

Proportion of Ontario schools offering activities, by neighbourhood income

Figure 2.Types of activities offered in Ontario schools, by median neighbourhood income

Figure 2.Types of activities offered in Ontario schools, by median neighbourhood income

Source: People for Education’s 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

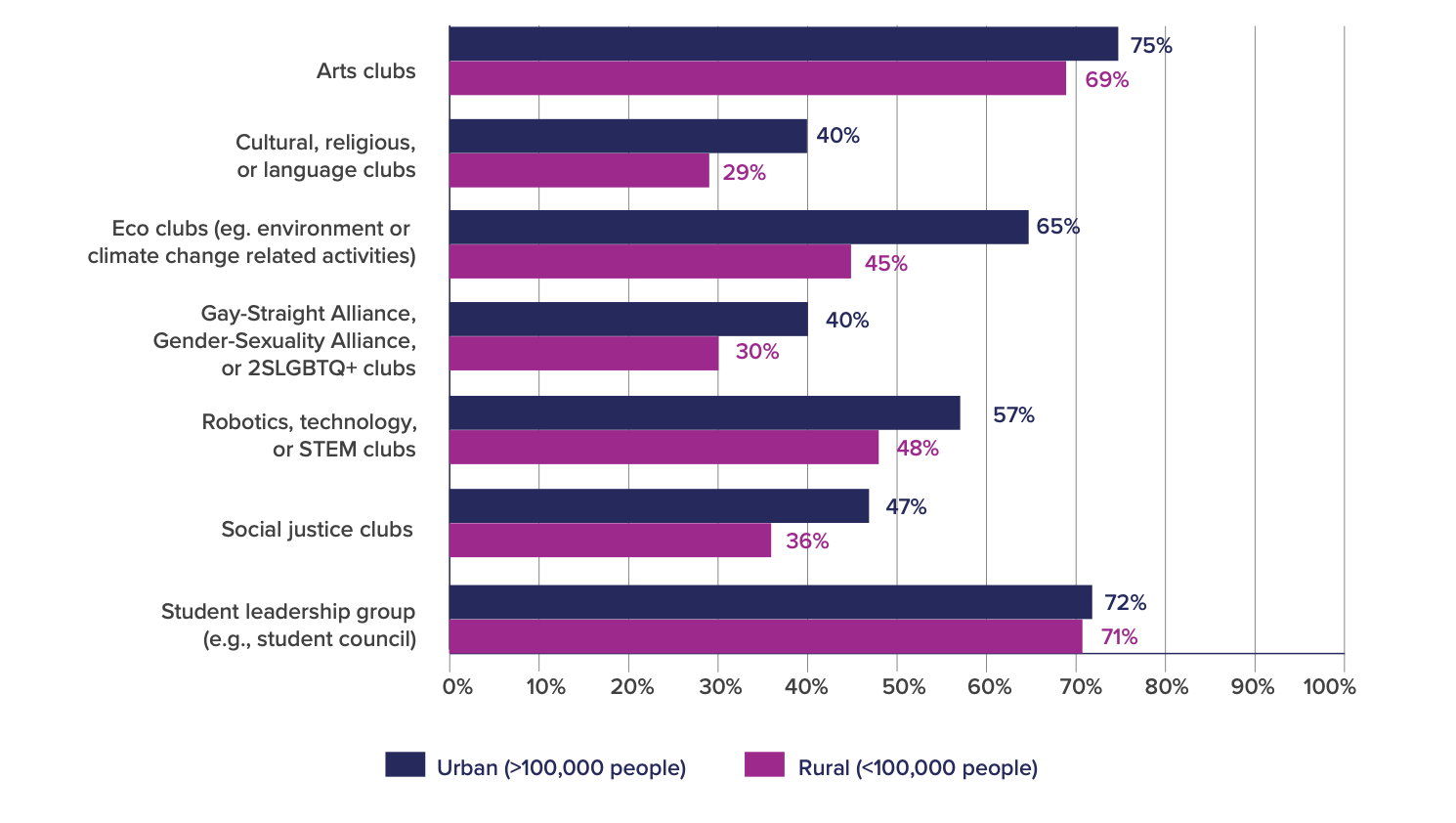

Geography also played a significant role in students’ access to clubs. Schools located in urban areas were more likely to report that they offer all school clubs compared to schools located in rural areas. Principals of rural schools reported lack of transportation as a barrier limiting their students’ access to extracurricular activities.

“Challenge: we are located in one small community but serve six small communities plus points in between. After-school transportation is not available and limits after school activities.”

Secondary school principal, Northern Ontario

The combination of rising fuel costs, irregular schedules, sparse benefits, and low pay has resulted in school bus driver shortages not only in rural areas, but in many regions across Ontario as well as the rest of Canada.3

Proportion of Ontario schools offerring clubs, by population size

Figure 3.Proportion of Ontario schools offering various clubs, by population size

Source: People for Education’s 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

“An increasing number of families are asking for support. Some students still have no access to computers in the evening and the school does not have the budget to purchase computers for all students. An increasing number of students are requesting financial support to participate in extracurricular activities as well.”

Secondary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

Over the last decade, fundraising has come to play an essential role in covering the costs of things like arts enrichment, charitable causes, sports equipment, school nutrition programs, and field trips. Because the costs for these activities must come from school budgets, rather than any provincial funding, many schools now rely on fundraising to augment their budgets.

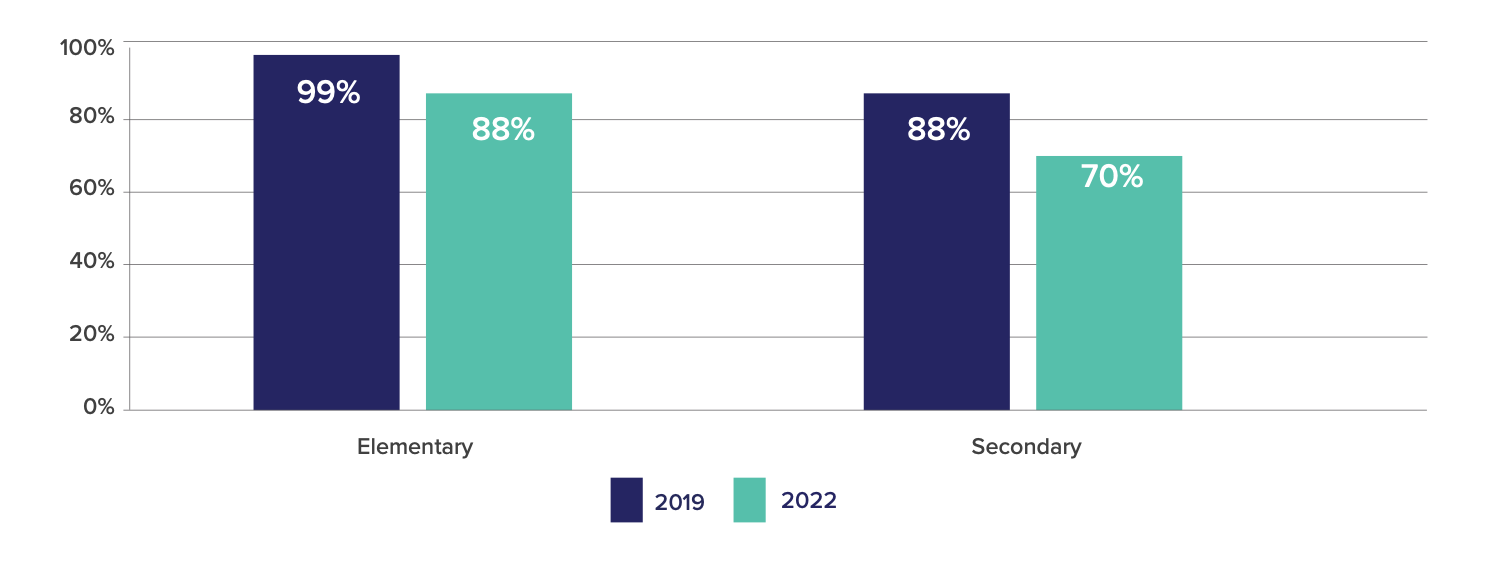

Fundraising in schools was notably lower in 2022-23 compared to the last school year before the pandemic. For elementary schools, 88% reported fundraising in 2022-23, compared to 99% in 2019-20. For secondary schools, 70% reported fundraising in 2022-23, down from 88% in 2019- 20.

Change in proportion of schools reporting fundraising, pre- and post-pandemic

Figure 4: Proportion of Ontario elementary and secondary schools reporting fundraising, 2019 and 2022

Source: People for Education’s 2019-20 and 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

Many principals attributed this decrease in fundraising activities to the challenges of pandemic recovery, as well as the increasing unemployment and financial hardship of many families and school communities.

“We have a small school with a lower socio-economic make-up. We know many of our families struggled to make ends meet during COVID—many lost their income. We tried not to pressure parents for fundraising this year.”

Elementary school principal, Greater Toronto Area

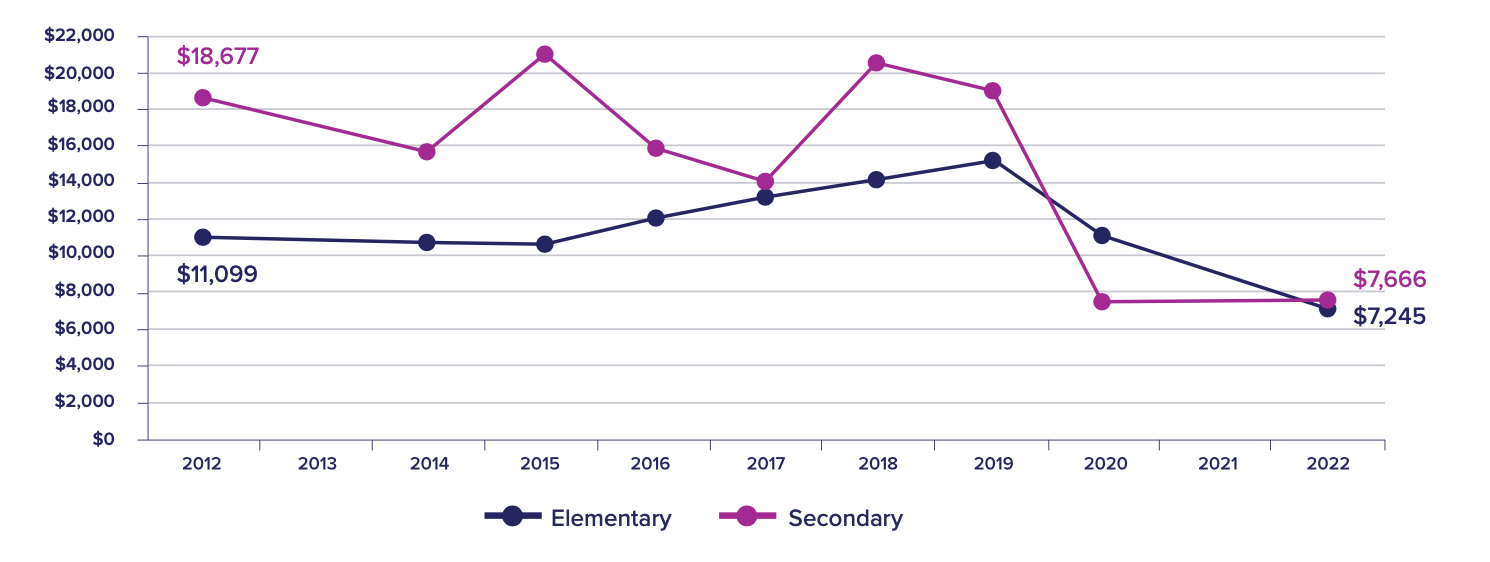

Over the past 10 years, the average amount fundraised per school in both elementary and secondary schools was lowest in 2022-23. Elementary schools raised an average of $7,245 while secondary schools raised an average of $7,666, compared to $11,099 and $18,677 in 2012-13, respectively. The average amount raised in high-income schools was almost three times higher than that raised in low-income schools in 2022-23 ($10,423 compared to $3,757 per school).

While schools have historically relied on fundraising to support extracurricular and school activities, many principals expressed sensitivity to the financial hardships being experienced by numerous families and communities.

“We did not fundraise the last two years due to COVID-19. Most of my families are financially challenged and I feel that fundraising poses undue stress on these families because they feel obligated to participate by purchasing items, even though they are not required to do so.”

Elementary school principal, Northern Ontario

With post-pandemic inflation and rising food insecurity among the general population, many schools reported a rise in immediate need for the school to help students and families with necessities such as food and classroom materials.

Average amount fundraised in Ontario elementary and secondary schools, change over time

Figure 5: Average amount fundraised in Ontario elementary and secondary schools, 2012-2022

Source: People for Education’s 2012-13, 2014-15, 2015-16, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018-19, 2019-20, fall 2020, 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

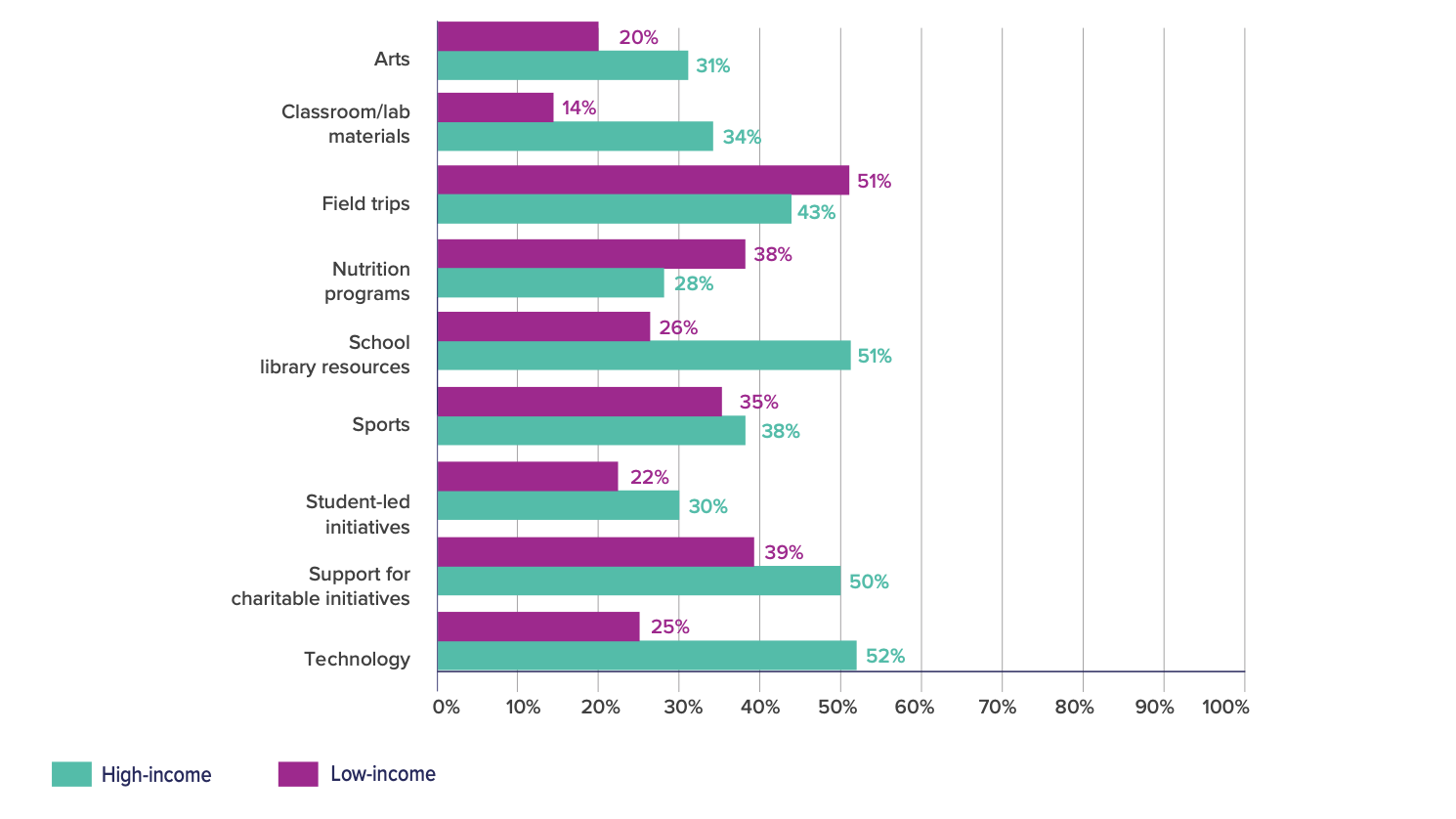

An analysis of what schools fundraise for, organized by whether a school is in a high-income or low-income neighbourhood, revealed key differences. While schools in high-income neighbourhoods were more likely to use fundraising money for technology, library resources, and classroom/lab materials, schools in low-income neighbourhoods were more likely to use those funds for nutrition programs and field trips.

Differences in fundraising initiatives in high- vs low-income schools

Figure 6: What Ontario schools fundraise for, by median neighbourhood income

Source: People for Education’s 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

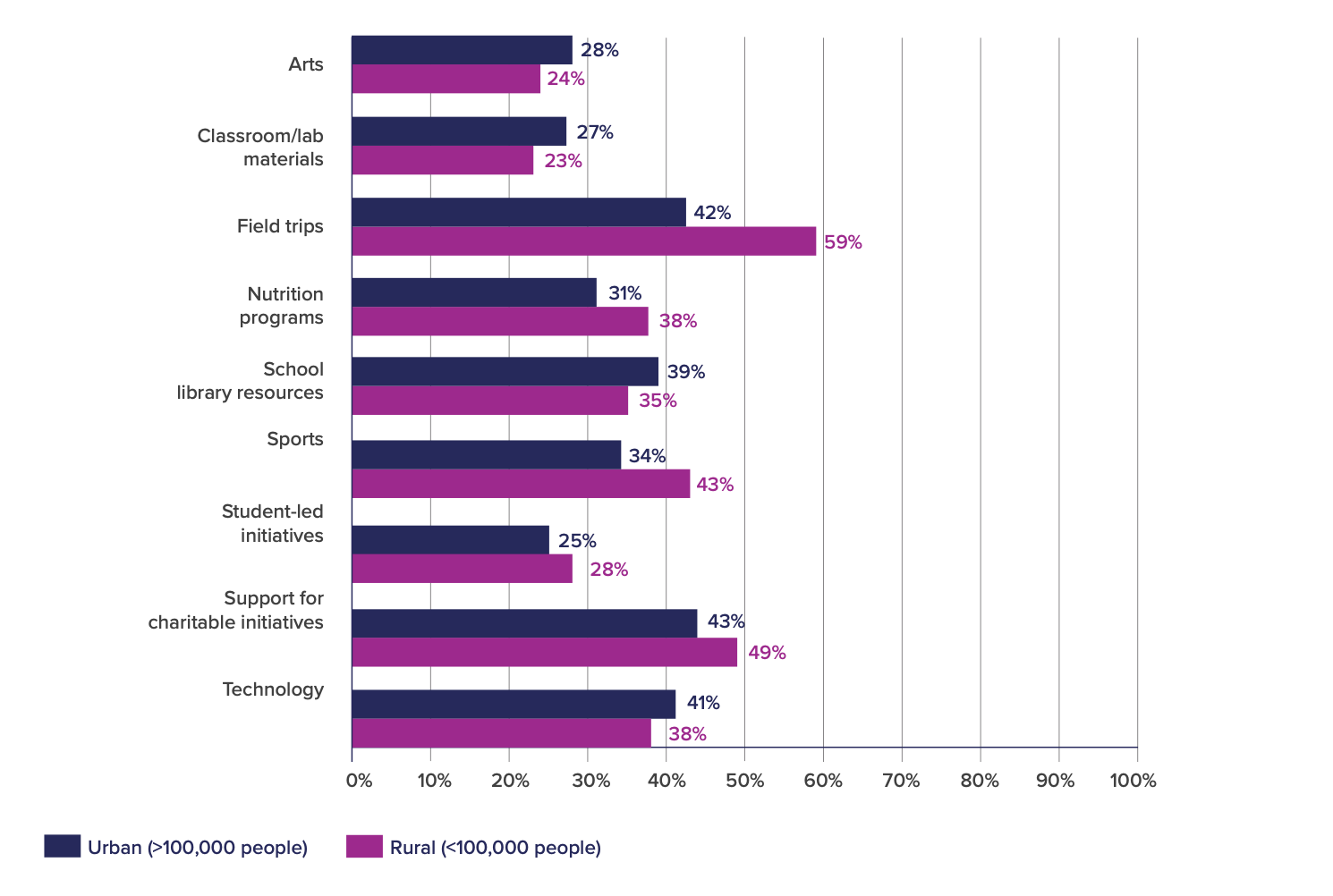

Differences were also found between how schools in urban areas use fundraising money compared to schools in rural areas. Rural schools were more likely to report fundraising for field trips, sports, and nutrition programs. Numerous principals attributed this finding to the associated costs of being in remote areas where more travel is necessary to access activities such as participating in sports competitions, visiting exhibits, and seeing performances.

“Our geographical area is very rural, and many families cannot afford to travel and experience sports and arts venues, etc., so we do our best to provide activities free of charge, as well as offer food and clothing for our families in need.”

Elementary school principal, Northern Ontario

Differences in fundraising initiatives in urban vs rural schools

Figure 7: What Ontario schools fundraise for, by population size

Source: People for Education’s 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

“Many more families are experiencing financial hardship. It is becoming more and more difficult to fundraise. Costs for co-curricular activities have skyrocketed, but the per pupil allocation from the board/ministry has not changed to reflect inflation. We are doing more with less money.”

Secondary school principal, Central Ontario

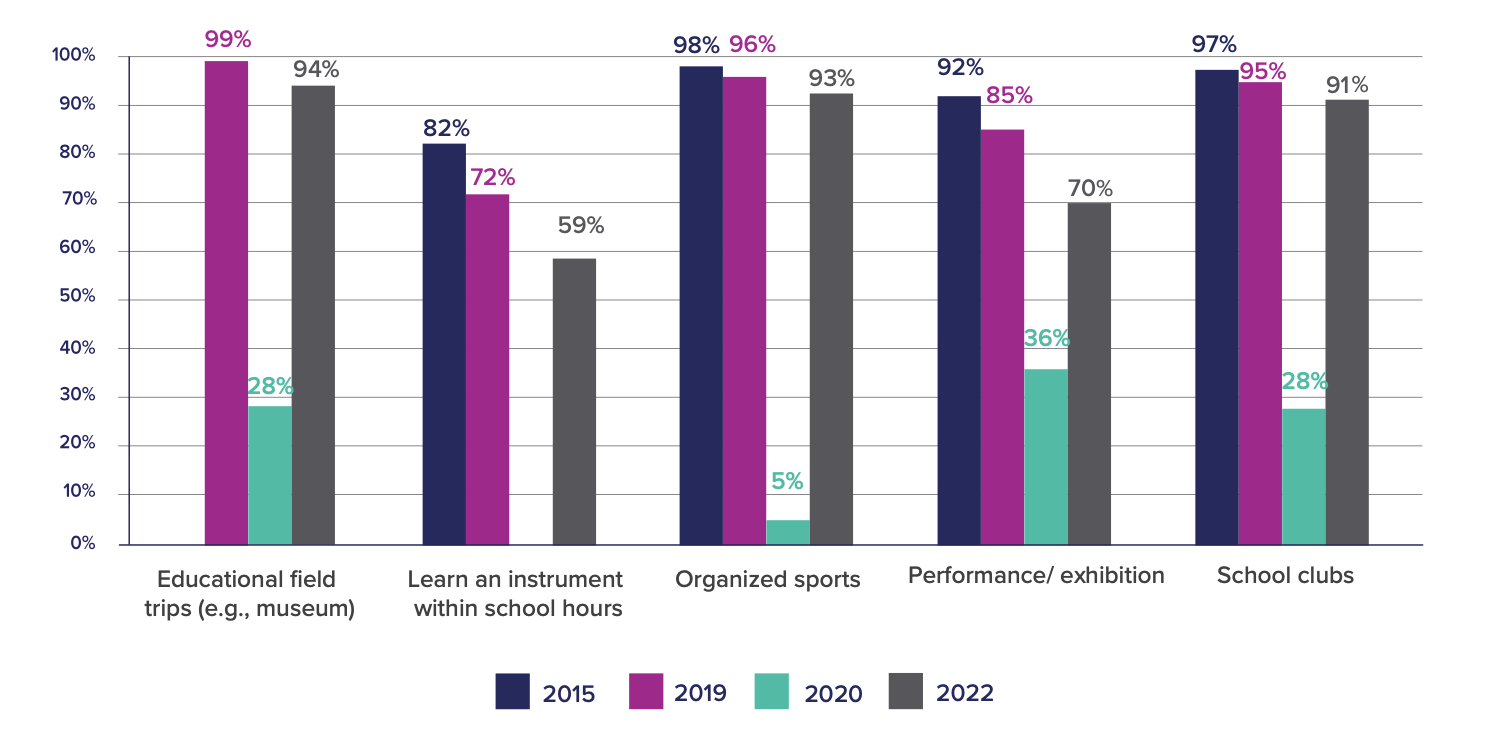

In 2021, during the height of the pandemic, People for Education reported on the huge decrease in extracurricular and school activities offered in Ontario elementary and secondary schools.4 Two years later, findings from the 2022-23 school year showed significant recovery as students returned to in-person learning, but not without challenges for the school staff.

“It is very difficult to run clubs and other extracurricular activities. Staff are overloaded and burnt out. They do not have the drive to run extra clubs.”

Elementary school principal, Eastern Ontario

Proportion of Ontario elementary and secondary schools offering extracurricular and activities, pre- and post-pandemic

Figure 8: Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario offering extracurricular and school activities, 2015- 16, 2019-20, 2020, 2022-23

Source: People for Education’s 2015-16, 2019-20, fall 2020, and 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

Principals said that they noticed an increased student interest in participating in extracurricular clubs and school activities during the 2022-2023 school year after many of the opportunities were paused during the pandemic. However, for many schools, transitioning back to offering a full range of these opportunities for students has been a challenge because it is adding pressure on an already overworked school staff.

Organizing school activities and extracurriculars is voluntary for teachers and staff, and principals said that they noticed fewer staff had the time and energy to dedicate to the activities, in part because of ongoing staff shortages and increased student needs in the classroom.

“Teachers are having difficulty meeting the socio-emotional needs of students and are exhausted; therefore, they are not volunteering for as many things outside of their classroom programs. ”

Elementary school principal, Greater Toronto Area

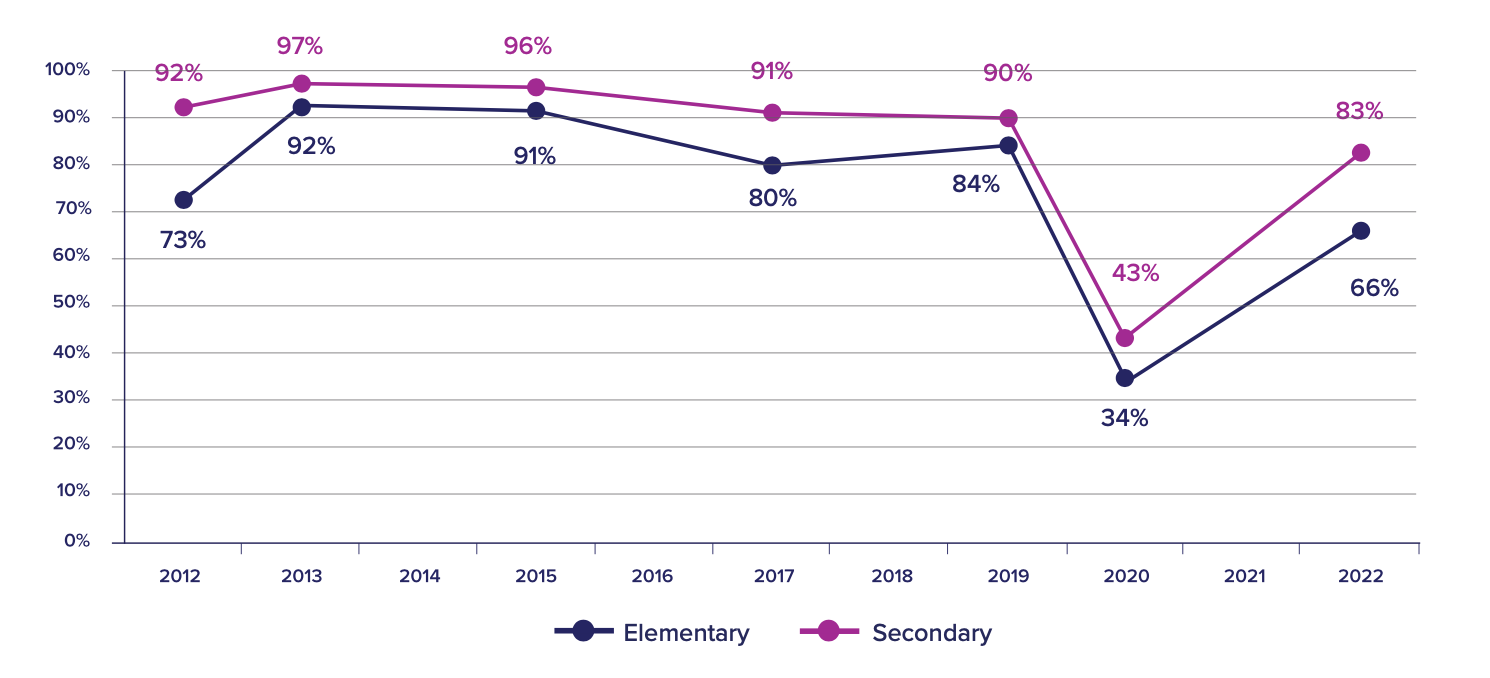

Arts-based opportunities, which were greatly reduced during the pandemic, have also shown recovery in the 2022-23 school year but to a lesser extent than other opportunities, like sports, clubs, and field trips.

In 2019-20, 84% of elementary schools reported offering opportunities for students to participate in a performance/exhibition compared to 34% in fall 2020 and 66% in 2022-23. For secondary schools, 90% of schools reported offering opportunities to participate in a performance/exhibition in 2019-20 compared to 43% in fall 2020 and 83% in 2022-23. The proportion of schools reporting that their students had the opportunity to learn an instrument within school hours fell from 68% in 2019-20 to 55% in 2022-23 for elementary schools and from 87% in 2019-20 to 74% in 2022-23 for secondary schools.

Proportion of Ontario schools offering opportunities to participate in a performance or exhibition, change over time

Figure 9: Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario facilitating opportunities to participate in a performance/exhibition (e.g., play, dance, art exhibition), 2012-2022

Source: People for Education’s 2012-13, 2013-14, 2015-16, 2017-18, 2019-20, fall 2020, and 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey

Student participation in all clubs and sports is high this year as it has been missing for the last two years. It has increased confidence in many students.

Elementary school principal, Central Ontario

Participation in school activities and extracurriculars benefits students in several ways, across various stages of education and life. A breadth of research indicates that extracurricular activities such as sports, arts, clubs, and community programs can positively affect students’ mental and emotional well-being, including decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression, improved self- concept and confidence, stronger feelings of connectedness and belonging, and higher levels of life satisfaction.5 A study of 28,000 middle school students in British Columbia also found that students who engaged in extracurricular activities were significantly less likely to engage in the excessive use of screen-based activities, a factor associated with poor mental and physical health.6

Students who participate in extracurricular activities also gain skills and competencies beyond the basics such as thinking creatively and critically, collaborating, communicating effectively, and developing a sense of self and society – which are essential to navigating the rapidly changing world we live in.7 There is also evidence to indicate that students’ participation in extracurricular activities is associated with greater educational engagement, higher rates of high school completion, increased academic success, and employability.8

Schools are so much more than a place where students are taught to meet curriculum expectations. Extracurricular and school activities provide students with the chance to develop soft skills such as teamwork and leadership, as well as explore interests outside of their course subjects. While many of these activities are returning to pre-pandemic levels, it is important to consider what resources are necessary to sustain them (e.g., education staff, budget, etc.) as well as to ensure that students’ access is not dictated by whether they live in an urban, rural, high-, or low-income area. The role of government is critical to the development of policies and initiatives that support all aspects of a quality education.

Source: People for Education 2019

The latest Ontario provincial budget was announced in March 2023 and the Better Schools and Student Outcomes Act was released in April 2023, but neither includes a plan for addressing equity overall, or accessibility to extracurricular activities and other broader learning opportunities.9 While these are opportunities that should be accessible to all students, the findings from our annual survey illustrate inequities depending on whether students live in a rural or urban region, or their school is in a high- or low-income neighbourhood. There is evidence to suggest that when governments mandate supports and opportunities that are beneficial to students, it leads to more equitable access to those opportunities across schools.10

- People for Education recommends that the province develop policy and funding that recognizes the far-reaching benefits that extracurricular and school activities provide for students and ensures that all students have equitable access to these vital components of a quality education.

- People for Education continues to recommend that the province convene a Health and Education Task Force including experts, practitioners, and students to provide input on government policy before it is implemented, and to help design new policy and funding models to support things like extracurricular activities, arts and sports, and clubs.

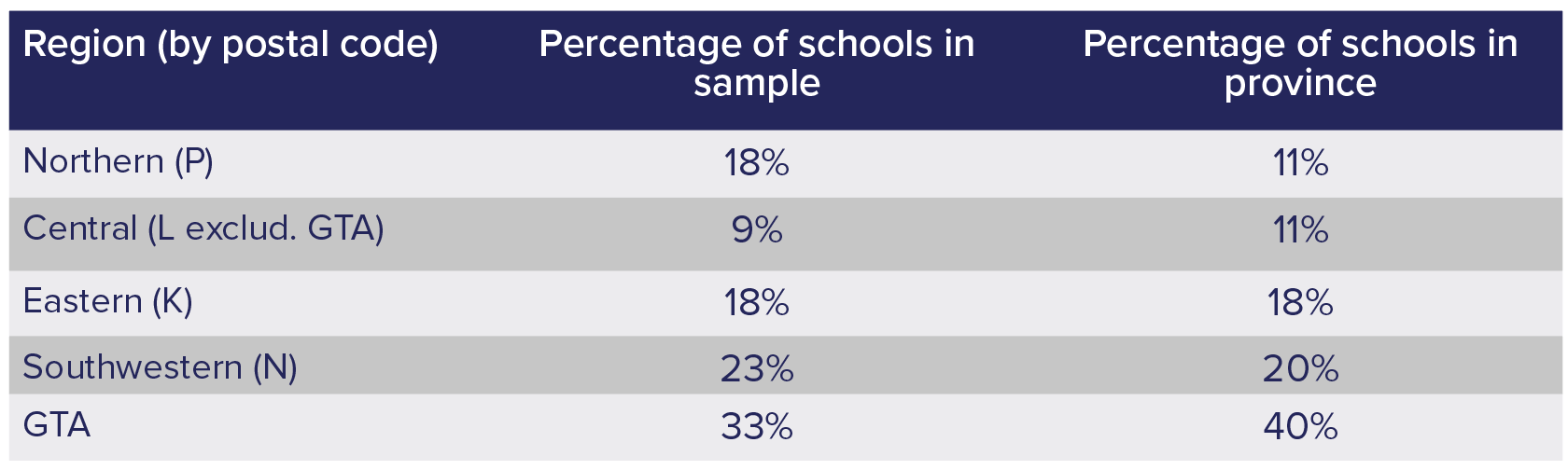

This report is based on data from the 1,044 schools from all 72 publicly funded Ontario school boards that participated in the 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS). Longitudinal data comparisons are based on the data collected from the elementary and secondary schools that participated in People for Education’s 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15, 2015-16, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018-19, 2019-20, and fall 2020 AOSS. Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and quoted material in this report originate from People for Education’s 2022-23 AOSS, the 26th annual survey of elementary schools, and the 23rd annual survey of secondary schools in Ontario. Surveys from the 2022-23 AOSS were completed online via SurveyMonkey in both English and French in the fall of 2022. Survey responses were disaggregated to examine survey representation across provincial regions (see table below). Schools were sorted into geographical regions based on the first letter of their postal code. The GTA region includes schools with M postal codes as well as those with L postal codes located in GTA municipalities.11

In order to analyze a school’s geographical circumstances, each school’s postal code was used to identify the population of the town or city in which the school is located, based on 2021 Census data. Statistics Canada uses population size to classify a population centre as small, medium, or large urban. The population breakdown is as follows: small population centres have a population between 1,000 and 29,999, medium population centres have a population between 30,000 and 99,999, and large urban population centres have a population of 100,000 or more.12 While Statistics Canada has various definitions of a rural area, for the purposes of this analysis, a rural area has a population under 1,000. In order to conduct data analysis with an adequate sample size, schools in rural, small, and medium areas (n = 496) were compared against schools in large urban areas (n = 548), unless otherwise specified. Therefore, in this report, “rural” refers to schools that are located in population centres of fewer than 100,000 people, whereas “urban” refers to schools located in population centres of 100,000 people or more.

During analysis, data collected from the survey were matched with the Median Census Family Income of Schools based on School Enrolment by Student Residential Postal Code, Preliminary 2021-2022, which was provided to PFE through a Request for Information from the Ontario Ministry of Education’s Education Statistics and Analysis Branch. The Median Census Family Income information was derived from the 2021 Census for all the dissemination areas associated to a school based on the weighted enrolment by residential postal code of its students. Schools were then sorted from highest to lowest income based on this measure. In this report, the top 25% of schools based on Weighted Census Family Income are considered “high-income” (n = 257, average income = $130,035) and the bottom 25% are considered “low-income” (n = 257, average income = $71,074), unless otherwise specified.

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using inductive analysis. Researchers read responses and coded emergent themes in each set of data (i.e., the responses to each of the survey’s open-ended questions). The quantitative analyses in this report are based on descriptive statistics. The primary objective of the descriptive analyses is to present numerical information in a format that is accessible to a broad public readership. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. All calculations have been rounded to the nearest whole number and may not total 100% in displays of disaggregated categories. All survey responses and data are kept confidential and stored in conjunction with TriCouncil recommendations for the safeguarding of data.

For questions about the methodology used in this report, please contact the research team at People for Education: [email protected].

1 Christison, Claudette. 2013. “The Benefits of Participating in Extracurricular Activities.” BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education 5 (2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1230758.pdf. 2 Kalubi, Jodi, Teodora Riglea, Robert J. Wellman, Jennifer O’Loughlin, Katerina Maximova. 2023. “Availability of health-promoting interventions in high schools in Quebec, Canada, by school deprivation level.” Health Promotion Chronic Disease Prevention Canada 43(7):321-9. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.7.02.

3 Butler, Colin. “The easiest way to solve the school bus driver shortage? ‘Pay them more,’ says region’s bus boss.” CBC News. January 12, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/london-ontario-school-bus-1.6710642.

4 People for Education. 2021. “The Far-Reaching Costs of Losing Extracurricular Activities During COVID-19.” https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/People-for-Education-The-Cost-of-Losing-Extra-Curricular- Activities-April-2021.pdf.

5 LaForge-MacKenzie, Kaitlyn, Katherine Tombeau Cost, Kimberley C. Tsujimoto, Jennifer Crosbie, Alice Charach, Evdokia Anagnostou, Catherine S. Birken, et al. 2022. “Participating in Extracurricular Activities and School Sports during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations with Child and Youth Mental Health.” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 4 (August): 936041. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.936041; Oberle, Eva, Xuejun R. Ji, Carly Magee, Martin Guhn, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2019. “Extracurricular Activity Profiles and Wellbeing in Middle Childhood: A Population-Level Study.” Edited by Juan Carlos Perez Gonzalez. PLOS ONE 14 (7): e0218488. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218488; Zarobe L, Bungay H. 2017. The role of arts activities in developing resilience and mental wellbeing in children and young people a rapid review of the literature. Perspectives in Public Health. 2017;137(6):337-347; Oberle, Eva, Xuejun Ryan Ji, Martin Guhn, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2019. “Benefits of Extracurricular Participation in Early Adolescence: Associations with Peer Belonging and Mental Health.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48 (11). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01110-2.

6 Oberle, Eva, Xuejun Ryan Ji, Salima Kerai, Martin Guhn, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2020. “Screen Time and Extracurricular Activities as Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Health in Adolescence: A Population-Level Study.” Preventive Medicine 141 (December): 106291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106291; Twenge, Jean M., and W. Keith Campbell. 2018. “Associations between Screen Time and Lower Psychological Well-Being among Children and Adolescents: Evidence from a Population-Based Study.” Preventive Medicine Reports 12 (12): 271–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003; Stiglic, Neza, and Russell M Viner. 2019. “Effects of Screentime on the Health and Well-Being of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Reviews.” BMJ Open 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191.

7 People for Education. 2019. “The New Basics”. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/PFE-The_New_Basics-combined.pdf; Olibie, Eyiuche Ifeoma, and Madumere Ifeoma. “Curriculum enrichment for 21st century skills: A case for arts based extracurricular activities for students.” International Journal of Recent Scientific Research 6, no. 1 (2015): 4850-4856.; Christison, Claudette. 2013. “The Benefits of Participating in Extracurricular Activities.” BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education 5 (2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1230758.pdf.

8 O’Donnell, Chloé, Rachel Sandford, and Andrew Parker. 2019. “Physical Education, School Sport and Looked-After-Children: Health, Wellbeing and Educational Engagement.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (6): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1628731; Arriagada, Paula. 2015. “Insights on Canadian Society Participation in Extracurricular Activities and High School Completion among Off-Reserve First Nations People.” Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2015001/article/14175-eng.pdf; Wretman, Christopher J. 2017. “School Sports Participation and Academic Achievement in Middle and High School.” Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 8 (3): 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1086/693117; Aliu, John, and Clinton Aigbavboa. 2021. “Reviewing the Roles of Extracurricular Activities in Developing Employability Skills: A Bibliometric Review.” International Journal of Construction Management, November, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2021.1995807; Ribeiro, Norberto, Carla Malafaia, Tiago Neves, and Isabel Menezes. 2023. “The Impact of Extracurricular Activities on University Students’ Academic Success and Employability,” 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2023.2202874.

9 Government of Ontario. 2023. “2023 Ontario Budget | Building a Strong Ontario.” Accessed July 14, 2023. https://budget.ontario.ca/2023/index.html; Government of Ontario. 2023. “Better Schools and Student Outcomes Act, 2023, S.O. 2023, c. 11 – Bill 98”. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/s23011.

10 Kalubi, Jodi, Teodora Riglea, Robert J. Wellman, Jennifer O’Loughlin, Katerina Maximova. 2023. “Availability of health- promoting interventions in high schools in Quebec, Canada, by school deprivation level.” Health Promotion Chronic Disease Prevention Canada 43(7):321-9. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.7.02.

11 City of Toronto. n.d. “City Halls – GTA Municipalities and Municipalities Outside of the GTA.” Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www.toronto.ca/home/311-toronto-at-your-service/find-service-information/article/?kb=kA06g000001cvbdCAA.

12 Statistics Canada. 2022. “Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021 – Population centre (POPCTR).” Updated on February 9, 2022. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/dict/az/Definition-eng.cfm?ID=geo049a.

Aliu, John, and Clinton Aigbavboa. 2021. “Reviewing the Roles of Extracurricular Activities in Developing Employability Skills: A Bibliometric Review.” International Journal of Construction Management, November, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2021.1995807.

Arriagada, Paula. 2015. “Insights on Canadian Society Participation in Extracurricular Activities and High School Completion among Off-Reserve First Nations People.” Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2015001/article/14175-eng.pdf.

Butler, Colin. “The easiest way to solve the school bus driver shortage? ‘Pay them more,’ says region’s bus boss.” CBC News. January 12, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/london-ontario-school-bus-1.6710642.

Christison, Claudette. 2013. “The Benefits of Participating in Extracurricular Activities.” BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education 5 (2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1230758.pdf.

City of Toronto. n.d. “City Halls – GTA Municipalities and Municipalities Outside of the GTA.” Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www.toronto.ca/home/311-toronto-at-your-service/find-service-information/article/?kb=kA06g000001cvbdCAA.

Government of Ontario. 2023. “2023 Ontario Budget | Building a Strong Ontario.” Accessed July 14, 2023. https://budget.ontario.ca/2023/index.html.

Government of Ontario. 2023. “Better Schools and Student Outcomes Act, 2023, S.O. 2023, c. 11 – Bill 98”. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/s23011.

Kalubi, Jodi, Teodora Riglea, Robert J. Wellman, Jennifer O’Loughlin, Katerina Maximova. 2023. “Availability of health-promoting interventions in high schools in Quebec, Canada, by school deprivation level.” Health Promotion Chronic Disease Prevention Canada 43(7):321-9. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.7.02.

LaForge-MacKenzie, Kaitlyn, Katherine Tombeau Cost, Kimberley C. Tsujimoto, Jennifer Crosbie, Alice Charach, Evdokia Anagnostou, Catherine S. Birken, et al. 2022. “Participating in Extracurricular Activities and School Sports during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations with Child and Youth Mental Health.” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 4 (August): 936041. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.936041.

Oberle, Eva, Xuejun R. Ji, Carly Magee, Martin Guhn, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2019. “Extracurricular Activity Profiles and Wellbeing in Middle Childhood: A Population-Level Study.” Edited by Juan Carlos Perez Gonzalez. PLOS ONE 14 (7): e0218488. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218488.

Oberle, Eva, Xuejun Ryan Ji, Martin Guhn, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2019. “Benefits of Extracurricular Participation in Early Adolescence: Associations with Peer Belonging and Mental Health.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48 (11). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01110-2.

Oberle, Eva, Xuejun Ryan Ji, Salima Kerai, Martin Guhn, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2020. “Screen Time and Extracurricular Activities as Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Health in Adolescence: A Population-Level Study.” Preventive Medicine 141 (December): 106291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106291.

O’Donnell, Chloé, Rachel Sandford, and Andrew Parker. 2019. “Physical Education, School Sport and Looked-After-Children: Health, Wellbeing and Educational Engagement.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (6): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1628731.

Olibie, Eyiuche Ifeoma, and Madumere Ifeoma. 2015. “Curriculum enrichment for 21st century skills: A case for arts based extracurricular activities for students.” International Journal of Recent Scientific Research 6, no. 1 (2015): 4850-4856.

People for Education. 2019. “The New Basics”. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/PFE-The_New_Basics-combined.pdf.

People for Education. 2021. “The Far-Reaching Costs of Losing Extracurricular Activities During COVID-19.” Accessed April 26, 2023. https://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/People-for-Education-The-Cost-of-Losing-Extra-Curricular-Activities-April-2021.pdf.

Ribeiro, Norberto, Carla Malafaia, Tiago Neves, and Isabel Menezes. 2023. “The Impact of Extracurricular Activities on University Students’ Academic Success and Employability,” 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2023.2202874.

Statistics Canada. 2022 “Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021 – Population centre (POPCTR).” Updated on February 9, 2022. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/dict/az/Definition-eng.cfm?ID=geo049a.

Stiglic, Neza, and Russell M Viner. 2019. “Effects of Screentime on the Health and Well-Being of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Reviews.” BMJ Open 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191.

Twenge, Jean M., and W. Keith Campbell. 2018. “Associations between Screen Time and Lower Psychological Well-Being among Children and Adolescents: Evidence from a Population-Based Study.” Preventive Medicine Reports 12 (12): 271–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003.

Wretman, Christopher J. 2017. “School Sports Participation and Academic Achievement in Middle and High School.” Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 8 (3): 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1086/693117.

Zarobe L, Bungay H. 2017. The role of arts activities in developing resilience and mental wellbeing in children and young people a rapid review of the literature. Perspectives in Public Health. 2017;137(6):337-347. doi: 10.1177/1757913917712283.