This report, based on the results from our Annual Ontario School Survey, looks at the policies, programs, and resources available to support students’ career and life planning. It finds that Ontario may be falling behind at a time when there is growing pressure to prepare students for a rapidly changing, increasingly complex future.

Roadmaps and roadblocks: Career and life planning, guidance, and streaming in Ontario’s schools

The reality is that the challenges and opportunities faced by students in this century are unlike those of any previous generation, and that all students today require specific knowledge and skills in education and career/life planning to support them

in making sound choices throughout their lives.– Creating Pathways to Success: An Education and Career/Life Planning Program for Ontario Schools (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013)

One of the main purposes of schooling is to prepare students for a rapidly changing future. In today’s world, hyper-charged technological and social change – from automation and artificial intelligence to climate change and increasing inequality – has increased the pressure on schools, students, and their families.

Challenges of this scope affect everything students should learn –

from literacy and STEM, to citizenship, social-emotional learning, problem-solving, and creativity. There are multiple reports attempting to articulate what today’s graduates will need, including new “clusters” of skills such as citizenship, healthy living, creativity, and collaboration, as well as attributes such as adaptability and an orientation to lifelong learning, so that they can move between jobs (e.g. Grant, 2016; OECD, 2018; RBC, 2018).

As students develop – academically and personally – the school system itself provides support and navigational aids. More than that, it helps shape opportunities for the future. And sometimes, it creates barriers.

In Ontario, one area of the academic program focuses specifically on preparing students for the unknown: career and life planning. Ontario’s Creating Pathways to Success policy includes guidelines for the use of portfolios, school-based career and life planning committees, and professional development for teachers, to help students navigate their future.

Ontario has the policy, but there are a number of challenges in ensuring that all students can successfully navigate their way through school to the future they choose.

This report is based on data from the 1254 schools that participated in People for Education’s Annual Ontario School Survey. Among the findings:

- Only 23% of elementary schools have guidance counsellors. While this is a sizeable increase over last year, these supports are mostly unavailable for students making the transition to high school.

- In secondary schools, guidance counsellors are, on average, responsible for 375 students each.

- It is mandatory for every student in secondary school to have an Individual Pathways Plan (IPP), but only 57% of high schools report that all students have IPPs.

- Only 23% of secondary schools that require transfer courses for students who want to transfer from applied to academic courses, offer those courses.

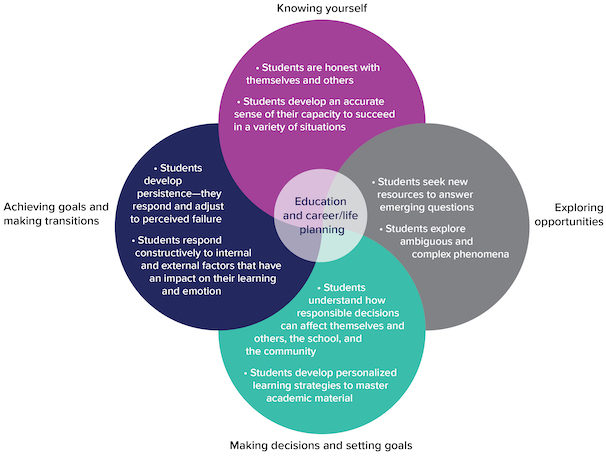

The Creating Pathways to Success policy is framed around a four-step inquiry process for all students, from kindergarten through to graduation:

- Knowing yourself: Who am I?

- Exploring opportunities: What are my opportunities?

- Making decisions and setting goals: Who do I want to become?

- Achieving goals and making transitions: What is my plan for achieving my goals?

Working through these questions aims to help students plan, and also supports them in developing competencies and skills in areas such as social-emotional development, resiliency, and problem solving. The Creating Pathways policy states that this four-step inquiry process is to be embedded “across all subjects, courses, and daily learning activities” for all schools (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013, p. 10).

People for Education – working with experts from across Canada and internationally – has defined a set of competencies that students need to go on to lead happy, healthy, economically secure, civically engaged lives. (People for Education, 2016) Figure 1 maps some of those competencies across the four-step Creating Pathways framework.

Provinces such as Alberta, British Columbia, and Québec have embedded these core competencies throughout their curricula (Alberta Ministry of Education, 2016; British Columbia Ministry of Education, n.d.; Québec Ministry of Education, n.d.), but Ontario has not.

Figure 1

Competencies for career and life planning

These are some examples of core competencies from People for Education’s Measuring What Matters initiative (People for Education, 2016), overlaid onto the four-step inquiry process from Ontario’s career and life planning policy (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013).

Supporting self-knowledge and exploration

This is just one more thing

for teachers to manage when they are already overwhelmed with covering curriculum and managing behaviour, anxiety, learning needs, parents, etc.

Elementary principal, York Region DSB

Under the original Creating Pathways policy, every student in elementary school up to grade 6 was required to develop All About Me port- folios, and use them to record their growing sense of themselves and the opportunities available to them. It was also mandatory that every school have a Career/Life Planning Program Advisory Committee. These committees are supposed to include school administration, guidance counsellors, teachers, parents, community members, and students. Their purpose is to ensure that the school’s career and life planning program is comprehensive – embedded and supported across the curriculum and across the school community.

As the All About Me portfolios are not mandatory, and they are work intensive, teachers do not choose to use them.

Elementary principal, Kawartha Pine Ridge DSB

In 2017, People for Education reported that All About Me portfolios were used by all K-6 students in only 32% of elementary schools, and only 15% of elementary schools had Career/Life Planning Advisory Committees. Shortly afterward, the provincial government changed the requirements, and made the All About Me portfolio and the advisory committees an “optional strategy” (Rodrigues, 2017). Since that time, the percentage of schools reporting all students have All About Me portfolios has declined to 19%, and only 14% have Career/Life Planning Advisory Committees.

In the 14% of elementary schools that have Career/Life Planning Advisory Committees, membership is mostly staff. Very few schools report involvement of parents (12%), community members (7%), or students (14%). However, having a committee appears to have an impact on professional development for teachers around career and life planning: 49% of elementary schools with advisory committees offer professional development for teachers, compared to 17% of schools without committees.

It is difficult to fit everything into the instructional program, as we have a strong focus on literacy and numeracy at our school.

Elementary principal, Keewatin-Patricia DSB

One of the reasons for the lack of participation in the initiative may be that elementary schools have limited resources beyond the classroom teacher to support students’ career and life planning.

When we first started asking about implementing the Creating Pathways policy, principals reported a number of challenges, including a lack of professional development, limited time in the school day, and a lack of technical support for the online components of the policy (People for Education, 2017).

The K to grade 6 teachers need assistance from the Guidance Teacher for the All About Me portfolio. The Guidance Teacher only visits our school for one half day twice a month, so the focus is mostly on grades 7 & 8 and dealing with students who have behaviour issues.

Elementary principal, Toronto Catholic DSB

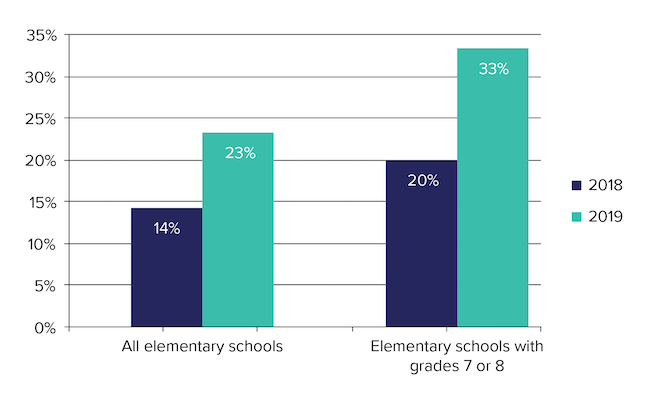

A lack of guidance support is also among the challenges principals report in implementing Creating Pathways. This year, only 23% of all elementary schools have a guidance counsellor, and the vast majority are part-time (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Guidance counsellors in elementary schools, full- or part-time

The middle years – making the transition to secondary school

Elementary guidance counsellors are new position this year – this has been great for getting the IPPs started.

Elementary school,

Simcoe Muskoka Catholic DSB

While grades 7 and 8 are still considered elementary school, they are key years in defining students’ future opportunities. Among many other tasks, guidance counsellors support students in choosing courses for high school, as well as their ongoing inquiry process within the Creating Pathways framework.

First year with increased guidance support from 0.1 to 0.5 FTE and that is making a big difference in terms of the support/planning we are able to provide.

Elementary principal, Peel DSB

In 2017/18, the Ministry of Education provided an additional $46 million to fund guidance counsellors for grades 7 and 8 at a ratio of 385 students to one guidance counsellor – an improvement from the previous funding, which was provided at a ratio of 1000 students for each guidance counsellor (Davis, 2018).

This year, 33% of elementary schools with grades 7 and 8 have a guidance counsellor, up from 20% last year. However, in August of 2018, the funding policy changed, so that school boards can spend what had been targeted guidance funding for elementary schools on any strategy relating to careers or mental health, in either elementary or secondary schools (Rodrigues, 2018).

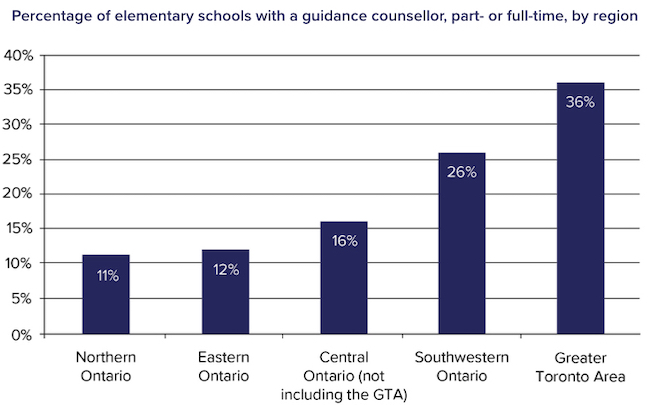

Despite the funding increases, guidance counsellors continue to be unevenly distributed across the province. Elementary schools in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) are over three times more likely to have a guidance counsellor – either part- or full-time – than elementary schools in the North (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Percentage of elementary schools with a guidance counsellor, part- or full-time, by region

Plans and choices in grades 7 and 8

While the province made All About Me portfolios optional for kindergarten to grade 6, the Creating Pathways policy still mandates that all students in grades 7 to 12 have an Individual Pathways Plan (IPP) – which is a continuation of the All About Me portfolio. Students from grades 7

to 12 (and their teachers) are expected to use the IPP as the “primary planning tool for students as they move through the grades towards their initial post-secondary destination” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013, p. 18).

This year’s data show that while the mandatory policy is there on paper, the reality in schools is different. Only 74% of elementary schools

with grades 7 and 8 report that all students have an IPP, and in 15% of schools, no students have IPPs.

The high school principal and guidance counsellor visit. And we have two open houses (one for our 8th graders as well as one for our parents).1

Elementary principal, Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir

1:Translated from French. Original comment: “Visite de la direction et l’orienteur de notre école secondaire. Invitation à deux portes ouvertes (une pour nos élèves de la 8e ainsi qu’une pour nos parents).”

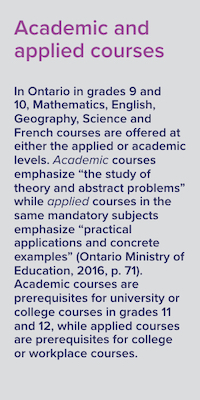

Choosing courses – choices now may limit choices later

Until the end of grade 8, all students study the same curriculum. However, before they move on to grade 9, students must choose between applied and academic courses for their grade 9 year – decisions that may have long-lasting consequences.

Students and their parents may not be getting sufficient information to make informed choices. When asked about the main source of information regarding course selection for students in grade 8 and their parents:

- 55% of schools report that their main source is information nights • 14% report it is one-on-one counselling

- 10% mainly use handouts

- 5% report primarily using email

A number of schools reported innovative new programs, where staff from both grade 8 and high schools worked together to help answer questions.

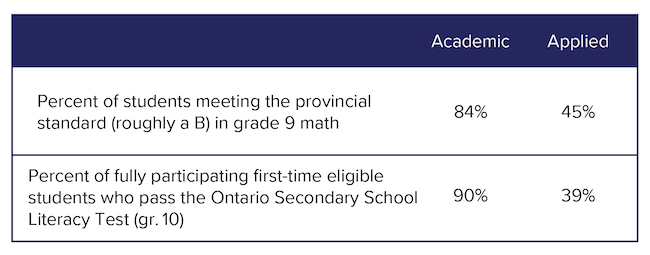

Significant differences in outcomes

According to data from the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO), there are more than 33,000 students in grade 9 applied courses in Ontario. Research has shown that these students are more likely to come from lower income families, and are much less likely to graduate from high school (Brown & Tam, 2017a; People for Education, 2015).

Information about the outcomes of applied vs. academic courses is not usually part of the information sessions or handouts for students and parents. While many educators continue to recommend applied courses because they believe struggling students have a better chance of success there, there are significant differences in outcomes facing students enrolled in applied courses.

Information about the outcomes of applied vs. academic courses is not usually part of the information sessions or handouts for students and parents. While many educators continue to recommend applied courses because they believe struggling students have a better chance of success there, there are significant differences in outcomes facing students enrolled in applied courses.

Students in applied courses are much less likely to graduate from high school, and less than half of them go on to college. Recent research from the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) showed that 88% of students in academic programs of study2 graduated, as opposed to 59% of students in applied courses (Brown & Tam, 2017a). Other TDSB research showed that students in academic courses are much more likely to be accepted into post-secondary education than those in applied (82% vs. 48%). And even though applied courses are intended to lead to college, workplace, and apprenticeships, only 37% of those in an applied program of study are accepted into college (Brown & Tam, 2017b).

2: An applied program of study means that students take a majority of their courses at the applied level; an academic program of study means that students take a majority of their courses at the academic level.

Do applied courses depress achievement?

We have phased out grade nine applied French and grade nine applied Geography. All grade nine students take French and Geography at the academic course type. Based on the belief that all students can learn, progress, and achieve with time, support, and caring teacher, a culture of high expectations allows engaged students who attend regularly to have a better academic foundation to be successful at the subsequent grade level.

Secondary principal, Lambton Kent DSB

Research by EQAO that follows students over time shows that students with comparable academic background (i.e. similar scores, even poor scores, on grade 6 tests) are far more likely to do better in academic than applied courses (EQAO, 2018).

The results over the past decade consistently show that students in applied courses are much less likely to meet the provincial standard in math or literacy (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Outcomes in EQAO secondary school assessments, 2017-18

These results are consistent with long-standing international research that suggests grouping students by perceived ability or academic destination actually depresses student achievement (Brooks, 1985; Curtis, Livingstone, & Smaller, 1992; Hanushek & Woessmann, 2006; Hattie, 2009; Krahn & Taylor, 2007). Based on this literature and international test results, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) recommends that schools defer streaming students into later secondary school (2013).

Applied courses may depress achievement in another way. A recent analysis by the TDSB suggests that achievement in applied courses does not “count” in the way that achievement in academic courses does. For example, students with an A-range mark in applied math have the same likelihood of going on to post-secondary (college or university) as students with a D-range grade in academic math (Brown, 2018).

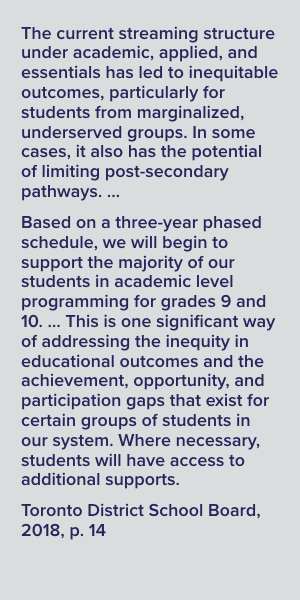

Who is streamed into applied courses and why is it a problem?

A number of factors affect which students take applied courses in grade 9.

Students’ Individual Pathway Plans (IPPs) in grade 8 can have an impact on their trajectory into high school – 84% of elementary schools report that students’ IPPs are used to inform course recommendations (i.e. applied/academic) for students going into secondary school. Aspects of the IPP that may be used include things like students’ self-selected career destinations and their past academic achievement. There has also been extensive research showing that racialized students and students from lower income families are more likely to go into applied courses in high school (James & Turner, 2017; Robson Anisef, Brown, & Parekh, 2018).

Over the past five years, there has been more and more information available about problems with streaming students into different course types. Some schools and school boards are going further to actively steer students towards the pathway associated with better outcomes.

Over the past five years, there has been more and more information available about problems with streaming students into different course types. Some schools and school boards are going further to actively steer students towards the pathway associated with better outcomes.

Last year, based on years of its own data and international research, the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) adopted a three-year plan to move most students into academic programming in grade 9, with a strong emphasis on planning that starts as early as grade 7.

The ultimate purpose of the TDSB initiative – which follows successful pilot projects in a number of schools – is to boost achievement and ensure “improved post-secondary choice at the work, college, apprenticeship, and university levels for all students” (TDSB, 2018, p. 15).

Transferring across streams – how much flexibility is there?

We have gap-closing classes in grade 9 to attempt to move grade 8 kids to the academic stream and we have also provided summer classes prior to grade 9 for our feeder students. It has been very successful.

Secondary principal, Hamilton Wentworth Catholic DSB

Adolescence is a time of significant change. As students develop and explore alternatives, schools sometimes lack flexibility to support them when they change direction or realize that their new plans require them to take courses with prerequisites that didn’t seem important in grade 8 or 9.

Students who want to transfer from applied to academic courses in grades 9 and 10 continue to face significant barriers. In 47% of high schools, principals report that students transfer from applied to academic courses “never” or “not very often.” There has been little change in this statistic over the past five years. Just over a quarter (27%) of schools require students to take a transfer course before they change from applied to academic, and most of those (77%) do not offer the transfer course during school hours.

We offer students the opportunity to achieve an applied credit rather than an academic if they are misplaced. We have also de-streamed our grade 9 Science and Geography in order to help students and parents understand the best level for the student to work at moving forward.

Secondary principal, Ottawa-Carleton DSB

We have meetings with students, teachers, and parents when they are in grade 8….Also, we timetable applied/college and academic/university courses during the same time so that transferring from one to the other can be possible.

Secondary principal, York Region DSB

Career and life planning and guidance support

As students progress through secondary school, they face many choices, and need to take active steps to prepare themselves for life after high school.

The Creating Pathways policy, with its four-step inquiry process, is intended to provide students with greater capacity to make those choices.

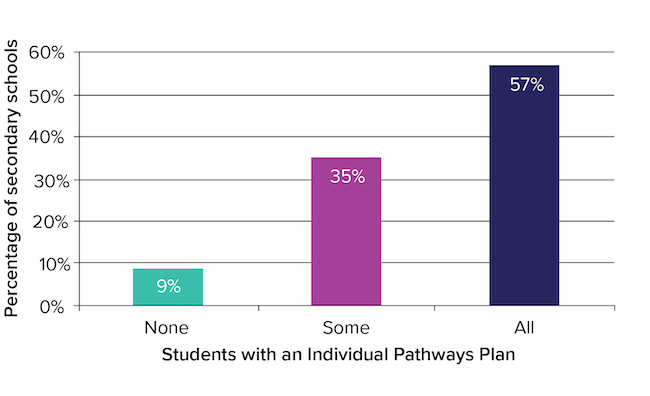

Under the policy, it remains mandatory for all students in secondary school to have an Individual Pathways Plan (IPP). However, in 2019, only 57% of secondary schools report that all of their students have an IPP, and in 9% of schools, no students have IPPs (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Portfolio use in secondary schools

Guidance counsellors have many roles in Ontario high schools, including supporting students who are struggling with their mental health, making course choices, or navigating special education. But they play a particularly vital role in career and life planning.

Nearly every high school in the province (98%) has at least a part-time guidance counsellor. However, the average ratio per school of students to guidance counsellors is 375 to one, and in 10% of secondary schools the ratio is as high as 687 to one.

In most secondary schools, guidance counsellors support students in the development of their IPPs and sit on the Career/Life Planning Program Advisory Committees required in the Creating Pathways policy.

Currently, only 34% of secondary schools have these advisory commit- tees, but where they exist, it appears that they do make a difference (or perhaps, the establishment of these committees reflects a school-wide commitment to career and life planning). There are several signs that the committees have an impact in schools:

- Schools with committees are far more likely to provide professional development to ensure teachers are knowledgeable about career planning: 67% of schools with committees provide professional development in this area vs. 30% where there is no committee.

- Schools with committees are more likely to report that all students are using the Individual Pathways Planning tool: in 64% of schools with committees, all students have IPPs vs. 52% of schools without.

- Schools without a committee are over twice as likely to report that no students are using the IPP (11% vs. 4%).

As in elementary schools, most secondary schools report only staff members on the committees, with fewer than 27% reporting representation from community members, parents, or students.

Opportunities to explore career paths

We have many local organizations and businesses who speak to students regarding careers in chosen fields as it is built into the curriculum.

Secondary principal, Rainbow DSB

While classroom learning is crucially important in developing communication, teamwork, and problem-solving skills, this learning is enriched when students have a chance for hands-on learning that takes them beyond the classroom. Over the past two years, these experiential learning opportunities have become more widespread in secondary schools.

Virtually every high school responding to our survey offers co-op courses, where students can learn in a workplace for credit. This type of work-based learning can expose students to employers’ expectations, and help them make stronger connections between school and their futures. A quarter of schools also provide opportunities for students to participate in internships.

Almost all secondary schools use school trips (96%) and support volunteer opportunities (92%) to expose students to experiences beyond the school walls.

In addition, employers and post-secondary institutions are often invited into schools to expose students to potential education and career destinations at post-secondary fairs (92% of secondary schools) or career days (57% of schools).

Young people in Canada are facing a world of rapid change. And there is growing agreement that their future wellbeing, and the wellbeing of society and our economy, will depend on their acquisition of founda- tional “human skills” and competencies (RBC, 2018; Schleicher, 2018).

Ontario’s career and life planning policy provides a potential roadmap to ensure that students – from kindergarten through to grade 12 – develop the vital competencies and self-understanding that will prepare them for long-term success, no matter what their destination.

However, there needs to be a more comprehensive and coherent approach to curriculum, resources, and course choices.

Recommendations

People for Education recommends that the provincial government:

- Develop a coherent strategy and consistent language that integrates foundational competencies for long-term success (e.g. People for Education, 2018) across the curriculum from kindergarten to grade 12, and in areas like the Creating Pathways policy, the learning skills on Ontario’s report cards, experiential learning programs, and the province’s 21st century competencies.

- Provide resources to support collaboration time and professional development for educators focused on integrating an inquiry-based approach to career and life planning across curriculum.

- Hold consultations with school administrators, and conduct research to understand the barriers to effective career and life planning in schools, and address those barriers.

- Clarify the roles of guidance counsellors, by evaluating both the range of education policies that includes them and the funding that leads to high student to staff ratios in Ontario’s schools.

- Ensure that parents and students have sufficient information about course choices in secondary school, including data on outcomes, graduation rates, and post-secondary access.

- Use the research from school boards that are combining grade 9 academic and applied courses to develop a strategy for eliminating applied courses in grade 9 by the fall of 2020, while continuing to ensure that students who need it receive required special education and other learning supports.

- Provide resources and supports to ensure that students can more easily transfer between courses throughout secondary school, so that no doors are closed too early, and so that developing adolescents can change their minds about their futures while they are still in high school.

Alberta Ministry of Education. (2016). Competencies: Descriptions, Indicators, and Examples. Edmonton, AB: Government of Alberta.

British Columbia Ministry of Education. (n.d.). BC’s New Curriculum. Government of British Columbia.

Brown, R. (2018). Getting through secondary school: The example of mathematics in recent TDSB grade 9 cohorts (Powerpoint presentation). Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario Access in Practice Conference. Toronto, ON: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario.

Brown, R.S. & Tam, G. (2017a). Grade 9 Cohort Graduation Patterns, 2011-16. Toronto, ON: Toronto District School Board.

Brown, R.S. & Tam, G. (2017b). Grade 9 Cohort Post-Secondary Pathways, 2011-16. Toronto, ON: Toronto District School Board.

Brooks, J. (1985) Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality. New Haven: CT, Yale University Press.

Curtis, B., Livingstone, D. W., and Smaller, H. (1992). Stacking the Deck: The Streaming of Working-Class Kids in Ontario Schools. Toronto, ON: Our Schools Our Selves Educational Foundation.

Davis, A. (2018, March 26). Grants for Student Needs (GSN) for 2018-19 (Memorandum to Directors of Education, Secretary/Treasurers of School Authorities). Toronto, ON: Government of Ontario.

Education Quality and Accountability Office. (2018). Ontario Student Achievement: Ontario’s Provincial Secondary School Report. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Grant, M. (2016). Aligning Skills Development With Labour Market Need. Ottawa, ON: The Conference Board of Canada.

Hanushek, E. and Woessmann, L. (2006). Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across Countries. Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society 116(510), 63-76.

Hattie, J. (2009), Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta- Analyses Relating to Achievement. London, England: Routledge.

James, C.E. & Turner, T. (2017). Towards Race Equity In Education: The Schooling of Black Students in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: York University.

Krahn, H. and Taylor, A. (2007). Streaming in the 10th grade in four Canadian provinces in 2000. Statistics Canada Catalogue

no. 81-004-XIE. Education Matters 4(2), 16-26.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2013). Creating Pathways to Success. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2016). Ontario Schools: Policy and Program Requirements, Kindergarten to Grade 12. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2013). PISA Results 2012: What Makes Schools Successful? Paris, France: OECD.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). Preparing our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World: The OECD PISA Global Competence Framework. Paris, France: OECD.

People for Education. (2015). Applied or Academic: High Impact Decisions for Ontario Students. Toronto, ON: People for Education.

People for Education. (2016). Measuring What Matters: Competencies in the Classroom. Toronto, ON: People for Education.

People for Education. (2017). Career and Life Planning in Schools: Multiple Paths; Multiple Policies; Multiple Challenges. Toronto, ON: People for Education.

People for Education. (2018). The New Basics for Public Education. Toronto, ON: People for Education.

Québec Ministry of Education. (n.d.). Chapter 2: Cross-Curricular Competencies. Québec City, QC: Government of Québec.

Robson, K., Anisef, P., Brown, R. S., & George, R. (2018). Under- represented students and the transition to post-secondary education: comparing two Toronto cohorts. Canadian Journal of Higher Education 48(1), 39–59.

Rodrigues, B. (2017, January 24). Changes to Implementation of Creating Pathways to Success and Community-Connected Experiential Learning (Memorandum to Directors of Education). Toronto, ON: Government of Ontario.

Rodrigues, B. (2018, August 24). Update: Education Funding for 2018-19 (Memorandum to Directors of Education, Secretary/Treasurers of School Authorities). Toronto, ON: Government of Ontario.

Royal Bank of Canada (RBC). (2018). Humans Wanted: How Canadian Youth Can Thrive in the Age of Disruption. Toronto, ON: RBC.

Schleicher, A. (2018). World Class: How to Build a 21st-Century School System, Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Toronto District School Board. (2018). Helping All Students Succeed: Director’s Response to the Enhancing Equity Task Force Report. Toronto, ON: Toronto District School Board.

Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and quoted material in this report originate from People for Education’s Annual Ontario School Survey, the 23rd annual survey of elementary and 20th annual survey of secondary schools conducted in 2018/19. Surveys were emailed to principals in every publicly funded school in Ontario in the fall of 2018. Surveys could be completed online via Survey Monkey in both English and French.

This year, we received 1,254 responses from elementary and secondary schools in 70 of Ontario’s 72 publicly funded school boards, representing 26% of the province’s publicly funded schools. Survey responses are also disaggregated to examine survey representation across provincial regions. Regional representation in this year’s survey corresponds relatively well with the regional distribution of Ontario’s schools.

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using inductive analysis. Researchers read responses and coded emergent themes in each set of data (i.e. the responses to each of the survey’s open-ended questions).

The quantitative analyses in this report are based on both descriptive and inferential statistics. The chief objective of the descriptive analyses is to present numerical information in an illuminating format that is accessible to a broad public readership. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software.

People for Education is an independent, non-partisan, charitable organization working to support and advance public education through research, policy, and public engagement.

Charitable No. 85719 0532 RR0001

728A St Clair Avenue West, Toronto, ON, M6C 1B3 416-534-0100 or 1-888-534-3944 www.peopleforeducation.ca

Notice of copyright and intellectual property

The Annual Ontario School Survey was developed by People for Education and the Metro Parent Network, in consultation with parents and parent groups across Ontario. People for Education owns the copyright on all intellectual property that is part of this project.

Use of any questions contained in the survey, or any of the intellectual property developed to support administration of the survey, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of People for Education.

Questions about the use of intellectual property should be addressed to the Research Program Director, People for Education, at 416-534-0100 or [email protected].

Data from the survey

Specific research data from the survey can be provided for a fee. Elementary school data have been collected since 1997, and secondary school data have been collected since 2000. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Author

Kelly Gallagher-Mackay

Document citation

People for Education (2019). Roadmaps and Roadblocks: Career and Life Planning, Guidance, and Streaming in Ontario’s Schools. Toronto, ON: People for Education.