People for Education's Annual report on Ontario’s publicly-funded schools is an audit of the education system – a way of keeping track of the impact of funding and policy choices in schools across the province. The report is based on survey responses from over 1100 principals in English, Catholic and French schools across the province.

School leadership

- Almost all schools (97%) have a full-time principal, but in elementary schools only 44% report having a vice-principal.

- Only 45% of elementary schools report having more than one office staff member.

- Principals most frequently report ‘managing employee and safe schools issues’ and ‘responding to system/Ministry initiatives and communications’ as the two areas in which they spend most of their time.

School staff and resources

- 8% of elementary schools and 6% of secondary schools report not having any library staff.

- 42% of elementary schools report they have a health and physical education teacher, representing a decline in the past three years.

- In schools with grades 7 and 8, 15% report having a specialist visual arts teacher and 10% report a specialist drama teacher.

First Nations, Métis and Inuit education

- 31% of secondary and 13% of elementary schools offer cultural support programs such as collaboration with a First Nation or Aboriginal community organizations.

- Only 29% of elementary schools and 47% of secondary schools offer professional development (PD) to staff on Aboriginal issues.

Fundraising and fees

- 99% of elementary schools and 78% of secondary schools report fundraising activities by parents, students, and staff.

- 47% of elementary schools fundraise for learning resources (e.g. classroom technology, online resources, and textbooks).

- The top 5% of secondary schools raised the same amount as the bottom 85% combined.

Special education

- An average of 17% of elementary and 23% of secondary students per school receive special education support.

- 57% of elementary and 53% of secondary principals report there are restrictions on waiting lists for special education assessments.

- 22% of elementary and 19% of secondary schools report that not all identified students are receiving recommended supports.

Support for French and English language learners

- In schools reporting English Language Learners, an average of 8% of elementary and 6% of secondary school students are ELLs.

- 80% of elementary schools and 69% of secondary schools in Ontario have a formal identification process for ELL/ELD students.

- 73% of elementary and 68% of secondary schools have students who are either English or French language learners.

Early childhood education and family support

- In schools with kindergarten, 72% report having on-site child care for kindergarten-aged children.

- Among the schools with on-site child care for kindergarten-aged children, 89% report on-site child care both before and after school.

- Only 36% of schools serving kindergarten-aged children indicate that they have a family support program.

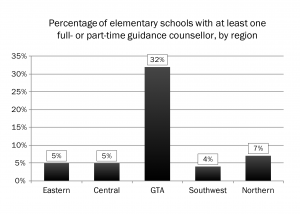

School guidance

- Only 14% of Ontario’s elementary schools report having at least one guidance counsellor.

- 99% of secondary schools have at least one guidance counsellor.

- The average ratio of students to guidance counsellors per secondary school is 391 to 1.

Streaming students

- 28% of Ontario’s grade 9 students (38,181) take applied mathematics.9

- Data from the Ministry of Education on course selections in 2014 show that 62% of students taking applied math were taking three or more applied courses, and that only 11% of students in applied math take no other applied courses.10

- Over the past five years, the percentage of students in applied English who passed the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test

In 2015:

- 84% of students now graduate in five years or less.1

- 72% of grade 3 and 6 students now meet the provincial standard (equivalent to a ‘B’ grade) in reading, writing and math, and more than 80% are proficient (‘C’).2

- Ontario was the only province in Canada to score above the Canadian average in reading, mathematics and science on the most recent Pan-Canadian assessment.3

- Ontario scored highest of all OECD countries on tests of computer literacy, which includes the ability to use computers to investigate, create and communicate in order to participate effectively at home, at school, in the workplace, and in society.

Ontario continues to have one of the most successful public education systems in the world when measured by graduation rates, reading, writing, math and science scores.

But is there more to education than graduation rates and scores in the 3 R’s?

The answer from education systems around the world is a resounding ‘yes’.

This year, Ontario’s Ministry of Education added student well-being as a fourth goal for Ontario’s education system, to go along with existing goals of student achievement, equity, and public confidence.5 Internationally, there is an increased focus on “soft” skills such as problem solving, critical thinking, and creativity.6

Locally, elementary and secondary schools increasingly report that they are monitoring students’ progress in areas such as health and well-being, social-emotional skills, and creativity.7 But…

While local school boards and schools might recognize the importance of broader skills and quality learning environments,8 they continue to be held accountable to the public and the Ministry of Education based on narrow measures of success in reading, writing and mathematics. Until broader goals are concretely defined and broader measures of success are identified and implemented, boards and schools will continue to feel compelled to focus resources, time and support on “what counts.”

The gap between policy and reality

One of the themes that emerges from this year’s report is the disparity between the goals identified in Ontario’s policies and the availability of ‘on the ground’ resources to realize those goals.

As a society, we invest more than $20 billion per year on edu-cation to support 1.9 million students. But even that amount leaves the system facing scarcity in many areas. Adding student well-being as a goal for education, while laudable, must come with the resources to support it, and with careful consideration of how school success is being measured. Without these considerations, we may worsen the disparity between the goals in Ontario’s central policies and the actual resources available to meet the goals.

Students’ education—their acquisition of knowledge, their creative, social-emotional and citizenship skills, and their overall health and well-being—is supported by a wide range of staff, resources and programs in schools. Together, the people in schools—including classroom teachers and specialists, principals and vice-principals, itinerants and support staff, volunteers and community partners—create learning environments that give all students a chance for success.

School Leadership

This year, as in other years, most principals express great pride in their schools, but also report operating under challenging constraints.

We believe in and are passionate about our school, and when one of us succeeds, we all succeed. Our challenge is the size of the school related to the amount of support in the school. … For me, the success of our school has been a labour of love. This year the challenges seem to be tipped more heavily than the rewards.

Elementary school, Peel DSB

Almost all schools (97 percent) have a full-time principal, but in elementary schools:

- Only 44% report having a vice-principal, and only 20% of those are full-time.

- Only 45% report having more than one office staff.

Two recent Canadian studies found that principals have a strong desire to work as instructional leaders—focused on classroom learning experiences—but struggle to find time and space for this work. Principals spend much of their day attending to building maintenance, behaviour issues, staffing, and ongoing communication about policy and pro-grams, both locally and provincially.12

Faced with a time crunch, [principals] find themselves giving more attention to the managerial aspects of the job than to the educational ones, a situation that they regret but consider inevitable.

Alberta Teachers’ Association, Leadership for Learning 13

At the provincial level, the Ontario School Leadership Frame-work outlines school administrators’ roles, stating that they are responsible for managing the day-to-day logistics, communicating the school’s vision, modelling and creating school values, maintaining high quality social relations, and providing instructional feedback to teachers. Principals and vice-principals are also responsible for school improvement planning, healthy schools policy, and the new focus on stu-dents’ well-being.14

In this year’s survey, we asked principals where they felt they spent most of their time. By far, the most frequently chosen combination was ‘Managing employee and safe schools issues’ and ‘Responding to system/Ministry initiatives and communications’.15

Funding smaller schools

Enrolment in Ontario’s elementary and secondary schools has declined by more than 140,000 students since 2002/03.16

The decline in enrolment has an impact on funding, on the viability of small schools, and on school boards’ capacity to apply economies of scale to support the range of programs, services and resources that all students need.

This year, in an effort to reduce the provincial deficit, the Ministry of Education is applying pressure to school boards to eliminate so-called empty space.17 Boards will receive reduced “top up” funding, which was previously provided to cover maintenance and operating costs in schools that had enrolments below their Ministry-allotted capacity. The Declining Enrolment Grant, intended to allow boards to gradually adjust to the per-pupil amounts in the education funding formula, will be cut in half.

Approximately two-thirds of a school board’s revenue, including the majority of funding for special education, is based on enrolment. As enrolment declines, boards lose revenue, and it becomes difficult for boards with a high number of small schools to provide specialized programs, extracurricular activities, or specialist teachers, such as teacher-librarians for elementary schools.

School Libraries

The school library is essential to every long-term strategy for literacy, education, information provision and economic, social and cultural development…School libraries must have adequate and sustained funding for trained staff, materials, technologies and facilities.

FLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto18

Teacher-librarians can play a vital role in supporting collaboration and integrated cross-curricular/classroom learning projects.19 But not all schools have teacher-librarians, and many are part-time.

A 2006 study conducted by Queen’s University and People for Education found a relationship between higher scores on EQAO reading tests in grades 3 and 6 and having library staff. As important, the study found that in elementary schools with teacher-librarians, students were more likely to report that they liked to read and that they were good at reading.20

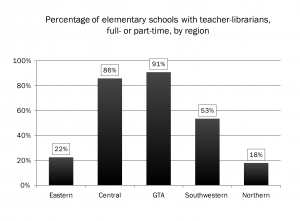

Over the last decade, the overall percentage of elementary schools with teacher-librarians either full- or part-time has stayed fairly consistent at approximately 60 percent, but the numbers have never returned to 80 percent, as reported in 1999.

Due to recently announced funding constraints, some boards have said they will be cutting elementary teacher-librarians completely.21 The percentage of secondary schools with teacher-librarians has declined from 78 percent in 1999/2000 to 72 percent in 2014/15.

elementary and secondary schools reporting library support |

elementary |

secondary |

||

| Teacher-librarian (full or part-time) | 60% | 72% | ||

| No teacher-librarian | 40% | 28% | ||

| A library technician (full or part-time) | 43% | 44% | ||

| No library staff at all | 8% | 6% | ||

Health and physical education

Ontario has extensive policy and curriculum that is focused on students’ mental and physical health. For example, the Ministry of Education’s Policy/Program Memorandum 138 outlines a comprehensive approach to student health, including areas such as healthy eating and physical activity. In elementary schools, the policy mandates 20 minutes of daily physical activity (DPA) within instructional time. In addition, Ontario’s comprehensive mental health strategy is shaped by key mental health principles such as diversity, equity, social justice, hope, respect and understanding.22

In November 2014, the province announced that it would work in partnership with Active at School, a coalition of private, public and not-for-profit organizations, and the Ontario Physical and Health Education Association (Ophea), to implement programs that will ensure that all young people get 60 minutes of physical activity per day.23

All of these strategies are supported by research that shows early exposure to comprehensive health programs has a positive impact on students’ short- and long-term health; may help to reduce the prevalence of chronic diseases in adulthood; and reduces the stigma attached to mental health problems.24

Despite the province’s extensive school health policies, there continue to be gaps “on the ground.” According to Ontario’s Auditor General, while DPA is intended to be mandatory in elementary schools, neither the Ministry nor school boards monitor schools to ensure that all students receive it. In her 2013 report, the Auditor said that teachers and principals cite a lack of time, a focus on literacy, and a lack of space as reasons that it is difficult to implement the DPA policy.25

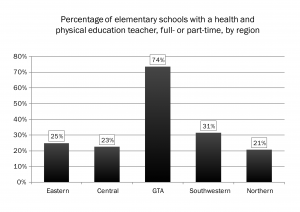

Specialist teachers have been shown to deliver more effective and consistent physical and health education programs than regular classroom teachers, and to provide the necessary leadership to build a health-promoting environment throughout the entire school community.26 However, there is insufficient funding to ensure that most students have access to specialist health and physical education teachers in elementary schools.

In 2015:

- 42% of elementary schools report that they have a health and physical education teacher; just over three-quarters of those are full-time.

- Only 21% of elementary schools in northern Ontario have a health and physical education teacher, compared to 74% in the GTA.

The Arts

Students’ exposure to arts education can build their capacity for imaginative, flexible and critical thinking—all foundational skills for living productive lives as adults.27

…distinctive forms of thinking needed to create artistically crafted work are relevant not only to what students do, they are relevant to virtually all aspects of what we do, from the design of curricula, to the practice of teaching, to the features of the environment in which students and teachers live.

Elliot Eisner, Stanford University28

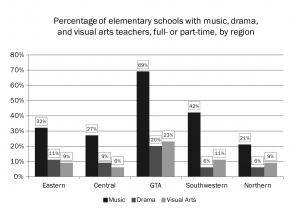

The majority of elementary schools in our survey do not have access to specialist arts teachers. This lack of access is particularly true in regions where the majority of schools are small.

- 45% of elementary schools report having a music teacher, either full- or part-time. This percentage has held relatively steady over the last ten years.

- Only 25% of elementary schools have a full-time music teacher.

Of schools with grades 7 and 8:

- 15% report having a specialist visual arts teacher.

- 10% have a specialist drama teacher.

Next steps

Ontario’s Ministry of Education has articulated a vision for education that includes success in literacy and numeracy, high graduation rates, and goals for students’ well-being.29 It is vital that funding for education supports not only those goals, but also ensures that all students are supported to develop the broad skills and competencies they need for long-term success.

In 2015:

- 82% of Aboriginal students in Ontario attend provincially-funded schools.

- 96% of secondary schools and 92% of elementary schools have some Aboriginal students enrolled.30

- 69% of secondary schools offer students or staff Aboriginal education opportunities, compared to 61% last year.

- 39% of elementary schools offer students or staff Aboriginal education opportunities, compared to 34% last year.

- 31% of secondary and 13% of elementary schools offer cultural support programs such as collaboration with a First Nation or Aboriginal community organizations.

- Despite an identified gap in teachers’ knowledge and confidence teaching FNMI subject matter,31 only 29% of elementary schools and 47% of secondary schools offer professional development (PD) to staff on Aboriginal issues.

Ontario’s public education system has a critical role to play in ensuring that First Nations, Métis and Inuit (FNMI) students receive an excellent and culturally responsive education in schools where everyone has a chance to learn about their vibrant cultures and histories.

Ontario is home to more than one-fifth of Canada’s Aboriginal population, and the vast majority of FNMI students (82 percent) attend provincially funded schools.32

While there is a vital national focus on issues of equity and school quality in on-reserve education, it is also urgent to ensure that Ontario’s provincially funded schools are places of opportunity for Aboriginal students.

A provincial strategy for improvement

In 2007, the province introduced the First Nations Métis and Inuit Education Strategy and Framework,33 with a set of goals to be achieved by 2016:

- improve achievement among Aboriginal students;

- close the achievement gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students; and

- ensure all students have an understanding of Aboriginal cultures, experiences, and perspectives.

In 2012, Ontario’s Auditor General raised concerns that the framework lacked both a detailed implementation plan and specific goals and performance measures.34 This year, the provincial government released an implementation plan that includes a number of performance goals for:

- increasing the percentage of FNMI students who achieve the provincial standard on Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) literacy and numeracy tests and increasing graduation rates;

- increasing the the number of FNMI teaching and non-teaching staff;

- closing achievement gaps between indigenous and non-indigenous students;

- improving FNMI students’ self esteem by collaborating with other provincial ministries “to develop an integrated approach to support their health, including mental health, and well-being”;

- increasing collaboration between school boards and First Nations communities;

- improving educators’ access to professional development; and

- building awareness among all students and educators about First Nations, Métis and Inuit issues, while building engagement with Aboriginal families and communities. 35

School boards have also created action plans for work with FNMI students and communities. Twenty seven boards are using the provincial Student Success Re-engagement strategy to support hiring educators with FNMI sensitivity and community knowledge. As part of the strategy, these educators reach out to FNMI students who have left school. In 2013/14, while only 456 FNMI students were contacted, more than double that number returned to school—an indication of the potential power of relationship-building and community connection within the work with FNMI communities.36

In her 2014 update, the Auditor General recognized the province had made significant strides in its Aboriginal education strategy and implementation planning. For example, more than 50 school boards now have First Nations, Métis and Inuit advisory councils. At the same time, she raised concerns that the implementation plan lacked detail and did not identify “obstacles faced by Aboriginal students or [outline] specific activities to overcome various obstacles.”37

A 2014 report from People for Education found that schools with a high proportion of Aboriginal students lag behind the rest of the province in access to staff that are strongly linked to student engagement, such as librarians, health and physical education teachers, and music teachers. Although these schools have a higher proportion of students with special education needs, they are less likely to have special education teachers, and less likely to have access to key professionals such as psychologists.38

Neither the FNMI strategy nor the implementation plan addresses the resource gaps that may present challenges to the successful implementation of the FNMI Framework.39

Opportunities for Aboriginal Education

Our survey data and comments show a growing number of schools doing powerful work to support Aboriginal students and to support learning about FNMI cultures. However, while the percentage of schools offering a range of programs has grown, the majority of elementary schools (61%) do not offer any Aboriginal education opportunities.

We have a vibrant Aboriginal community here … that supports us in this endeavour. There is still discrimination evident among some of our community members who are resentful of the work that we do at our school towards Aboriginal awareness. 53% of our students are self-identified First Nation: mostly Algonquin and Métis.

Elementary school, Nipissing-Parry Sound CDSB

We don’t have any children who have identified as FNMI. We have, however, worked to ensure the voice of First Nations, Métis and Inuit culture is present and visible in our school. We have had students and staff do work around the Seven Grandfathers and have used that as a part of our re-visioning process for our school. We have also had an FNMI artist come in and work with our students to make that vision visible in our school. We have supported staff to access FNMI learning opportunities offered by our board. We continue to work on building this into our programming.

Elementary school, York Region DSB

Professional learning for teachers

Over the past decade, the province and school boards have worked steadily to integrate Aboriginal perspectives and experiences across the K–12 curriculum. To deliver this curriculum effectively, teachers need to be comfortable with teaching FNMI material. However, according to the province, and teachers themselves, many are unprepared or uncomfortable teaching Aboriginal education topics.40 Professional development can be crucial to improving both school competencies and teacher capacity in this area.

Despite the potential benefits of professional development, only 47 percent of secondary and 29 percent of elementary schools report that they offer professional development around First Nations, Métis and Inuit issues.

We have Aboriginal students who attend our school from a neighbouring Reserve. Teachers are often afraid to teach cultural issues due to lack of information or familiarity with cultural ways. We try and engage Elders and teachers from the reserve, but we don’t have a lot of success getting them to come to school.

Elementary school, Superior North CDSB

In places where professional development is offered, there are examples of outstanding work. In one large-scale effort, 22 school boards with high percentages of Aboriginal students developed an extended Collaborative Inquiry project. The project involved board staff, principals and teachers working with community members and elders. Boards reported that, as a result of the project, teachers are now more comfortable teaching FNMI content and exploring indigenous teaching approaches, and there are stronger relationships between the schools and local First Nations communities.41

Native studies and Native Language Programs

Over the last two years, there has been a significant increase in the percentage of schools offering a Native Studies pro-gram. The program is often interdisciplinary, and provides an in-depth chance to explore Aboriginal cultures, the history of colonialism, and current issues.

- 47% of Ontario secondary schools now offer Native Studies programs, compared to 40% last year.

- 11% of secondary schools, and 4% of elementary schools offer Native language programs.

We have a 0.5 FTE Native Studies and Language teacher at our school who teaches students about Ojibwe culture and language. She incorporates traditional drumming, guest speakers, etc., into her program, but also adds the First Nations culture and language to our school-wide programs (i.e., character education program). We also have the exciting privilege of having our local Chief and Council provide funding for an EA to support the students from the reserve while at school. This is a very exciting opportunity for our students.

Elementary school, Near North DSB

Cultural support programs

In more and more schools—especially in northern Ontario— cultural support programs provide a mix of support and cultural enrichment to all students, and particularly help support the well-being of Aboriginal students.

- 31% of secondary schools and 13% of elementary schools have a cultural support program.

- 27% of secondary and 10% of elementary schools report they consult with local communities on policies and programming around FNMI issues.

HUGE successes…. over 30 students involved in our weekly cultural support program, elders involved, tutors involved, ceremonies and cultural teachings.

Secondary school, Near North DSB

According to the principals who provided comments, cultural support programs can involve a range of activities, including nutrition programs, tutoring and mentoring, “land-based programs,” traditional skills development, and counselling.

A number of schools report having a particular space in the school with a focus on Aboriginal culture—a classroom, an office or resource centre, or a garden.

The Bi’waase’aa program with an Aboriginal worker runs an after school program, works individually with students during the day, runs a Little Eagle program for 8 students 3 times a year, and runs a snack/lunch program.

Elementary school, Lakehead DSB

Making First Nations, Métis and Inuit culture visible in public schools: speakers, ceremonies and employment

Many schools ensure that students have access to First Nations, Métis and Inuit perspectives through guest speakers and ceremonies, pow-wows, events tied to Aboriginal aware-ness month or National Aboriginal Day, drumming groups, and artist residencies.

- 45% of secondary schools and 20% of elementary schools report having guest speakers.

- 20% of secondary schools and 8% of elementary schools report hosting ceremonies.

In 2007, the FNMI Policy Framework called for a “significant increase in the number of First Nations, Métis and Inuit teaching and non-teaching staff in Ontario school boards.” This goal was echoed last year in the Ontario Public School Boards’ Charter of Commitment on First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education. It continues to be difficult to track progress in this area because there are no provincial guidelines for staff self-identification. As a very small first step, this year the province introduced a tool to help assess boards’ progress on developing Aboriginal Staff Self-Identification policies.

Improving self-identification levels—and building support for Aboriginal education

In order to focus resources, understand levels of need, and assess achievement, it is vital to have accurate information about the number of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit students in provincially funded schools. This information can only be accessed when students self-identify.42

All boards have a voluntary, confidential self-identification policy. Last year, the province reported that, compared to census estimates, only 44 percent of Aboriginal students had self-identified to their schools—a figure that has increased dramatically in five years but is still very low.43

Some boards, through very active efforts, have been able to achieve high levels of self-identification. In the Lakehead DSB, for example, over 20 percent of the total student population have self-identified as Aboriginal—above census estimates of 15 percent.44

In their survey responses, many principals point to self-identification as a major challenge. Amongst other things, principals mentioned that the historical significance of self identification, and challenges in building trust amongst community members, elders, and parents as challenges to getting student to self-identify.

Next steps

Ontario has made great strides in both its Aboriginal education policy and in real change “on the ground” in schools. To ensure real and long-lasting change, more needs to be done:

-

the province should continue to work in partnership with First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities to develop broader measures of success beyond EQAO scores;

-

all teachers—new and current—should be provided with the background and understanding they need to deliver strong curricula and programs focused on Aboriginal history, culture and knowledge; and

-

the province should support the development of resources and practices to foster greater connections between families and schools.

Discrimination, trust, and historical legacy all are critical obstacles to the success of Aboriginal students. They are also reasons why all students need opportunities to learn about Aboriginal cultures and ongoing experiences.

In 2015

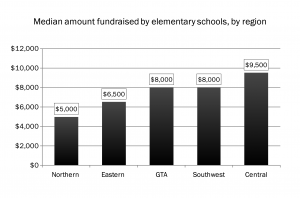

- 99% of elementary schools and 78% of secondary schools report fundraising activities by parents, students, and staff.

- Schools report raising from $0 to $250,000.

- 47% of elementary schools fundraise for learn-ing resources (e.g. classroom technology, online resources, and textbooks).

Many schools in Ontario rely on fundraising to support student enrichment and engagement, providing funds for field trips, learning materials, and athletics. This extra support can be particularly important for increasing opportunities for students to participate in extra-curricular activities, which are associated with student success and improved school climate.45

However, fundraising can also exacerbate gaps between schools in high- and low-income neighbourhoods.46

The fees that many schools charge for enrichment and experiential learning opportunities can also be a barrier to participation for some students.47

I couldn’t offer our enrichment and enhanced programs without these funds.

Elementary school, Upper Canada DSB

It’s challenging for a small school like mine with very limited abilities to raise [money] through fundraising. This can create very clear “have” and “have not” scenarios in our board with respect to things like playground equipment, sports equipment, and tech devices.

Elementary school, Kawartha Pine Ridge DSB

In 2012, Ontario’s Ministry of Education released guide-lines for both fundraising and fees to address some of these issues.48 Although the guidelines sought to respond to concerns about fundraising and fees, the stipulations in the guidelines remain broad and, in several instances, are subject to varying interpretation.

Fundraising

Ministry fundraising guidelines allow fundraising for “Supplies, equipment or services that complement items funded by provincial grants (for example, extracurricular band equipment, audio-visual equipment),” as well as things such as field trips, guest speakers, and scholarships. Schools may also fundraise for upgrades to sporting facilities, schoolyard improvements, and infrastructure improvements as long as they don’t increase the size of the school and are not already funded by provincial grants.

Under the guidelines, it is unacceptable to fundraise for classroom learning materials and textbooks, or for facility renewal, maintenance, or upgrades that are currently funded through provincial grants.49

It is clear from the results in this year’s survey that provincial guidelines are loosely followed:

- 47% of elementary schools report fundraising for learning resources. Among those schools:

- 94% fundraise for technology resources;

- 25% fundraise for online resources; and

- 12% fundraise for textbooks.

Wide gaps may create wide inequities

The range in the total amounts raised is very wide, from $0 to $250,000. The top 10 percent of elementary schools raised the same amount as the bottom 69 percent combined. The top 5 percent of secondary schools raised the same amount as the bottom 85 percent combined. There are also regional differences in funds raised.

Our families (over 70%) live in government subsidized housing. Our ability to fundraise is negligible. Our school has no playground equipment.

Elementary school, Kawartha Pine Ridge DSB

Fees

Ontario’s Education Act states that “A person has the right, without payment of a fee, to attend a school … in which the person is qualified to be a resident pupil.”50

Although this right is largely upheld in Ontario’s schools, there are a number ways that students may pay fees indirectly:

- 93% of elementary schools report asking parents for fees for field trips.

- 61% of elementary schools report asking parents for fees for extracurricular activities.

- 78% of secondary schools report having athletics fees, which range from $5 to $1,200.

- 91% of secondary schools report having a student activity fee. The fees range from $5 to $110.

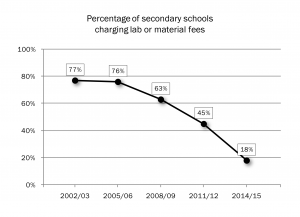

Some schools also charge fees for course-related materials, but that number has declined steadily since the Ministry introduced clearer guidelines that restrict charging fees for core materials necessary to teach the curriculum.51

Approximately 98 percent of schools report that they either subsidize or waive fees for students that cannot pay. In previous reports, People for Education found that school councils often fundraise to help cover costs for sports or field trips. In some cases, those funds are used to cover the costs for students whose families cannot afford to pay.52

We are lucky to have a very involved parent group, for a school of this size. Parents have fundraised for tech equipment (SMARTboards and iPads), yard improvement (playground equipment, track grading) and subsidized busing for major trips to bring the cost of the busing down for parents.

Elementary school, Hastings and Prince Edward DSB

Next steps

Ontario has a renewed vision for education that includes policy goals for students’ academic achievement and their well-being. If we are to realize this broader vision for success, it is vital to recognize that education is about more than just what goes on inside the classroom. The quality of the learning environment has an impact on students’ chances for success. When schools rely on fundraising and fees to support those learning environments, it creates inequities in the system. It is time for policy that clearly and concretely articulates what should be present in all schools to ensure that all students have access to the education, the supports, and the learning environments that they need and deserve.

In 2015:

- An average of 17% of elementary and 23% of secondary students per school receive special education support.

- 57% of elementary and 53% of secondary principals report there are restrictions on waiting lists for special education assessments.

- 22% of elementary and 19% of secondary schools report that not all identified students are receiving recommended supports.

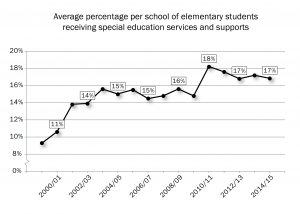

On average, 17 percent of elementary and 23 percent of secondary students per school (over 331,000 students) receive special education services and supports. This proportion has risen fairly steadily over the past 15 years.

Students’ special education needs vary widely, from minor accommodations, such as additional time to take tests or use of a laptop; to students who need significant help to communicate or be part of life in the school.

Substantial differences across school boards

There is little consistency across the province in how special education services are delivered. The percentage of students receiving special education supports ranges from 6 percent in some boards to 27 percent in others.53

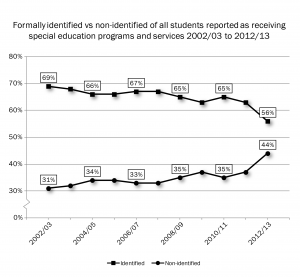

There are also significant differences between boards in how students access special education services. The Ministry of Education reports that, province-wide, 56 percent of students who receive special education support go through a formal Identification, Placement and Review Committee (IPRC) pro-cess, usually involving a psycho-educational assessment. That formal process gives students a legal right to special education support. The remaining students receive services without a formal process, usually through consultation with an in-school team to develop an Individual Education Plan (IEP).

Here again though, there are substantial differences between boards. In some boards, as few as 2 percent of students receiving special education supports have an IPRC, while in others, all students do.

Provincially, the percentage of students who get special education services less formally increased by more than one-third between 2003 and 2013.54

Staff are doing the best they can and are creative in their response to student needs…positive response from whole staff to assisting/problem solving for students. Staff are responsive to and inclusive of parents in process. We are seeing a larger increase in non-IPRC students with IEPs, [which leads to] concerns about generating special education staff numbers to continue to support students well.

Secondary school, Toronto DSB

“Our major bottleneck”: Access to special education services and supports

In this year’s survey, a number of principals expressed con-cern about students getting timely access to special education services. There are approximately 44,000 elementary and secondary students on waiting lists for assessments, IPRC meetings, or for services.56

Getting students assessed is our major bottleneck to providing special education services.

Elementary school, Rainbow DSB

On average, six students per elementary school are waiting for special education assessments. This number may seem small, but there are also many students who may need support and cannot get on a waiting list. The percentage of principals who report restrictions on the number of students that they can place on waiting lists for assessments has jumped since we first asked the question in 2010/11—from 50 percent to 57 percent this year in elementary schools, and from 47 percent to 53 percent in secondary schools.

It is difficult and not often recommended to identify [students] until grade 3. Thus, our students in greatest need at times for intervention are not yet identified/ accessing services. Additionally, with only a few identifications per year, per school allotted, many students do not get identified until much later—contrary to best practice per research/early identification and intervention. We work hard to identify needs early on, and access community agency support, but more funding at this level would be helpful.

Elementary school, Northeastern CDSB

“Not enough support”

A number of principals report that students in their school are well-supported through “fantastic” special education departments and the support of the whole staff. Far more frequently, however, principals report there are shortcomings in available supports that they are concerned will have an impact on learning and safety at their schools.

Special education is completely underfunded and the criterion-based process for students to receive support is not inclusive and completely flawed. We need greater support staff in the way of academic support but also itinerant support for special needs kids without diagnosis, or awaiting medical diagnosis.

Elementary school, Peel DSB

Students who have gone through an IPRC have a right to special education services, but the school is not required to implement all of the recommendations. Currently, 22 percent of elementary schools and 19 percent of secondary schools report that at least some of their identified students are not receiving recommended supports.

Staff support

The ratio of special education students to special education teachers has increased steadily over the past decade.

In 2014/15, in schools reporting a special education teacher:

- the average ratio per elementary school is 37 special edu-cation students per special education teacher, compared to 34 students per teacher in 2003/04.

- the average ratio per secondary school is 79 special edu-cation students per special education teacher, compared to 58 per teacher in 2003/04.

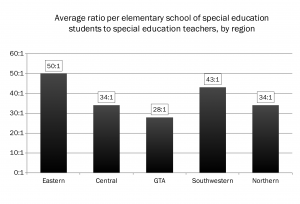

These ratios may also depend on where a student lives. On average, an elementary special education teacher in eastern Ontario works with nearly twice as many students per school as a special education teacher in the GTA: 50 vs. 28 students.

Educational assistants (EAs) can be a critical part of the special education team, providing important support to teachers and students. They often work closely with students who have the most intense special education needs. The majority of elementary schools (83 percent) have at least one full-time equivalent EA. Per school, the average number of students with special education needs for each EA is 21 in elementary schools and 57 in secondary.

The teaching assistant situation is at a critical and unsafe level. We absolutely do not have enough teaching assistants to serve our high needs students. Student safety is at risk. Mental health is becoming an increasing issue and there are very few available supports.

Elementary school, Peel DSB

Inclusion

According to provincial figures, 83 percent of students with special education needs are fully integrated into regular classrooms for at least half the day,57 a proportion that has increased slightly in the last decade, from 81 percent.58 In some boards, all students are included in regular classrooms, while in others, 4 percent (excluding gifted) may be in congregated settings.59

Because of the wide range in students’ needs, it is important that classroom teachers are skilled in using a variety of strategies to reach different learners, and that they have a team available to provide appropriate supports.60

Our inclusive model is one that more reflects society on the whole. I feel it is the only way to implement special education that helps prepare both students and their classmates for positive interaction and mutual support.

Elementary school, Simcoe Muskoka CDSB

Le ministère prône l’inclusion de tous mais ne fournit pas d’appui pour ces élèves. Il faut embaucher plus d’aide enseignantes et plus d’éducatrice pour venir appuyer les élèves en difficultés au sein des classes régulières. L’enseignant titulaire ne peut différencier au niveau que le ministère l’exige surtout avec un curric-ulum chargé et les classes ayant plus de 20 élèves.

Elementary school, CSDC de l’Est ontarien61

Changes in the funding formula

The majority of special education funding is provided on a straight per-pupil basis, and is intended to fund special education supports for students with relatively basic special education needs. But more than a third is earmarked to pro-vide services and/or support for the relatively small number of students whose special education needs are higher.

In 2014/15, the Ministry of Education maintained the overall level of funding for special education, but there have been major changes in how funding is distributed among boards. The changes have resulted in increased amounts for boards that were previously receiving relatively low funding for students with higher special education needs, and cuts to boards that had been funded at a higher level. The funding adjustments are being implemented over four years, but they are already adding stress to many boards’ budgets, since the vast majority of boards report that they spend significantly more on special education than they receive from the Ministry.62

The new funding model for students with higher special edu-cation needs is calculated based on two factors:

- a Special Education Statistical Prediction Model that uses demographic data to estimate the total number of students likely to receive special education supports; and

- a formula for ‘Measures of Variability’ which takes into account other particular local factors, such as percentage of students exempted from EQAO tests, remoteness, percentage of students currently receiving special education supports, estimated percentage of students who are First Nations, Métis or Inuit, and numbers of locally developed courses or alternative credits offered by the Board.

Unfortunately, most of the demographic statistics being used are now almost ten years out of date.63 This is worrying, because significant demographic changes should affect how the high needs special education funding is allocated.

Next steps

Special education support continues to be the most common concern raised by the principals who fill in our survey, the most common topic for parents who call the People for Education phone line, and one of the most common funding stresses raised by school boards.

Despite substantial increases in funding and changes to the funding formula, there continue to be major problems to be solved in special education.

Parents need special education ombudsman offices at the local level to help solve problems, and students with special education needs require stronger special education policy and easier access to resources to ensure their chances for success.

In 2015:

- 73% of elementary and 68% of secondary schools have students who are either English or French language learners.

- In schools reporting English Language Learners, an average of 8% of elementary and 6% of secondary school students are ELLs.

- In French-language elementary schools, an average of 17% of students per school are identified as French language learners.

- 80% of elementary schools and 69% of secondary schools in Ontario have a formal identification process for ELL/ELD students.

Ontario schools are home to students who speak more than 100 different languages and English-related dialects. These range from African, Asian, and European languages to Caribbean Creole and Jamaican Patois.64

Some students come to Ontario with strong literacy skills in their home language. For others (refugees in particular) this may be their first experience of school, or any form of literacy. The majority of Ontario schools—73 percent of elementary and 66 percent of secondary—have students who require language support.

Reaching proficiency in academic English language

There is a distinct difference between everyday English and academic English. Everyday English is required to hold conversations and navigate daily activities, and may only take one or two years to acquire. Academic English represents a deeper knowledge of the language that is used in school settings, and often takes more than five years to master.65

Formal support for English Language Learners (ELL) seeks to develop students’ proficiency in academic English. Students in English as a Second Language (ESL) programs have adequate literacy skills in their first language and only require language learning. English Literacy Development (ELD) programs cater to students whose first language is not English and who have limited literacy skills in any language. These students have often had limited formal schooling.66

Ministry of Education language policy points out that the success of ELLs is a school-wide responsibility. Schools that embrace diversity and inclusion not only help ELLs feel welcome and supported, but create a more enriching environment for all students.67

Most Ontario schools have English Language Learners

In the survey, 73 percent of elementary schools and 68 per-cent of secondary schools report they have ELLs.

In schools reporting English Language Learners, an average of 8% of elementary and 6% of secondary school students are ELLs.

Schools with 10 or more ELLs report an average ratio of 76 elementary ELL students per ESL teacher, and an average of 42 secondary ELL students per ESL teacher.

French language learners

Parents who were educated in French and those who immi-grated to Canada from French-speaking countries have a right to send their children to schools in Ontario’s French-language system. However, because many of these families live in predominantly English speaking communities, a large proportion of the students require French-language support.

In French language schools, this support is made available through Actualisation linguistique en français (ALF)/and the Programme d’appui aux nouveaux arrivants (PANA) curricula.

- On average, 17% of students in French language elementary schools are identified as French language learners.

- A large majority of French language elementary schools (85%) report having at least one ALF and/or PANA student.

- 62% of French language elementary schools report having an ALF/PANA teacher, and 26% have an itinerant.

Funding does not match need

Funding for ESL/ELD and ALF/PANA is not based on the number of students who need language support.68 Instead, funding is based on a formula calculated by using the number of immigrants from non-English or French-speaking countries who have been in Canada for four years or less, and the number of children whose language spoken most often at home is neither English nor French. ALF funding is based on the percentage of children requiring “assimilation” support.69

This method for allocating funds is not well-aligned with Ontario’s ELL policy, which states that school boards should provide students with the support they need to become proficient in English to the extent required to succeed in school.70 According to some school administrators, funding is insufficient to provide the instruction that students require to meet this goal.

The socio-economic needs of our school are great. While only 10% of our population are current ELL students, at least 30% [of ELLs in the school] are new Canadians whose first language is not English. We are also an inner-city school with the typical issues that students from that demographic face (eg. poverty, low education of parents, family instability, etc.).

Secondary school, Algoma DSB

Next steps

Ontario has well-articulated and ambitious policy for English and French language learners. The policy is intended to support students so that they will be able to “develop their talents, meet their goals, and acquire the knowledge and skills they will need to achieve personal success and to participate in, and contribute to, Ontario society.”71

Unfortunately, Ontario’s funding model does not match its policy goals.

For families and students struggling with a combination of language, economic, and settlement issues, four years of funding for language support may be insufficient. To ensure that Ontario’s policy supports the reality on the ground, it may be time to re-evaluate the funding model so that it provides support until language goals are met, and so that it is integrated with community supports for families.

In 2015:

- Among elementary schools with kindergarten-aged children, 64% have before and after-school care for kindergarten-aged students.

- Only 41% of schools with kindergarten report having on-site child care year-round.

In the last five years, the Ontario government has shifted the responsibility of early childhood education and family support to the Ministry of Education.

The Early Years Division now includes kindergarten pro-grams, extended day programs, licensed child care, parenting and family literacy programs, programs for children with special needs, and other family support programs. This policy decision recognizes the importance of the early years and their link to life long learning.

During early childhood, the brain develops at a rapid rate. The experiences and learning environments that a child is exposed to at this time are linked to cognitive, social, and emotional development.72 Decades of studies have shown that early childhood developmental processes can predict later life outcomes.73

Consequently, supports and resources in early years can be critical. Investments in high-quality early years programs are among the most effective, leading to more equitable education outcomes.74

Ontario’s government has recognized the importance of early childhood programs75 and has made notable strides in improving access to childcare and early childhood education in recent years. Research has demonstrated that children who attend Ontario’s full-day kindergarten program are better prepared for grade 1, and exhibit higher outcomes in the areas of social competence, communication skills, and cognitive development.76

Access to Integrated Child Care

A number of new provincial policies have also sought to improve the coordination of early learning and child care, to ensure “seamless and integrated provision of child care and education programs and services.” Provincial policy mandates that school boards must provide before- and after-school programs for kindergarten students at schools where “there is interest from the families of at least 20 children.”77

Having a childcare centre in the school is wonderful! It is a much easier transition for students coming into the junior kindergarten program. It is also great for children in the older grades who go to the before- and after-school programs as they can simply go down the hall rather than having to go to childcare outside of the building. From a school perspective, this is definitely preferable as we are not worrying whether a child has got to their childcare safely.

Elementary school, Bluewater DSB

In this year’s survey, we looked at the availability of on-site child care now that Ontario has fully implemented the full-day kindergarten program.

In schools with kindergarten, 72 percent report having on-site child care for kindergarten-aged children, representing a steady increase from 2011/12.

Among the schools with on-site child care for kindergarten-aged children:

- 90% report on-site child care before school.

- 94% report on-site child care after school.

- 89% report on-site child care both before and after school.

- 41% report on-site child care year-round.

For schools with grades 1–6, 70 percent of schools report having child care. Of these schools,

- 87% report having child care before school.

- 95% report having child care after school.

- 38% report having child care year round.

Seamless and integrated—promising practices

School boards that directly offer before and after school pro-grams are able to accommodate all families that request the program. They are not limited by space and program restrictions. This alleviates stress for families and reduces administrative challenges for school principals.78

Strong leadership and a commitment to early learning in the Waterloo Region and the Ottawa-Carleton District School Boards have increased access to high quality programming and on-site child care for thousands of families.79 Both boards provide successful examples of integrated and seam-less early learning programs for students.

In the Waterloo Board, extended day programs are now offered in 80 out of 87 schools, providing programs to over 4000 children between kindergarten and grade 3. Older children attend Youth Development Programs offered by Conestoga College and other community partners. In the Ottawa Board, 6000 children attend before- and after-school programs in over 100 schools.

Challenges to implementation

The growth in the availability of on-site child care is encour-aging, and suggests considerable progress throughout the province. However, a number of obstacles have persisted. In rural areas, for example, schools may face challenges finding child care providers or trained staff to operate before- or after-school programs.

Only one provider was available to offer [child care] in our area, and they declined due to being unable to find employees to run the program in a rural area.

Elementary school, Upper Canada DSB

Always very challenging to share classroom space. Teachers find it invades their preparation time at beginning and end of the day. We use every square inch of space.

Elementary school, Avon Maitland DSB

In this year’s survey, the challenges that schools commented on most frequently related to space limitations. Space constraints in some schools seem to be negatively influencing the seamless integration of school and care.80

To resolve these problems, some schools have begun to purchase portable facilities, construct new facilities, and partner with local community groups to use their space.

Sharing space is a challenge, but we have excellent communication and collaboration. Our board is now offering support through some shared [professional development] around our Early Years Strategy—very helpful in promoting shared space and shared resources.

Elementary school, Toronto DSB

Family Support Programs

The province allocates $90 million per year to support “universally accessible programs, services, and resources in easily accessible locations.”81 These programs are organized under Best Start Child and Family Resource Centres and include programs such as Ontario Early Years Centres, Child Care/ Family Resource Centres, and Parenting and Family Literacy Centres.82 In its report to the Ministry of Education, the Ontario Early Years Centre Provincial Network stressed the critical importance of an integrated system involving seam-less transitions among family support programs, child care, and school.83

In this year’s survey, however, only 36 percent of schools serving kindergarten-aged children indicate that they have a family support program.

Next steps

Ontario has made great strides in improving access to early childhood education and care. However, the integration of early learning supports across the system is a key objective in Ontario’s early learning policy, and that goal has not yet been realized. To ensure that all families have access to quality early childhood supports and services, and to ensure that Ontario has a truly seamless model for early childhood learning and care, it is vital to address challenges pertaining to access and integration of on-site programs.

In 2015:

- Only 14% of Ontario’s elementary schools have at least one guidance counsellor, and in these schools, only 10% are full-time.

- 99% of secondary schools have at least one guidance counsellor. Of these schools, 88% are full-time.

- The average ratio of students to guidance counsellors per secondary school is 391 to 1.

Ontario’s Pupil Foundation grant provides funding for one elementary guidance counsellor for every 5,000 elementary school students. For secondary schools, the province provides funding for one guidance counsellor for every 384 students.

The funding formula states that, “Guidance teachers at the elementary level are those providing guidance primarily to Grade 7 and 8 pupils.”

In 2013, the Ministry of Education introduced a comprehensive approach to career and life planning: Creating Pathways to Success. The policy requires elementary schools to have a process for documenting student learning and career and life planning from kindergarten through grade 12.84 The process includes reviews with teachers, guidance counsellors and parents.85 In addition, Creating Pathways to Success describes a strategy to enhance collaboration between school guidance staff, support staff, and other community stakeholders.

Access to guidance in elementary schools

Creating Pathways to Success identifies guidance counsellors as having a “strategic role” in ensuring the success of career and life planning.86 However, in this year’s survey, only 14 percent of Ontario’s elementary schools report having a guidance counsellor, and among that small minority, only 10 percent have counsellors that are full-time.

In grades 7 and 8, students make important decisions about secondary school course selection, and often face a range of issues related to adolescence.87 Because guidance counsellors can interact with students regularly, they have the opportunity to get to know individual students over time, and can provide effective one-on-one support. But only 20 percent of schools with grades 7 and 8 report having guidance counsellors, and the vast majority of these counsellors are part-time.

It would be wise if grade 8 teachers could communicate with high school principals or guidance. With such strict privacy issues, we have less communication of vital student data, especially for at-risk students/families.

Secondary school, Grand Erie DSB

Some schools attempt to increase access to guidance expertise by organizing visits and activities with high school guidance counsellors. However, it is unclear how systematic these links are, or how much they mitigate the effects of not having an elementary school guidance counsellor.

Guidance counsellors from the local high school visit twice a year with Grade 8 students to inform them about course selection. Grade 8 students also have the opportunity to spend a morning at the high school to experience what a typical day in high school is like. These practices support the transition to high school.

Elementary school, Simcoe Muskoka Catholic DSB

Regional Differences

Across the province, guidance counsellors are much more likely to be found in urban schools. This difference may be partly attributed to the provincial funding formula, which allocates the majority of funding to school boards based on the number of students enrolled.88 Greater Toronto Area (GTA) elementary schools are approximately 3 times more likely to have a guidance counsellor than other less densely populated regions of the province.

Secondary Schools

In contrast to elementary schools, secondary schools in the province are much more likely to have guidance counsellors:

- 99% of secondary schools report having at least one guidance counsellor; and in 88% of these, at least one counsellor is full-time.

- The average ratio of students to guidance counsellors is 391 to 1.

- Secondary schools report that the two areas where guidance counsellors spend most of their time are “supporting social-emotional health and well-being” and “supporting student development and refinement of their Individual Pathway Plans.”

Social Workers in schools

The government has aimed for greater integration of youth supports throughout the province.89 Social workers can be an important component of this support by serving students that require ongoing, intensive social-emotional support and helping to facilitate coordination between school guidance counsellors and external clinical professionals.

In schools where they are regularly scheduled, social workers have more opportunities to get to know school staff and students, and, consequently, to form collaborative relationships with school personnel.

- 75% of secondary schools have at least one regularly scheduled social worker, a steady improvement since 2002 when 46% of schools had them.

- 45% of elementary schools have at least one regularly scheduled social worker, a fairly steady improvement since 2002 when 35% had them.

- 16% of elementary schools in the province have no access to a social worker and no guidance counsellor.

- 28% of elementary schools in northern Ontario have no access to a social worker and no guidance counsellor.

Next steps

Students need a wide range of skills, information and support to realize their long-term goals. The Ministry of Education has developed ambitious policy that outlines how students should be supported to plan for the future, but there is a gap between the policy goals and the resources on the ground. The high ratios of students

to guidance counsellors in elementary and secondary schools make it difficult for staff to provide students with the one-on-one attention that they need to both support students’ well-being and help to ensure students can realize their goals for the future.

In 2015:

- 28% of Ontario’s grade 9 students (38,181) take applied mathematics.90

- 62% of students who take applied mathematics take3 or more applied courses.91

- In a Toronto DSB study, only 40% of students who took applied courses in grade 9 had graduated after five years, compared to 86% of students who took academic courses.92

Grade 8 is a critical year for Ontario’s students. It is not only a pivotal point in a young person’s emotional, social, and physical development,93 but also a time when students must choose between taking applied and academic courses in high school. These course selections largely determine students’ educational pathways throughout high school, and typically influence post-secondary options and career opportunities.94

Dividing students into separate tracks

Applied and academic courses were introduced in 1999 when the Ministry of Education implemented the Ontario Secondary Schools policy, Ontario Secondary Schools, Grades 9–12: Program and Diploma Requirements, 1999 (OSS:99)95. The new system established applied and academic courses in grades 9 and 10, which were prerequisites for a range of “destination-based” courses in grades 11 and 12.

The policy was intended to end streaming in Ontario secondary schools and create a system that kept “options open for all students.”96 In most cases, however, students in applied courses are in different classrooms, have different teachers, and experience a different curriculum.97 Data from the Ministry of Education on course selections in 2014 show that 62 percent of students taking applied math were taking three or more applied courses, and that only 11 percent of students in applied math take no other applied courses.98 Students are, in effect, grouped into separate tracks.

The association between applied courses and low-income students

The applied/academic system may perpetuate current economic and educational disparities among families.99

Demographic data from EQAO, along with 2006 Census data, show that schools with higher percentages of students from low-income families also have higher proportions of students in applied mathematics.100 A recent TDSB study found that only 6 percent of students from the highest income neighbourhoods took the majority of their courses as applied courses, compared to 33 percent of students from the lowest income neighbourhoods.101

In 2013, the OECD affirmed that separating students into groups produces lower outcomes for lower-income groups, especially when they are divided from their peers early in secondary school.102 The OECD has recommended that education systems should “avoid early tracking and defer student course selections until upper secondary.”103

The link between applied courses and widening achievement gaps

There is evidence that the current course selection system may be exacerbating achievement gaps in secondary school.

In 2013, EQAO reported a 40 percent gap in test performance between students in academic and applied courses. Over the past five years, the percentage of students in applied English who passed the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test declined from 62 percent to 51 percent.104

Applied courses were introduced in secondary schools a number of years ago to offer programming for students with different strengths, interests, needs and learning styles. Student achievement in these courses continues to lag. It’s worth reviewing the intent of these courses and how they might better support student achievement.

Bruce Rodrigues, CEO, EQAO105

The gap between success in applied and academic courses is also evident when students are followed from elementary to secondary school. Of the students who did not meet the standard in Grade 3 or in Grade 6, and took academic mathematics in grade 9, 47 percent met the standard on the EQAO Grade 9 academic mathematics assessment. The results were much different for students in applied mathematics: of the students who did not meet the standard in Grade 3 or in Grade 6, and took applied mathematics in grade 9, only 30 percent met the standard.106

Choosing a life pathway at a young age

Students in grade 8 are at an age when many “physical, social and emotional processes are in flux and formation.”107 Between early adolescence and graduation from secondary school, young people undergo many changes in interests, needs, and career aspirations. Requiring students as young as thirteen to make course choices may set some of them on pathways that will not align with the career and life goals that might emerge as they move through secondary school.

Grade 8 course selections also seem to conflict with the Ministry’s stated goals in its Creating Pathways to Success policy. The policy articulates the need to empower students and help them “respond to the realities of a complex, rapidly changing world;”108 however, students are expected to make decisions before they have any experience with secondary school life and the opportunities that are available to them.

Recent initiatives: success combining applied and academic

A small number of schools in Ontario have delayed early course selection by combining applied and academic courses in grade 9. In our annual report last year, we highlighted a program at the Granite Ridge Education Centre, a small K–12 school near Kingston, which successfully incorporated all applied math students into academic math. Notably, teachers reported improved student behavior and time on task in the grade 9 academic math class.109 After the change, 89 percent of Granite Ridge’s students writing the grade 9 math test achieved the provincial standard or higher, compared to the Limestone DSB at 82 percent, and the province at 84 percent.110

One of our most exciting statistics when we look at cohort data for the students that were in the [academic math] course last year (now in grade 10)— of our students that met the provincial standard in grade 9 academic math, 59% of them had not met the provincial standard in grade 6 math. So we saw a large percentage of these kids increase their numeracy skills.

Heather Highet, Granite Ridge Education Centre

The success of the initiative at Granite Ridge offers key insights and learning for potential province-wide efforts aimed at delaying secondary school course selections.

Next steps

Ontario’s education policy states that the system should keep “options open for all students.” The reality is that forcing students as young as 13 years old to choose between two paths through school closes many options. In particular, it may disadvantage our most vulnerable students. We strongly recommend delaying course decisions involving academic and applied courses to a later point in secondary school.

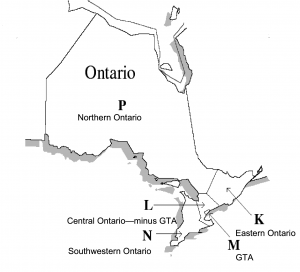

Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and quoted material in this report originate from People for Education’s 18th annual survey (2014/15) on school resources in Ontario’s elementary schools and 15th annual survey of school resources in Ontario’s secondary schools.

These surveys were mailed to principals in every publicly funded school in Ontario during the fall of 2014 (translated surveys were sent to French-language schools). Surveys were also available for completion online in English and French. All survey responses and data are confidential and stored in conjunction with Tri-Council recommendations for the safeguarding of data.111 The 2014/15 survey generated

1,196 responses from elementary and secondary schools. This figure equals 28% of the province’s schools. Of the province’s 72 school boards, 71 participated in the survey. The responses provide a representative sample of publicly funded schools in Ontario.

Survey representation by region

Region (sorted by postal code) |

% of schools in survey |

% of schools in Ontario |

| Eastern (K) | 19% | 18% |

| Central (L excluding GTA) | 11% | 17% |

| Southwest (N) | 23% | 20% |

| North (P) | 12% | 11% |

| GTA | 35% | 34% |

Data Analysis

The analyses in this report are based on both descriptive and inferential statistics. The descriptive statistical analyses were conducted in order to summarize and present numerical information in a manner that is comprehensible and illuminating. In instances where inferential statistical analyses are used, we examined associations between variables, using logistic regression analysis. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. For regional comparisons, schools were sorted by region using postal codes. The GTA region comprises all of the schools in Toronto together with schools located in the municipalities of Durham, Peel, Halton, and York.

Reporting

Calculations have been rounded to the nearest whole number and may not amount to 100%.

- Ministry of Education (2015) News Release: More Ontario Students Graduating High School Than Ever Before, Ontario Publishing Board-by-Board Rates to Help More Students Succeed, link: http://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2015/04/more-ontario-students-graduating-high-school-than-ever-before. html. Accessed, April 20, 2015.

- Ibid.

- EQAO (2013) Pan-Canadian Assessment Program (2013) , Ontario Report, link: http://www.eqao.com/pdf_e/14/PCAP-ontario-report-2013.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- EQAO (2013) International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) 2013 Overview of Ontario Results, link: http://www.eqao.com/ pdf_e/14/ICILS-ontario-report-2013.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- Schleicker, Andreas (2015) Skills Have Become Key to 21st Century Skills Societies, Key Note Address International Congress of School Effectiveness and Improvement, 28th Annual Conference, Cincinnati, Ohio, January 3-6. Link: http://www.icsei.net/conference2015/index.php?id=1757. Accessed April 28, 2015.

- Ministry of Education, Ontario (2014). Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision in Education in Ontario, Queen’s Printer, Ontario. Link: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/about/ pdf. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- Principals indicated in our survey that they measured progress in other areas of success besides reading, writing and mathematics. The following percentages represent what principals reported measuring for elementary and secondary schools: Secondary: creativity-34% of schools; citizenship-42% of schools; student health/well being-82% of schools; social-emotional learning-74% of schools. Elementary: creativity-32% of schools; citizenship-44% of schools; student health/well being-75% of schools; social-emotional learning-63% of schools.

- District School Board MISA Leads (personal email communication, February, 2015).

- Education Quality and Accountability Office. (2014). EQAO’s Provincial secondary school report: Results of the Grade 9 assessment of mathematics and the Ontario secondary school literacy test. Toronto: EQAO.

- Personal communication. Ontario Ministry of Education. Email dated March 13, 2015.

- Education Quality and Accountability Office. (2014). See note 9.

- Alberta Teachers Association. (2009) Leadership for learning: The experience of administration in Alberta schools. Link: http://www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/ Publications/Research/PD-86-14%20Leadership%20for%20 pdf. Accessed April 23, 2015. Pollock, K. (2014). The Changing Nature of Principals’ Work, Final Report (pp. 1–42). Ontario Principal Council. Link: http://www.edu.uwo.ca/faculty_profiles/cpels/pollock_ katina/OPC-Principals-Work-Report.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2015.

- Alberta Teachers Association. Ibid.

- Institute of Leadership. (2012). The Ontario Leadership Framework; A school and system leader’s guide to putting Ontario’s leadership framework into action (pp. 1–28). Ministry of Education, Ontario. Link: http://iel.immix.ca/ storage/6/1345688999/Final_User_Guide_EN.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2015.

- The top three combinations of work that the principals chose were: Managing employee and safe schools issues and Responding to system/ministry initiatives and communication (38%); Managing employee and safe schools issues and Direct student support (12%); Managing employee and safe schools issues and Improving the instructional program (11%).

- Ministry of Education, Ontario (2015) School Board Funding Projections for the 2015–16 School Year. Link: http://www. gov.on.ca/eng/funding/1516/2015FundingEN.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2015.

- Eisner, Elliot W. (2002) ‘What can education learn from the arts about the practice of education?’, the encyclopedia of informal education, http://www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_ arts_and_the_practice_or_education.htm. Accessed April 24, 2015.

- UNESCO/IFLA School Library Manifesto (n.d.). Link: http:// unesco.org/webworld/libraries/manifestos/school_ manifesto.html. Accessed April 25, 2015.

- Exemplary School Libraries in Ontario. Klinger, D.A.; Lee, E.A.; Stephenson, G.; Deluca, C.; Luu, K.; 2009.

- Ibid.

- Rushowy, K. (2015) Toronto Catholic board cuts include teacher-librarians: Job called key to literacy, love of reading, while also providing teacher support and resources. Link: http://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2015/03/25/toronto-catholic-board-cuts-include-teacher-librarians.html. Accessed April 30, 2015.

- Toronto public: Teacher-librarians in elementary and secondary schools.

- Ottawa Catholic: No teacher-librarians in elementary schools; larger schools have full-time library technicians, smaller schools part-time technicians. Every high school has a full-time teacher-librarian and library technician.

- Halton public: Elementary schools have a full- or part-time teacher librarian; high schools have a full-time teacher-librarian and full-time technician.

- Halton Catholic: Library technicians in elementary schools; librarians in high schools.