Implementation of de-streaming in Ontario hampered by lack of time and resources

Only 20% of Ontario high school principals say they have enough support to implement de-streaming for their Grade 9 students, a decline from 30% the year before. This is one of the results from People for Education’s 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey – based on responses from 1,044 principals from across all of Ontario’s 72 school boards. The findings also reveal a decline since last year in the proportion of schools reporting smaller class sizes and teacher professional development to support de-streaming.

There was a lot of information and support last year, but this year as the balance of the Grade 9 courses become de-streamed, there really seems to be nothing.

Secondary school principal, Northern Ontario

Ontario introduced de-streaming in grade 9 in 2021, after years of evidence showing that the policy systematically disadvantaged marginalized students, Black students, Indigenous students, and students from lower income families. However, findings from the 2022-23 AOSS suggest that not all the necessary planning and resources are in place to ensure the effective implementation of the policy.

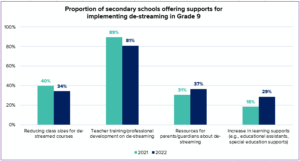

Fewer schools offering smaller class sizes and teacher training to support de-streaming

While the 2022-23 survey results show increases in the proportion of schools offering resources for parents and supports such as educational assistants, there have been decreases since 2021-22 in the proportion of schools reporting they are able to reduce class sizes (34%, down from 41%) and provide teacher professional development to support de-streaming (81% down from 89%).

Majority of principals say increased supports are needed for effective de-streaming

In their survey responses, principals said it was difficult for teachers to support struggling students without having access to smaller class sizes, and time and resources for both professional development and curriculum planning.

We are implementing de-streaming and core curriculum courses in Grade 9 to students coming out of a pandemic with the highest ever social/emotional needs, and teachers are exhausted with preparation or supports needed to make this an effective change.

Secondary school principal, GTA

In 2022-23:

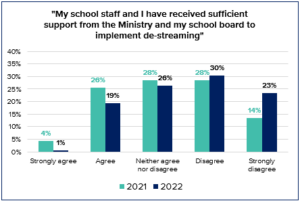

- 53% of principals disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “My school staff and I have received sufficient support from the Ministry and my school board to implement de-streaming” – an increase from 42% last year.

- 96% of secondary principals reported they needed an increase in learning supports, such as educational assistants and special education supports.

- 93% of secondary principals said they needed support to provide teacher training/professional development on de-streaming.

- 85% of secondary principals said they needed support to reduce class size.

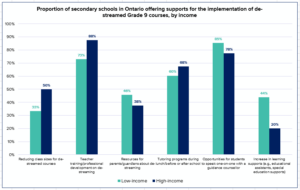

Neighbourhood income influences availability of some de-streaming supports

Findings from the survey also show that secondary schools in neighbourhoods with higher median family incomes were more likely to have de-streaming supports such as smaller class sizes, and teacher professional development. However, lower income neighbourhoods were more likely to have tutoring programs and increased learning supports such as educational assistants and special education supports.

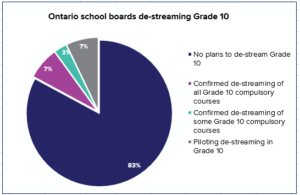

Few boards de-streaming Grade 10

While the province has de-streamed Grade 9 compulsory courses, no plan has been announced to de-stream Grade 10. As a result, students finishing Grade 9 in most school boards will be faced with deciding between academic and applied courses in Grade 10, which may result in a return to the inequities that existed with streaming in Grade 9, and a return to limiting students’ choices for the rest of high school and for their post-secondary pathways.

In the fall of 2023, People for Education conducted a scan of the 70 Ontario school boards with secondary schools to understand how many school boards were moving ahead with de-streaming Grade 10 despite the lack of provincial policy. The scan revealed that 12 school boards have begun the process of de-streaming Grade 10, with 5 planning to fully de-stream grade 10 and the others introducing de-streaming in stages.

Funding to support de-streaming

When de-streaming was first introduced, funding to support the change was rolled into the province’s new Math Strategy and the COVID-19 Learning Recovery Fund. For the 2023-24 school year, the province announced a $103 Million Supporting Student Potential Fund to cover the costs of additional teachers in Grades 7 through 10, provide supports for Grade 8 students transitioning to a de-streamed Grade 9 program; and supports for Grade 9 students in de-streamed classes.

It is not yet clear whether the funding announced for the 2023-24 school year will address ongoing challenges including supporting more schools to provide smaller class sizes, more special education support, and more time for teachers to engage in professional development.

Delays in access to new curriculum adds to pressure

The province introduced new de-streamed Grade 9 mathematics curriculum in 2021, followed by a new de-streamed Grade 9 science curriculum in 2022 and de-streamed Grade 9 English curriculum in fall of 2023. In all these cases, teachers were given access to the new curricula in late spring – just months before they had to implement it. For Grade 9 Geography and French, teachers have had to adapt existing academic curricula to make it work for the range of students in their de-streamed classes.

Several principals, in their responses to the survey, pointed to the late introduction of new curricula and the expectation of teachers to manage the adaptation of existing academic curricula as key challenges school staff are facing.

Delays in staff getting access to curriculum materials to design courses has been challenging. Limited time for staff to develop materials, and limited resources have been challenging for some departments.

Secondary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

Learning from the past

Streaming has been recognized as a problematic and discriminatory practice by experts ranging from the OECD in multiple reports to Bob Rae in a 1992 report on anti-racism written for the Ontario government. However, attempts at de-streaming in Ontario have historically failed. The primary causes of those failures appears to have been a lack of recognition of the how important it is to address systemic issues of racism and discrimination in children’s early years, a lack of comprehensive implementation plans, developed in collaboration with education stakeholders, as well as a lack of long-term commitment to providing the resources necessary to ensure that de-streaming is a success.

It is critical not to mistake the challenges arising from the implementation of de-streaming for justification not to move forward. De-streaming has demonstrated the potential to unlock improved equitable outcomes for historically marginalized students, but it cannot happen without the adequate policy, planning, and funding to support its long-term success

Recommendations for the future

People for Education has three overarching recommendations to ensure the effectiveness of de-streaming in Ontario:

- Plan in consultation with students, educators, education support staff, and families.

- People for Education continues to call on the province to convene an Education Task Force to provide advice on recovery and renewal post-pandemic, and on vital policy areas such as the implementation of de-streaming.

- Provide learning supports for de-streaming that meet schools’ diverse needs.

- De-streaming is a significant structural, pedagogical, and cultural change for schools and school boards. To support the introduction of full de-streaming, the province must provide sufficient and ongoing resources to support reduced class sizes, greater opportunities for professional development, accessible information for families, and additional staff.

- Monitor and evaluate implementation as frequently as possible.

- Simply de-streaming curriculum is not enough. The province must implement a comprehensive evaluation plan to ensure successful outcomes, in particular for the students who have been disproportionately disadvantaged by streaming in the past. The evaluation plan should be aligned with the new Board Improvement and Equity Plan, which mandates the collection of disaggregated demographic data to support school boards in tracking student achievement, equity, well-being, and transitions.