This report, based on survey responses from 1244 principals across Ontario, is an audit of the education system – a way of keeping track of the impact of funding and policy choices in schools across the province.

School administration

- 21% of elementary schools have at least one full-time vice-principal (VP) and 25% have a part-time VP.

- Only 9% of elementary and 13% of secondary principals rank supporting professional learning and improving the instructional program as the task they spend the most time on.

Guidance counsellors

- 20% of elementary and 26% of secondary schools report that the most time-consuming part of their guidance counsellor’s job is providing one-on-one counselling to students for mental health needs.

- Among secondary schools with guidance counsellors, the average ratio of students to guidance counsellors is 396:1. In 10% of schools, this average jumps to 826:1.

Special education

- An average of 17% of students per elementary school and 27% per secondary school receives special education support.

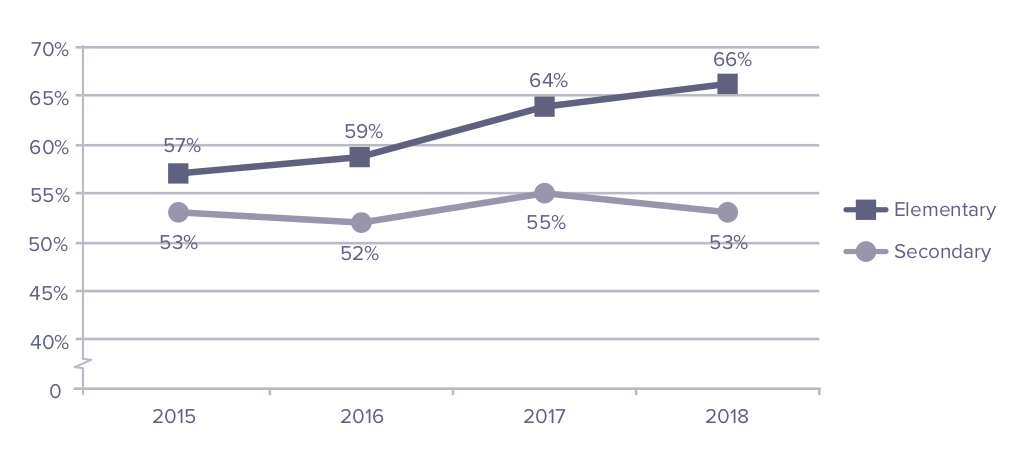

- 66% of elementary schools and 53% of secondary schools report a restriction on the number of students that can be assessed for special education each year—a trend that has been increasing among elementary school over the years.

- 92% of urban elementary schools have a full-time special education teacher, compared to 72% of rural elementary schools.

Indigenous education

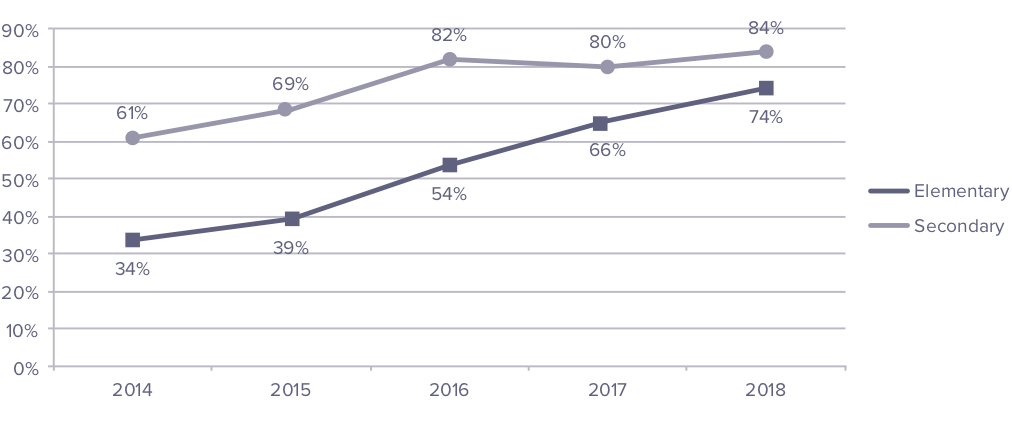

- 74% of elementary and 84% of secondary schools offer at least one Indigenous learning opportunity.

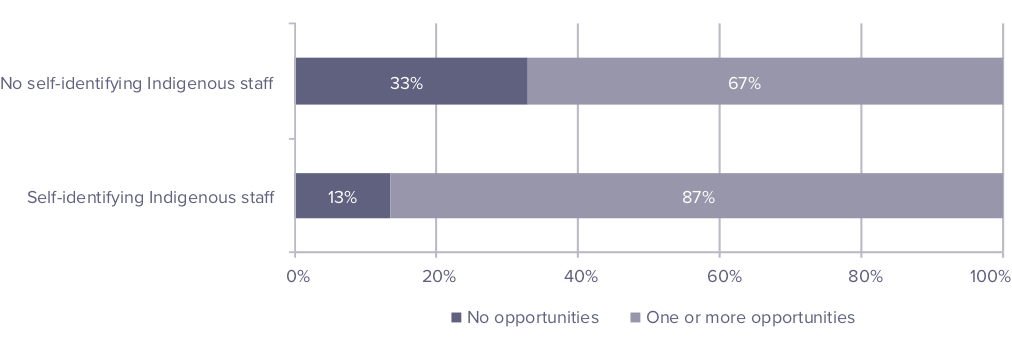

- 21% of elementary and 46% of secondary schools have at least one self-identified Indigenous person on staff.

- 87% of elementary schools with an Indigenous staff member have at least one Indigenous education opportunity, compared to 67% of schools without an Indigenous staff member.

Physical and mental health

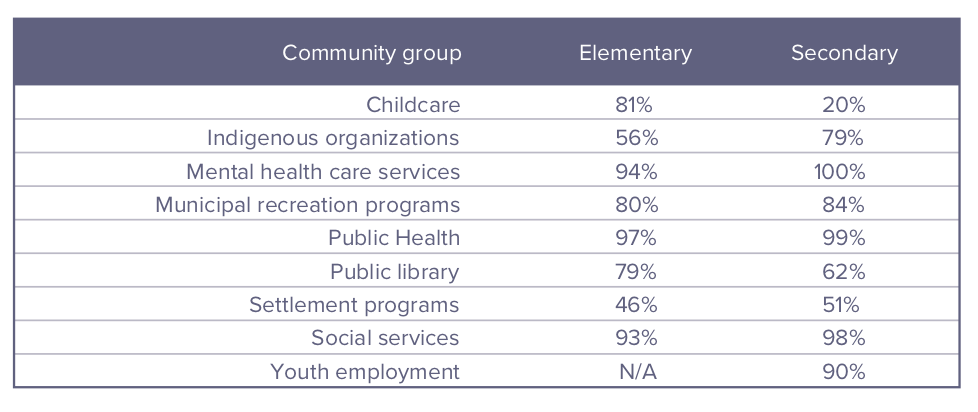

- 94% of elementary schools and 100% of secondary schools report collaborating with mental health care services.

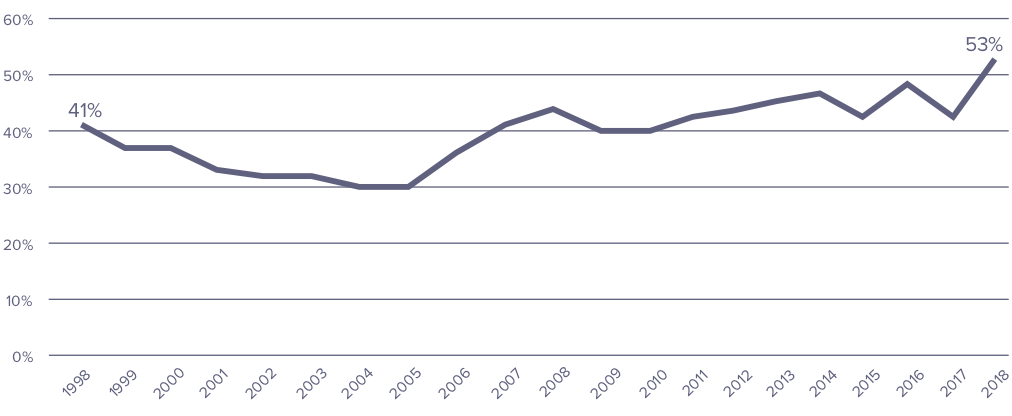

- 39% of elementary schools have a full-time health and physical education (H&PE) teacher, up from 18% in 1998.

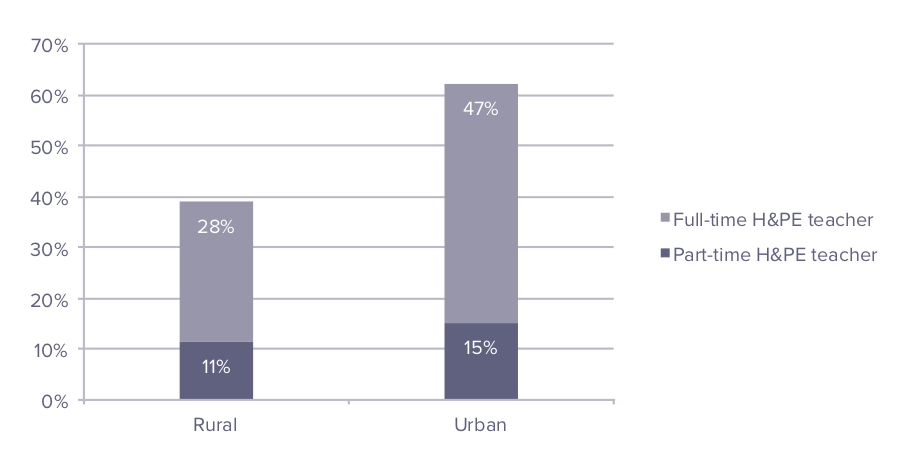

- 62% of urban elementary schools have H&PE teachers, compared to 39% of rural elementary schools.

Childcare

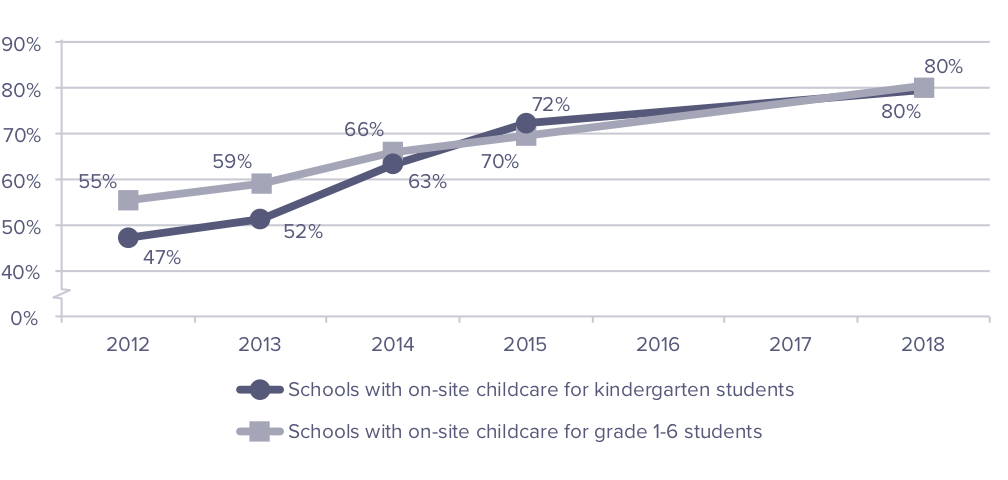

- Of the schools with kindergarten, the percentage reporting on-site childcare for kindergarten-aged children has increased from 47% in 2012 to 80% in 2018—an all-time high in the history of the survey.

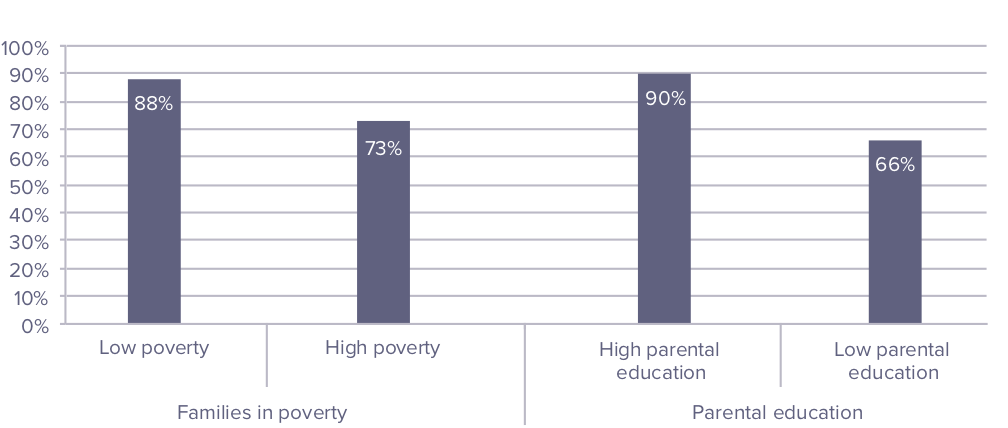

- 90% of elementary schools with a higher proportion of parents who have graduated from university offer childcare, compared to only 66% of schools with lower proportions of university-educated parents.

- The percentage of schools with Family Support Programs dropped from 36% in 2015, to 28% in 2018.

Arts education

- 46% of elementary schools report having a specialist music teacher, either full- or part-time, up from 41% last year.

- Elementary schools with higher proportions of parents who have graduated from university are twice as likely to have a specialist music teacher as schools with lower proportions.

Beyond the school walls: connecting to community supports

- 19% of elementary schools and 18% of secondary schools report that they have a staff member (other than the principal or vice-principal) acting as a community liaison, a drop from 20% and 34% respectively in 2011.

- Elementary schools in urban areas are more likely to have a community liaison than those in rural areas.

“Public education in Ontario can take a leading role in the international movement to target critical areas of student development, including health, citizenship, creativity, and social-emotional learning, but it will require a commitment to providing the required resources and policy to both support and integrate these vital areas of learning across the curriculum and in the day-to-day lives of schools. It will also require concrete commitments and resource allocations to ensure that all students—no matter what their family income, their parents’ education, their ethnicity or race, or where they live in the province—have access to a broad range of learning opportunities that provide an equitable chance for long-term success, in school and in life. These are the new basics for public education.”

People for Education

Ontario’s public education system is one of the most successful systems in the world. Whether measured by provincial, national, or international standards, and whether the assessment measures 15-year olds in science or 8-year olds in reading, Ontario’s public education system is doing very well in teaching students the basics.

In 2015, only six out of 72 jurisdictions ranked higher than Ontario on international assessments in science (EQAO, 2016). Results from the 2016 Pan-Canadian Assessment Program (PCAP) showed that 89% of Ontario’s grade 8 students performed at the expected proficiency for reading, and Ontario was the only province that performed above the Canadian average in both interpreting text and critically responding to text (CMEC, 2016). Provincially, over 90% of grade 3 and 6 students demonstrate required knowledge and skills in reading and writing (EQAO, 2017a), while over 90% of grade 3 and 79% of grade 6 students demonstrate the required knowledge and skills in mathematics (EQAO, 2017b).

By any large-scale performance measure of the basics, Ontario’s public education system is doing well. But what about the rest of what public education promises to deliver? Are we providing students with all of the resources and supports they need to thrive—now and into the future?

In response to this year’s Annual Ontario School Survey, principals told us that they love their jobs and their school communities, but that they also feel stretched—working long hours with limited resources to meet the needs of their students.

This year’s report is based on survey results from 1244 schools in 70 of Ontario’s 72 school boards. Three key issues emerged:

- Students’ mental health is a clear area of concern for schools. Principals note limited access to guidance counsellors, educational assistants, psychologists, and other mental health professionals, and express concern about their capacity to address growing mental health needs among students. While the newly revised health curriculum and Ontario’s Wellbeing Strategy are valuable resources to support students’ mental health, long-term change will require recognizing the benefits of mental health promotion, integrating social-emotional and health competencies across the curriculum, and providing adequate resources and capacity-building for staff to support both themselves and their students.

- Indigenous education is reaching new heights in building awareness and opportunities for all students to learn about Indigenous culture and history, but Indigenous students continue to struggle. To address the gaps for Indigenous students, it is time to work with Indigenous leaders and scholars to find new ways of defining school success beyond the 3R’s, and to integrate Indigenous perspectives on success—a balance between the intellectual, the physical, the emotional, and the spiritual—into the public education system.

- An analysis of information from Statistics Canada and Ontario’s Ministry of Education, alongside the survey results, shows that access to things like childcare and arts enrichment, is affected by where a student lives, their family’s income, and the education level of their parents. This gap must be addressed in order to ensure that all students have an equitable chance for success.

Public education in Ontario can take a leading role in the international movement to target critical areas of student development, including health, citizenship, creativity, and social-emotional learning, but it will require a commitment to providing the required resources and policy to both support and integrate these vital areas of learning across the curriculum and in the day-to-day lives of schools. It will also require concrete commitments and resource allocations to ensure that all students—no matter what their family income, their parents’ education, their ethnicity or race, or where they live in the province—have access to a broad range of learning opportunities that provide an equitable chance for long-term success, in school and in life. These are the new basics for public education.

In 2018:

-

21% of elementary schools have at least one full-time vice-principal (VP) and 25% have a part-time VP.

-

85% of secondary schools have at least one full-time VP and 8% have only a part- time VP.

-

50% of elementary schools in urban areas report having a vice-principal, full- or part- time, compared to 39% of those in rural areas.

-

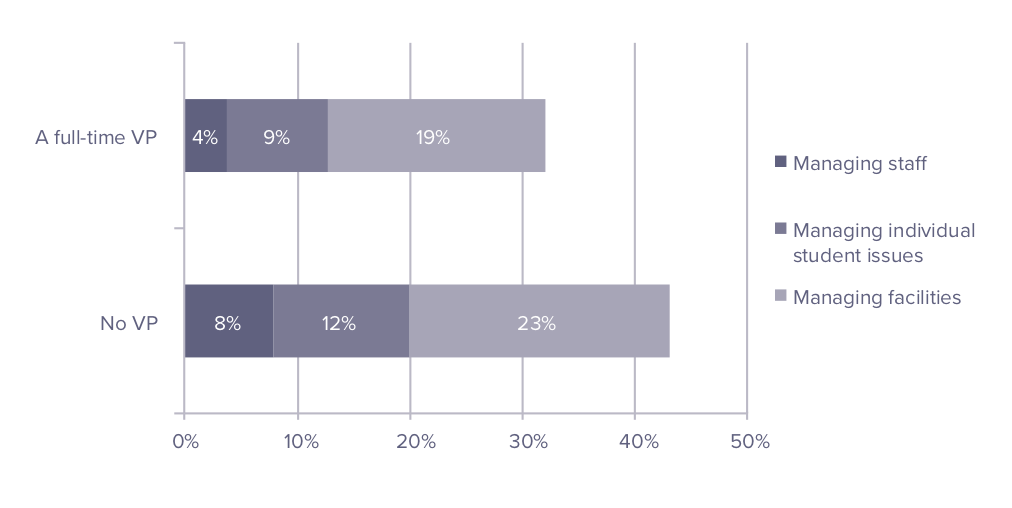

23% of elementary principals without a VP ranked managing facilities as their most time-consuming task, compared to 19% of those with a full-time VP.

-

7% of elementary principals rank managing staff as their most time-consuming task, compared to 27% of secondary principals.

-

Only 9% of elementary and 13% of secondary principals ranked supporting professional learning and improving the instructional program as the task they spend the most time on.

The principal’s role can be extremely challenging. They are expected to lead school improvement and instruction efforts, attend to individual student needs, support implementation of Ministry and school board initiatives, support special education programs and students, supervise staff and human resources, attend to school facilities, and communicate with parents and the community (Pollock, 2017; McCarthy, 2016).

Recent research from Western University found that principals in On- tario work an average of 59 hours per week (Pollock, 2014, p. 15), and vice-principals work an average of 55 hours (Pollock, 2017, p. 11).

Despite the many challenges, the principals responding to this year’s survey remain positive, commenting about helpful and collaborative staff, good community relations, and positive school climates.

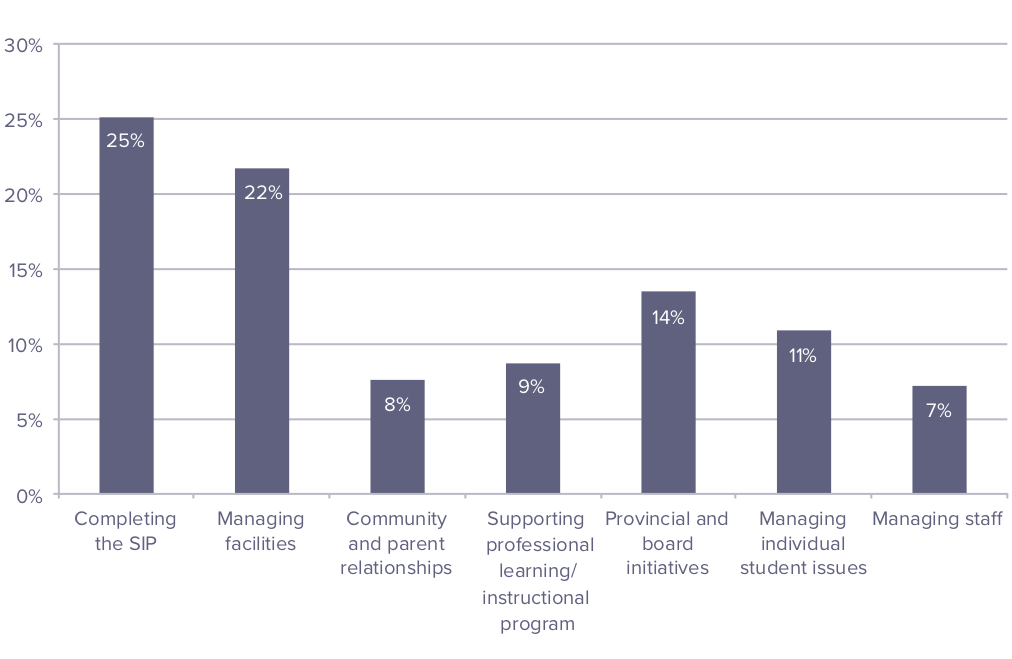

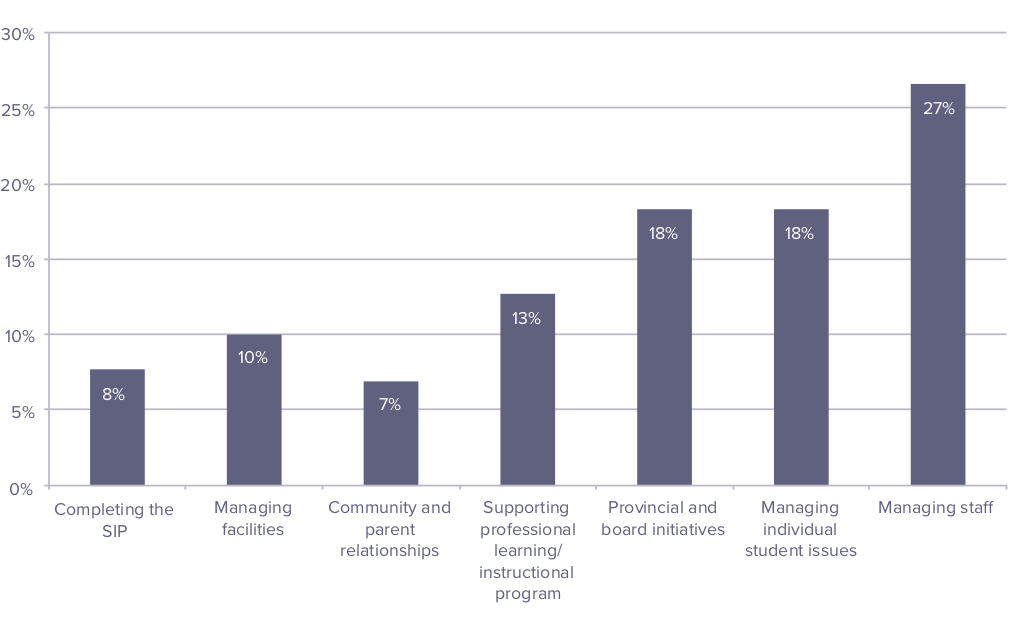

In order to understand more about Ontario principals’ work, we asked them to rank the following seven tasks in terms of how much time they take (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2):

- Managing staff (human resources functions and collective agreement implementation)

- Managing individual student issues

- Provincial and board/system initiatives (communications, documentation, meetings related to policy and programs, etc.)

- Supporting professional learning and improving the instructional program

- Community and parent relationships

- Managing facilities

- Completing the School Improvement Plan (SIP)

I love my job. Working with parents is huge—can be rewarding but also the most challenging. I feel if the teachers are happy and receiving the appropriate amount of PD and School Improvement Planning communication, I seem to have to deal with less individual student issues. Having a strong resource team is key.

Elementary school, Ottawa Catholic DSB

Figure 1.1 Elementary principals’ most time-consuming tasks

School management vs. professional learning

Principals are required to oversee both the quality of education in the school (including professional learning for staff, improving the instructional program, etc.) and the management of the school itself (administrative tasks). According to one elementary principal, “Over the past few years, the school administration role has changed from one of instructional leader, a supporter of students and staff, to a managerial role.”1

Only a small proportion of principals (9% of elementary and 13% of secondary schools) report that their most time-consuming task is supporting professional learning and improving the instructional program. This is consistent with recent research showing an overload of administrative work for principals in schools across Canada (Alberta Teachers’ Association, 2014; Leithwood & Azah, 2014).

We spend so much time managing significant mental health issues with students, and managing staff and facility issues that I never feel we can move ahead with the student learning agenda.

Secondary school, Limestone DSB

When I am able to focus on professional learning with teaching staff, we see a direct influence on student engagement and achievement.

Elementary school, York Region DSB

Supporting individual students

In this year’s survey, one of the most urgent issues raised by principals is students’ increasing mental health needs. It is unclear whether this is a result of increased awareness of mental illness (e.g. Bell Canada, 2015), increased incidence (e.g. Cribb, Ovid, Lao, & Bigham, 2017), reduced stigma (e.g. Chai & Nicolas, 2017), other factors, or a combination of these. Many principals also comment that student behavioural issues require a great deal of their time.

Schools are addressing these issues on a daily basis, adding complexity to the role of educators in our communities. Principals report that existing mental health resources such as social workers, psychologists, and guidance counsellors, are insufficient to meet students’ needs, and that mental health issues are taking up an increasing amount of their time and resources.

In 2018, the province announced funding for mental health workers in secondary schools. These workers will be introduced into schools gradually over the next two years (Office of the Premier, 2018).

Figure 1.2 Secondary principals’ most time-consuming tasks

There are way too many managerial and day-to-day running-of-the-school tasks that professional learning and instructional programming is left to the last, and done superficially, and not as good as it could be.

Secondary school, Simcoe County DSB

[It is] very challenging to balance the principal role. The needs of our students are becoming increasingly complex. Mental health issues have been more prominent in our day-to-day dealings, with minimal support and limited expertise in the building.

Elementary school, Durham DSB

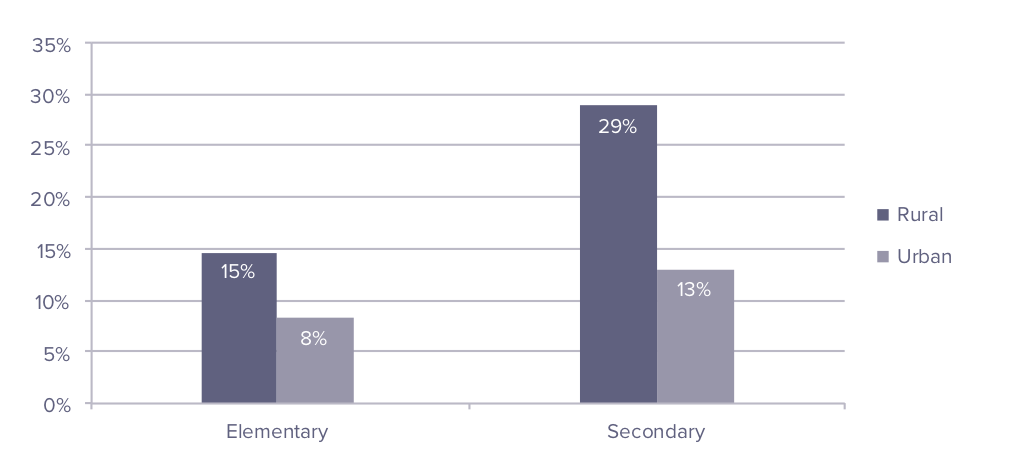

The urban-rural divide

There is a marked difference between urban and rural elementary schools in the proportion of principals who say they spend the most time managing individual student issues (see Figure 1.3). This may be partly attributable to the presence of vice-principals (VPs). Elementary schools in urban areas are more likely to have a VP, and over twice as likely to have a full-time VP, than those in rural areas. Similar trends are seen in secondary schools.

The demands of paperwork and HR

A common concern raised by principals is that demands from the board/ Ministry, and the accompanying paperwork and emails, take up a large portion of their time. Some principals feel that, in order to keep up, they either have to work extremely long hours or lose opportunities to be instructional leaders.

Hiring staff—including teaching, administrative, and support staff—is also a significant challenge for principals. Several principals report being understaffed and short of resources to complete the various administration tasks that keep schools running.

Managing daily student behaviour issues…and making related necessary parent contacts, consumes so much of the principal’s working day that curriculum leadership and leading the improvement of instructional programming and other board/Ministry initiatives is severely compromised.

Elementary school, Avon Maitland DSB

Being alone in management, meeting with parents and students is a task that requires a lot of time and energy. The integration of students with special education needs into regular classes requires management of human resources on a daily basis.2

Elementary school, Conseil des écoles catholique du Centre-Est

Figure 1.3 Percentage of principals reporting that they spend the most time managing student issues

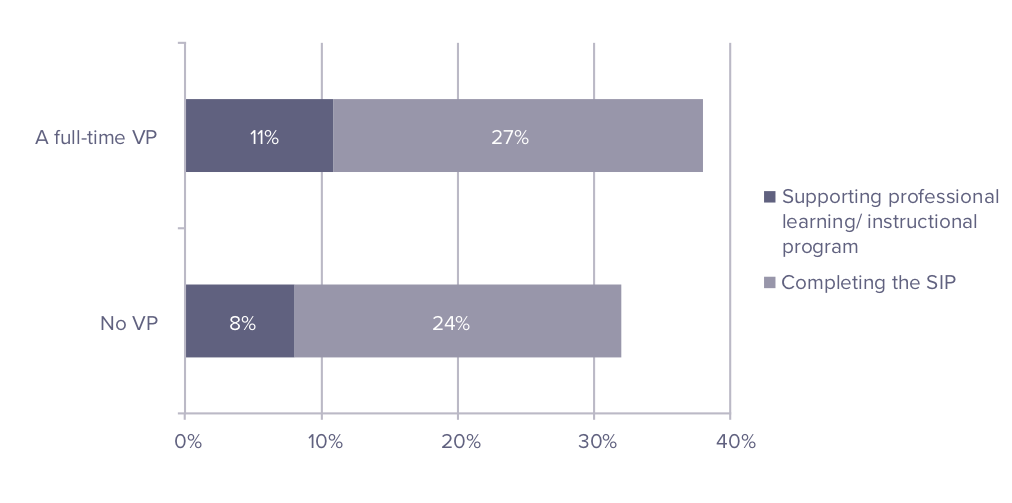

Vice-principals provide support

Vice-principals are a central part of the school’s leadership team. Under the Education Act, the role is vaguely defined as duties and responsibilities assigned by the principal to the vice-principal (Education Act, RRO, 1990). The vice-principal works with the school principal in all aspects of leading and managing the school, and is often responsible for managing student discipline issues and special education.

Having a vice-principal has an impact on how principals spend their time. Elementary schools with at least one full-time VP are more likely to report that the principal spends the most time improving the instructional program and completing the School Improvement Plan (SIP) (see Figure 1.4).

Principals from elementary schools with at least one full-time VP are also less likely to spend the most time on management of staff, individual student issues, or facilities (see Figure 1.5).

Hiring is a big issue in our board – and when you aren’t doing the hiring yourself, you are asked to support others with large hiring needs, and are even asked to hire on weekends. Applies to teaching and support staff like secretarial staff.

Secondary school, Peel DSB

Too much time dedicated to paperwork that could be better dedicated to pedagogy.3

Elementary school, Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir

Figure 1.4 Impact of VPs on principals’ time leading the instructional program

Figure 1.5 Impact of VPs on principals’ time managing the school

We have a significant staff shortage for casual and sup- port staff positions. I spend a lot of time finding supply coverage, assigning on-calls, and in some cases, being an admin assistant or EA when we are that short.

Secondary school, Keewatin-Patricia DSB

Principals influence student learning

There is no question that within the school, teachers have the greatest influence on student success. However, out of all other school-related factors, school principals have the highest impact on students’ education (Leithwood, Seashore Louis, Anderson, & Wahlstrom, 2004).

Recommendations

This year’s survey results make it clear that it is a challenge for today’s principals to find the time to fulfill their role as curriculum leaders, while also managing all of the administrative tasks involving the school building and staff. More than one fifth of elementary school principals report that managing facilities is the most time-consuming part of their job, while only nine percent report that supporting professional learning and the school’s instructional program takes the most time.

People for Education recommends that the province:

- Work with the Ontario Principals’ Council, the Catholic Principals’ Council of Ontario, and the Association des directions et directions adjointes des écoles francophones, to identify where more supports are required and how demands on administration time can be alleviated, so that principals can focus more of their time on student learning and staff development.

1 Comment from an elementary school in Avon Maitland DSB

2 Translated from French. Original comment: “Étant seule à la direction, l’accueil des parents et des élèves est une tâche qui demande beaucoup de temps et d’énergie. L’intégration des élèves en difficulté dans les classes régulières demande une gestion des resssources humaines sur une base quotidienne.”

3 Translated from French. Original comment: “Beaucoup trop de temps dédié à la paperasse qui pourrait être mieux dédié à la pédagogie.”

In 2018:

-

20% of elementary and 26% of secondary schools report that the most time- consuming part of their guidance counsellors’ job is providing one-on-one counselling to students for mental health needs.

-

Among secondary schools with guidance counsellors, the average ratio of students to guidance counsellors is 396:1. In 10% of schools, this average jumps to 826:1.

-

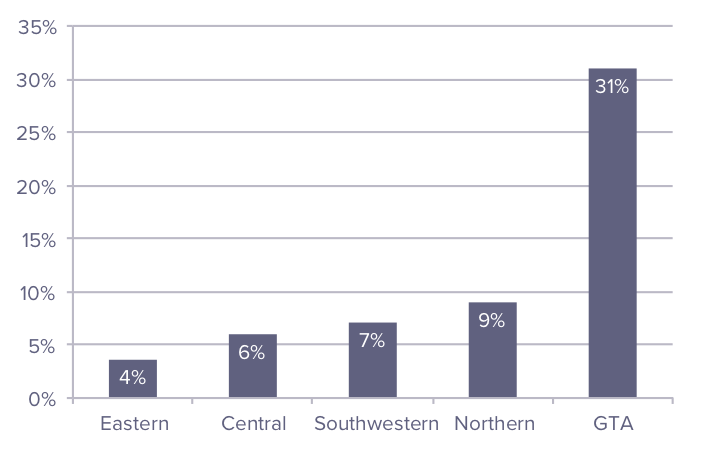

31% of elementary schools in the Greater Toronto Area have guidance counsellors, more than triple any other region in the province.

Guidance counsellors are a staple of secondary school staff in Ontario, and virtually every school reports having at least part-time guidance staff. But guidance counsellors’ roles vary between schools, depending on student needs, staffing, and board/school priorities.

According to the Ontario School Counsellors’ Association (n.d.), the mission of a guidance counsellor is to support students’ well-being and growth in three areas:

- Personal development

- Interpersonal development

- Career development

In many of Ontario’s education policies, the role of guidance staff is cited as helping students with transitions and academic programming. For example, the 2013 career and life planning policy document, Creating Pathways to Success, states that “guidance staff play a strategic role

in the development and implementation of the [Pathways] program…” (Ontario, 2013a, p. 4). Guidance counsellors also play a key role in Specialist High Skills Majors (Ontario, 2016c), cooperative education, and other forms of experiential learning (Ontario, 2000, p. 44).

However, guidance counsellors have responsibilities beyond helping students determine their career paths. Guidance personnel are referenced as core members of the in-school support team in the 2010 progressive discipline document, Caring and Safe Schools (Ontario, 2010, p. 58). They are also expected to respond to student mental health issues, according to the 2013 mental health and well-being document, Supporting Minds (Ontario, 2013b pp. 93-95).

Students’ mental health needs: A challenge for guidance staff

In 2018, many secondary school principals report that the mental health needs of their students are a huge challenge for guidance staff.

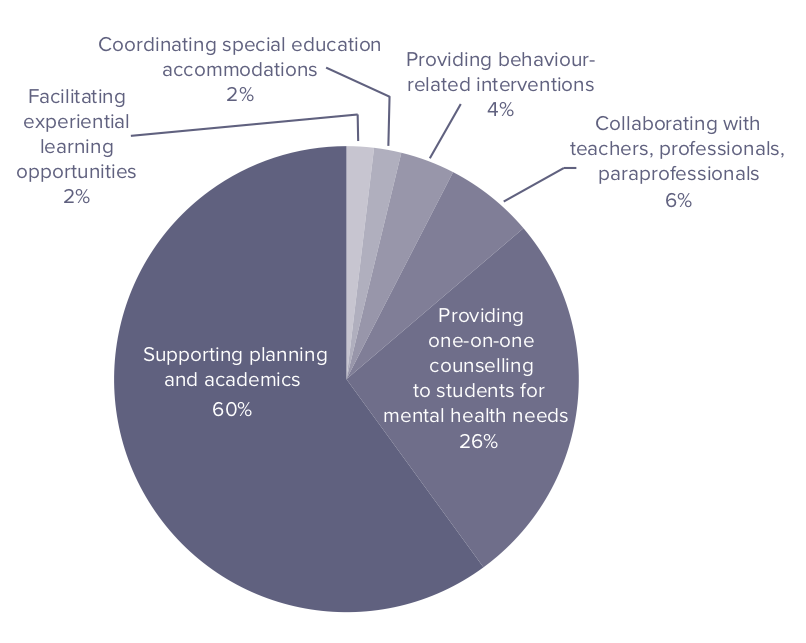

This year, schools were asked to rank their guidance counsellors’ roles, from most to least time-consuming:

- Providing one-on-one counselling to students for mental health needs

- Supporting planning and academics (e.g. All About Me, Individual Pathway Plans, course selection with students, school applications)

- Collaborating with teachers, professionals, paraprofessionals (e.g. social workers, psychologists, child and youth workers)

- Providing behaviour-related interventions (e.g. classroom disruptions, bullying)

- Facilitating experiential learning opportunities (e.g. co-ops, internships, Dual Credits) (for secondary schools only)

- Coordinating special education accommodations (for secondary schools only)

Predictably, the majority of schools report that their guidance counsellors spend more time supporting students with academic and transition planning than any other task. However, supporting students’ mental health needs was ranked second highest. Twenty-six percent of secondary and 20% of elementary schools indicate that the most time- consuming part of the guidance counsellor’s role is providing one-on- one counselling to students for mental health needs (See Figure 2.1).

This is consistent with data from 2016, when 25% of secondary schools indicated that the most time-consuming job for guidance staff was supporting student mental health issues (People for Education, 2016, p. 12).

In 2017, People for Education reported that 40% of secondary schools had regularly scheduled access to a psychologist4 (People for Education, 2017, p. 6). In the same year, half of secondary school principals reported that they did not have sufficient access to psychologists to adequately support students. When resources such as psychologists and social workers are limited, the role of guidance counsellors may be stretched to fill gaps.

Mental health needs are increasing at an alarming rate and we do not have access to the professional services to truly help these students.

Secondary school, Kawartha Pine Ridge DSB

Figure 2.1 The most time-consuming task for guidance counsellors in secondary schools

Per pupil amounts in funding formula limit support for guidance staff

School boards receive funding for secondary school guidance counsellors at a rate of one full-time teacher for every 385 students (Ontario 2017a, p. 26-29). This ratio is reflected in this year’s results: among secondary schools with guidance staff, the average ratio of students to guidance teachers is 396:1. However, in 10% of secondary schools this average increases to 826:1.

In 2018, only 14% of elementary schools have guidance counsellors, and the majority are part-time. In elementary schools that include grades 7 and 8—where students are preparing to transition to secondary school—only 20% have guidance counsellors, and the majority are part- time. Among elementary schools with a guidance counsellor, they are scheduled for an average of 1.5 days per week. Principals comment that the current staffing levels are not sufficient.

The Ontario Student Trustees’ Association (OSTA-AECO) 2018 “Student Platform” included a recommendation that the student to guidance counsellor ratio for elementary schools should match the ratio for secondary schools, and that the ratio of students to guidance teachers should be narrowed at both levels (OSTA-AECO, 2018, p. 5). People for Education has also recommended funding changes, in particular to support guidance counsellors for students in grades 7 and 8 (People for Education, 2018c).

These efforts have had an impact. In 2018/19, the province will begin to implement changes to funding for guidance counsellors for students in grades 7 and 8 so that they will be funded at the same rate as guidance counsellors in secondary schools (Ontario, 2018a, p. 23).

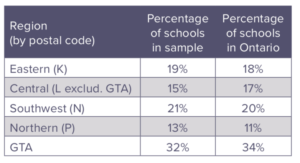

Regional discrepancies

Because funding for guidance counsellors is provided on a per pupil basis, access to guidance counsellors in elementary schools varies markedly across the province. In the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), 31% of elementary schools have guidance staff, compared to an average of 6% across the rest of the province (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Percentage of elementary schools with guidance counsellors, by region

Recommendations

Guidance counsellors can play a key role in students’ lives. They support students in planning transitions, seeking help for mental health issues, learning to act as advocates for themselves in connection with special education needs, and developing educational pathways that will lead to long-term success. Many principals report that guidance counsellors are “pulled in too many directions,” or are challenged by the number of students they are expected to support.

People for Education recommends that the province:

- Evaluate current education policies that may include guidance counsellors, in order to rationalize Ontario’s guidance programs and create greater alignment across these policies.

- Continue to implement changes to the funding formula so that schools with grades 7 and 8 have guidance counsellors at a ratio of 384 to 1.

- Clarify the role of both elementary and secondary school guidance counsellors in a way that recognizes both the breadth of their responsibilities and their relative scarcity in Ontario schools.

- Explore cost-effective ways for guidance staff support to be expanded in small towns and rural areas, to ensure students in these areas have equitable access to guidance counsellors.

4 In this document the term “psychologist” includes registered psychologists and registered psychological associates, as well as supervised non-registered psychology service providers in schools.

In 2018:

-

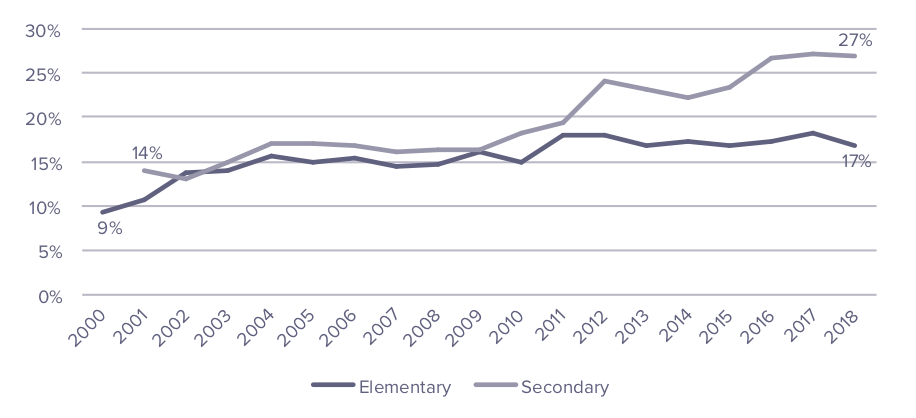

An average of 17% of students per elementary school and 27% per secondary school receives special education support.

-

66% of elementary schools and 53% of secondary schools report a restriction on the number of students that can be assessed for special education each year – a trend that has been increasing among elementary school over the years.

-

92% of urban elementary schools have a full-time special education teacher, compared to 72% of rural elementary schools.

-

58% of elementary principals and 48% of secondary principals report that they have had to recommend a student with special education needs not attend school for the full day – the majority for safety reasons.

-

93% of elementary schools and 97% of secondary schools report that students waiting for an assessment are receiving some special education support.

Almost all schools in Ontario have some students receiving special education support. In elementary schools, an average of 17% of students per school are getting special education support. In secondary schools the average is 27% (see Figure 3.1). The kind of support students receive depends on both their individual needs and the resources available.

Students getting support without formal identification

Special education covers a wide range of supports and interventions— from a little extra help in a regular class to the provision of specialized medical equipment and one, or even two, dedicated staff. Students with higher needs usually go through a formal identification process; others may have no specific special education “label”, but are supported through Individual Education Plans (IEPs).

Approximately half of students receiving special education support have an IEP without a formal identification (Ontario, 2017d). These students may have a learning disability, or may simply need a little extra help. The support they get can include things like extra time for writing tests, occasional help from an educational assistant, adjustments to the way they are marked, or other strategies or accommodations agreed to by the teacher, parents, and student.

Students who have been formally identified through an Identification Placement and Review Committee (IPRC) have special education needs that fit into at least one of five provincially-recognized categories: behavioural, communication, intellectual, physical, or multiple exceptionalities. These students have a legal right to special education support (Education Act, RSO, 1990), which can include specialized equipment, withdrawal for all or part of the day to a class with a special education teacher, support from an educational assistant, modifications to the curriculum, and/or specialized classes (Ontario, 2017c).

Figure 3.1 Average proportion of students receiving special education support per school

Staff support

Students with special education needs receive support from staff in a range of ways, including:

- Occasional support from an educational assistant in a regular classroom

- Support from the classroom teacher, who is in turn supported by a specialist special education teacher who works with all of the teachers in the school

- Support from a specialist special education teacher, either in their regular classroom or withdrawn for part of the day

- Placement in a separate class with a specialist special education teacher, with or without some time spent in a regular class

Nearly all schools have at least a part-time special education teacher. However, only 72% of rural elementary schools report a full-time special education teacher, compared to 92% of urban schools. This has been consistent over the past several years.

The average ratio of students receiving special education support to special education teachers is 36:1 in elementary school and 74:1 in secondary school.

Eighty-eight percent of elementary and 94% of secondary schools have educational assistants (EAs) who provide vital support, both to classroom teachers and to students. Educational assistants help students with ongoing lessons, assist with personal hygiene, and support students in managing their behavior. The average ratio of students receiving special education support to educational assistants is 19:1 in elementary schools and 61:1 in secondary schools.

Special Education needs continue to rise, as support continues to be cut. Many students with Autism Spectrum Disorder who require full time support do not receive it; thus making it a safety concern for all involved. More money needs to be put into special education in order to provide these students with the care and education they should receive; just like all other students.

Elementary school, York Catholic DSB

We don’t have enough special education support to provide services to students who are not identified but who still have significant challenges.

Elementary school, Rainbow DSB

Parents are being asked to keep some students home

While most schools have educational assistants, principals continue to report that they have insufficient support for their students with special education needs. One consequence may be that there are times when principals ask parents to keep students home. Since 2014, there has been an increase in the percentage of schools that report having asked that a student be kept home for all or part of the school day. It is unclear what is causing this change—an increase in the frequency/severity of behaviour problems, a decrease in available resources, or some combination of these.

In 2018:

- 58% of elementary and 48% of secondary school principals report they have had to recommend a student with special education needs not attend school for the full day. This is a substantial increase from 48% and 40% respectively, in 2014.

- 73% of elementary principals who answered “yes” to this question, said it was for safety reasons, while 18% said it was because supports were not available.

Waitlists and restrictions

In order to be formally identified with a recognized special education exceptionality under Ministry of Education guidelines (Ontario, 2017d), students must be assessed by a specialist such as a psychologist,5 speech-language pathologist, or physician. In last year’s survey, 38% of elementary and 40% of secondary schools reported having regularly scheduled access to psychologists, while 13% of elementary and 16% of secondary schools reported having no access at all (People for Education, 2017).

The lack of access to specialists can result in students having to wait for assessments. Wait times vary, based on the severity of student needs and the school board’s policy for waiting lists. This year, 93% of elementary and 79% of secondary schools report that they have students on waiting lists. It is important to note, however, that while students are waiting for assessment, they are not necessarily going without support. The vast majority of schools report that students waiting for special education assessments have Individual Education Plans (89% of elementary and 97% of secondary) and are receiving special education support (93% of elementary and 97% of secondary). Many school boards impose restrictions on the number of students who can be assessed per year (see Figure 3.2), often because of limited access to specialists.

Almost all of our EAs support students with safety, behavioural, and/or communication challenges. If I have asked a parent to keep a student home it is almost always related to safety (the student runs, hits self/peers/ adults, or vandalizes the space he/she is in). Even with 14 EA FTEs I have new needs that enter my school regularly which means I am stretched thin.

Elementary school, Halton DSB

The Psychologist and Speech Language Pathologist only come once a week, and the number of students in need of assessment is overwhelming. We are in a poor socio- economic area and parents do not have the financial resources to do private assessments. We have a number of students that are on the Autism spectrum and/or have behavioural issues, and not having full day support for these children makes it a safety issue (to themselves and others). Also, having to cluster support does not always function very well. We are finding that students are not making the gains they could because of the distraction of 1 EA having to go between 3 to 4 students with high needs.

Elementary school, Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB

Figure 3.2 Percentage of schools reporting a restriction on the number of students to be assessed

In 2018:

- 66% of elementary schools and 53% of secondary schools report there is a restriction on the number of students who can be assessed.

- 73% of rural elementary schools report restrictions, compared to 61% of urban schools.

In March 2018, the Ontario Ministry of Education announced $72 million in funding for the 2018/19 school year to reduce waiting lists for special education assessments and to “increase services through multi- disciplinary teams and other staffing resources” (Davis, 2018).

The impact of parental education and income

This year, we used information from Statistics Canada and Ontario’s Ministry of Education to examine the relationship between students’ family background and a range of resources and programs in schools. We compared the top and bottom 25% of our elementary school sample in two areas: the proportion of families under the Low-Income Measure, and the proportion of students with at least one parent who has graduated from university. For the sake of comparison, we refer to these as high and low poverty schools, and high and low parental education schools.

Two-tier system for parents who have money to pay for assessments [outside of the school system]. 6

Elementary school, Conseil des écoles publiques de l’Est de l’Ontario

We are given 2 assessments per year and they usually come late in the school year. Given our geographic location, there are not a lot resources available to the students (and their parents) on the autism spectrum or who have difficulty with behaviour and/ or mental wellness.

Elementary school, Algonquin and Lakeshore Catholic DSB

Many researchers suggest that students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to be identified with certain kinds of special needs. These families have less access to services, fewer monetary resources, lower educational backgrounds, and may have less confidence to advocate for their children than more affluent families (Ong-Dean, 2009). As a result, there may be an over-representation of lower income students in special education classes (Brown & Parekh, 2013).

In 2018, students in elementary schools with lower levels of parental education, and in schools with higher poverty, were more likely to be receiving special education support:

- On average, 12% of students in elementary schools with high parental education receive special education support, compared to 23% of students in elementary schools with low parental education. This includes both students with a formal diagnosis, and those with an IEP.

- On average, 13% of students in low poverty elementary schools receive special education support, compared to an average of 16% in high poverty elementary schools.

Recommendations

Over the years, the province has increased overall funding for special education, and introduced a range of models and formulas to allocate the funding to school boards. In the last four years, some of those changes have resulted in funding increases for some boards and decreases for others. However, principals continue to point to both delivery of special education services and support for students with mental health issues as significant stresses in their schools.

People for Education recommends that the province:

-

Provide adequate support to educators in kindergarten and the early grades to ensure they have the time and capacity to identify students who may need special education support.

-

Ensure that students who require special education support are receiving it as early as possible. By addressing special education needs early, some students may not require support in later grades.

-

Consider re-distributing some of the funding currently targeted at reducing waitlists to provide more on-the- ground support, including increased numbers of educational assistants.

5 In this document, the term “psychologist” includes registered psychologists and registered psychological associates, as well as supervised non-registered psychology service providers in schools.

6 Translated from French. Original comment: “Système à 2 vitesses pour les parents qui ont de l’argent pour débourser l’évaluation.”

In 2018:

-

94% of elementary schools and 100% of secondary schools report collaborating with mental health care services.

-

53% of elementary schools have a specialist health and physical education (H&PE) teacher, full- or part-time, compared to 42% in 2017.

-

39% of elementary schools in rural areas have H&PE teachers, compared to 62% of those in urban areas.

-

Among elementary schools with an H&PE teacher, 80% have advanced training.

-

62% of urban elementary schools have H&PE teachers, compared to 39% of rural elementary schools.

Students bring not just their minds, but their complete selves to school. Resources that support student health and physical activity are pivotal in ensuring that students graduate from school prepared to make healthy choices throughout their lives (Ferguson & Power, 2014).

Specialists on the rise

In this year’s survey, 53% of elementary schools report having a health and physical education (H&PE) teacher. This reflects a general upward trend since the beginning of the Annual Ontario School Survey in 1998 (see Figure 4.1). The percentage of schools reporting that their H&PE teacher is full-time has also increased, from 18% in 1998 to 39% this year.

Among those schools with H&PE teachers, 80% report that their teachers have some sort of advanced training for H&PE (e.g. an Additional Qualification course, a degree in a relevant field, or professional development around H&PE teaching).

Some studies have shown that being taught by specialist H&PE teachers can lead to better health and academic outcomes for elementary students (e.g. Telford, et al., 2012). In Ontario, children generally receive the same amount of instruction time in physical education, regardless of whether a specialist or generalist is teaching (Faulkner, et al., 2008). However, in schools where specialist teachers are responsible for H&PE, students are more likely to be engaged in intramural sports. Faulkner et al. suggest that this is because specialists may have more resources and a greater interest in developing and promoting these opportunities for students. On the other hand, Ophea—a non-profit organization

that supports health and physical education in Ontario—suggests that both qualified elementary teachers and H&PE specialists are capable of delivering quality physical activity initiatives and programs (Ophea, 2016).

This year, we matched our survey results to data from grade 3 and 6 student questionnaires completed as part of the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) assessments. The results indicate that students attending schools with at least one full-time H&PE teacher are slightly more likely to participate in sports or other physical activities outside the school day, every day or almost every day, when compared to schools with no H&PE teacher.

In a recent survey of parents, Ophea found that 79% of Ontario parents agree that teaching H&PE in schools helps prepare their children to address health issues (Ophea, 2018).

It is amazing to have a dedicated H&PE teacher. He also does yoga, meditation and self-regulation strategies with them.

Elementary school, Simcoe Muskoka Catholic DSB

Figure 4.1 Percentage of elementary schools with a H&PE teacher full- or part-time

Increased funding for specialists

As with most specialist teachers, there is no specific funding designated for H&PE teachers. Instead, school boards are allocated funds on a per-pupil basis to cover the costs of preparation time for classroom teachers. In elementary schools, while classroom teachers are using their preparation time (for things like marking, preparing, collaborating with other teachers, and communicating with parents), their classes are taught by specialist teachers in subjects like H&PE. The larger the school, the more preparation time is generated; thus larger schools have more funding to hire more specialist teachers. Elementary schools with at least one full-time H&PE teacher have, on average, 45% more students than those without a full-time H&PE teacher.

In 2017/18, the Ministry of Education increased the amount of funding for specialist teacher/preparation time (Ontario, 2016b; 2017b). This change in funding may be partly responsible for the eleven percentage-point increase seen in H&PE teachers this year.

Excellent teacher and involved in many areas; qualified up to [H&PE Additional Qualification] part 3. He knows all the students and their strengths and needs. He is involved in many extracurricular and sports activities with several members of our staff.7

Elementary school, Conseil Scolaire Catholique Providence

More specialists in urban schools

In this year’s survey, elementary schools in urban areas are more likely to have H&PE teachers than those in rural areas (see Figure 4.3). Overall, 39% of elementary schools in rural areas have H&PE teachers, compared to 62% of those in urban areas. In part, this gap can be attributed to school size. However, a slight difference persists even when school size is taken into account.

In addition to having more teachers, urban regions are more likely to have H&PE specialists with advanced training. Among schools in rural areas with H&PE teachers, 77% have advanced training, compared to 82% in urban areas.

[Challenges with H&PE:] just timetabling. Students should have Physical Education every day in my opinion.

Elementary school, Toronto DSB

We share a gym with another larger school. None of the classes have access to the gym every day. It’s either twice or 3 times a week in a 5-day cycle. It’s difficult (next to impossible) to get additional gym time for sports if we want to practice at lunch, as an example.

Elementary school, Huron-Superior Catholic DSB

Daily activity is a challenge

In 2014, the Ontario government announced it would work to implement 60 minutes of physical activity, connected to the school day, for all students (Office of the Premier, 2014), and in 2018, a survey of Ontario parents found that 99% believe it is important for their children to be physically active for at least 60 minutes each day (Ophea, 2018).

However, data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey from 2009 to 2015 indicate that only 7% of Canadian children and youth accumulated at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity on at least 6 out of 7 days (Colley et al., 2017). The study, which used accelerometers to measure movement, also found that boys accumulated more physical activity than girls, and children (6- to 11- year olds) were more physically active than youth (12- to 17-year olds). The levels of physical activity have remained relatively consistent over time, and have not changed substantially with the introduction of new initiatives.

Figure 4.2 Percentage of elementary schools with H&PE teachers

In 2017, the Auditor General reported that there was progress in the implementation of the 20-minute Daily Physical Activity requirement in elementary schools, but “little or no progress” towards increasing physical activity to 60 minutes (Auditor General, 2017).

In this year’s survey, many principals commented that having adequate space and equipment for students is a significant challenge in providing physical education.

[Challenges with H&PE:] space. One small gym in the basement, one auditorium, and not enough large space in the school.

Elementary school, Toronto DSB

Our biggest challenges are supporting students and their families regarding mental health issues. Education has changed tremendously and we spend much of our time providing support for issues that are outside of the classroom/school.

Elementary school, Upper Canada DSB

Supporting students’ mental health

Health and physical education is not only about sports and exercise. It also includes learning about taking care of mental health, understanding and managing risks, and knowing how to recognize signs of mental illness and when to get help with mental health issues. According to a recent poll conducted by Ophea and Environics, 90% of Ontario parents “agree” or “strongly agree” that mental health should be taught as a component of the H&PE curriculum (Ophea, 2018).

Supporting students’ mental health is a central goal for the Ministry of Education. In 2009, the province amended Ontario’s Education Act to make the promotion of well-being a responsibility of every school board (Education Act, RSO, 1990), and mental health and wellbeing are core components of the province’s Wellbeing Strategy, introduced in 2014 (Ontario, 2016d).

However, it is clear from the concerns raised in this year’s survey that supporting and promoting mental health, and ensuring there are adequate resources and supports for students struggling with mental illness, continue to present serious challenges.

Figure 4.3 Percentage of schools that report connecting with mental health care services

People for Education—in collaboration with academics and educators— has identified specific health and social-emotional competencies that contribute to a whole-school approach to supporting mental health. (Ferguson & Power, 2014; Shanker, 2014) To be effective, these competencies can and should be integrated within curriculum and policy from kindergarten through grade 12, foregrounded as a central area of focus for educators, and recognized as a valued outcome of learning, rather than an add-on or by-product of academic achievement.

Most schools in Ontario are reaching beyond the education system to connect students and their families with mental health services and support. In 2018, 94% of elementary and 100% of secondary schools report connecting or working with mental health care services (see Figure 4.3).

While the vast majority of schools report collaborating with mental health organizations, there may still be issues with access to support. In 2017, 47% of elementary schools reported that they did not have access to child and youth workers, 15% did not have access to social workers, and 13% did not have access to psychologists. This year, many principals commented on the challenge of supporting students who are struggling with mental illness.

Mental Health and behaviour challenges are on the rise and require much more time and attention than has been needed in the past. This often takes away from the time needed on academic school improvement. The good news is that we have been given the opportunity to focus on well-being as part of our School Improvement Planning, with resources to support this. Unfortunately, the need still far out-weighs the available resources in schools each day.

Elementary school, Waterloo Region DSB

Most schools in Ontario are reaching beyond the education system to connect students and their families with mental health services and support. In 2018, 94% of elementary and 100% of secondary schools report connecting or working with mental health care services (see Figure 4.3).

While the vast majority of schools report collaborating with mental health organizations, there may still be issues with access to support. In 2017, 47% of elementary schools reported that they did not have access to child and youth workers, 15% did not have access to social workers, and 13% did not have access to psychologists. This year, many principals commented on the challenge of supporting students who are struggling with mental illness.

Recommendations

Students’ mental and physical health has an impact on both their education and their long-term success. It is vital to recognize – with policy, curriculum, resources and professional supports – that supporting students’ health is one of the “basics.” It is also vital to foster mental health promotion and illness prevention strategies, rather than focusing solely on reactions and supports for mental illness. Doing this will ensure that students:

- Develop vital social-emotional and health competencies

- Are able to make healthy choices

- Have the capacity to recognize when they need help

- Develop life-long health promoting habits and behaviours

People for Education recommends that the province:

-

Work with a range of stakeholders to create learning spaces and environments that maximize student wellbeing and social- emotional learning.

-

Integrate social-emotional and health competencies across the curriculum, and provide adequate resources and capacity- building for staff to support both themselves and their students.

7 Translated from French. Original comment: “Excellent enseignant et impliqué dans bien des domaines. Il est qualifié jusqu’à la partie trois. Il connaît tous les élèves et leurs forces et besoins. Il s’implique dans plusieurs activités parascolaires et sportives avec plusieurs membres de notre personnel.”

In 2018:

-

74% of elementary and 84% of secondary schools offer at least one Indigenous learning opportunity, compared to 34% and 61% respectively in 2014.

-

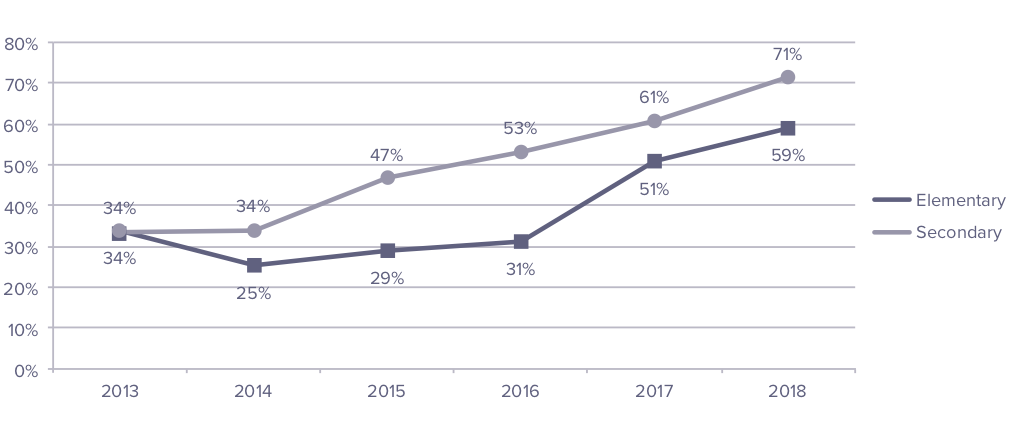

59% of elementary and 71% of secondary schools report providing professional development for teachers around Indigenous cultural issues.

-

21% of elementary schools and 46% of secondary schools report having a self- identified Indigenous person on staff.

-

87% of elementary schools with an Indigenous staff member have at least one Indigenous education opportunity, compared to 67% of those without an indigenous staff member.

It has been ten years since Ontario released its First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework. The strategy called for improving achievement for Indigenous students, closing the gap in achievement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, and ensuring all students gain an understanding of Indigenous cultures, experiences, and perspectives.

Ten years along, People for Education’s data show considerable gains on the last of those objectives. But the fundamental challenge of significantly raising achievement for Indigenous students remains (Ontario, 2018b).

We have one third of our students/families who self-identify and are very supportive of providing input and guidance around our work. We also have very strong staff leadership in this area of wellness and student belonging.

Elementary school, Algonquin and Lakeshore DSB

Ensuring all young people learn about Indigenous cultures and experiences

There has been a significant increase in the percentage of schools who report providing Indigenous education opportunities. This increase reflects a broader societal awareness, deliberate policy efforts, and a substantial increase in the re-named Indigenous Education Grant (up $54 million to $66.3 million in the last ten years). It also reflects some of the goals laid out in The Journey Together (Government of Ontario, 2016), the provincial government’s response to the Calls for Action from the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC; TRC, 2015, pp. 319- 337).

This year, 74% of elementary and 84% of secondary schools report offering at least one Indigenous learning opportunity (professional development, cultural supports, guest speakers, community consultation, ceremonies, Indigenous Studies courses, or Indigenous language programs). This is a substantial increase from 2014, when only 34% of elementary and 61% of secondary schools reported offering any Indigenous learning opportunities (see Figure 5.1).

In their survey responses, principals describe a wide range of initiatives in their schools: school-wide recognition of Indigenous culture, medicine gardens or canoes built by students and elders, activities for Treaty Recognition Week or Orange Shirt Day (commemorating the history of residential schools), assemblies, field trips, land acknowledgements, and Indigenous national anthems.

Some schools report strong integration into the mainstream curriculum, including things like an entire grade 9 visual arts course taught through Indigenous themes, curricular support for all staff from a trained teacher- librarian, and a commitment to ensure Indigenous art and literature is available in all classrooms.

Figure 5.1 Percentage of schools offering Indigenous education opportunities

Supporting teachers’ learning

In its Calls to Action, the TRC specifically called for supports to help teachers learn how to teach Indigenous content. One of the most important recent changes in the school system is a revision of the curriculum in all subjects and all grades. This revision, developed collaboratively with Indigenous partners, includes “mandatory learning about the impact of colonialism and the rights and responsibilities of all people in Canada with respect to understanding the shared history and building the collective future in the spirit of reconciliation” (Ontario, 2018b, p. 17).

In this year’s survey, 59% of elementary and 71% of secondary schools report professional development (PD) for teachers around Indigenous cultural issues, up from 34% in both elementary and secondary in 2013 (see Figure 5.2). Since the requirement for Indigenous content in teacher education is relatively recent (Ontario College of Teachers, 2013), ongoing PD is the most effective way to ensure all teachers are developing the required knowledge and confidence to teach in this area (e.g. Craven, Yeung, & Han, 2014; Nardozi & Mashford-Pringle, 2014).

Professional development matters since, in the words of one principal, “there are few resources for staff who themselves are still learning about the Indigenous struggle.”8 PD may also help teachers understand why Indigenous education is important for all students, as a significant number of principals still comment on limited interest or even resistance to prioritizing this learning in their schools.

We know we have some students who identified as Indigenous in our last student climate survey, however they have yet to identify themselves to us.

Elementary school, York Region DSB

I would like the board to mandate Indigenous education training and offer workshops much like they do for Numeracy and Literacy and for We Rise Together supporting black male youth at high school. The board has not mandated Indigenous training, I think they should.

Elementary school, Peel DSB

Figure 5.2 Percentage of schools with professional development around Indigenous cultural issues

Learning from Indigenous people in Ontario schools

One of the key performance measures identified in the First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Framework is a “significant increase in the number of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit teaching and non-teaching staff in school boards across Ontario” (Ontario, 2007b, p. 11). However, the province does not require boards to collect the data needed to assess progress on this measure (Ontario, 2018b, p. 56).

This year, for the first time, People for Education asked schools if they have staff who self-identify as Indigenous:

- 21% of elementary schools report having self-identified Indigenous staff.

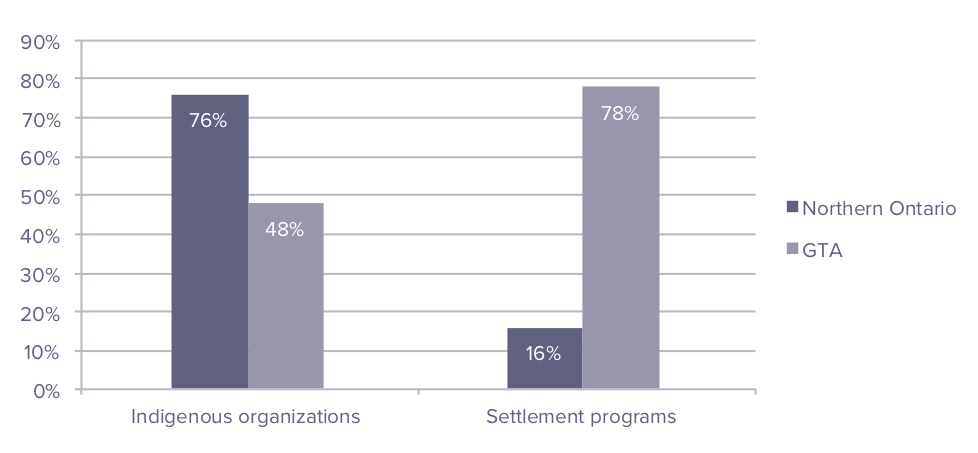

- 40% of elementary schools in Northern Ontario have Indigenous staff, compared to only 14% of schools in the Greater Toronto Area.

- 46% of secondary schools—which generally have larger staffs, and thus a greater likelihood of diversity—report a self-identified Indigenous person on-staff.

It is evident from the survey results that having Indigenous staff has an impact on the number of Indigenous education opportunities offered in schools (see Figure 5.3). However, it is important to recognize that being the only, or one of a few, Indigenous teachers in the school community can put added pressures on these educators, and they may experience additional barriers of racism and oppression in the school space (Kholi & Pizzaro, 2016).

Figure 5.3 Impact of self-identified Indigenous staff on Indigenous education opportunities

Effective partnerships with local Indigenous organizations can also play a critical role. These types of partnerships can include things like sharing resources or space, co-planning, or providing community support for students.

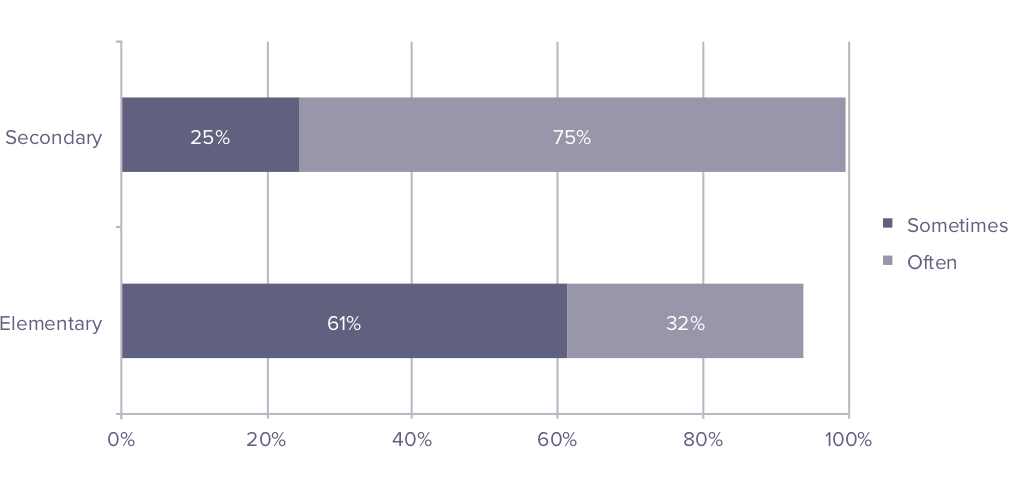

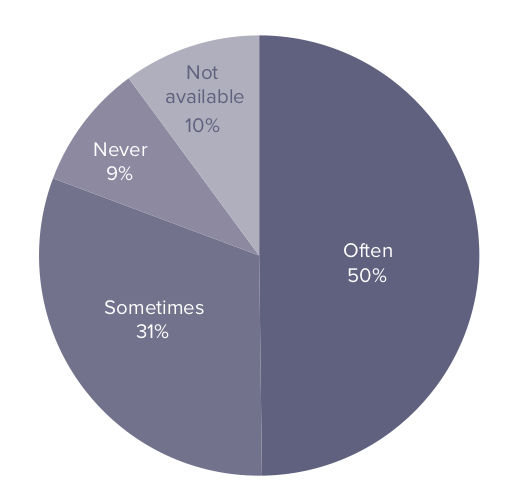

In 2018:

- 3% of elementary schools report they “often” connect or work with Indigenous organizations, compared to 14% of secondary schools.

- 53% of elementary, and 65% of secondary schools report that they “sometimes” connect or work together.

- 90% of elementary and 79% of secondary schools report that Indigenous organizations were “fairly” or “very” accessible to them.

Indigenous languages and Indigenous Studies

Provincial data show considerable growth in the number of students enrolled in Indigenous language programs – from 4,302 students in 2006/07 to 7,795 students in 2015/16. Over the same time period, the number of students enrolled in Indigenous Studies9 courses has skyrocketed, from 1,134 course enrolments to 22,195 (Ontario, 2018b, p. 27). These courses are now offered in 56% of secondary schools across the province.

Funding for both Indigenous language programs and Indigenous Studies is based on an average class size of 12 students, to allow the classes to exist even when enrolment is low. Funding is provided according to demand, and, in the case of Indigenous Studies, funding has grown from $1.4 million in 2007/08 (Ontario, 2007a, p. 45) to a projected $33.5 million for 2018/19 (Ontario, 2018a, p. 54).

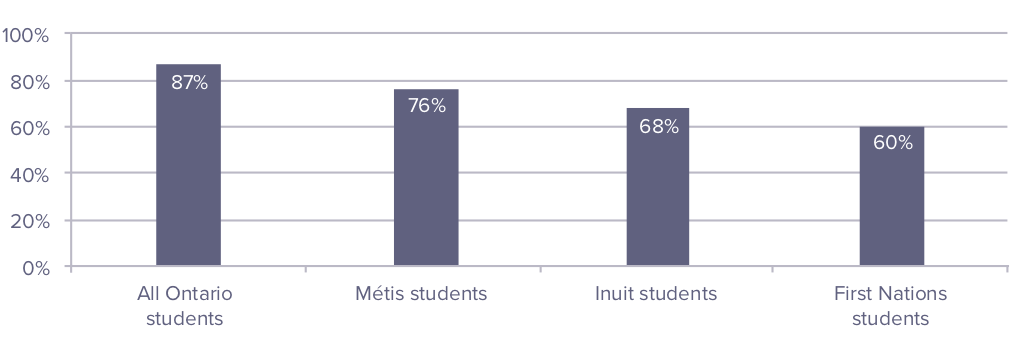

Figure 5.4 Graduation rates for students after five years of secondary school

Time for a broader strategy on outcomes

Ten years ago, the province committed to closing the achievement gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students by 2016. Unfortunately, the gap persists, and improvements on test scores in literacy and numeracy have been marginal.

This year, for the first time, the province reported on graduation rates: among students who started high school in 2011/12, the graduation rate for First Nations students is 27 percentage points below the Ontario average (Ontario, 2018b, p. 70; see Figure 5.4).

In 2018, the Ministry of Education committed to renewing the framework for Indigenous education (Ontario, 2018b, p. 79) to include a broader base of partnerships and support for schools across the province.

Recommendations

Many Indigenous organizations have pushed for a broader definition and different measures of educational success—to include a more holistic vision for education (e.g. Toulouse, 2016). In order to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students in terms of overall success in schools, there needs to be adequate and culturally relevant supports available to Indigenous students, their families, and their communities, as well as a fundamental shift in the definition of success to one that includes strong academic performance, but goes well beyond it.

In 2014, the Ministry of Education committed to work with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit partners and key education stakeholders to “explore and identify additional indicators of student achievement…well-being and self-esteem.”

People for Education recommends that the province:

-

Act on its 2014 commitment and work with Indigenous leaders and scholars to establish a new set of relevant indicators of student success that are more congruent with the interests, needs, and motivation of Indigenous communities, and vital for all students’ success in school and life.

-

Continue to support the Education Equity Secretariat in collecting data about self-identified Indigenous staff and students in school boards across the province (Ontario, 2017e).

8 Comment from an elementary school in Kawartha Pine Ridge DSB

9 Since we released the survey, the name of Native Studies has been changed to Indigenous Studies.

In 2018:

-

46% of elementary schools report having a specialist music teacher, either full- or part-time, up from 41% last year.

-

98% of secondary schools offer a senior (grades 11/12) Visual Arts class, 92% offer a senior Music class, 86% offer a senior Drama class, and 32% offer a senior Dance class.

-

Elementary schools with higher proportion of parents who have graduated from university are twice as likely to have a specialist music teacher as schools with lower proportions of university-educated parents.

-

School budgets for the arts range from less than $500 to $100,000.

It is hard to understate the benefit derived from an education in the arts. Extensive research on the impact of arts education shows that it supports students’ development in areas ranging from improved spatial reasoning (Hetland & Winner, 2001) to a deepened motivation for learning (Deasy, 2002). Most significantly, arts education has the potential to enrich students’ creativity and social development (Hunter, 2005). These two qualities are included in the Ministry of Education’s 21st Century Competencies (Government of Ontario, 2015), and make up two of five key learning domains identified in People for Education’s Measuring What Matters initiative (Shanker, 2014; Upitis, 2014; People for Education, 2018a).

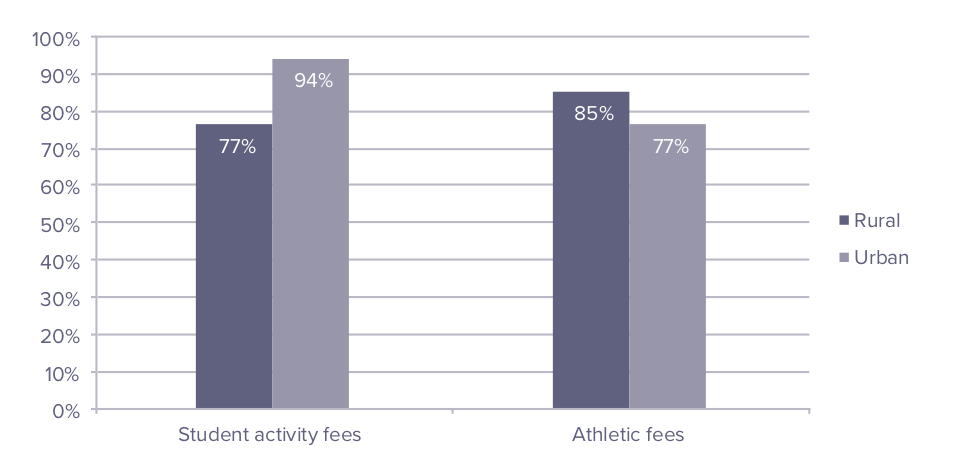

Despite the widely recognized importance of arts education, equitable access to arts programs and resources is an ongoing challenge in Ontario. While some schools offer many extracurricular arts activities, students in small and rural schools, in schools with higher levels of poverty, and in schools with lower levels of parental education, are less likely to have access to learning opportunities in the arts.

Arts funding and school budgets

Until recently, there has been no provincial funding dedicated to the arts, it has been up to school boards to determine how to fund arts education. In some cases, boards allocate money for specific arts initiatives or instructional priorities. For example, some boards provide instrumental music for all students in grades 7 and 8, and will therefore provide some funding to schools for instruments. Other boards provide an instructional budget based on the amount of full-time equivalent (FTE) music specialists there are at each school.

In addition to board funding, schools can fundraise for things like arts excursions, visiting artists, or musical instruments. Together, the funds raised by the school and allocated by the board make up each school’s arts budget for the year.

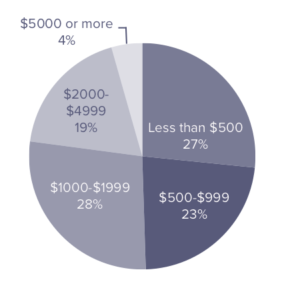

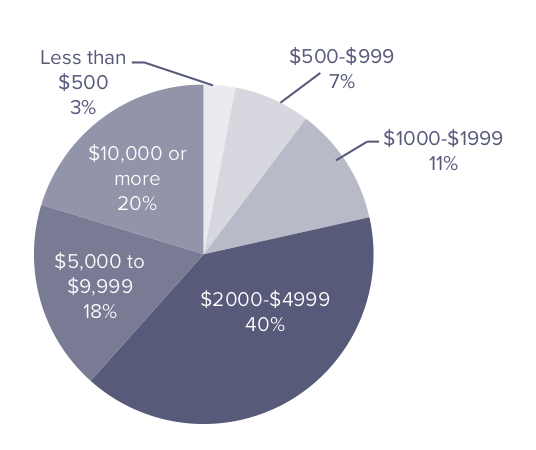

In 2018, we asked elementary and secondary schools about their arts budget. Among elementary schools, these budgets range from under $500 to as high as $20,000 (see Figure 6.1). At the secondary level, arts budgets can reach as high as $100,000 (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.1Percentage of elementary schools whose art budget is… |

Figure 6.2Percentage of secondary schools whose art budget is… |

|

|

Arts budgets: Size matters

Both the survey data and principals’ comments illustrate the impact of school budgets on access to resources and learning opportunities in the arts. One principal commented that “many instruments sit broken until budgetary bottom lines are determined closer to the end of the year. Even then, not all instruments can be repaired because there is not enough money.”10 Another noted that it is “very difficult to keep up with maintenance and replacement costs”11 associated with their instruments.

[Challenges with arts education:] lack of budget to buy musical instruments.

Elementary school, Conseil scolaire de district catholique de l’Est ontarien12

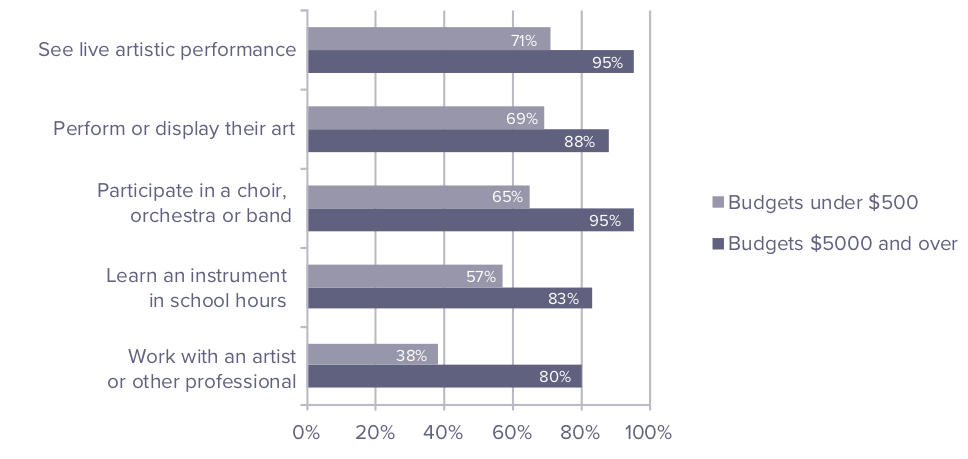

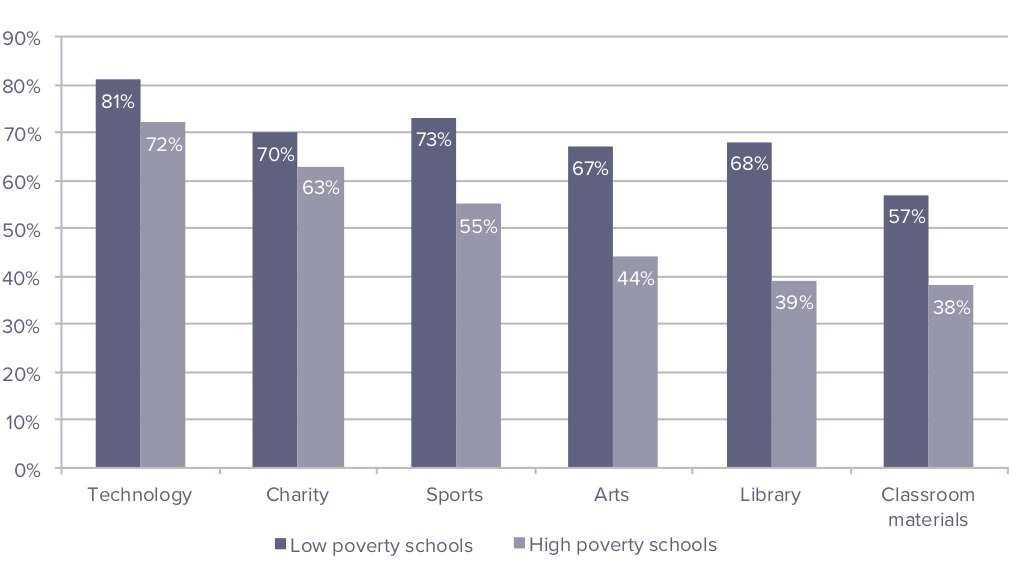

To understand the impact of arts budgets on students’ opportunities to participate in arts enrichment, we examined the difference between elementary schools with the highest (over $5000) and lowest (under $500) budgets. Figure 6.3 shows that the size of a school’s arts budget has a significant impact on learning opportunities for elementary students.

In elementary schools, the arts budget also appears to be connected with the availability of arts programming space. Elementary schools with an arts budget of $5000 or greater have, on average, three times as many types of specialty arts rooms as those with arts budgets under $500.

Figure 6.3 Impact of arts budgets on students’ access to arts enrichment

Secondary schools with budgets of $2000 or higher are more likely to provide arts-related opportunities than those with budgets under $2000. Secondary schools with budgets of $2000 or higher are:

- 11% more likely to be able to display their art

- 15% more likely to see live artistic performances

- 33% more likely to learn an instrument in school hours

- 47% more likely to participate in a choir, orchestra, or band

- 63% more likely to work with an artist or professional from outside the school

Much of our arts is funded through our school council, who have prioritized the arts at this school.

Elementary school, Toronto DSB

The impact of fundraising

There is a clear link between the amount schools fundraise and the size of their arts budgets. At the secondary level, schools that report fundraising for the arts are 22% more likely to report an arts budget of $5000 or more. At the elementary level, this effect is even more pronounced. Elementary schools who report fundraising for the arts are twice as likely to report a budget of $5000 or more. When the top and bottom 10% of fundraising elementary schools are compared, the gap widens further, regardless of whether they reported raising money for the arts. The top fundraising elementary schools are almost three times more likely to have an arts budget of $5000 or more.

The impact of demographic factors

This year, we used information from Statistics Canada and Ontario’s Ministry of Education to examine the relationship between students’ family background and a range of resources and programs in schools. We compared the top and bottom 25% of our elementary school sample in two areas: the proportion of families under the Low-Income Measure, and the proportion of students with at least one parent who has graduated from university. For the sake of comparison, we refer to these as high and low poverty schools, and high and low parental education schools.

Low poverty schools are more likely to raise more money per school, more money per student, and more money specifically for the arts, as compared to high poverty schools. Schools with high parental education were 10 times more likely to have an arts budget of $5000 or more, as compared to schools with low parental education.

Individual educators are required to integrate the arts in their classroom instruction, and often they do not have specialized training; therefore, these areas may not receive the attention necessary.

Elementary school, Sudbury Catholic DSB

Specialist teachers

Ontario’s arts curriculum covers everything from drama to visual arts, music and dance. It is very detailed, and can pose a challenge for classroom teachers—particularly in elementary schools—if they do not have additional training.

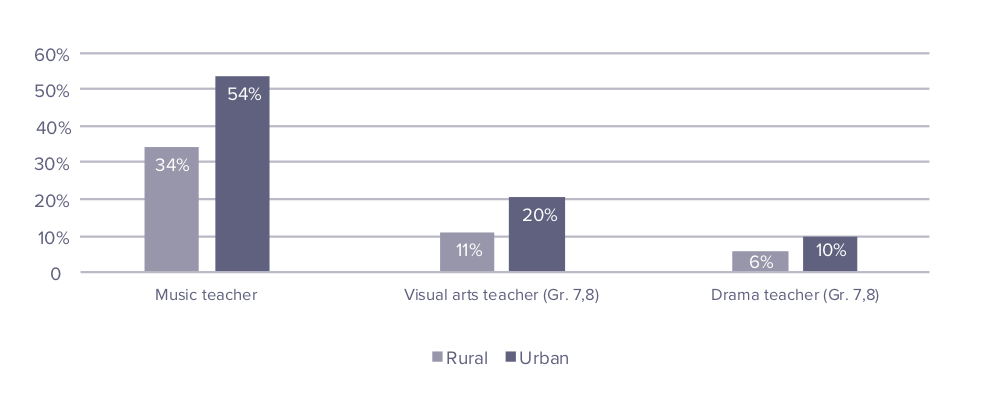

On this year’s survey, many principals commented that their schools struggle with a “lack of specialists” to teach the arts—a concern that is supported by the survey data. In 2018, only 46% of elementary schools report having a music teacher, either full- or part-time. While this is an improvement over the 41% of schools reporting music teachers last year, it is still well below the 58% of schools reporting music teachers 20 years ago. Only 16% of elementary schools with grades 7 and 8 report having a specialist visual arts teacher, and just 8% of elementary schools with grades 7 and 8 have access to a specialist drama teacher.

Access to specialist teachers—the impact of school size

School boards must provide teachers with preparation time, and in elementary schools, that preparation time is usually covered by specialist teachers. Schools with more students have more teachers, which generates more preparation time. As a result, larger schools can hire more specialist teachers to cover that prep time. In this year’s survey, elementary schools with a full-time music teacher average 59% more students than those without a specialist.

This year’s survey results illustrate the impact of funding for preparation time on access to specialist teachers. As funding for preparation time has increased from 2016/17 to 2017/18 (Ontario, 2016b; Ontario, 2017a), we are seeing an increase in the overall percentage of elementary schools reporting a music teacher, from 41% in 2017 to 46% in 2018.

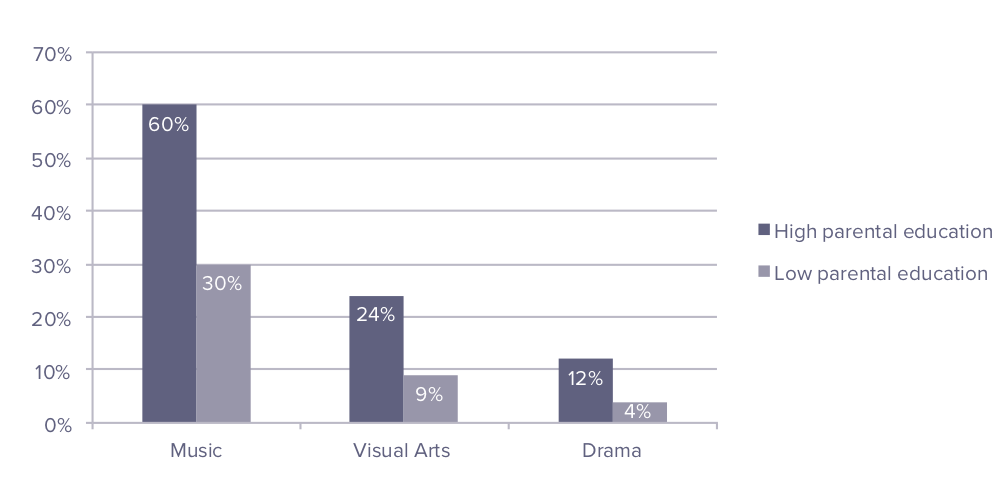

Figure 6.4 Parental education and access to arts in school

Access to specialist teachers—the impact of parental education

This year’s survey reveals that elementary schools with high parental education are twice as likely to have a music teacher (60% of high parental education schools vs. 30% of low parental education schools), and three times as likely to have a full-time music teacher, as those with low parental education. These differences hold even when the data is controlled for region (rural vs. urban) and school size.

This pattern extends beyond music. High parental education schools with grades 7 and 8 are two and a half times more likely to have a visual arts teacher than schools with low parental education, and three times more likely to have a drama teacher (see Figure 6.4).

The space will be lost next year as the school board offers the space to provide daycare at the school.13

Elementary school, Conseil des écoles catholique du Centre-Est

Is there room in schools for the arts?

Learning music, drama, dance, and visual arts requires space—space for instruments and supplies, space for working with different visual arts media, and space to move around. In their comments, survey respondents frequently cite a lack of specialized space as a barrier to providing arts programming. Many principals report that there is no available space because their school is “at capacity,” with one principal commenting that they “barely have storage space, let alone additional space for any learning outside of the normal classroom environment.”14

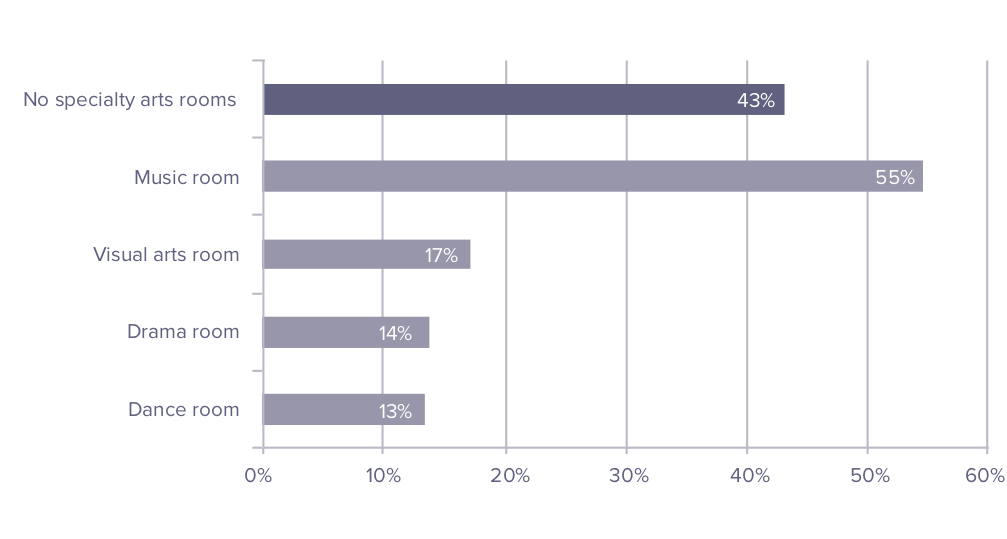

In this year’s survey, 43% of elementary schools report that they have no specialized rooms for the arts (see Figure 6.5).

In 2018:

- 55% of schools have dedicated space for music

- 17% of schools have dedicated space for visual arts

- 14% of schools have dedicated space for drama

- 13% of schools have dedicated space for dance

Virtually all secondary schools (98%) have at least one room for arts instruction, and 83% report three or more specialized arts rooms. Visual arts rooms are the most common, with 96% of secondary schools reporting one. Larger schools are more likely to have more types of specialized rooms.

Figure 6.5 Percentage of elementary schools with specialized art rooms

The urban-rural divide

Schools in rural areas face more challenges than their urban counterparts in providing arts education. According to the survey data, urban elementary schools are three times more likely than rural schools to have budgets of $5000 or more.

Rural schools are also less likely to have specialist drama, visual arts, and music teachers (see Figure 6.6).15 The qualifications held by these educators reveal further disparities:

- 77% of rural elementary schools have music teachers with advanced qualifications, compared to 85% in urban elementary schools.

- 17% of rural elementary schools have drama teachers with advanced qualifications, compared to 52% in urban elementary schools.

This is reflected in the comments on the surveys, with one principal identifying the “recruitment of qualified teachers to come to [their] small rural community”16 as a challenge.

While 37% of elementary schools in urban areas report that they do not have any specialized arts rooms, this rises to 53% of elementary schools in rural areas. This pattern holds true even after accounting for the impact of school size, although the gap is not quite as pronounced in similarly-sized schools.

Our school is a small country school with only 8 classrooms. Our teaching staff allotment doesn’t afford us the opportunity to have specialist teachers.

Elementary school, Lambton Kent DSB

Figure 6.6 Percentage of elementary schools with specialist arts teachers, by region

Equity and the arts

The cost of arts activities and programs outside of the school day make them inaccessible to many families. This year, data from student questionnaires completed as part of the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) assessments, show that overall, 43% of grade three and 39% of grade six students participate in art, music, or drama activities at least once a week when they are not at school.

However, there is a relationship between schools’ arts budgets and the amount they fundraise, and students’ participation in the arts. In schools with lower arts budgets (which are also more likely to have a higher proportion of students with lower family incomes), students are much more likely to say they “never” participate in art, music, or drama activities outside of the school day. This, along with regional disparities in access to specialist teachers and specialized learning spaces, points to worrying inequities in students’ access to arts education.

Recommendations

Arts education builds foundational skills and competencies that have an impact on students’ long-term success. Students’ critical thinking, persistence, social-emotional, collaboration, and communication skills are all developed in arts education. But students’ access to strong arts education is affected by where they live, their parents’ income and education, and their school’s capacity to fundraise.

People for Education recommends that the province:

-

Work with educators and stakeholders to evaluate the costs of arts education, both during and outside the school day.

-

Recognize and fund resources and programs that support learning in the arts.

-

Ensure that core competencies gained through arts education are embedded in the arts curriculum.

10 This comment is from a secondary school in Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB

11 This comment is from an elementary school in Lakehead DSB

12 Translated from French. Original comment: “Manque de budget pour acheter des instruments de musique.”